The Espionage Act is Bad for America—Even When it’s Used on Trump

A relic of the First World War that helped destroy the anti-war left, the Act remains a threat to news outlets, political organizers, and anyone else who might challenge American militarism and the surveillance state.

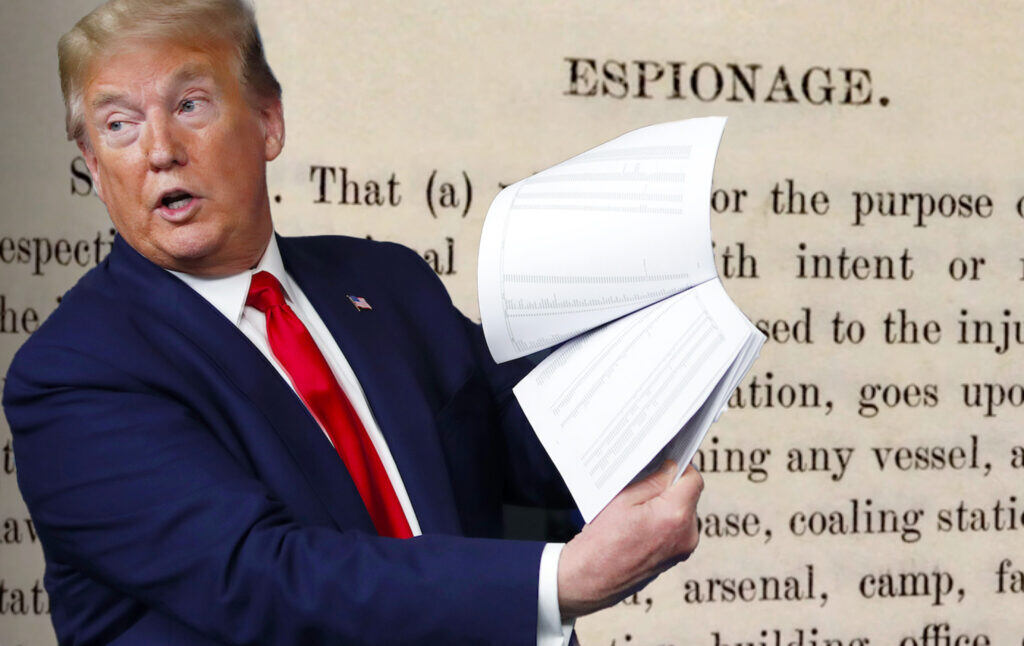

Almost immediately after Donald Trump was indicted for federal crimes under the Espionage Act of 1917, liberals began celebrating. “This feels like justice coming,” crowed editor Michael Tomasky in the New Republic before speculating that “if there is any justice left in this country, he [Trump] will die in a jumpsuit that matches his cratered skin.” (Apparently some people still haven’t tired of ‘orange’ jokes.) At MSNBC, columnist Michael A. Cohen called the indictment “a reason for genuine celebration” and “a great day for democracy.” The New York Times, meanwhile, interviewed 60 prominent Democrats, and found that “the satisfaction is nearly universal” among them, with many “relishing the possibility that Donald J. Trump will get his comeuppance at last.”

On one level, these reactions are understandable. Trump has been committing odious acts his entire life, both personally and politically, and if the consequences have finally caught up with him, that would be no bad thing—especially if his legal troubles can prevent him from regaining the presidency. Still, I can’t agree with Cohen that this indictment represents “a great day for democracy,” precisely because it’s the Espionage Act that’s being invoked. In the clamor of commentary around Trump’s case, few people seem to have stopped and considered what the Act actually is, and why it was written in the first place. Since its creation in 1917, it has had a long and shameful history, in which it has been used to harass and imprison anti-war activists, whistleblowers, and anyone else who opposes the actions of the U.S. military and intelligence agencies. At its core, it’s a repressive, anti-democratic piece of legislation aimed at gutting the constitutional right to free speech. Even if the Espionage Act seems politically convenient right now, its continued existence is a threat to any semblance of a free society—arguably more so than Trump himself.

Really, calling it the “Espionage Act” is misleading. When most people hear the word “espionage,” they think of something fairly specific—the actions of a spy who, like the infamous Benedict Arnold, intentionally hands over their country’s secrets to a hostile nation. But “espionage” in this sense has been illegal since the drafting of the U.S. Constitution. It falls squarely under the Article III provisions against giving “aid or comfort” to a national enemy, otherwise known as treason. What the Espionage Act of 1917 criminalizes is a much broader range of behavior, including:

- Anyone who, “having possession of, access to, control over, or being entrusted with any document, writing, code book, signal book, sketch, photograph, photographic negative, blue print, plan, map, model, instrument, appliance, or note relating to the national defence, wilfully communicates or transmits or attempts to communicate or transmit the same and fails to deliver it on demand to the officer or employee of the United States entitled to receive it”

- Anyone who “shall wilfully cause or attempt to cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, refusal of duty, in the military or naval forces of the United States, or shall wilfully obstruct the recruiting or enlistment service of the United States” during a time of war

Notice the vagueness of the language in that first clause, and the wide latitude it gives for prosecution. There’s no requirement that the information involved be classified—a distinction that wasn’t created until 1951—only that its contents relate to “the national defence” in some way. Some legal experts believe this will be the Achilles’ heel in Trump’s defense, since even if he could declassify documents “by thinking about it,” they would still contain defense information. Looking beyond Trump, though, it’s a worrying standard, because virtually any information about U.S. military policy (that the government didn’t explicitly approve for release) could be considered to fall under the Espionage Act’s purview. As Guardian journalist Trevor Timm points out, “if you read just the text of the law, it is being violated almost daily by reporters at every major paper in the country.” The Act contains no safeguards for the rights of the press to report on military matters, nor any acknowledgement that citizens in a democracy have a right to know what their leaders are doing. Instead, it amounts to a declaration that the state has absolute control over certain kinds of information, above and beyond democratic accountability.

To understand how such a wildly undemocratic piece of legislation came to be, it’s necessary to reach back to the Espionage Act’s first decade and examine the historical moment that produced it. The year 1917 is the pivotal one, as it saw twin political upheavals in the United States: first, the country’s entrance into World War I, and then a groundswell of anti-war resistance from the left. In his Joint Address to Congress declaring war on Germany, then-President Woodrow Wilson made it clear that his administration would deal harshly with wartime dissenters. With dictatorial bravado, he asserted that “true and loyal Americans” would “be prompt to stand with us in rebuking and restraining the few who may be of a different mind and purpose,” and promised that “If there should be disloyalty, it will be dealt with with a firm hand of stern repression.” All he lacked was a legislative framework for that repression—and just two months later, pro-war forces in both the Democratic and Republican parties provided it, pushing the Espionage Act through Congress with little time for debate or deliberation. With its strict constraints over public speech, especially concerning “the national defence,” it was the perfect vehicle for Wilson’s agenda—-not just to safeguard the nation’s secrets, but to crush the anti-war left.

Supporters of the war had good reason to be worried. Since 1914, socialists and anarchists around the world had condemned the Great War (as it was then known) as a senseless frenzy of violence, instigated by the moribund royal families of Europe and their competing claims on colonial power, and agitated for working-class rebellion. In the U.S., some pointed to financiers like J.P. Morgan—who, by 1916, had extended $500 million in loans to Britain and France—as the primary figures lobbying for the U.S. to enter the fray. In his newspaper The Jeffersonian, Populist Party leader Thomas E. Watson had nothing but scorn for Wilson’s pro-war rhetoric, painting the president as a tool of Wall Street:

“The World must be made safe for democracy,” said our sweetly sincere President; what he meant was, that the huge investment, which our Blood-gorged Capitalists had made in French, Italian, Russian, and English paper must be made safe. Where Morgan’s money went, your boys’ blood must go, ELSE MORGAN WILL LOSE HIS MONEY!

When war was actually declared, and with it the conscription of American workers, this anti-war activism went from a question of abstract principle to one of immediate life or death. Across the country, Socialist Party leader Eugene Debs made fiery speeches urging young men to resist the draft, often attracting crowds of thousands. Meanwhile, Charles Schenck—the General Secretary of the party’s Philadelphia chapter—distributed 15,000 pamphlets condemning the push to war as undemocratic:

The people of this country did not vote in favor of war. At the last election they voted against war. To draw this country into the horrors of the present war in Europe, to force the youth of our land into the shambles and bloody trenches of war-crazy nations, would be a crime the magnitude of which defies description. Words could not express the condemnation such cold-blooded ruthlessness deserves.

These efforts tapped into a current of popular anti-war sentiment, which could find no home in either of the major electoral parties. In turn, the fortunes of American socialism began to rise. According to data compiled by James Weinstein, the progressive historian and founding editor of In These Times magazine, the socialist vote in many American cities grew exponentially between 1916 and 1917: from 6.5 to 44 percent in Dayton, Ohio; from 4.5 to 22.4 percent in Cleveland; from 3.6 to 34.7 percent in Chicago; and so on. In New York City, socialist mayoral candidate Morris Hillquit drew crowds of more than 20,000 at Madison Square Garden, and secured an unprecedented 22 percent of the vote, despite—or because of—his controversial declaration that he would “not give a single dollar” for war bonds. In Dayton, meanwhile, the Socialist Party ticket (organized in part by the wonderfully-named Joseph Sharts) carried nine of the city’s twelve wards in the 1917 council primary, despite having spent only $395 on campaigns. At the time, the local papers admitted that disaffected voters who were “inimical to the war” had been the deciding factor.

In hindsight, of course, the socialists were entirely right. The First World War was a pointless, bloodsoaked disaster for everyone but the profiteers, and every ordinary American should have been resisting it. But under the Espionage Act, it was a crime to encourage “insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, [or] refusal of duty,” and Wilson’s government seized every opportunity to prosecute its opponents on those grounds. Eugene Debs, most famously, was convicted for his anti-conscription speeches under the Act, and imprisoned for more than two years. Undaunted, he ran for president from his cell, an option that may yet be open to Donald Trump. Charles Schenck took his case all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled unanimously that his pamphlets were not protected by the First Amendment, and upheld a sentence of six months’ jail time. (The Supreme Court being vicious bastards is one of the recurring themes of U.S. history.) One by one, the leaders of the anti-war movement were targeted, and taken down. Kate Richards O’Hare, one of the main organizers of the Socialist Party’s Committee on War and Militarism, was sentenced to five years in the Missouri State Penitentiary, and served two. Rose Pastor Stokes was sentenced to ten years, also in Missouri, simply for saying that “I am for the people and the government is for the profiteers” in a letter to the Kansas City Star. Victor Berger, America’s first socialist Congressman, was sentenced to 20 years, although he managed to have the verdict overturned. Emboldened by the Espionage Act’s broad scope, government agents raided 48 meeting halls of the Industrial Workers of the World, and put 101 of the union’s members on simultaneous trial. All were convicted of “conspiring to hinder the draft, encourage desertion, and intimidate others in connection with labor disputes,” including leader “Big” Bill Haywood, who fled to Russia rather than face 20 years’ imprisonment. In the space of a few short years, the Espionage Act decimated the ranks of the American left, which has never properly recovered its strength to pre-1917 levels. In doing so, it established a precedent that, in a nation that claims to care about freedom of speech and the press, citizens would never be entirely safe to make statements that clash with official war policy.

The Espionage Act reared its head again in 1951, with the trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg—the only Americans, so far, to lose their lives to its strictures. From 1940 to 1945, Julius Rosenberg had worked in engineering at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, where he was privy to scientific information about nuclear weapons (among other military technology.) According to government prosecutors, he had both passed that information to agents of the Soviet Union and recruited his brother-in-law David Greenglass—a machinist at Los Alamos—to do the same. In this way, both men were supposedly instrumental in helping the USSR gain their own atomic bomb in 1949. At the trial, Greenglass chose to cooperate with the prosecution, testifying that both Julius and Ethel Rosenberg had been part of a Soviet spy ring, along with Philadelphia chemist Harry Gold. In exchange for his services, Greenglass was given only a 15-year prison sentence. The Rosenbergs, by contrast, were issued the harshest sentence the Espionage Act allowed, and executed by the electric chair in 1953.

At first, it might not be clear why this was a miscarriage of justice. After all, the evidence we have today suggests that Julius Rosenberg, for his part, did give sensitive information to the USSR. His name appears in NKVD telegrams decrypted by the NSA’s Venona code-breaking project, and throughout the memoirs of Aleksandr Feklisov, a former Soviet intelligence officer who claimed to have served as Rosenberg’s handler. In this sense, it seems that Julius was guilty. However, there are complications. In the first place, the USSR was not actually an enemy of the United States during the years in question. On the contrary, it was a wartime ally up to 1945, the last year that Julius Rosenberg was employed at Fort Monmouth, and therefore had any secrets to give. Passing information to one’s allies without approval might be improper, but it hardly meets the Benedict Arnold definition of “espionage.” If it had been Britain or France involved, instead of Russia, it’s doubtful that anyone would have pursued a death penalty case, and there wouldn’t have been bloodcurdling cries to “fry the reds!” outside the courthouse. Only under the excessively broad language of the Espionage Act, which makes no distinction between friend and foe, can the Rosenbergs’ actions be considered a major crime, let alone a capital one.

Then, too, the significance of the information the Rosenberg ring provided has been greatly exaggerated. At the trial, Judge Irving Kaufman told the Rosenbergs that “I consider your crime worse than murder,” since “by your betrayal you undoubtedly have altered the course of history to the disadvantage of our country,” and even blamed the defendants for “the Communist aggression in [North] Korea,” arguing that it would never have taken place if the USSR hadn’t gotten hold of nuclear weapons. (Never mind that the “aggression” in question was carried out by Koreans themselves, and by China, which didn’t successfully test an atomic bomb until 1964. Coming at the height of the Red Scare, this sort of incoherent nonsense was rarely questioned.) At the time, no less a figure than Albert Einstein “ridiculed the notion that the accused and the informer against them could have understood or conveyed atomic information” that would actually be useful, and campaigned for the Rosenbergs’ release. And in any case, the USSR already had access to captured scientists from Nazi Germany through their Osoaviakhim program, just as the U.S. did through the notorious Operation Paperclip. They would have built an atomic bomb in any case; the only question was precisely when. The idea that “the course of history” hinged on the Rosenbergs’ actions was always a ludicrous one, and the death penalty they received under the Espionage Act was completely disproportionate. Political retribution, not justice, was the order of the day.

Worst of all, it seems likely that Ethel Rosenberg was entirely innocent, just as she had insisted throughout the trial. In 2001, David Greenglass admitted that he had lied on the witness stand; to the best of his memory, it was actually his wife, and not his sister, Ethel, who had typed his notes for transmission to Russia. Without this testimony, there would be no concrete evidence whatsoever of Ethel Rosenberg’s involvement in espionage—only the sexist assumption that, as Julius’ wife, she must have followed along in whatever he did. At most, she may have known in a general sense what her husband was doing, but chose not to turn him in. Under the doctrine of spousal privilege, this is not a crime. Still, it was enough to condemn her to death, and to make orphans of her two sons, Michael and Robert. Now septuagenarians, the Rosenberg brothers’ entire lives have been shaped by the shock of losing their parents, and the ongoing campaign to exonerate their mother. These are the real human traumas the Espionage Act leaves behind when it’s put into practice—and aside from the discretion of America’s judges and prosecutors, there’s nothing to stop such abhorrent sentences from being handed down again.

Thankfully, there’s never been another death penalty case under the Espionage Act. But successive administrations have used it to launch blatantly unfair prosecutions against their political enemies. In 1971, just 20 years after the Rosenbergs’ trial, Daniel Ellsberg came forward as the source who had leaked the Pentagon Papers to the world, and was immediately slapped with criminal charges. Two years earlier, Ellsberg had secretly copied the Papers—known formally as the History of U.S. Decision-making in Vietnam, 1945-1968—and given them to the press. He revealed how U.S. leaders had been lying about the war in Vietnam for decades, and how Richard Nixon in particular was willing to prolong the bloodshed indefinitely rather than admit defeat. Today, historians believe Ellsberg’s actions were instrumental in finally ending the war, and in toppling Nixon’s administration. Certainly Nixon himself viewed Ellsberg as a personal enemy, insisting that “We’ve gotta get this son of a bitch” behind closed doors. Facing 15 counts under the Espionage Act and other related statutes, Ellsberg could have been sentenced to 105 years in federal prison—and for a moment, it looked very much as if he would. His own defense lawyer, Leonard Boudin, admitted that “Copying seven thousand pages of top secret documents and giving them to the New York Times has a bad ring to it,” and Ellsberg himself fully expected that his children would “see me brought into the visitors’ booth in handcuffs” for the rest of his life. Ironically, it was Nixon’s hubris that saved the day. Ellsberg’s first trial, in 1972, was halted after it became clear that the government had wiretapped private conversations between one of the defendants and his legal counsel. His second, in 1973, had to be thrown out entirely after Nixon’s accomplices G. Gordon Liddy and Howard Hunt were caught breaking into Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office to look for damaging information about him. Still, it’s frightening how close the prosecution came to locking up one of the most important anti-war activists in American history, and throwing away the key. Under the twisted morality of the Espionage Act, revealing deceit and atrocity at the highest levels of government is a worse crime than actually perpetrating them.

If you told a room full of liberals that the closest spiritual successor to Nixon, in matters of national security, was Barack Obama, you’d get a chorus of sputtering, red-faced objections. But if you look at the way both men utilized the Espionage Act, the conclusion is hard to escape. Obama was a president with more secrets than most, from his use of drone strikes on American citizens to his expansion of warrantless wiretapping programs, and he showed a Nixonian ruthlessness when anyone dared to expose his actions to public scrutiny. In the 2010s, two whistleblowers came forward to do exactly that: first Chelsea Manning, who provided thousands of documents about the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan to WikiLeaks, and then Edward Snowden, who revealed the full extent of the NSA’s spying on Americans’ phone and internet activity. Together, they shattered the public perception of the so-called intelligence community and ushered in a new era of skepticism about state power. The illegality of their actions was far outweighed by the clear public interest in having the facts reported—but for their trouble, they were hit with the full power of the Espionage Act by Obama’s administration. Snowden was quite literally hounded to the ends of the Earth, and wound up trapped in Russia when the United States abruptly revoked his passport as he attempted to seek political asylum in Ecuador. When Manning voluntarily turned herself in, her sentence was particularly cruel, as she was given 35 years in a men’s prison, where she attempted suicide at least once. As Oren Nimni pointed out at the time, that’s a far harsher sentence than anyone ever got for torturing Iraqi prisoners, just one of the crimes Manning exposed. The fact that Obama eventually bowed to public pressure, and commuted Manning’s sentence, is no excuse. He did no such thing for Snowden, who is still in exile, and he was instrumental in preparing 17 Espionage Act charges against WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange for simply publishing the information Snowden gave him. In this way, Obama’s actions led directly to Assange’s own solitary confinement in Belmarsh Prison, the “British Guantánamo,” where his physical and mental health have suffered dramatically. In more recent years, Donald Trump’s administration carried on the persecution of whistleblowers by indicting Daniel Hale and Reality Winner under the Espionage Act. Much has been made of the irony, now that Trump faces Espionage Act charges himself. But it was Obama who paved the way.

It may seem strange to mention Trump in the same breath as Snowden, Manning, and Assange, but there’s an argument to be made that their cases are not entirely dissimilar. All of them involve information that would be firmly within the public interest, but which is forbidden under the Espionage Act to disclose. Looking back at the recently released recordings from Mar-a-Lago, it seems that the most obvious instance of The Donald sharing secret information with someone he oughtn’t came in the following exchange, where he complains about General Mark Milley and other “bad, sick people” from his former administration:

Trump

Well with Milley, uh—let me see that, I’ll show you an example. He said that I wanted to attack Iran. Isn’t it amazing to have a big pile of papers? This thing just came up. Look, this was him! They presented me this, this is off the record, but they presented me this. This was him, this was the defense department and him.

Staffer

Wow.

Trump

We looked at some—this was him, this wasn’t done by me, this was him. All sorts of stuff, pages long. […] I was just thinking, because we were talking about him, and you know he said “He wanted to attack Iran,” and what?

Staffer

He said you did?

Trump

These are the papers. This was done by the military, and given to me.

Predictably, most of the media attention to these recordings has centered around the moment when Trump admits that “this is secret information,” and that “As president I could have declassified it. Now I can’t.” Almost nobody seems to be paying attention to the substance of what Trump was talking about. In these moments, he essentially took an unnamed staffer aside, pointed to a document about a secret plan to attack Iran, and said “look, isn’t this crazy?” And maybe I’m naïve, but if my government—the one that ostensibly answers to me as a voter—is planning to attack Iran, I’d like to know about that, and have a public discussion about whether or not they should. Instead, by prosecuting Trump under the Espionage Act, the government is shooting the messenger. It’s reinforcing the idea that we, as citizens, have no right to know about such things until the bombs have already started to fall.

All of this is especially galling because, if the goal is to hold Trump accountable for his crimes, there are dozens of other opportunities to do so. Personally, I think the Georgia election-interference case is actually the strongest, since Trump was caught on tape demanding that Georgia’s secretary of state “find 11,780 votes” and overturn the 2020 election. Evidence doesn’t get more cut-and-dried than that. There are other charges that could be brought using the testimony from the January 6 hearings, which certainly seemed to indicate Trump’s willingness to hang back and see how a coup attempt played out before taking any action. If you were really serious about the pursuit of justice, you could even prosecute Trump on humanitarian grounds, and send him to the International Criminal Court. As Jeremy Scahill notes in The Intercept, he ordered the assassination of an Iranian general, a blatantly illegal act, and provided millions of dollars in material aid to Saudi Arabia’s genocidal war in Yemen, causing untold human suffering in the process. But Joe Biden’s government can never touch these more serious crimes, because it has committed similar ones itself.

Instead, we’re left with an Espionage Act indictment. In a best-case scenario, it may end Donald Trump’s political career. But this would be, at most, a Pyrrhic victory. The Act itself would remain a constant threat to news outlets, political organizers, and anyone else who stands in the way of American militarism and the surveillance state. The act of journalism would still be a criminal offense, if it happens to overlap with a subject the government particularly wants to keep secret. The First Amendment would still be a hollow shell, rather than a real protection, and future Debses and Ellsbergs could still end up behind bars. By dragging out this relic of the First World War, the state is making its priorities painfully clear. It’s sending the message that an American president can run roughshod over democracy and human rights all he wants, and face no consequence. It’s only when he runs afoul of the national security apparatus that he’s in real trouble.

Correction: This article has been updated to reflect the fact that Edward Snowden did not intentionally flee to Russia but was trapped there on a layover on his way to Ecuador. Thanks to reader Daniel F. for pointing this out.