A Dead Man’s Plea for The Rights of Prisoners

On the life of Shawn R. Griffith, and the extraordinary book he produced during his precious few years of freedom.

During a recent trip to my hometown of Sarasota, I stopped by our local YMCA to exercise. Outside the Y is a Little Free Library, and even on the rare occasions where I am back in town and visit the Y, I don’t usually look in the box, because most of the time it’s full of chewed-up Dean Koontz novels and books about Jesus. This time, for whatever reason, I checked it, and so came across a copy of a book that I don’t think I would ever have discovered in my lifetime if I hadn’t looked in that particular box on that particular day.

The book is called Facing the U.S. Prison Problem: 2.3 Million Strong—An Ex-Con’s View of the Mistakes and the Solutions, and it is written by a man named Shawn R. Griffith. The reason I don’t think I’d ever have come across it otherwise is that it was self-published in Sarasota and is out of print, which means there are only a few copies out there in the world and most of them are probably in Sarasota itself. (You can’t find one on Amazon, for instance. There is a single copy available on AbeBooks.)

I’ve read a lot of books about prisons, and many of them recite the same depressing facts. I’ve written before (in my first-ever print article for Current Affairs) about how challenging it can be to make mass incarceration “interesting.” Most books on prison reform, even when good, lack the power to surprise me.

But Shawn Griffith’s book is fascinating, and so is the story behind it.

It’s a dense tome, laden with statistics about the prison system. Griffith wrote it when he was 41 years old, and had just been released after serving 20 years in prison. It’s a passionate plea to Americans to care about the situation of the millions of people we imprison. Perhaps self-conscious about his lack of a formal academic background, Griffith wrote a book that is almost excessively well-researched, with hundreds of citations to court cases, government reports, news articles, statutes, and journals. But at its heart it advances a straightforward argument: not only is it unconscionable to keep so many people in prison, but it’s entirely counterproductive. Griffith, drawing on both scholarly research and his decades of personal observation (he estimates that during his time inside he came into contact with 30,000 prisoners and 5,000 corrections workers), makes a point that needs to be much more widely understood. He says that our prison system is causing, not solving, crime. Because we are committed to showing “criminals” no mercy and not “coddling” them, we are unwilling to give those convicted of crimes the tools they need to flourish in life. “Tough on crime” policies actually give us crime.

Griffith is not making a novel argument. But that’s part of what gives his book its strength. Professional academics often feel the need to try to say something nobody has ever said before and don’t want to say anything simple for fear of being thought facile and unoriginal. Griffith isn’t limited by this, so his book sets out to make a simple point as persuasively as possible. He wants to show us that our prison system is an absurdity and encourage us to change it.

The book also draws persuasive power from the fact that Griffith comes across not as an abolitionist radical, but almost conservative. He uses framings that might make leftists uncomfortable, constantly harping on how much the “taxpayer” is losing through our failure to rehabilitate prisoners and lamenting the way warehousing people encourages “laziness.” He is very insistent that he is not “attempt[ing] to shift the blame for crime onto someone other than the criminal.” He says at one point that rich Americans get rich through hard work, and I rolled my eyes.

I say this gives the book power, though, because Griffith comes across as being about as “moderate” as you can be while nevertheless offering a devastating indictment of the American prison system. Because his writing voice is that of a “patriot” who believes in nothing more radical than good government, he makes it seems as if you don’t have to be a leftist to be horrified by the cruel (and counterproductive) way that we treat those convicted of crimes.

After I’d looked through Griffith’s book, I thought I’d get in touch with him and try to book him on the Current Affairs podcast, where I interview authors every week. But I quickly found out this was impossible: Griffith had taken his own life just a short time after the book was published. It was then that I took a closer look at the preface and found the following:

By the time many people read this after it has been published for five or ten years, unless I receive some very good medical treatment, there is a good chance that I will be deceased. I do not feel another 20 years of life left within me. The system literally sucked the life out of me through stress, inadequate medical care, substandard nutrition, and callous treatment. It damaged my heart (for which I now take medication), my brain, and my nervous system. I have been stabbed, beaten, maced, confined, robbed, threatened, bacterially infected, and medically neglected so many times that I am worn out. I am exerting every bit of energy I can muster to hopefully make a difference with the insight I have gained over a long, difficult, but spiritually enlightening journey.

Sure enough, I read the book ten years after he wrote it, by which time he was gone. The haunting preface made me look at the book in a different light: not just as a comprehensive look at prisons by a guy who knew them well, but a volume that he put his whole self into, trying desperately to get the attention of the public, during the brief two-year period of freedom between his release and his death. I consider it my job to tell you a little of what Griffith has told me.

We are doing it all wrong, Griffith argues. When people commit crimes, we should figure out what it would take to make sure they don’t inflict harm again. That involves treating addictions, getting people set up with jobs and housing, educating them, and strengthening their family and community ties. Instead, we do none of that. Griffith writes mostly about his home state of Florida, which he says has “62 major prisons, 77 work camps and community-based facilities, 161 probation offices, about 28,000 correctional employees, and a 2010 operating budget just over $2.2 billion.” (According to the state, it now has 143 total facilities and its budget has increased to $2.7 billion.) These prisons, he says, squander money by simply warehousing people, giving them the opportunity to learn almost nothing except how to commit more crimes. (A “Bachelors in Burglary” is the only degree available, he writes.)

Griffith is scathing about what he calls “slave labor and lazy labor.” Slave labor consists of making prisoners toil in brutal conditions for no money. Lazy labor (not the term I would have used, but it’s his) is when prisons give inmates useless, boring make-work jobs that don’t achieve anything or build any skills. These “jobs,” Griffith says, can be just as damaging for the inmate as the slave labor. He writes of teams of inmates given rakes and told to rake an open yard “without a single tree or shrub”:

“Hundreds of inmates stood around raking lines in the dusty red clay, six hours a day, in the same small number of square feet, over and over, day after day. Some of those men have life sentences and will continue raking those lines in the dirt into 2014 and beyond… The drudgery of this will eventually drive many prisoners to nervous breakdowns, as it has for many others.”

He cites another example of a prisoner whose job as the “prison librarian” was simply to sit and check off the names of people as they came in to use the library. These kinds of bullshit jobs, Griffith says, are dehumanizing and are “weakening prisoners’ chances for successful reintegration into society.” They are “training prisoners to fail” in the outside world.

But this is what we have built. Instead of preparing people for success, “the human warehouses were gutted of almost everything except rows of razor wire, rows of bunk beds, and rows of prisoners lying in them.” There is little education, Griffith says, because prison officials believe that “an educated prisoner is a dangerous prisoner,” and “educated prisoners are more capable of challenging abusive practices in non-violent ways that society can understand.”

Much of the “education” and “job training” that Griffith saw in Florida prisons, he says, was a “hoax” or “fraud.” For instance, he says that early during his time in prison, he decided to enroll in an auto mechanics class:

When I entered the classroom, I was really excited. I had been spinning my wheels on the street, going nowhere in life. At nineteen years of age, I was hopeful that maybe I could learn some skills at something I enjoyed, something that could give me traction and get me moving in the right direction. After only a few hours of being in the class, I was disappointed. There were about twenty other teens and a few men in their early twenties sitting around. Some were telling stories about criminal escapades; some were pounding out rap songs on the wooden desk tops; some were looking at porno and stereo magazines; and others were writing letters home. I started asking about the class. I wanted to know when the teacher was going to begin teaching, if he was cool, and how often we were allowed to work on the vehicles in the garage. The other students basically laughed at me, and told me to get with the program. As I came to learn about most other vocational programs in the FDOC over the next 20 years, the vocational class was a scam. From my first day assigned, I watched incredulously as the hoax unfolded…. [T]here was no teaching. The students told me not to make a big deal out of it, because they were happy to be able to laze around and get gain time for doing nothing.

Griffith had entered the prison system after living on the streets as a teenager and becoming addicted to crack. This was a perfect opportunity to help him turn his life around, and it was squandered. Instead of teaching him a useful skill and integrating him into society, the state simply kept him in a warehouse for years on end. Griffith quotes from a number of other prisoners talking about how they are stuck, knowing they’re going to leave with no money and no skills. A Black inmate relates:

I feel it’s ridiculous. It puts me between a rock and a hard place. Me, growing up in poverty in the street life, it’s hard to step out of prison with nothing. With no rehabilitation, I’m gonna be subject to living the street life, ‘cause I don’t got the basic training to support myself. Also, me being so young, I got nothing but air and opportunity to try to better myself in prison. Pretty much, they just throw us in prison and we ain’t got nothin’ to do. What kind of job is someone like me gonna get with no real vocational or educational skills to get paid for. Instead of them just throwing their money away or building so many prisons, why don’t they ask us or take a survey on what vocations we feel we could do or be interested in..

The total lack of effort to educate or empower prisoners, Griffith says, and the mixture of slave labor and busywork, fosters a sense of futility, resentment, and cynicism in the prisoner. Many don’t see why they should care about trying to be part of a society that treats them like they are worthless:

“Until a person actually experiences an eight-hour day in a snake-infested ditch, with the brutal sun beating and the mosquitoes biting on his neck, and blisters bleeding on his shovel hand, he or she will have a difficult time understanding the disgust it promotes. Being ordered to do this day after day for months or even years without a penny of pay, while a spouse and children suffer without the financial compensation of his or her labor, creates a deep-seated hatred for society. Why should an ex-offender have empathy for society’s values when that same society put the inmate in a snake-infested ditch under armed guard, used strong-arm tactics to seize the fruit of his labor, and disenfranchised him or her for life after release? Loss of liberty for a crime is understandable. Slave labor and permanent assignment to a lower caste are not.”

Again, Griffith is a moderate, not a prison abolitionist. Can anyone reasonably disagree that making prisoners feel hopeless and resentful, and depriving them of any skills they could use to make it in the world outside, is foolish beyond belief? By being “dump[ed] into a warehouse of idle wolves” instead of being educated and trained for real jobs, prisoners are being set up to fail. The question they end up asking themselves, Griffith writes, is: “If the alternative to prison is a life of constant stress, sadness, and a struggle to survive, why not take the chance at avoiding them all by risking just one potentially lucrative crime?”

Griffith says that young inmates swiftly imbibe cynicism from those who have already served years and decades. He sums up the attitude with an imaginary (though, he says, very true to life) monologue given by an older prisoner to a younger one:

“They don’t give a damn about you, kid,” says the old con. “Just look around. You’re a number, a body that rakes in big bucks for officer paychecks. And when you get out, you’re still a number. You’ll always belong to the lowest class, with most of this country’s opportunities closed to you. You ain’t never gonna be a high-paid lawyer or a dentist or some other licensed professional. You’ll be released with fifty dollars and the clothes on your back. Them folks don’t give a damn if you’re homeless or starving a week after you’re released. And when you face the stresses of bills, remember that those same citizens will demand you to show a respect for work that pays peanuts. They’ll expect you to act civilized after warehousing you in a cage. Without concern for the training that’s gotta come before such dignity, they will expect you to work hard and suffer your poverty in silence. But then you fall back on your prison training and them same citizens are looking down the barrel of your pistol, they’ll beg you for mercy, a mercy they never showed when the guards was beatin’ your ass and writin’ false reports on ya. And the political types will say ‘We told you so,’ and more tough laws will get passed. They’ll get passed ‘cause the folks with all the dough will fund those con men who beat the drum the loudest for building more warehouses, the same warehouses that taught us hatred for work and despair for the future. That’s the truth son; they don’t give a damn about you, so make sure you get ‘em good and don’t get caught.”

Griffith himself doesn’t share this attitude. But he asks us to understand why it takes hold. It’s hard to deny a lot of what the “old con” says to the younger one. “The system itself offers no real alternatives of hope for escaping life as a permanent second-class citizen stuck in a lifetime of poverty,” Griffith writes. If you want to stop crimes from occurring, give people the hope that they can have decent lives. If you don’t, then what do you expect?

Griffith also documents a number of the hideous cruelties of the American prison system, including malnutrition and medical neglect. The passages on the medical system are particularly disturbing. Griffith recounts his own story, a ten-year drama in which he suffered multiple bacterial infections that went untreated and caused debilitating symptoms. His story of primitive dental care, and the agony after doctors refused to give him pain medication, is harrowing. (“As I paced in the dark, starving-hungry, with blood dripping from my nostrils, I experienced the most inhumane pain and suffering of my life.… I could not believe that so many people could, in concert with each other, knowingly and maliciously inflict such intense suffering on someone.”) He recounts stories of bad prison medical care across the United States, and says that in Florida it became a joke:

The incompetence by medical staff in the FDOC is so pervasive that the general prison population makes jokes about it, and all the inmates understand. For example in 2010, the mocking statement ‘pull pants down’ with a Vietnamese accent would automatically register a laugh from most prisoners at Tomoka [Correctional Institution] in recognition of one specific doctor’s incompetence. No matter what the prisoners’ medical complaints might have been, this doctor almost always related them to potential urinary, testicular, or prostate problems. An inmate might go in with a sore throat and come out after receiving a prostate exam. The next prisoner might go in with an ear infection and leave after a testicular exam. Most inmates just knew that a visit to this doctor meant an eventual order to ‘pull pants down.’ It was an ongoing joke.

For most it is not funny. For those inmates whose medical needs were neglected, the incompetence was a potential threat to their health. If this doctor said a thyroid problem was really an inadequate level of testosterone caused by some testicular dysfunction, his diagnosis became accepted law by the medical staff. Even when they knew he was refusing to properly diagnose and treat certain ailments, nurses would follow his orders and ignore his abusive practices. Repeated grievances against him were denied.

The other doctors were not much better.…

Griffith tells disturbing story after disturbing story of cruel medical neglect, recounting his horror as inmates tried to convince the staff to treat a mentally ill prisoner named Joey Constantino, whose spreading cancer was repeatedly dismissed as a “rash.” But the story that upsets him most, and that he is determined we should hear, is that of “Ziggy,” who was treated with unconscionable cruelty. The story deserves to be reprinted in full:

Around October of 1994, I met a prisoner named Ziggy. We were housed on the same hallway. Ziggy was one of those guys who never fit in with the crowd. He was a nerd with a hooked nose, shifty, nervous eyes, and black plastic, horn-rimmed glasses. He was timid, always carrying his big head down, scared to make and hold eye contact with the convicts around him. Ziggy never bothered anybody, and he always had some thoughtful, intelligent advice to offer when someone needed a genius insight. Ziggy was rumored to have an IQ of 140. I made a pact with myself that one day I would tell the world about what happened to him.

One evening, around 5:30 PM, I heard a loud thump a couple of doors down from my cell. The noises sounded like someone had dropped a bowling ball wrapped in cloth onto the floor. It was Ziggy on his cell floor, writhing and jerking his head, banging his hand in a grand-mal seizure. I quickly grabbed a pillow off of his bed and placed it under his head to protect his skull from any further trauma. Other inmates joined me in trying to limit the damage to his limbs while someone ran to inform the guards that he was in need of medical attention.

About twenty minutes later a medical technician (MT) came and knelt beside Ziggy, who was becoming groggily conscious, but certainly not to a normal state. The MT took his vital signs, asked him some questions, and then began packing her medical bag. She gave Ziggy some Tylenol for his headache, told him he would see a doctor in a few days, and exited the dormitory. Ziggy was still sitting on the concrete floor beside his locker.

I was incredulous. I could not believe that the MT could not see Ziggy’s slurred speech and grogginess as a sign of something wrong. On her way out I quickly asked why she was not doing something for him. I explained how severe his seizure had been and how far from his normal self he seemed to be. Since she was not familiar with his normal state, I wanted to make sure she understood that he seemed to be suffering. The MT said that she had a ‘ton of things to do,’ that she had taken his vitals and they were fairly normal. From her viewpoint, until he went to see a doctor there was nothing more she could do.

Fifteen minutes after she left, Ziggy was having his second seizure. This time he began frothing at the mouth, and seemed to be choking. We repeated the pillow and other precautions, and the MT returned after about ten minutes. She was visibly angry, with her brow creased and her lips pursed. Ziggy had again regained consciousness.

‘Now Ziggy, I don’t have time for this,’ she said curtly and knelt beside him. Rather than take her instruments out, she simply took his pulse and stood up.

‘You guys,’ she indicated to us, ‘grab him and help him into his bed.’

Another prisoner and I helped him into his bunk and placed a sheet over his body to make him comfortable. I was furious because I realized this meant the MT was going to leave Ziggy in the dormitory again, rather than taking him to the infirmary for observation and a call to the doctor. When I angrily asked about this, the MT told me to mind my own business. She left the dormitory in a rush.

Thirty or forty minutes later, Ziggy was having his third seizure. The episode only lasted about three minutes and then Ziggy remained unconscious. The MT begrudgingly had Ziggy rolled to the infirmary. From the time of Ziggy’s first seizure at 5:30 P.M. to the last one around 7:20 P.M., almost two hours had passed before he was finally rolled to the infirmary. That was two hours of deliberate indifference to Ziggy’s medical needs, a period of indifference during which he could have been transported to a hospital, and a period of indifference that cost him his life. He was pronounced dead the next morning.

What Griffith saw was not an aberration. The Vera Institute reports that the state of healthcare behind bars is “abysmal” and there are virtually no standards, which is one reason that each year someone spends in prison takes two years off their life expectancy. (It’s one reason U.S. life expectancy is lower than in peer countries.) When I worked for a summer at the ACLU’s National Prison Project, I had to read endless disturbing first-person testimonies from inmates whose worsening health conditions were left untreated despite repeated pleas for help. (I vividly remember the story of a man whose testicle grew larger and larger, and was excruciatingly painful, and who was totally ignored.)

The U.S. Supreme Court has held that deliberate indifference to prisoners’ medical needs is cruel and unusual punishment and prohibited under the Eighth Amendment, but reading Griffith’s book, it becomes obvious why the ruling only exists on paper. Griffith goes into considerable detail explaining the failures of the grievance process, and the barriers facing prisoners who try to access courts for remedies to abuses. Prisons are places where cruelty is both normalized and unaccountable, and since there is so little oversight of them, mistreatment flourishes and is not reported on. (Things were particularly bad during the height of the pandemic, where many prisons took few precautions against the illness, leading to many unnecessary inmate deaths. This magazine published a powerful article by widow Cassandra Greer-Lee, whose husband died of COVID in prison, arguing that Democrats were just as bad as Republicans in treating inmates’ lives as worthless. A prisoner I had once worked with myself, who was 72 years old and entirely harmless, died of COVID in a New York prison after the state refused requests by Release Aging People In Prison to grant him clemency. Rest in peace, Mr. Smalls.)

Griffith goes systematically through every aspect of the social failure that is our prison system. He shows how it ruins countless lives for no reason at all. He gives the example of Florida resident Hope Sykes, who was 18 years old in 2010 when she was arrested for selling 25 hydrocodone pills. Sykes was sentenced to 15 years in prison, of which she served 12. Griffith bitterly notes that “pharmaceutical companies sell these pills through pain clinics or ‘pill mills’ by the hundreds of millions,” with Sykes doing time while pharmaceutical executives profit.

Griffith spends a good deal of time discussing supervised release programs, and the way they set ex-offenders up to fail. The theory is that if a small mistake can send you back to prison, people will be on their best behavior. In fact, Griffith says, in the real world the effect is often the opposite. If ex-offenders know that the arbitrary whim of a parole officer makes their freedom constantly conditional, they can become resigned to the idea that they’ll never escape the clutches of the prison system, that there’s little hope. Griffith himself recalls that as a young man, he was sent back to prison while on supervised release, after a car malfunction caused him to violate his curfew.

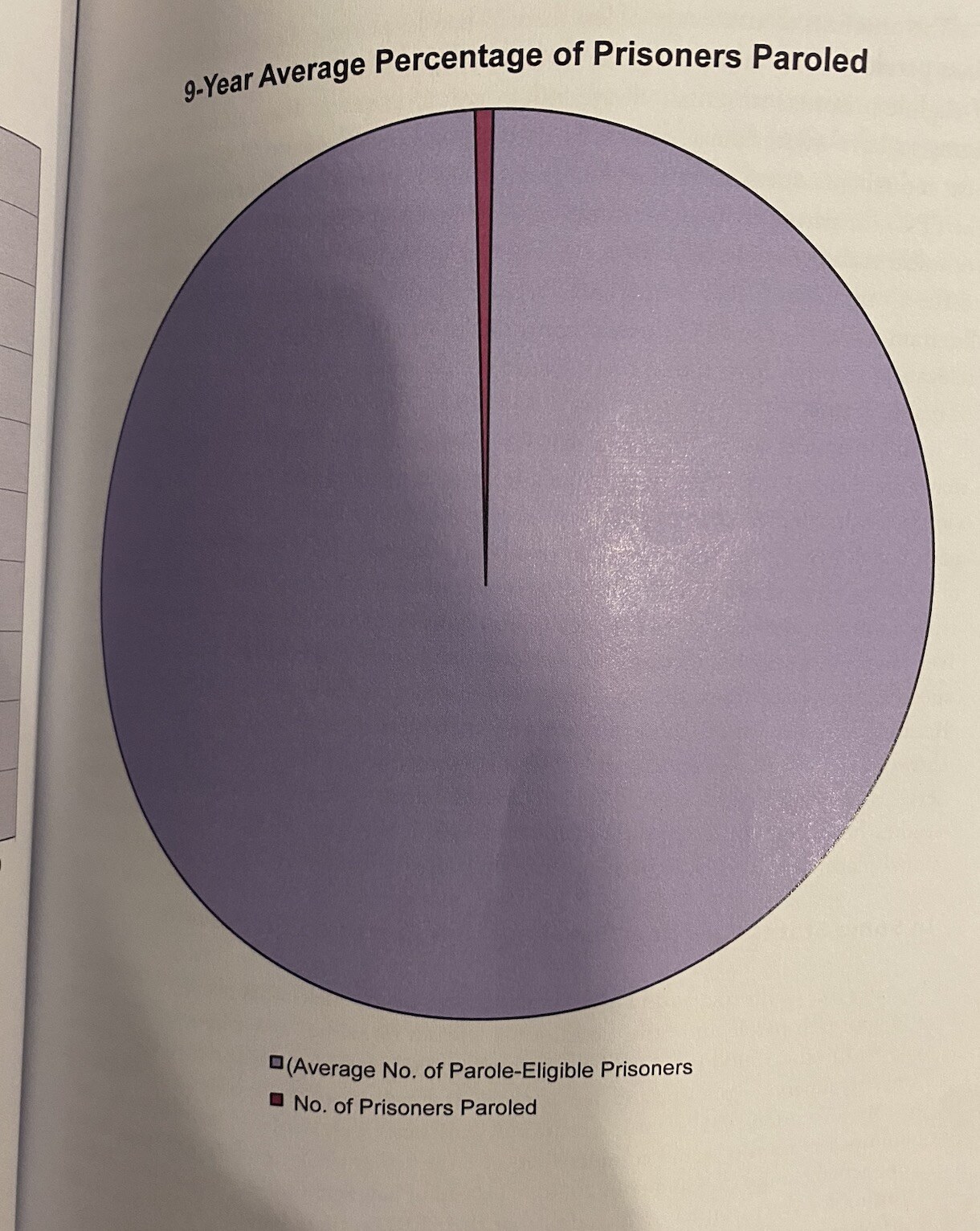

Even worse, he says, is that people aren’t actually getting paroled who should be. In Florida, parole is virtually a fiction, with eligible prisoners routinely denied by committees that have only a cursory knowledge of the facts of their case, and whose guesses about the likelihood of recidivism are usually based on totally unfounded speculation.

There are other common misconceptions that Griffith refutes. The rationale behind long sentences is that they serve as a deterrent. But Griffith notes that not only are old people unlikely to reoffend, making their incarceration a useless waste, but long sentences generate hopelessness and make people feel less inclined to try to change anything. There is a “diminishing aversion to incarceration” among prisoners, Griffith says, that “politicians would have little knowledge of.” Initially, fear of being arrested and going to jail might affect conduct, but Griffith says that eventually he “learned to do time,” and simply got used to it.

Griffith admirably takes a stand in defense of people affected by drug addiction. He notes that “some mind-altering substances create such a combination of irresistible need and lowered social inhibition that an otherwise decent person’s moral certitude can deteriorate overnight.” Yet “for those who have never become dependent on one or more of the addictive substances sold on the street, the idea that someone can just click an addiction ‘like a bad habit’ is common.” He notes forthrightly that “drug treatment facilities are very expensive. People in poverty cannot afford them.… For addicts with wealthy families, intervention usually occurs before they become financially desperate.” We need to understand “just how complete that loss of self-control is” and understand that “showing intolerance and neglect for the needs they have only worsens the problem.”

And yet, Griffith notes sadly, “harsh consequences to people accused of crimes no longer activate much sympathy or public interest.” He’s right about that, and I fear it’s getting worse. For a period of time following the publication of Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow (2010), mass incarceration was hotly discussed. Today it seems to barely register on the agenda. Even those interested in reforming the criminal punishment system seem to have shifted focus to policing over prisons. I am no defender of the police, but we’ve also got to keep our eyes on those locked away by the millions. Unfortunately, there has been a revival of “tough on crime” rhetoric since the eclipse of the George Floyd protests, and I’m worried that Democrats see anything to do with criminal punishment as a loser of a political issue that they don’t want to touch, since Republicans will accuse them of wanting to let all the murderers run loose in the streets.

But reading Griffith’s book was a bracing reminder of the problem of prisons. Griffith shows incontrovertibly that mass incarceration is both morally indefensible and stupid from a policy perspective. He does not himself entertain the idea of a world without prisons, as some of us do. In fact, he confines himself to solutions that no reasonable person should be able to oppose: at the very least, every prisoner should be able to go to school and learn things and make a decent wage that they can use to build savings and support their families. At the very least, they should be given good medical care, because it’s not easy to work on improving yourself when you’re suffering from a debilitating illness. At the very least, they should be able to see their families regularly. (Griffith recounts the difficulties he had in getting placed in a facility within a reasonable distance of his family, who had to stay in a hotel if they wanted to see him. This all but ensures that poor families will see their ties shattered.)

Griffith didn’t tell me much that I hadn’t read before. His writing is unpracticed, and his politics are a bit unformed. But he reminded me of some simple truths that it’s very easy to forget.

Griffth ends his book with a message to prisoners everywhere.

It was not only a book to teach students, professors, and policymakers what is needed to reduce the prison problem. It was also a book to share the human side, your side of the story, so that people can better understand what is happening to so many of us. I spent over twenty years locked up, and you are holding one of my dreams in your hand. They said when I was twelve years old that I was an emotionally handicapped person. They said I had a borderline personality disorder and that I was a slow learner. I say they didn’t understand me. If I can do it, so can you. Believe in yourself. Follow your dreams and if you don’t give up, I promise that you will find your happiness.

The words are heartbreaking in light of Griffith’s ultimate fate. Shortly after the book’s publication, he was rearrested, accused of a crime he denied having committed. Even if he was found not guilty, however, Griffith faced years more in prison, since the arrest itself was a violation of his parole. Griffith couldn’t face returning to prison, and ended his life in his jail cell instead. Facing The U.S. Prison Problem was written during the very short period (about two years) of his adult life where he was permitted to experience liberty. In that period, he showed himself to be thoughtful, diligent, and insightful. He would have made a stellar sociology professor or lawyer. Instead, all we have is this out-of-print book, the testament that he put his every last ounce of energy into. It was his effort to tell the country that we needed to do better. Not many people listened when he wrote it. But I’m listening, and I hope you are, too.