What Chasten Buttigieg Has to Tell Us

‘I Have Something to Tell You’ provides a blueprint for an LGBTQ politics whose only challenge to American empire and capitalism is that our most oppressive institutions should be queer-affirming.

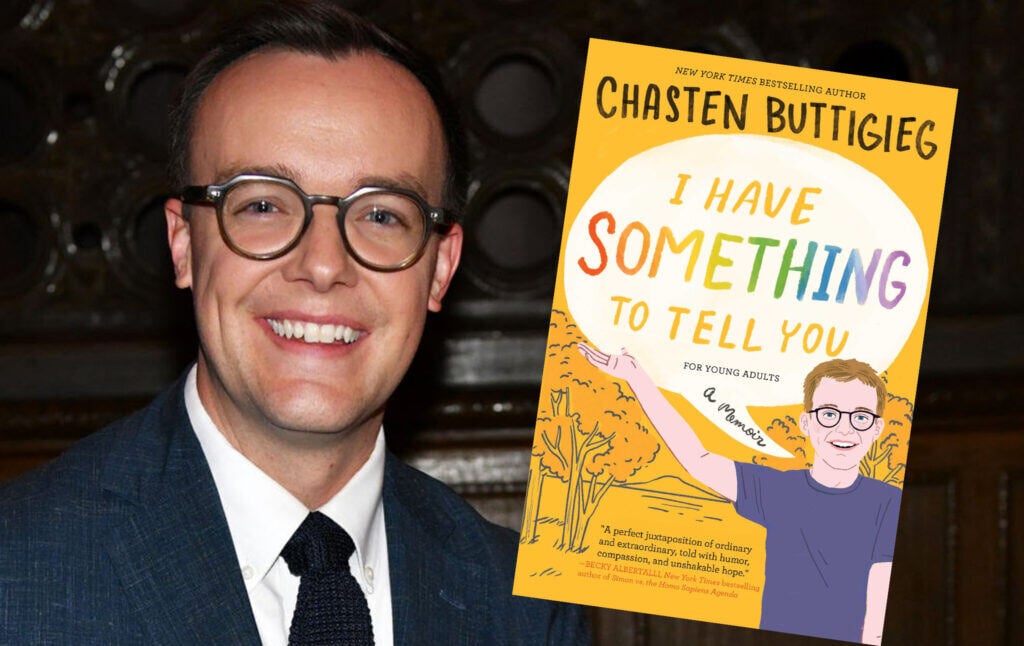

Chasten Buttigieg, I Have Something to Tell You—For Young Adults: A Memoir (Simon & Schuster, May 2023), adapted from I Have Something to Tell You: A Memoir (Simon & Schuster, June 2021)

Chasten Buttigieg, husband of Pete Buttigieg and once a candidate for the position of First Man, is 33 years old. So, of course, he has now fulfilled one of the two legally required conditions of what is known as the “Jesus year”: to write a memoir (the second is to create a podcast, undoubtedly on its way). These days, one needn’t have lived too long before one’s life is deemed, let’s coin a term, memoirific. Did you suffer some trauma growing up (keeping in mind that “trauma” is such an elastic term these days that it’s practically meaningless)? Does any part of your identity fall outside the conventional norms (white, hetero, cis, male)? Is your husband a constantly aspiring presidential candidate whose life looks like a meticulously written script for the movie, “Pete Buttigieg, First Gay President of the United States”?

Congratulations! You’re Chasten Buttigieg, and you’ve just published a memoir titled I Have Something to Tell You. Or, to be accurate, you’ve just turned your previously published memoir into a version for a Young Adult audience. Why rewrite a memoir for young adults? might be the question. “Why not?” was clearly the answer over at Simon & Schuster, which had presumably seen the previous iteration of this book do well enough. Or, perhaps, the publisher saw the prospect of finding yet another lucrative market, the one targeted at the people henceforth referred to as “young adults.”

Make no mistake: Chasten Buttigieg’s memoir is in fact Pete Buttigieg’s memoir. It’s not just that being the husband of a prominent politician means that, of course, Chasten’s words will be scrutinized and evaluated as carefully as Jacqueline Kennedy’s white gloves and pillboxes. Rather, it’s that Pete Buttigieg has been preparing for the presidency since almost as soon as he could walk: one pictures him as a tiny tot, carrying a tiny briefcase with the words “Office of the White House” scrawled in a childish hand. (In fact, at the tender age of 11, he asked for a copy of John F. Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage as a birthday gift.) Pete’s life has been as carefully curated as a Spotify playlist, and his dogs, Buddy (also the name of Bill Clinton’s dog) and the recently deceased Truman (the Americana theme stretches every which way in this household), were clearly handpicked to promote the best vibes. Buddy is one-eyed, proving that the Buttigieges are compassionate, and Truman was a houndish dog (their mostly inactive Twitter account is @firstdogsSB). Both were, of course, rescue dogs. During his campaign for the presidency, Pete even ran a campaign commercial, “Pete and Dogs,” apparently meant to demonstrate that dogs love him (the fact that it ends with Buddy snoring may not have sent the intended message).

Even their children could not be more perfect. For one thing, they are twins, and there are few things cuter than twin babies (besides cats, which are infinitely cuter). And these are biracial children, a handy defense when people bring up Pete Buttigieg’s troubled relations with his Black voters while mayor of South Bend, Indiana. As Nathan J. Robinson pointed out in an extensive review of Pete’s (first, so far) autobiography, Shortest Way Home: One Mayor’s Challenge and a Model for America’s Future, “South Bend African Americans make half of what South Bend whites make. They’re twice as likely to be in liquid asset poverty as whites. Their unemployment rate is nearly twice as high.” Buttigieg attempted to win over African American voters during his presidential run, but it was too late, and he failed miserably in South Carolina: to his surprise, Black voters turned out to be smart people who knew his history. Given their talent for curation, it’s hard not to wonder if the Buttigieges didn’t also choose their children as carefully as Melania Trump chose her outfits. This doesn’t mean that the pair don’t love their incredibly adorable children, but given that even Chasten looks like he was chosen from a catalog of “Good Gay Men,” it’s safe to say that even the most seemingly personal details of Pete’s life are carefully chosen. (The two met on Hinge, so there’s an element of catalog-hunting in all this.) Recall that this is a man who left his job as mayor of South Bend—a job that voters elected him to do—for seven months, just so that he could park himself in a safe administrative military position in Afghanistan and thus, in later years, be able to declare himself a war veteran when he ran for president. As I pointed out in “Pete Buttigieg Is Still Playing,” even in his position as Transportation Secretary, Pete has so far been The One Who Does Nothing Until Compelled to Take Action—his inadequacy in dealing with crisis situations came to the fore during the Norfolk Southern train derailment disaster earlier this year.

Given all this, it’s unsurprising that I Have Something to Tell You is a political manifesto disguised as a deeply boring All-American story, in keeping with Pete’s entire political career so far. Pete Buttigieg’s life has been quietly and meticulously engineered to be the perfect embodiment of American values, just gay. Shorn of the kind of details that only seem special because of a historical accident—Chasten met Pete and they fell in love and married and live happily with their twin biracial children and two dogs—there is very little to recommend. It’s fine to be boring—most of us might wish for lives that are such, at least for periods of time, so that we can get some rest—but maybe don’t write a memoir. And then twist it around into a tale for “young adults.”

There is not enough time and space for an adequate history of childhood and “young adult” literature, except to point out that both are invented categories. Until the 19th century and when child labor laws were enacted (Charles Dickens, who had worked as a child in a blacking factory to support his family, was a major force behind them in England), the category of “childhood” was largely unknown as a political demographic. As for fiction, while there were stories meant for children, the category of “young adult” is a relatively new one, invented by publishing houses in the mid-1960s as they looked for new markets. It’s a vague and capacious term—which explains, for instance, why Chasten Buttigieg’s book is listed as being for anyone from “12 and up.” That’s a really broad category.

So, who is this book for? And what purpose does it serve, besides being a rah-rah cheerleading song for the political career of Chasten’s husband Pete? And, in that context, what can we make of Pete Buttigieg’s life story as told through his loyal and devoted husband? What lessons might “young adults” learn from it? Should they?

Chasten’s Early Life

Born Chasten Glezman (he took his husband’s name), Chasten was born and raised in Traverse City, Michigan. There are some poignant sections here that remind us that while very, very few LGBTQ children growing up in very specific urban neighborhoods might feel safe and cherished as they express or explore their identities, a great number still live lives of relative isolation and pain. Chasten writes movingly,

[A]s the truth grew clearer and clearer, I pushed it deeper and deeper into the closet. By high school, it felt as if my heart were on the outside of my chest: exposed, vulnerable, and easy to break.

At one point, he writes, he was being beaten up by school bullies who only stopped because his elder brother intervened—but while the latter walked home with him, he never discussed the incident, then or after, something that had to be heartbreaking for a young boy. Chasten writes about often being reminded of such isolation when he meets older gay men still living closeted lives who are happy to see an out gay candidate with his partner on the campaign trail. He has very little to say about trans people, but that’s typical of a book that sees “gay” only in normative, cisgendered terms: like the mainstream gay community, which only takes up the issues of trans people as a way to drive donor funds, the Buttigieges will doubtless turn to them only when convenient.

Unlike many other gay teens and despite the coldness of his brother, Chasten still grew up in a loving family—upon coming out to his grandmother, she simply reached out to clasp his arm and said, “I know, Chassers. And I love you just the same.” Soon after he came out to his mother, he fled the house and spent weeks living in his car or on his friends’ couches because he was so convinced that his parents would reject him. (In a Washington Post profile, he recounts hearing one of his brothers declaring, “No brother of mine…” and it’s unsurprising that he felt unwelcome in his own home). His parents worried about him and called and tried to get him to return, which he eventually did. His brother Rhyan has told the Post that while he loves Chasten, he does not “support the gay lifestyle,” a clearly homophobic reaction. Families are complicated—sometimes they change over time, and sometimes only in bits, but Chasten’s parents appear to be as supportive as they could be, even walking him down the aisle at his wedding to Pete. Of his father, he writes, “In many of the circles I was in, there was a very specific type of masculinity, or manliness that needed to be displayed in order to be seen as a ‘tough guy.’ He taught me that a quiet man is no weaker than the loudest in the room, and that love and tenderness and vulnerability aren’t things to be ashamed of.” His parents were not well off, and while they were able to keep Chasten and his two brothers fed and housed, they had to work multiple jobs to make sure they had money to pay the bills. This included selling Christmas trees every winter, an enterprise that included all the children helping with sales, in addition to their landscaping business. His mother took shifts as a nursing assistant to make more money.

Chasten writes about all this as signs that his parents were and are the best kind of Americans: hardworking people who throw themselves into every opportunity so that they might get by. This is hardly what we should want for our parents in their old age or, really, ever: to have to constantly grind away at multiple jobs just to be sure that there is enough—for clothes, food, heating—while always fearful of emergencies because even a child’s broken foot or tooth could send the family over the edge and into bankruptcy. But, of course, this is what liberal politicians like the Buttigieges hold up as ideal—recall that Michelle Obama spoke approvingly of teachers working without pay to keep their unfunded schools going. There are signs that Chasten understands that such politics are bullshit, especially as he acquires student loans after college, but in the memoir he constantly harps on the work ethics of his parents because, really, how could he not? Can a First Man really afford to take the view that the United States is a country that forces its not-rich to live draped on the grindstone of eternal work till they die, always afraid that a single medical emergency might send them into catastrophe?

As for gay politics: Chasten’s politics are, unsurprisingly, conventional. Echoing many conservative gay activists, he cautions his young reader that “we have to get a place at the table.” He goes on, “If you have a seat at the table, then you get to be part of the conversation and decision-making.” Later, he writes about the AIDS crisis of the 1980s, “Because HIV/AIDS was affecting primarily gay people, the government was very slow to get involved, since it was unsupportive of the LGBTQ community in general.” In such bland terms, he erases one of the darkest eras of stigma—one that left millions unable to even find hospital beds or graves to be buried in. And he leaves out one of the richest and most explosive parts of queer history: when very, very angry queer people of groups like ACT UP and Queer Nation literally broke the table, as it were, and forced the government and pharmaceutical companies to create access to life-saving medications.

When it comes to public figures and cultural history, Chasten is similarly bland and regurgitates all the accepted narratives. About Ellen DeGeneres, he writes that she had been forced off the air because she came out as gay, and that Matthew Shepard had been murdered for the same reason. In fact, both stories are more complicated—DeGeneres actually never stopped working, even as an out lesbian, and her “coming out” episode on Ellen was the highest rated of the show, which continued for one more season. After Ellen, she was cast in yet another sitcom, titled The Ellen Show where she played.…an out lesbian, and then went on to her talk show, The Ellen DeGeneres Show, which stayed on the air from 2003 to 2022. (By then, everyone and their grandmother knew of her gayness.) The show’s end had nothing to do with her lesbianism and everything to do with several complaints involving racism and sexism in an extremely toxic work culture behind the scenes, belying the shiny, happy facade of the host.

Similarly, while Matthew Shepard was certainly brutally beaten, the causes behind his death have long been detailed as more complicated: JoAnn Wypijewski wrote a famous 1999 piece for Harper’s, pointing out that the incident was deeply entrenched in a nexus of class, sex, and the shabby economy of Laramie, Wyoming. More recently, Stephen Jimenez de-mythologized Shepard’s life, bringing more evidence that the death was part of a drug deal gone awry. None of this excuses the murder, but the background of poverty and economics makes a simple tale of homophobia more untenable and locates sexuality within larger contexts.

Chasten Buttigieg pushes aside such complications surrounding living and dead public figures in favor of heroic narratives that present much simpler tales: brave gay people fighting against all odds and sometimes facing the worst consequences. And, certainly, the current political climate on LGBTQ issues is deeply troubling: recent anti-trans legislation has mushroomed across the United States, leaving trans children, youth, and adults under threat of attack and erasure (we will note, again, that Chasten makes no significant mention of trans people in the book), and gays and lesbians are hardly much safer amidst a rising tide of conservative politics. But if a memoir about gay life and its possibilities is to be honest with its audience, it needs to be less afraid of the raw truths facing its readers.

Growing Up Chasten

In the “adult version” of his memoir (this is an awkward phrase, but we strain to find another for such a strange literary form), Chasten writes explicitly about a sexual assault he suffered at the age of 18. He was ultimately able to fend off his attacker, a man whose sexual advance quickly turned violent, but that experience left him feeling shocked, shaken, and suspicious of other people for a long while. This incident is left out of the “young adult” version.

It could be argued that children as young as 12 don’t need to read about sexual assault, especially in a book that’s designed to nurture their sense of self and safety as they think about their sexual identity. But what is the point of discussing sexual identity and not pointing out that it often involves moments of real danger? Why not use the incident to highlight the complexities of navigating the world of sexuality and desire, to perhaps teach—as so much of young adult literature seems doomed to do—“youth” how to anticipate, prepare for, and handle awkward situations that might place them at risk of such attacks?

Instead, Chasten’s dominant message with this book is about “authenticity”—a meaningless word that is nevertheless taken up by gay activists and “allies” like Cyndi Lauper whose “True Colors” foundation makes a virtue of telling young LGBTQ people in particular to live in their “true” selves. We could argue that this is merely encouragement to be themselves. But authenticity, like “equality,” is a trap. Chasten writes, “I hope that by reading about my journey, you will feel compelled to keep sharing yours as authentically as you can.”

What does it mean to be authentically queer? In gay organizing, “authenticity” is code for “be fabulous and the kind of LGBTQ person who is easily recognized as such” and “make sure you find a life partner.” Towards the end, Chasten writes that the answer to the question, “If you could go back and tell your younger self one thing, what would it be?” is “You’re going to fall in love both with yourself and with someone else.”

But why? Why tell someone, potentially a mere 12 years of age, that “falling in love” is so important? What if the lesson were, “The world is actually, sometimes, a scary dark place, and here are the warning signs to look out for.” Or, “Never believe that someone’s validation of you is so important that you let them take you into a strange room.” Or, “The world has, historically, refused to give queers even a semblance of life itself and we only got what we needed by breaking a lot of things, including their dinner table, and screaming in the streets.”

Instead, Chasten offers up a vision of queer life for young people that is at best a series of affirmations born out of Gay Straight Alliance culture. Like his and Pete’s life together, it’s carefully calibrated to ensure that an imagined and very normative straight person won’t be offended by anything, like references to queer death or sex or anger or social movements that aren’t just about gaining access to the economic advantages of marriage. Youths are admonished to be happy, to be authentic, to believe in hard work, no matter how grueling their work might be—it will all work out, and a romantic interest will make it all go away.

What remains to be told? What would have been an actual “memoir” for “youth”? And is Chasten responsible for saying more?

Lessons from Chasten

In his essay “On the Moral Responsibilities of Political Spouses,” Hamilton Nolan looks at the life and politics of Cheryl Hines, the wife of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Kennedy—an anti-vaccine conspiracy theorist correctly described by Nathan J. Robinson and Lily Sánchez as a “Lying Crank Posing as a Progressive Alternative to Biden” in these pages. Hines, well known for her role on Curb Your Enthusiasm as Larry David’s progressive wife, also named Cheryl, has been able to demur when asked about her political beliefs, but Kennedy has spoken often about her tremendous influence on him. While it’s customary to see politcal spouses as secondary, silent partners, Nolan asks, “Is Cheryl Hines willing to sit down with the children of someone who listened to RFK Jr. and decided not to get vaccinated and died—or with the mother of a depressed teenager who didn’t take their antidepressants and fell prey to suicide—and say to those people, “Your family had to die, so that I could have peace in my own family”?

It’s more than likely that the liberal press will be soft on Chasten, just as it ignores the moral culpability of spouses like Hines: even mild criticism of a gay candidate and his (adorable, handsome) family can be dismissed as homophobic by the Buttigieges and their supporters in a very, very powerful mainstream gay lobby. But Chasten can’t just be the innocuous gay man who brings a reassuring and Buttigiegistic worldview to the masses: “Yes, we’re gay, but fear not: we will unleash wars and ignore poverty, just like everyone else.” To use a phrase that originated in radical feminist and queer circles, the Buttigieges enable a pinkwashing of American imperialism. The problem is not that their lifestyles are too normative, but that nothing about their vision for the world is a departure: their gayness provides a progressive cover for a politics that’s all about preserving the status quo. They could be men who walk around in leather chaps with multiple partners, and their politics would still be troubling: “alternative” lifestyles are no guarantee of radical or even mildly progressive politics, as anyone who has walked into any leather shop or bar in Chicago’s racist, classist, and sexist gay neighborhood Northalsted can tell you (this is sadly true of the city’s entire gay scene, but that’s a different essay).

I Have Something to Tell You presents a gay life that, having overcome some obstacles, is nevertheless able to purposefully stride towards an apolitical “American” life. Along the way, it recasts vital parts of American and gay history. In this version of America the Gay, gayness is translated as either a tragic life to be overcome or as one that can only be happy when straight people first pity you and then allow you to marry. Inconvenient complications, like angry queers organizing around AIDS or demanding rights outside of marriage, are quietly brushed away. It’s an admonition to “youth” to only be a certain kind of gay. As a political manifesto, I Have Something to Tell You provides a blueprint for a gay constituency whose only challenge to American empire and capitalism is that our most oppressive institutions should be queer-affirming.

Chasten and Pete will serve as the Ken and Ken dolls on top of a wedding cake, obscuring any memory of a time when queer radical action meant demanding the seemingly impossible: universal healthcare, an end to poverty, housing and security for all. Chasten has something to tell us, sure, but it’s a well-modulated, soothing whisper, telling tales of good gay people sitting decorously at the table. Queer people have suffered and continue to suffer enormous harm not just because they’re queer but because capitalism only sees their worth when their identities can be deployed to further its own ends, and its spits out those too inconvenient to have around (angry radicals, trans queer youth demanding a say in their own health, and so on). But youth, across sexualities and whatever their age, deserve more and better. They deserve to know their radical history and that the world can be an exciting place for them, but they also need to know that they should avoid and ignore decorous gay men whose lives, fabricated across multiple, anodyne memoirs, serve to erase both the darkness and the rich complexity of real lives.

Update: This article originally described the Buttigieg children as surrogate-born. While this was based on previous reporting using the term, the Buttigiegs have said the children are adopted. (The story has attracted controversy.) The original descriptor has been removed to ensure accuracy.

Yasmin Nair is co-founder of the radical editorial collective Against Equality, on the editorial board of the Anarchist Review of Books, and an editor at large at Current Affairs. Her current writing projects include a young adult novel about coming out.