The History of Arab-Jews Can Change Our Understanding of The World

Historian Avi Shlaim describes the devastating effects that rigid nationalism has on hybrid cultures, such as the Jewish Baghdad of his early childhood.

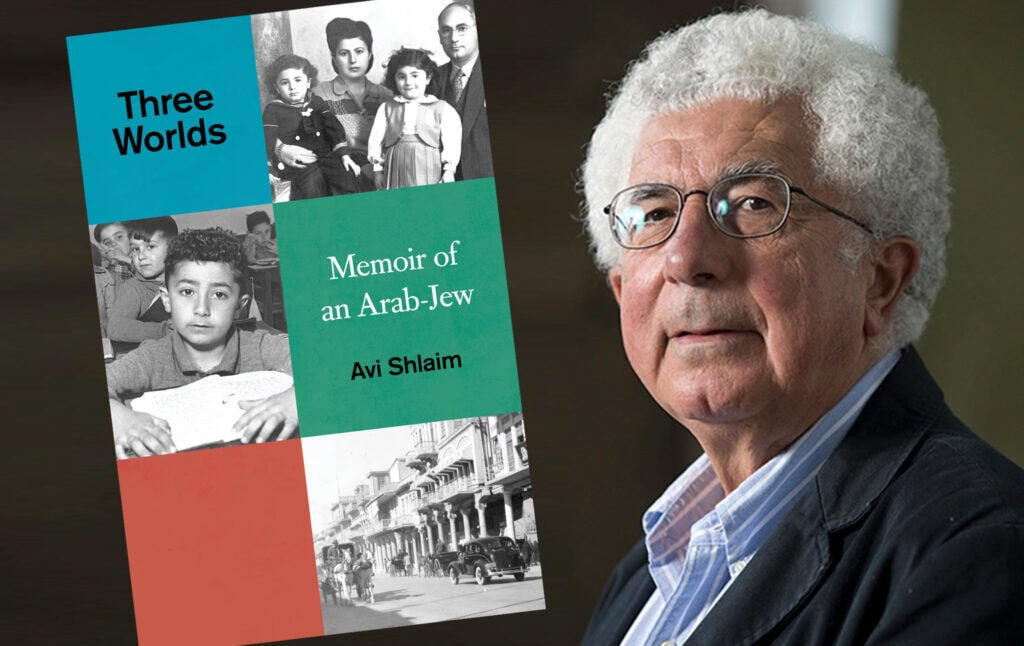

Avi Shlaim is a distinguished historian and Emeritus Professor of International Relations at Oxford University. He is one of the Israeli “New Historians” whose pathbreaking work debunked some of Israel’s most cherished national myths. Now he has written a fascinating memoir, Three Worlds: Memoirs of an Arab-Jew, that challenges conventional understandings of Zionism, the binary categories of “Arabs”/”Jews,” and the very nature of nationalism.

Prof. Shlaim is known as a “British-Israeli” historian, but as his memoir explains, he was actually born into a cultural world that has long since vanished: the Baghdad of the “Arab Jews,” whose culture and language was Arabic but whose faith was Judaism. Shlaim’s memoir tries to recapture this cosmopolitan existence, where Muslims and Jews lived in relative peace side-by-side. For families like Shlaim’s, the birth of the state of Israel was something of a tragedy, because it shattered their world, creating new animus between Iraqi Jews and Iraqi Muslims. Prof. Shlaim’s discussion of the early days of Zionism, and the effects it had on the Jews of Baghdad, shows that Israel’s claim to operate in the interest of the world’s Jewish population is highly questionable. Prof. Shlaim even claims that he has uncovered evidence that the Zionist movement was willing to resort to violence against Jews in Baghdad in order to build the Jewish state. His memoir, despite being tragic in many ways, is ultimately hopeful, because Prof. Shlaim still believes in the possibility of a country where ethno-religious binaries break down and different peoples can live side by side in a hybrid culture.

Nathan J. Robinson

I had always read, in descriptions and bios, that you are a “British-Israeli” or “Israeli-British” historian, but this is not quite accurate. It leaves out one of the “three worlds” described in your book. Your book is in many ways about a lost world—the original world that you came from. It is about the Jews of Iraq in the era before and immediately after the founding of the state of Israel. And you say that one of the purposes of your memoir is to “recover and reanimate a unique Jewish civilization of the Near East, which was blown away in the first half of the 20th century by the unforgiving winds of nationalism.” Could you begin by introducing us to this first world?

Avi Shlaim

Thank you. The three worlds of the title are: Baghdad, where I lived up to the age of five—I was born in 1945 to a Jewish family; the second world is Ramat Gan, a town in Israel near Tel Aviv, where I went to school from the age of five to 15; and because I didn’t do well at school and was about to be thrown out of high school, my parents sent me to school in London, from the age of 15 to 18. The book ends when I was 18, but there is a very long epilogue that traces the evolution of my views about Israel up to the present day, and today, I’m a supporter of one democratic state with equal rights for all its citizens.

So, to answer your question about the first world, that’s Baghdad, 1945 to 1950. That is the most important part of the book. Because this is not a conventional autobiography, it does two things: it’s an autobiography of my early life, but it’s also a history of my family, as well as a history of the Jewish community in Iraq in the first half of the 20th century. My wife read the chapters as I wrote them one by one. She got to chapter five and said, “I’m very worried because you haven’t been born yet.” I said, “that is precisely the point.” The book is not just about me. It’s about a much bigger subject: the Jews of Iraq. And that was, as I said in the part that you quoted, a unique Jewish civilization of the Near East.

The Iraqi Jewish community was the most ancient Jewish community in the world. It had been in Mesopotamia since the days of Babylon exile in the sixth century BC. And of all the Jewish communities in the Middle East, the Iraqi Jewish community was the wealthiest, the most prosperous, the most successful, and the best integrated Jewish community in the Middle East. So, in many ways, Iraq was a model of Muslim-Jewish coexistence and the Zionist narrative is very dismissive of this civilization. It’s as if the history of the Jews of the Middle East only started once it came to Israel.

I try to paint a detailed picture of our lifestyle, culture, and civilization. The main point that I make in this part of the book is that we were Arab-Jews: we spoke Arabic at home, our culture was our culture, our social mores and customs were Arab. My parents’ music was a nice blend of Arabic and Jewish music. I make a pitch for a really unique world that has faded away.

Robinson

When you start to read about this lost world, I think to many of us who have developed our understanding of the Middle East through these fixed mental categories, this idea of “Arab Jews” comes as a surprise. It’s almost surprising when you start to talk in your book about Jews who have Arab names. You explain that this is in part because the construction of nationalism over the course of the history of the state of Israel has wiped away this hybrid culture.

It wasn’t just that you had a separate Jewish community living in Iraq that was very distinctively, and obviously, Jewish. There was a lot of crossover and hybridity, and it’s rather extraordinary. It isn’t something that’s easy even to think about today.

Shlaim

This is the key point: pluralism. Iraq was a pluralistic country, and it had many minorities: Christians, Assyrians, Chaldean Catholics, Turkomans, and Jews. The Jews were one minority among many. They did not stand out. They were not like the Jews in Europe, who were “the other.” And in Europe, Europe had what was called a “Jewish problem.” Iraq didn’t have a “Jewish problem,” it just had a range of minorities who, by and large, got on quite well. There were issues, but Muslims, Christians, and Jews and all the others got on quite well. The Jews were part of that.

In Iraq—in Baghdad—the Jews didn’t live in ghettos, they lived everywhere. And in Iraq, the Jews belonged to all social classes. We were an upper middle class, prosperous family, but there was quite a large working class and class of poor Jews. So, the Jews weren’t distinct or exclusive in any way; they were part and parcel of Iraqi society. King Faisal I, after the British created the kingdom of Iraq after the First World War, had it as his mission to forge one nation from all these different groups, and particularly embraced the Jews as a positive element in the Iraqi society. In the 1920s, it was said the Jews had an “Iraqi orientation,” which meant playing a full part in nation building in the building of the new Iraq. So, we weren’t outsiders, we weren’t foreigners, we weren’t intruders. We are part and parcel of Iraqi society.

Robinson

I just want to dwell on this fact of shared culture. There was a religious difference between Jews and Muslims, but there was a shared culture to the point where when your family eventually arrived in Israel, you obviously were bringing Arab culture. This was your culture.

Shlaim

This was our culture. We were Arab Jews, but this culture was not welcomed in Israel at all. Israel was a new society, with a Zionist ideology of creating a new Jew who was strong and self-reliant. Israel was a reaction against the diaspora, and also we arrived in Israel after the first Arab-Israeli war of 1948. The Iraqi army had fought in Palestine in 1948. There was a backlash against the Jews in all the Arab lands, including Iraq, in the aftermath of the Arab defeat in 1948.

So, by the time we arrived in Israel in the early 1950s, the Arabs were the enemy, and Arabic was considered the language of the enemy. I was hugely embarrassed when my father spoke to me in Arabic in the street in front of my friends because I internalized the values of my new society. Everything Arab was considered hostile, foreign, alien, and primitive. What I didn’t understand at the time is that we don’t choose our identity for ourselves. I had a clear identity when I arrived in Israel at age five: I was an Arab Jew. But our identities aren’t informed just by us or by forces that are benign, but sometimes by other forces that are not so benign, as in this case, Zionism. Zionism is about erasing my Arab Jewish identity and giving me a new identity as a new Israeli, with which I’ve never felt really comfortable with.

Robinson

It’s extraordinary. People changed their names, and obviously, they had to stop speaking their language. There is a scene in the book where you were, I think, wearing jewelry in school, which would have been a normal thing in Iraq, but it was a kind of shameful or alien thing that was outside the kind of cultural practices that they were trying to make sure everyone conformed to in Israel.

Shlaim

Yes, there was definitely a new culture in Israel, and it was a pioneering culture of nation building. For my Bar Mitzvah, I was given a gold ring and a chain with a Star of David. And my teacher, who was a Holocaust survivor from Germany, didn’t like this jewelry, and he told me in front of the class to take it off. It was a very humiliating experience. That’s a good example of the clash of cultures, of the culture we brought with us from Iraq and the new culture in Israel. And, as you mentioned, many Jews, not just from the Middle East, but from everywhere in the world, were made to change their names on arrival in Israel.

Robinson

Yes, there’s no respect at all for the original culture. One of the arguments that you make throughout the book is that Zionism was presented as this force for Jewish strength and the preservation of Jewish culture, and that there’s only a very particular kind of Jewish culture. But it was, in fact, very destructive of the multiplicity of Jewish cultures that had flourished around the world, like the hybrid Arab Jewish culture that you grew up in.

Shlaim

That’s right. Israel had a very strong commitment to the gathering of the exiles, creating a new Jewish state, and doing away with the habits of the exile. But it’s not only in language and social customs that this manifests in itself. The Zionism of the state of Israel also manifests itself in education. At school, I learned a lot about Jewish history in Europe and about the Holocaust, but I was never told anything about the history of the Jews in the Arab lands. The American Jewish historian Salo Baron coined the phrase the “lachrymose version of Jewish history.” That is to say, Jewish history is a never-ending chain of suffering, victimhood, persecution, discrimination, and violence culminating in the Holocaust. I’m prepared for argument’s sake to concede that the lachrymose version of Jewish history fits the history of the Jews in Europe, but I deny that it fits the history of the Jews in the Middle East.

What happened in Israel was that the Eurocentric version of history—the lachrymose version—was imposed on our history. Our history was erased, and we were regarded as victims of eternal Arab antisemitism. And now, in this book, I’ve requested the right to narrate our own history, which is distinct from European history. I’ve not only requested this right, but in the book I assert my right to write our own history.

Robinson

I think it’s fair to say that your history is inconvenient for the nationalist narrative of the State of Israel. Because if it is true that there have long been examples of relatively peaceful Arab-Jewish coexistence and cultural hybridity, the argument for Zionism is not quite as strong.

Shlaim

The perspective of my book, and my general political perspective, is inconvenient for Zionism because it challenges it. My academic discipline is international relations, and my main research interest the last 50 years has been the Arab-Israeli conflict. So, I knew who were the main victims of Zionism: the Palestinians. In 1948, there was the Nakba—the “catastrophe.” Three quarters of a million Palestinians were made refugees, and the name Palestine was wiped off the map. What I discovered from when I was writing this book is that there was another category of victims of Zionism who are much less talked about, and that is the Jews of the Arab lands, and this is what my book is about. So it doesn’t fit in with the Zionist master narrative, which says the Jews everywhere in the Middle East—everywhere in the Arab and Islamic world—were victims of perennial pervasive antisemitism, and it’s because of this antisemitism that they were forced to come to Israel, and the infant state of Israel nobly provided them with the safe haven. It’s this master Zionist narrative that I challenge throughout my book.

Robinson

To the extent that it was true that life became untenable for Jewish families in Baghdad like yours, that was in many ways a consequence of the founding of the state of Israel, which you argue in this book was very destructive for Jewish-Muslim relations outside of Israel itself.

Shlaim

This is a paradox about Zionism. Zionism’s ultimate aim was to create an independent Jewish state in Palestine and a safe haven for Jews facing persecution everywhere. But the result of creating the state of Israel, taking over Palestine, and displacing the Palestinians was to create a deep conflict between Israel and its neighbors and, by extension, make life unsafe and uncomfortable for the Jews in the Arab and Islamic world. So that is, indeed, the paradox of Zionism.

Robinson

And as you show in the book, in many ways, the standard of living and the experiences of Arab Jews when they got to Israel was greatly diminished. The story of your father is rather tragic. He was prosperous and successful in Iraq—very well liked, very sociable—and then in Israel, sort of became a broken man.

Shlaim

My father is just one example. There are 125,000 Iraqi Jews who ended up in Israel. The story of my father is particularly sad because he was such a wealthy and successful merchant with such high status in Iraq. He knew many of the ministers—they were clients— and my parents moved in high society. He had to leave Iraq illegally across the border into Iran and then joined us in Israel. He lost most of his wealth. In Israel, he didn’t know Hebrew. He never really got on his feet, was unemployed, and mildly depressed most of the time. So, he never recovered from this upheaval.

But that’s one example. It’s not necessarily typical. Individual experiences of the Jews of Iraq in Israel varied. By and large, the Jews of Iraq did better in Israel than other Jews, like Moroccan Jews. So, individual experiences varied, but there was a collective trauma on arrival in Israel. The Jews from Iraq arrived in Israel en masse with one suitcase and 50 dinars. They lost everything. They arrived in Israel penniless. And when they arrived at the airport, they were sprayed with DDT—with insecticide—like animals. On arrival in the Promised Land, they were sprayed with DDT, and this was a collective trauma for all the Jews. The great majority went into Ma’abarot transit camps, where conditions were very poor—hygiene was poor, and the food was not what they were used to.

It was a very difficult period of transition, having to learn a new language. But what I tried to show in the book is that for the Jewish community as a whole, the experience was like that of a tree being pulled up by the roots.

Robinson

One of the most startling points of the book, which has actually gotten some press coverage, is that the Zionist movement resorted to some pretty ruthless tactics to try and accelerate the departure of Jews from the Middle East. There are really extreme examples, like trying to foster violence in Baghdad or committing violence directly that would terrify the Jewish population into fleeing to Israel.

Shlaim

This is an extreme example of what I said earlier about the paradox of Zionism, of providing a safe haven for Jews, when, in fact, the Zionist movement was responsible for bombs that went off in the streets of Baghdad to frighten the Jews into immigrating to Israel. This is a very controversial aspect of the book. Chapter seven is called “Baghdad Bombshell.” This is something that always interested me since I was a boy in Ramat Gan. All my relatives and the Iraqi Jews were convinced that Israel was behind the bombs that forced them to come to Israel. And whether this was right—true or false—this is what they believed, and fueled the resentment of the new country.

So, I’ve investigated this subject, and believe that I found undeniable evidence that Israel or the Zionist underground was involved in three out of the five bombs that accelerated the exodus from Iraq. Under the Shah, Israel had close covert relations with Iran. There was a Mossad officer named Max Bennett [Meir Max Bineth] in Tehran, and he was a controller of Zionist activists operating in Baghdad, and one of them was named Yusef Basri, and I have evidence that Basri was responsible for three out of the five bombs. He was caught and had a proper trial. Evidence was produced against him and he was condemned to death by hanging. So, I have a Baghdad police report, which names him and details some of his activities. This is incontrovertible proof that the Mossad through Zionist activists in Baghdad were responsible for some of the bombs, not all of them.

Now, some of my critics deny altogether and say it’s a conspiracy theory. Well, I’ve produced hard evidence, a smoking gun, but some critics say this is not the reason that the Jews left; the reason that the Jews left Iraq was because of antisemitism and persecution, not because of the bombs. It’s not part of my argument that the bombs were the main cause for the exodus. I say there are other, more important reasons, like official persecution after the 1948 War, that was the main reason. It was hostility towards the Jews and rising antisemitism. But the fact that Israel was involved in creating conditions of panic, fear, and uncertainty is very significant. And even if not a single Jew left Iraq for Israel because of the bombs, I would still say it’s very significant because it tells us something about the nature of Zionism and its methods.

Robinson

It certainly is an illustration that the story of Zionism as operating in the interests of all Jews worldwide is probably not true. I think that people would most likely not question your evidence, but they might not be able to make sense of it. They might ask, but why? Why would it be the case? Why would those who were trying to, in good faith, produce the Jewish state and gather in the exiles, engage in targeted bombing attacks against Jews to facilitate the growth of the state of Israel? What was the underlying reason there that could justify such a thing?

Shlaim

I think nationalism. Nationalism is a very powerful and negative, divisive force. Patriotism is different: it’s love of your country. But for nationalism, you have to have an enemy, and Israel always had enemies. And it was always nationalistic—never as nationalistic as it is today with the present government. I used to ask my students to assess the relative weight of socialism and nationalism in the making of modern Israel. The answer was that socialism was a force, but nationalism was a much more powerful force and always overrode or triumphed over socialism.

So, the leaders of Israel were single-minded Zionists who were determined to build up the state of Israel by any means, fair or foul. What I illustrate is one aspect of the ruthlessness, and planting the bombs in Baghdad wasn’t a one-off thing. It was part of a pattern. In 1954, there was the famous Lavon Affair, when a group of Egyptian Jews were caught planting bombs in public places in order to create bad blood between the Nasser regime and the West. The whole group was captured and arrested, including the Mossad officer controller Max Bennett, the same man who had orchestrated the bombings—the false flag operation—in Baghdad.

So, there is a pattern of ruthless Zionism and its behavior, which is not at all calculated to promote the interests of the local Jews, but on the contrary, it recruited local Jews, turned them into spies and saboteurs, and made them turn to terrorism against other Jews. That created real tensions and hostility, both in Iraq and in Egypt, towards the Jews in the aftermath of the Lavon Affair.

Robinson

You’ve said that your contentions are controversial. But interestingly, I was just reading a new memoir by one of the leading Zionists in the United States, Martin Peretz, who owned the New Republic for many years. I was interested to see that at one point he comments on this in his memoir. He writes, “Zionists were accused of bombing Jewish cafés in Baghdad as a trick to accelerate the exodus, and this may be true.” So even here, I expected that sentence to end with him saying, “and this is an outrageous slander against Zionism,” but he instead says it may be true.

Shlaim

I can say is that it is true. In the past, there were only rumors which were denied forcefully by Israel. There were two commissions of inquiry, which both gave Israel a clean bill of health and said there was no Israeli involvement. In my book, I present the evidence that I’ve been able to gather, which shows conclusively that Israel was involved in these operations to force the Jews to leave Iraq and to end up in Israel.

And I’ll say one other thing about this. I looked at the motives of the Israeli policymakers and I looked for statements to justify their actions, and they said that, rather than working for the good of the Jews wherever they might be, the actions pointed in a different direction. The actions pointed to a single-minded concern with Israeli national interest, rather than the interests of the Jewish communities. In fact, Zionism was never interested in the Jews of the Middle East, until the Holocaust. The Holocaust removed the main reservoir of population for the Jewish state to be. It was only after the Holocaust that the Zionist leaders began to look for Jews wherever they could find them, including the Middle East. They looked down on those Jews. They thought that they were human material of an inferior kind. But now, the overriding priority for the state of Israel after 1948 was immigration—increasing the population. That’s when they became seriously interested in the Jews of the Arab and Islamic world.

Robinson

That helps to explain what seems somewhat paradoxical, which is that despite wanting people, like the members of your family, to leave Baghdad and go to Israel, they didn’t seem to want you when you got there. Or they seem to make you feel inferior and feel like you didn’t belong and like you shouldn’t be there in the first place.

Shlaim

We certainly weren’t made welcome. I, personally, didn’t encounter overt discrimination. But it was in the air that everything European was superior, and everything Eastern was alien and backward. I internalized the values of Israeli society, and as a result, I had a chip on my shoulder which defined my relationship with the state of Israel. But looking at the Jews from all over the Arab world, particularly the Moroccan Jews, they felt that they weren’t made welcome in Israel. They were looked down upon, they were humiliated, and they never got a fair shake in Israel. My mother used to go on about the wonderful Muslim friends that we had in Baghdad, and one day I asked, did we have any Zionist friends? And she looked at me as if it were a very strange question, and she said to me, no, Zionism is an Ashkenazi thing—it has nothing to do with us.

Robinson

You say that you didn’t encounter overt discrimination as a child, but it seems like the condition of that was suppressing your differences. Certainly, your differences from the Ashkenazi Jews were very palpable and affected you in many ways. It gave you an inferiority complex, and teachers seem to look down on you or single you out. Whether it was overt explicit spoken discrimination or not, there certainly seemed to be a very strong effort to make sure that you either conformed or would be alienated.

Shlaim

I did feel alienated, but I was a schoolboy, so I didn’t understand the dynamics. I saw a state of Israel going around me at a phenomenal pace. It’s a very dynamic society, a lot was happening. But I also felt subjectively that the state of Israel was an Ashkenazi trick, and I didn’t fully understand it and wasn’t part of it. So, I did feel alienated. But, I was very confused when I was a school kid and I didn’t assert my Iraqi identity. I tried to erase it. It’s only today, at 77 years old, that I can understand my original identity as an Arab Jew.

Now, I’m proud of being an Arab, and very proud of my heritage. I also understand that the fact that I had lived in an Arab country was, in some ways, an advantage, because unlike other Israelis who grew up in Israel and saw the Arabs is a monolithic enemy, I’ve lived with Arabs. For us, for my family, Muslim Jewish coexistence wasn’t an abstract concept. It was a daily reality. We lived this. So the fact that I grew up in an Arab country enabled me to think of Arabs later on in life not just as an enemy, but as a proud and sensitive people. It gave me a different perspective on Arab-Israeli relations as well. So, there are some advantages to being an Arab Jew in Israel in the 1950s.

Robinson

I’d like to conclude here with some of the implications of the story that you tell here for our present day, thinking about the Israel-Palestine conflict. You are pretty openly anti-Zionist. I think you’ve said Zionism is inherently racist. The story that you tell here is of Zionism and the building of a Jewish state in Palestine as, essentially, a tragic story—a story that was ultimately not good for, obviously, the Palestinians expelled during the Nakba, but was also not good for those Jewish communities outside of Israel in the Middle East that were ultimately destroyed. A whole world was sort of wiped away. What would you like us to take away from this story as we think about how to have peaceful coexistence in the former state of Palestine, the current state of Israel?

Shlaim

The main takeaway from the story that I tell in the book is that the Zionist claim that Arabs and Israelis are doomed to antagonism and hostility—that the conflict is preordained that Jews and Arabs cannot live in harmony and in peace—is false. The experience of my family contradicts it and tells a different story. It points to the possibility of coexistence, cooperation, and harmony between Muslims and Jews. The fact that we experienced that, and recalling of that world that has faded away, enables me to think of a better future for the region. Because look at the Middle East today: it’s a dismal wreck. Look at Israel today: it has such a right wing, xenophobic, overtly racist government. And look at the consequences of that: the escalation of violence—the settler violence—against Palestinians. So, the situation today is absolutely abysmal. I’d like to think of a better world, and recalling the past enables me to think of a better pattern of relations of one democratic state, from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea, with equal rights for all its citizens, regardless of religion and ethnicity.

Robinson

You are not an advocate of a separate Jewish state and Palestinian state, presumably, because you feel like these don’t have to be two fixed different peoples, with no overlap between the Israelis and Palestinians. As you point out, through this recapturing of the world of the Arab Jews, nationalism creates these bizarre artificial boundaries between people in the real world. There could be so much overlap and hybridity.

Shlaim

I’ve always believed in a one-state solution. Most of my life, I supported a two-state solution: an independent Palestinian state on the West Bank and Gaza with a capital city in East Jerusalem. But Israel has completely destroyed that possibility, and it’s become fashionable to say that the two-state solution is dead. I would argue that the two-state solution was never born. No Israeli government has offered an independent Palestinian state that would be remotely acceptable to even moderate Palestinians, and no American government has ever pushed Israel into a settlement. So, a two-state solution is just an empty slogan.

The reality is that there is one regime between the river and the sea, and it’s dominated by Israel. It’s an apartheid regime, and it’s a Jewish supremacist regime. It’s this that I object to, but I don’t have a problem with Israel’s legitimacy within its original pre-1967 borders. What I object to is the Zionist colonial project beyond the green line with the settlements and the occupation of the West Bank. So, I’ve always wanted Israel to end the occupation, and the two-state solution to resolve the conflict. But Israel eliminated that option. The only democratic solution is the one-state solution. So, I wouldn’t so much describe myself as an anti-Zionist as a post-Zionist, because by 1967, there was a viable, secure Jewish state, and Zionism was a success story. It’s achieved its aims. It’s the occupation that has changed everything and has undermined the foundations of Israeli democracy.

The Six Day War was a landmark in my own personal history because I served in the Israeli army in 1964 to 1966. I served proudly and loyally because in my time, the IDF was true to its name: it was the Israel Defense Forces. But after the occupation, the nature of the army was changed from being a defense force to the brutal police force of a brutal colonial power. That’s why I disapprove. That’s why I’m opposed. I’m critical of the consequences of Zionism because it was pushed to extremes with the occupation.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.