How the Life Coaching Industry Sells Pseudo-Solutions to Our Deepest Problems

The cultural pressures to become a self-made individual have intensified at the same time that sources of social support have decreased. Enter the life coach.

Coaching is a $2.85 billion industry where anyone with enough chutzpah can hang out a shingle, even a virtual one, and offer their services for a fee. Take Alyse Parker, a 29-year-old attractive blonde social media influencer whose Instagram site features photos of her blissfully smiling in a skimpy green bikini in front of a retro orange VW bus on a Hawaiian beach. Parker’s life coaching business charges $5,700 for six months of services. She brands herself a “Mindset Coach.” Her YouTube videos include such fluffy titles as “The Ultimate Guide to Manifestation,” “Five Ways to Level Up Your Life,” and “My Views On Money.” In the latter video, she advises her some 670,000 followers to see money as “merely a form of energetic exchange” and that the secret to making a lot of it is “the energy you infuse into it.”

Long before the viral mania potential of the YouTube- and Instagram-fueled influencer economy, in the days of ’80s TV infomercials, charismatic life advice giver and part canvas-tent revival preacher Tony Robbins became the world’s most famous coach. Robbins never attended college and holds no professional training certifications, yet millions of people continue to flock to his auditorium-packed seminars and have bought his books. Under Robbins’ supervision, Oprah Winfrey fire-walked across hot coals, a stunt which landed Robbins his own (very short-lived) reality TV series. (The outcomes were not always so positive. After one Dallas firewalking session, five people had to be hospitalized, and 20 people were treated on-site for burns.) Even Bill Clinton and Donald Trump have footed the bill for Robbins’ high-end coaching.

So, what are Tony Robbins’ coaching credentials based on? Challenging life experiences. In his seminars, Robbins retells a “self-made” story. He pulled himself out of poverty, had a stint of homelessness, survived an abusive and alcoholic mother and pituitary brain tumor, and eventually worked his way up the motivational speaker ladder. Just as in the Horatio Alger novel Tony the Tramp (in which the title tramp molds himself into the Hon. Anthony Middleton, of Middleton Hall), Robbins’ lucky break also came when a wealthy older gentleman, motivational speaker Jim Rohn, took on Robbins as his mentee and personal assistant.

The Robbins coaching formula is simple. If Robbins was able to face his fears and overcome such challenges, so can you. Victims are self-made losers. Poverty, trauma, abuse, and life-threatening illnesses can be reframed as badges of honor—opportunities to transmute life’s lemons so one can become a winner. As Robbins writes in Awaken the Giant Within:

Through it all, I’ve continued to recognize the power individuals have to change virtually anything and everything in their lives in an instant. I’ve learned that the resources we need to turn our dreams into reality are within us, merely waiting for the day when we decide to wake up and claim our birthright.

Robbins charges $7,995 for his six-day “Date with Destiny” course, which came under the scrutiny of a four-part 2018 BuzzFeed News investigation. Given his grueling schedule of keeping participants awake until 2 a.m., a number of them became mentally unstable due to a lack of sleep, hydration, and food. In addition, the investigation uncovered numerous accusations of verbal and sexual abuse—from Robbins berating and screaming at a rape victim, to summoning a personal assistant to come into the bathroom of his hotel room where he was naked after coming out of the shower, to whispering in the ear of another staffer, “I wanna see you have an orgasm,” along with a class-action lawsuit settlement by volunteers for unpaid hours.

Coaching immediately conjures up the realm of sports and gamesmanship with clear winners and losers. Dale Carnegie’s best-selling self-help book How to Win Friends and Influence People not only had a major influence on Robbins, but also Donald Trump. When winning is the name of the game in a cutthroat competitive marketplace, it’s no wonder coaching has caught on like wildfire.

Celebrities like Robbins, along with the new generation of social media influencers such as Alyse Parker, Marie Forleo, and Jay Shetty, are in the elite class of mass media coaches. Despite the fact that media star coaching advice amounts to a hodgepodge of vacuous pep talk affirmations, their massive global influence cannot be ignored. Robbins is fond of telling his audiences: “Success is doing what you want to do, when you want, where you want, with whom you want, as much as you want.” With over 800,000 YouTube subscribers, self-help advice book author Marie Forleo assures her viewers and Twitter followers that “success doesn’t come from what you do occasionally, it comes from what you do consistently.”

At the top of the mass media heap, with 26 million Facebook followers and 7 billion video views, Jay Shetty tells his fans, “The biggest room in the world is the room for self-improvement.” And for a meager sum of $7,000, you too can become a life coach by enrolling in the Jay Shetty Certification School. In an introductory marketing video, Shetty spouts that his vision is to “transform 1 billion lives” through the ripple effect of his certification school. Shetty is a millennial Deepak Chopra 2.0. Capitalizing on his cultural appropriation of Indian Vedic philosophy, and by milking the cachet of his brief stint as Hare Krishna novice monk, Shetty has monetized his so-called “viral wisdom.” His success is 90 percent high-powered social media marketing, and 10 percent message—and even the piddly drivel he delivers has been called out as repurposed content from others he fails to quote, give credit, or accurately attribute.

Such mass appeal and insatiable demand for personal development resonates with a cultural ideology of unrestricted self-development. Robbins preaches a gospel of “Constant Never-Ending Improvement,” a coaching tenet tied to a nonstop treadmill of perpetually having to become a better version of oneself. If you’re not moving forward towards the ever-elusive improvement zone, you must be either lazy or a failure.

Completely unregulated, the coaching industry landscape looks like the Wild West. There are executive, leadership, business, team, and career coaches. One can also hire a wellness, nutrition, athletic performance, intimacy, or parenting coach. Then there are the fringe self-help guru coaches for manifestation, aura enhancement, shamanism, meditation, and spiritual development. The life coaching industry is thriving, with over 99,000 life coaches worldwide. Even coaching certification programs have become their own cottage industry. As reported in The Guardian, Brooke Castillo’s “Life Coach School” raked in $37 million in gross revenues during the first year of the pandemic.

There are no regulated government boards of examiners as there are for licensing psychotherapists, psychiatrists, and physicians. Claiming to be the “gold standard” for the industry, the International Coaching Federation (ICF) is self-regulated and has no legal authority or government oversight for enforcing codes of conduct. According to the ICF, coaches in the United States charge on average $272 for a one-hour session, while a seasoned Executive Coach commands $450 per hour. With just 60 hours of training, one can receive an “Associate Coach” certification, and 125 hours of training will buy you the title of “Professional Certified” coach. That’s an awfully good deal considering a full-time undergraduate college student puts in 225 hours in just one academic semester, or the equivalent of 1,800 hours for a Bachelor’s degree, and can come away saddled with student debt. Krista Kathleen earned her ICF professional coach certification and now offers a three-day life coaching course which includes vision boards, yoga, and astrology, along with ecstatic dance sessions for the bargain price of $1,000.

Googling the term “life coach” results in 1.3 billion hits, yet there is still no definitive consensus or body of knowledge that guides coaching practices. A cadre of social science academics have made research careers lamenting how the coaching industry is still not yet a legitimate profession. In their 65-year retrospective on the coaching industry, professors Anthony Grant and Michael Cavanagh at the University of Sydney write:

At present, the coaching industry is far from meeting the basic requirements of a true profession. … While individual coaching organizations have developed accreditation systems and codes of ethics for their own members, coaching as an industry does not adequately meet any of these criteria. … All of the key criteria for professionalization of the industry rely, at some level, on the development of a shared body of applied knowledge that forms the foundation of coaching.

It is no coincidence that the life coaching industry’s rapid growth spurt began after the 2008 financial crisis. During the recession, many displaced college-educated workers, out of desperation, scurried to reinvent themselves as independent contractors. Life coaching was seemingly an attractive opportunity.

There is, however, a fair amount of hand-wringing among life coaches regarding the shadiness and scammy nature of their industry. Olga Reinholdt is embarrassed to even self-identify as a life coach. Her blog post describes the complete absurdity and cult-like training which she and many other life coaches have been taught. Many training programs abide by a set of axioms dictating that coaches can never consult, never offer subject-matter expertise, and should never take the lead or make assumptions about their clients. The coach is to only ask questions, offer simple reflections, and “hold space for the client’s greatness,” which sounds more like a standard New Age workshop cliché. Reinholdt believes this dumbed down, formulaic curriculum is a ”fool-proof” strategy for training coaches that can be easily sold and marketed.

Her insider critique does not appear to be merely anecdotal. Based on 50 in-depth interviews with life coaches and their clients in Israel, the sociologist Michal Pagis describes the coaching process as one that enacts an extreme delegation of personal responsibility back on to the client, where the coach “steps aside” in order to function essentially as a “shapeshifter” mirror, forcing the client to find their own answers. This coaching technique is a bastardization of the “active listening” techniques in person-centered therapy developed by the late psychologist Carl Rogers.

The practice of life coaching, however, appears to be bipolar. At the other end of the spectrum are life coaches who are all too eager to dish out advice. In an open letter of confession, Jason Connell, now a licensed therapist, bemoans how it’s common practice among life coaches to be overly directive and have no qualms in telling their client what they should do. As a former successful industry insider and frequently invited speaker at elite coaching conferences, Connell describes how life coaches overestimate their competencies and “don’t fully understand that they are providing mental health services.” A popular (and grossly oversimplified) rule of thumb in the industry is that therapy focuses on the past, whereas coaching focuses on the client’s future. Yet, as the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s undercover investigation also revealed, it’s not at all uncommon to find life coaches overstepping their bounds and promising to “help” clients overcome their anxiety, depression, traumas, and addiction—and to even get them off their meds. Connell cites a litany of harms that overzealous advice-giving coaches have inflicted on their clients: instructing a rape victim to confront her perpetrator; bullying a client to share deeply vulnerable parts of themselves at a public seminar; assigning a client who suffered sexual abuse as a child a set of complicated affirmations; pushing clients to take “massive actions” and engage in risky decisions during times of major life transitions. The list goes on.

One way of putting lipstick on a pig to shore up legitimacy is to deliver coaching services via a luxury website and glitzy mobile app. Googling “life coach” produces a sponsored ad by the company BetterUp®. The search engine optimization tagline reads “Life Coaching That’s Personal: Get Matched With a Coach Now.” BetterUp is a San Francisco start-up that fuses the algorithmic tech and marketing power of Silicon Valley with a massive pool of virtual coaches available on demand. Not unlike the Tinder dating app, BetterUp makes access to a virtual coach just a couple of clicks away. Consumers respond to a few simple survey questions and BetterUp’s proprietary AI algorithm spits out nine potential coaches to choose from, each with their own snazzy cameo videos.

Having raised $300 million in Series E venture capital funding in October 2021, BetterUp’s $4.7 billion valuation makes this start-up the 800-pound gorilla of the coaching industry. And with an impressive investor portfolio supporting it, BetterUp has been able to assemble an amalgamation of Silicon Valley tech entrepreneurs, savvy social media marketers, and corporate salespeople, along with a small army of software engineers working on the back end. BetterUp’s online global reach extends to some 100 countries, with virtual coaching offered in 50 languages and offices in Munich and London. In addition, BetterUp targets its scalable digital executive coaching services to companies with more than 10,000 employees, including Big Tech cartel firms such as Google, Facebook, Airbnb, and LinkedIn.

Sophisticated digital marketing funnels are skillfully delivered to lure in those who want to become the best versions of themselves—whatever that means. Like any good marketing funnel, BetterUp’s platform first entices potential customers with educational messaging content with the intention of stoking more interest. Snappy video tips are delivered as livestreams—for example, BetterUp now offers a quick and dirty “building a one-minute Inner Work® habit.” This mindless content is reminiscent of the 1980s bestseller The One Minute Manager, with an Instagram makeover. The animated mannerisms of the video hosts resemble zesty Zumba aerobics instructors coupled with small-town TV weather forecasters.

Once the first click is had, the teasers begin. High production quality testimonial videos follow satisfied customers who have, of course, Bettered Up! It’s strategically targeted to a Gen Z and Millennial-diversity demographic, but there are also a few photogenic white women with ethereal glowing smiles who have, one supposes, found their authentic selves. Further seduced, one moves down the funnel, clicking through a series of query pages with multiple choice responses. This is the “getting to know you” data-gathering phase—where BetterUp’s proprietary algorithm does its matchmaking magic. “In what way would you like a coach to help you?” “How are you feeling?” “Are you ready to invest the time it takes to get the most out of your experience?” “Which coaching style works best for you?”

After the system has snatched your own demographic information and email, “It’s time to pick your coach!” So, who are BetterUp’s “highly qualified” coaches? BetterUp boasts that it contracts with only nine percent of those who apply to be in their global pool of some 3,000-plus coaches. Many of BetterUp’s coaches (independent contractors) are former business school and psychology graduates; others come out of finance, sales, and marketing, all of whom have forged second careers by becoming “certified” by, you guessed it, the International Coaching Federation. And now BetterUp has partnered up with ICF to conduct “cutting-edge” research to advance the field of coaching.

Not only has BetterUp used its VC-funded financial war chest to deploy the best predatory social media marketing and business development drones they can find, but Alexi Robichaux, BetterUp’s CEO, also enticed Prince Harry into serving as their “Chief Impact Officer.” His celebrity status, huge media platform, and mental health advocacy was a business synergy Robichaux couldn’t pass up. In one of their onstage bromance appearances, after giving Prince Harry a big hug, Robichaux tells the starstruck audience that his real concern for BetterUp “wasn’t about the business, it wasn’t about the customers, it wasn’t about the market, it was actually about the world and how society views the role of mental health.” Robichaux was in “search of luminaries in the world” who care about mental health, and meeting Prince Harry “was a no-brainer.” It’s curious that BetterUp describes itself as “the inventor of virtual coaching and the largest mental health and coaching startup in the world,” yet BetterUp does not offer mental health counseling with licensed therapists.

To provide a sciencey veneer to its coaching services, BetterUp has also recruited academic superstars—elite professors with New York Times bestsellers, viral Ted Talks, thousands of Instagram followers, and stellar reputations. BetterUp’s most prominent academic hired gun is professor Martin E. P. Seligman, founder of the Positive Psychology Center at the University of Pennsylvania, who has served as a member of BetterUp’s Science Board of Advisers since 2018. Given the anything-goes nature of coaching practices, Seligman’s stature as the “father of positive psychology” and former President of the American Psychological Association (APA) is a brilliant strategic merger, where slick marketing meets Pollyanna science.

“I’ve tried many different ways in my lifetime of spreading the science (of positive psychology), and BetterUp is the single best substantiation of my life’s work in the world,” is Seligman’s testimonial appearing on BetterUp’s website page for recruiting coaches. Seligman has built nothing short of a positive psychology commercial empire around him with books, apps, courses, and consultancy and training workshops (his fee for a single speaking engagement can be upwards of $50,000). But it’s Seligman’s academic respectability, derived from his relentless branding of positive psychology, that allows BetterUp to distance itself from the flashy, charismatic social media influencers and fringe New Age manifestation coaches.

Ever since his presidential inaugural speech to the APA meeting in 1988, Seligman has been like a dog with a bone evangelizing the superiority of positive psychology—with its supposed backing of scientific rigor—going so far in his speech and other subsequent writings to outright dismiss psychological approaches that came before his reign. Helping people who suffer from trauma and depression, writes Seligman, “can be a drag.” In preparing for his speech, Seligman recollects:

Psychology now seemed half-baked to me. The half that was fully-baked was devoted to suffering, victims, mental illness, and trauma. Psychology had worked steadily and with considerable success for fifty years on the pathologies that disable the good life, which make life not worth living.

Positive psychology is perfectly compatible with life coaching because the focus is on future-oriented achievement, success, resilience, and performance, not on negativity, misery and disabling pathologies. Remember, positive coaching psychology is about helping those who are willing to take personal responsibility—would-be winners—not the losers and whiners wallowing in negativity, those prone to complain about their oppressive social conditions or less-than-fortunate circumstances. So-called victims just haven’t learned how to become more optimistic and resilient. Seligman has even gone so far as to claim that depression is episodic and that by practicing some of his simple exercises, such as the “Gratitude Visit” and the “What-Went-Well” exercise, you can “raise your well-being and lower your depression.” All a depressed or traumatized person has to do is to learn how to “not focus on the negative” and simply look more at the bright side of things.

This “smile-or-die” psychology didn’t sit right with late investigative journalist Barbara Ehrenreich, author of the now classic book, Bright-Sided. Besides describing her contentious encounter with an evasive Seligman as she trailed him around the Philadelphia Museum of Art in an attempt at an interview, Ehrenreich, who earned a doctorate in cell biology, meticulously scrutinized the so-called “evidence-based” positive psychology findings hyped in the media. The widely touted and exaggerated claims in the field of “happiness science”—that positive disposition significantly influences longevity, health, immune function, and, of course, career success—were based on studies plagued by serious flaws, including inconclusive and mixed results, numerous methodological weaknesses, and positive reporting biases. “Most of these studies,” Ehrenreich writes, “only establish correlations and tell us nothing about causality: Are people healthy because they’re happy or happy because they’re healthy?” Even the longitudinal studies often cited frequently by positive psychologists that could shed light on these questions, Ehrenreich notes, are “not exactly airtight.” Ehrenreich’s exposé opened the floodgates. Other reputable scholars suspicious of this positive spin doctoring, such as Barbara Held, James Coyne, Edgar Cabanas, Nicholas Brown, and Harris Friedman, corroborated her assessment that the scientific veracity of positive psychology was more hot air and marketing puffery.

Resilience, mental fitness, and positive emotions—essential concepts in a life coach’s tool kit—sound so positive that one would think these fundamentals were discovered from studies of optimistic individuals. But that’s not the case. Early in his career as an experimental psychologist, Seligman conducted laboratory experiments on mongrel dogs and cage-raised beagles—for the advancement of science, of course. The first dog hung restrained in a hammock-like harness and was administered a series of inescapable, six-milliampere electric shocks via brass plate electrodes that were taped to footpads of the dog’s hind feet. The dog had no way to control or terminate the shocks. Twenty-four hours later, after a single “treatment,” the dog was placed inside a two-compartment cage called a shuttle box. By jumping over a low barrier separating the compartments, the dog could easily escape and thus avoid the shocks from the electrified metal floor. These preschocked dogs, however, failed to make the jump. They whimpered and lay down in the box, not even trying to escape. Because the initial shocks were uncontrollable, Seligman reasoned, the dog had no incentive to try to escape. Nothing it did mattered. It had learned helplessness. In contrast, a second dog was also strapped in the hammock but could escape the shocks by pressing against panels to either side of its head. When this dog was later placed in the shuttle box, it quickly escaped the shocks by jumping over the barrier.

Some 25 years later, Seligman published his book, Learned Optimism, which generalizes findings from the dog torture experiments to human beings: those who lack motivation and incentive to change do so because they have engaged in negative explanatory styles, telling themselves that bad things always happen to them, that nothing is within their control. They erroneously blame their problems on their circumstances. Like the preshocked dogs, these people have also learned to become helpless. As Seligman states:

I was stunned by the implications. If dogs could learn something as complex as the futility of their actions, here was an analogy to human helplessness, one that could be studied in the laboratory. Helplessness was all around us—from the urban poor to the newborn child to the despondent patient with his face to the wall. … It would take the next ten years of my life to prove to the scientific community that what afflicted those dogs was helplessness, and that helplessness could be learned, and therefore unlearned.

Looking through the lens of learned helplessness theory, quiet quitters resemble Seligman’s caged lab dogs: they passively “resigned” in the face of uncontrollable adversity. In one of BetterUp’s educational videos, employees rotting at their desks are, according to Seligman, “languishing,” which is described on BetterUp’s website as a “passive feeling of blah-ness that dulls your motivation.” These slackers haven’t fallen so far down that they can be considered mentally ill, but they’re not well, either (translation: fully productive). Rather, languishers are stuck in the massive middle ground, making them prime candidates for BetterUp’s coaching services. BetterUp cites its own questionable “study” showing that, even pre-pandemic, 55 percent of employees “at any given time are languishing.” In Human Resources lingo, languishing is also known as the “employee disengagement” problem, which poses a very real threat to corporate profit-making. On a global scale, this growth in worker discontentment amounts to $7.8 trillion in losses, or 11 percent of the global GDP. And since the pandemic, the trend has worsened. According to Gallup’s 2022 indicators, only 32 percent of employees in the U.S. report being actively engaged with their work.

BetterUp’s website is awash with corporate cheerleading chants: “Go from languishing to thriving!” “The BetterUp platform delivers transformative coaching experiences to drive productivity, engagement, and retention at scale.” “Today, mental health and well-being must be a top business priority because a thriving worker is an engaged, adaptive, and high-performing worker.” However, the “thrive, flourish and perform” coaching mantra extolled on employees assumes that mental health and well-being are completely determined by personal agency, so there is no need, as Seligman has argued, to consider whether their circumstance—such as poor working conditions, toxic corporate cultures, low wages, bad bosses, unrealistic job demands, a lack of health insurance and stable employment, and meaningless work—might explain why employees have become demoralized, burned out, and disengaged in the first place.

Positive psychology’s compulsory optimism is contingent upon a denial and disowning of what Seligman would consider negative emotions, such as anger, anxiety, frustration, resentment, and sadness, which are supposedly mere impediments to mental well-being and human flourishing. Seligman’s “learned optimism” entails skillfully replacing negative feelings with positive ones, shrugging off setbacks or misfortunes by unlearning and rejecting anything smacking of pessimism. This demonization of the full range of human experience is a toxic positivity, a sickening, contemporary form of Pollyannaism. As the Ukrainian-born psychoanalyst Oksana Yakushko writes in her book, Scientific Pollyannaism: From Inquisition to Positive Psychology:

[T]he insistence on optimism and happiness as ideal states is viewed as reflective of cultural-political forms of social compliance, which requires denial of oppressive conditions and inequalities and which necessitates routine engagement in disassociation, disavowal, and splitting. These defenses are employed to maintain the individual insistence that, like Pollyanna, the person is always ‘glad for everything.’ Pollyanna is presented as a perpetually optimistic child, as someone who plays the ‘glad games’ no matter how much she suffers or what suffering she observes.

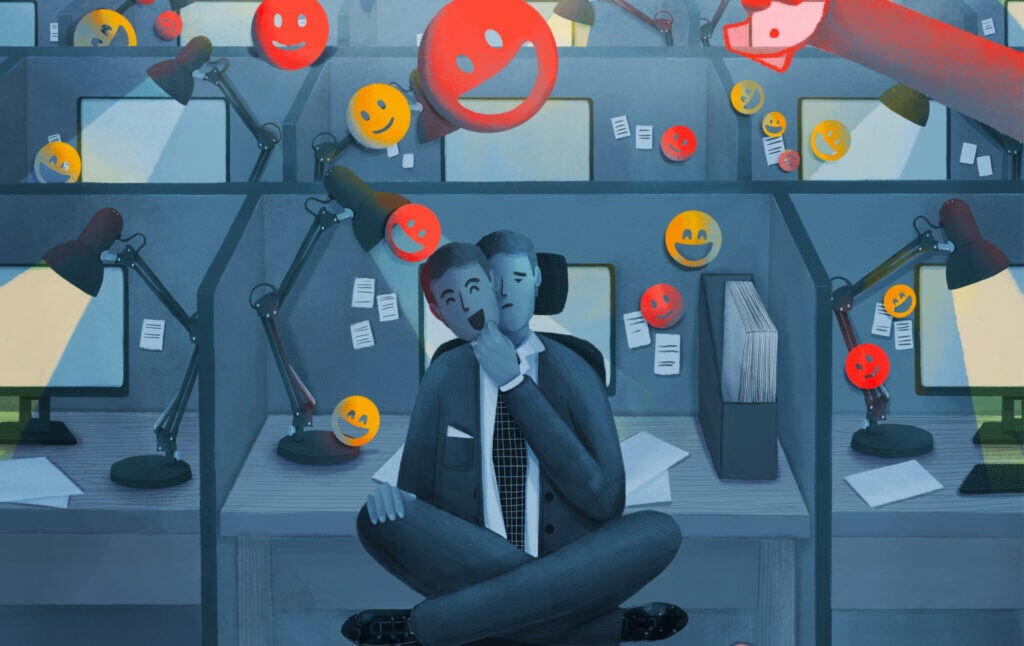

The peddling of toxic positivity is like a three-card trick. The first card shames the individual for feeling anything but positive emotions; the second, victim-blaming card insources responsibility for change on to the individual, inflating the amount of agency a person really has by downplaying the role of circumstances; the third card legitimizes the need for social compliance (via coaching), that is, to “better up” by learning to be more positive and mentally fit for corporate duty.

Pseudoscience “Happiness Formulas” and “Happiness Pie Charts” have been circulating among life coaches to persuade people that circumstances (such as race, age, sex, income, health, level of education, etc.) account for less than 10 percent of our happiness. For example, Seligman’s dubious equation (Happiness = S + C + V) asserts that 50 percent of our affect is a genetic disposition, or our “set point range” (S); some people are simply lucky to have been born with the smiley genes. Why bother with social activism, unionizing, or calling for systemic reform if circumstances (C) account for only 10 percent of your happiness? And money doesn’t buy you happiness—how convenient! If we are unhappy about being unemployed, losing our health insurance, and incurring massive debt through student loans, it is our responsibility to learn to be more positive and optimistic. This is where life coaching gets its traction: a whopping 40 percent of happiness is supposedly under our voluntary control (V).

Seligman’s positive psychology ideological agenda is conservative, corporate friendly, and more than willing to accommodate to the status quo. It’s of no coincidence that Seligman befriended the late Sir John Templeton, a right-wing, evangelical Christian and highly successful global investor and prominent donor to conservative groups and Republican candidates, and eventually received $2.2 million of philanthropic welfare from the Templeton Foundation for the flush funding of his Positive Psychology Center. And for all of Prince Harry’s Royal Commando talk about the need for “mental fitness” (another one of BetterUp’s signature coaching concepts), it’s actually Seligman’s brainchild—derived originally from the Penn Resiliency Program (PRP) and then adapted for application in the U.S. Army’s $125 million Comprehensive Soldier Fitness (CSF) program (Seligman’s Positive Psychology Center was awarded a $31 million “sole-source” contract by the U.S. Army). According to Seligman, the CSF program would “create a force as fit psychologically as it is physically,” or in Department of Defense parlance, would “optimize warrior performance.”

In fact, the CSF program was conceived as a psychological intervention that would “increase the number of soldiers who derive meaning and personal growth from their combat experiences.” Under Seligman’s supervision, his “train the trainer” program delivered skill-building modules in “master resilience training” and principles of positive psychology, cognitive restructuring, mindfulness, and self-regulation training to over 1 million soldiers. Not only did the CSF program ignore the moral injury to combatants, but it deliberately trained soldiers to temporarily override and cloak their negative emotions in the battlefield and to defer their pain and vulnerability to when they returned home. The program was discontinued due to its questionable evidence base, as well as ethical concerns voiced by the Coalition for an Ethical Psychology. A shadowy history also haunts Seligman’s contested association with military psychologists who were key architects of the CIA’s secret interrogation program, as well as his speaking engagements at the Navy’s Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) school.

Seligman certainly has good connections. BetterUp was awarded a sole-source contract by the Department of Defense to deliver its virtual coaching services to the U.S. Air Force and Space Force. Endorsing the coaching program, Lt. General Gina Grosso quips on a BetterUp promotional video that, “BetterUp provides an opportunity to put another tool in the tool kit that we don’t have today to ensure that we have the world’s greatest air and space force well into the future.”

In order for the cure on offer to be perceived as a legitimate solution, the diagnosis of the malady must be as well. The coaching industry has manufactured a regime of truth that a languishing labor force has a motivation deficit problem. But this is a grossly self-serving misdiagnosis. Something much more is going on culturally than simply a case of the white-collar blues and motivational doldrums. Are employees languishing, as Seligman would like us to believe, or is their resignation more a reflection of a widespread cultural malaise, as well as a sane response to the crisis of work itself in a “post-pandemic” society? Beginning with the 2008 financial crisis, the corporate demands to “do more, with less” were already wearing thin. Then came the collective pause of the COVID lockdown, which provided an unprecedented space of psychological distance for large swaths of the workforce who suddenly found themselves working remotely. This forced hibernation set in motion an unexpected sea change in mass soul-searching and values clarification, leading people to question the centrality and legitimacy of work itself. Going beyond the call of corporate duty at the expense of one’s health, well-being, and relationships no longer felt like it was worth the personal sacrifice.

With burnout levels soaring, turning to a life coach for help has become an appealing alternative to seeking a licensed mental health provider. The negative stigma associated with seeking a mental health professional has been a boon for the life coaching industry. Life coaching is upbeat and easy to access, and its framing as a positive brand for self-improvement involves less shame than seeing a therapist. People who are really needing professional help may be in denial about their untreated mental illness or deep-seated psychological problems. At the same time, it’s not uncommon for some coaches to be deceitful or to overpromise “results” or overstep their bounds by practicing therapy without being qualified or licensed to do so. As freelancers and entrepreneurs, life coaches have invested in internet marketing and attractive websites that make onboarding smooth and painless for potential customers. And despite the fact that life coaching is not covered by health insurance and is unaffordable ($272 on average for an hourly session) compared to seeing a licensed therapist, the coaching industry is booming.

Managed healthcare providers have created bureaucratic obstacle courses to accessing licensed mental health providers that even the insured are not willing to navigate. Some 85 million Americans lack adequate health insurance, and, according to a study by the National Council for Mental Wellbeing, 42 percent of the population views cost and poor insurance coverage as key obstacles to accessing mental health care. Senator Bernie Sanders is introducing legislation that will greatly increase the number of mental health providers and increase funding to community mental health clinics. That’s a commendable start, but what this country really needs is a universal, equitable, freely available mental health services system.

Finally, we must ask: why do people hire life coaches—paid strangers—in times of need? The cultural pressures to become a self-made individual have intensified at the same time that sources of social support that were once the domain of families, friends, churches, and other civic and fraternal organizations have dramatically weakened. In the midst of what has been characterized as a “loneliness epidemic” in American society, even friendship is being commodified and outsourced to the market. Founded by SoulCycle entrepreneur Elizabeth Cutler, Peoplehood is a new “social wellness” company offering a “connection product” that trains empathic “guides” to lead and facilitate “gathers.” Commodified friendship and life coaching are symptomatic offspring of a society driven by competitive individualism and plagued by social media comparisons and increasing isolation. This huckster culture propagates a doctrine of continuous self-betterment, quick fixes, and inward-looking makeover schemes while blinding us to the systemic and structural causes of distress and cultural malaise. We have lost stable social anchors, which leads to festering insecurities and personal anxieties. To forge a self-made identity, we are ever more reliant on experts and the faux intimacy of commodified service providers, which the life coach will cheerfully provide.