What ‘Economic Freedom’ Would Look Like

Economist Mark Paul explains why we need an ‘economic bill of rights’ and why the right-wing libertarian conception of ‘freedom’ is bananas and won’t actually make us free.

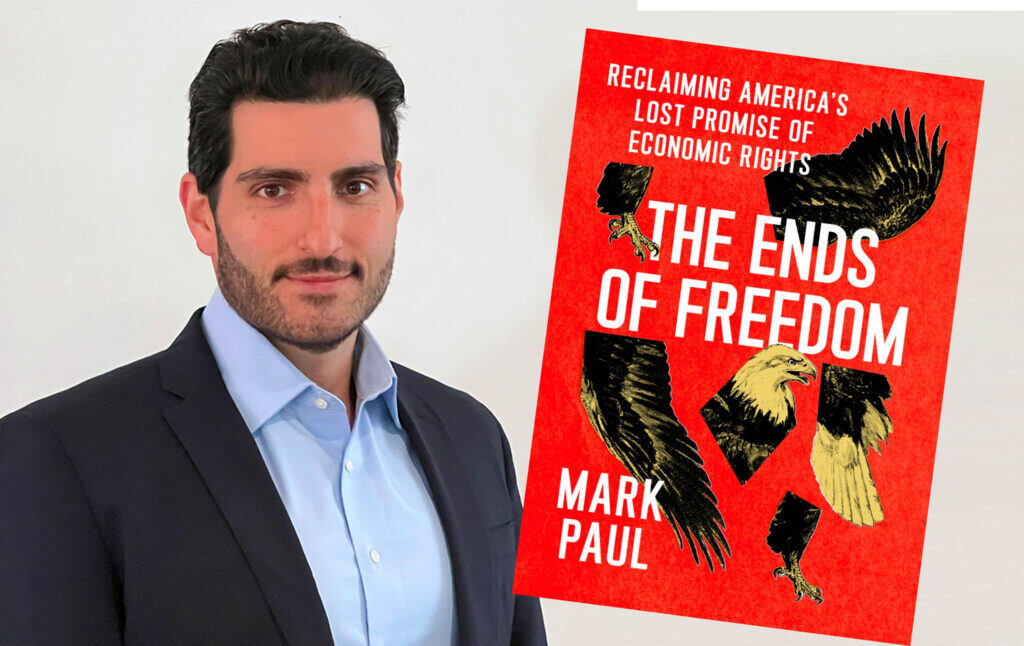

Mark Paul is an economist who argues that there can be no meaningful freedom without economic freedom—by which he does not mean the libertarian idea of the freedom to exploit others. Mark’s book The Ends of Freedom: Reclaiming America’s Lost Promise of Economic Rights explains how having a functional and free country will require establishing new rights: the right to employment, the right to housing, the right to healthcare, the right to a clean environment, etc. Today he joins us to explain how we can create a true “land of liberty.” This conversation originally appeared on the Current Affairs podcast and has been lightly edited for grammar and clarity.

Robinson

You open your book with an extended quote from the United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, who took a trip to the United States in 2017 and produced a report. His conclusion in that report was a little depressing, shall we say?

Paul

It sure was. Philip Alston came to the U.S. about five years ago now. He’s used to touring refugee camps, war torn countries, and developing nations that are still dealing with lack of clean water, sanitation, and things along these lines. What he saw in the U.S., unfortunately, baffled him; he saw people in the U.S. living in essentially public squalor amidst its abundance. I think what really caught him off guard was when he spent some time in Skid Row in Los Angeles, which is actually about a block away from where my office was last year when I was visiting at the University of Southern California. I think we had similar eye-opening experiences walking around Los Angeles—the city of dreams and angels, of course—and seeing people lacking basic access to toilets, food, and anywhere to sleep at night. It really struck him, and I think should strike each one of us, that we are living in this extremely wealthy country, yet we have 40 million of our fellow Americans in absolute poverty.

Robinson

Yes, I think that does strike plenty of people. The contrast is very obvious. People walk around and see it—you really can’t miss it. But from the book I feel like one of the things that strikes you in particular when you see this, as an economist, is that you look at this as being avoidable. This isn’t necessary. This is a country shooting itself in the foot, and is all completely preventable.

Paul

That’s right. Not only is poverty an individual crisis, it’s a public calamity for so many reasons. As an economist, I have to think about all the lost productivity we have from the fact that our fellow humans, our fellow community members, certainly aren’t engaging in very productive activity because they’re worried about where they’re going to sleep at night and their next meal will come from. Often we think that’s unfortunate for the individual, but the thing is we’re part of a society, we’re part of a community, and we can’t think that way. Just because individuals are poor doesn’t mean that they’re the only ones negatively affected. We’re all poorer for it. Think about all the people that could have been nurses, teachers, restaurant servers, or every other single profession. Instead, these people are just struggling to figure out how they’re going to survive the night, and it’s just a huge drag on the economy. It’s essentially akin to dropping anchor and wondering why your ships moving so slowly, when we’re talking about poverty here in the U.S.

Robinson

You ask these important questions about our definition of freedom. Your book is called The Ends of Freedom, and freedom is the heart of what you’re writing about in it, and about this distinction between negative and positive rights. So, it’s not just “We could be growing the economy here, we could be more productive.” If we take freedom seriously, and actually want to guarantee it to people, you ask important questions, like:

- What is the value of a constitutional prohibition on laws abridging free speech to the residents of Skid Row who can’t access a toilet?

- What good is the right to vote for a person who’s too sick or lacking time off work to get to the polls?

It not only means that we have so much potential that we are not realizing, but it makes hollow what is supposedly the central ideal of the nation.

Paul

American freedom, at least in its hegemonic form, needs a serious rethink. Neoliberalism has promised us that as long as we have what we traditionally call negative freedom (freedom of limited government, freedom from coercion, and access to these mythical free markets), we will be doing just fine. But the reality has played out to be quite different from that. When we think about Jefferson’s promise of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, I think we can quickly realize that tens of millions of Americans continue to be denied those basic freedoms here today. Civil rights are one aspect of our political rights, but neither of those are enough. Nor are our reproductive rights, which are increasingly coming under attack across the United States with the strike down of Roe v. Wade by the Supreme Courts and the enactment of increasing restriction to reproductive care across the states, particularly in the South where you’re located.

And so, we need to stop being on defense and thinking about limiting the rollback of freedom and instead go on the offense and actually rethink what freedom means. What is meaningful freedom? And here is actually where I’m going to say I agree with Milton Friedman: I agree that freedom means actually being “free to choose” the type of life you lead, and being free to realize one’s dreams to a reasonable degree. Today, instead, we see people dreaming of going to college and graduating with $100,000 in debt. Rather than an education being a right, it’s a debt riddled privilege.

Freedom means taking away the fetters of debt and shitty bosses, and letting people actually live meaningful lives and providing them the ability to determine what that meaningful life is for themselves.

Robinson

We’ll use that quote: “Freedom means taking away the fetters of debt and shitty bosses.” I like that one. As you say, the problem is not with the values that someone like Milton Friedman endorses ostensibly, like with his famous TV series Free to Choose, based on his famous best-selling book, Capitalism and Freedom. Because being “free to choose” would be great. But under the economic system that he spent his life advocating and sometimes helping to impose on other countries, that kind of freedom to choose becomes a lie and a terrible fraud. Because when you ask if people are meaningfully free to choose, the answer is no. Their range of realistic options is quite constrained.

Paul

Yes, absolutely. What’s amazing about this is that neoliberalism fails on its own terms because it never meaningfully engages with the lack of freedom, where we spend most of our waking hours at work here. The idea from Elizabeth Anderson, I think, is really helpful. Her work on the lack of freedom, where we spend 45 hours a week at work—actually, in the U.S. it’s 47 hours a week on average–is something that we all need to contend with much more. Yes, we need to limit the course of powers of the government, but let’s talk about limiting the course of powers of the employer. That’s precisely why people need economic rights. We need to figure out how to detach basic economic security—ensuring we have food on the table and a roof over our head—from being subjected to the whims of a boss.

Robinson

Your book is very constructive because you don’t actually spend that long just identifying the serious dysfunctions in the United States today. You write, given these dysfunctions that everybody has talked about and noticed, and as we think about how to move ourselves towards some kind of solution, how do we think more clearly about what it is we actually want? What you offer is a comprehensive prescription to address the problem of persistent economic insecurity based on an expanded notion of American freedom, grounded in an alternative model of economic thought. You say the United States can, in fact, eradicate poverty and build an economy that works for everyone. Sketch for us the framework that you think that we need in our heads if we are going to start thinking about what we ought to do to fix all this.

Paul

I think we’ve all read more than a few books on why capitalism sucks. And so, when I set out to write this book, I wanted to write a little bit about why capitalism sucks, but what I really wanted to do is write about what could replace it. Much of this motivation actually came from my time at Occupy Wall Street, more than a decade ago now, where people had a slogan that they wanted the economy for the 99%. They didn’t exactly know what that meant, and that’s okay. We can have the broad vision and not know what the policy details look like yet. But as a policy economist, I figured I’d sit down and start thinking about this seriously and what the policy details might actually look like. What I uncovered in doing that actually is a lot of the radical history of progressive policy we have right here in the United States that we simply fail to talk about. In 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt actually introduced this idea of an economic bill of rights, which I build on in this book, which in Roosevelt’s term was the culmination of the New Deal. It was to provide a cradle to grant security for each and every person here in the US. Some of the cornerstones were things like the right to a well paying job, which, believe it or not, was part of the Democratic Party platform from 1944 all the way until 1988, when Gary Hart ran on his stump speech of the end of the New Deal when the Democrats finally took this out. Others include things like the right to housing and education.

Senator Sanders ran on this idea that health care is a right, not a privilege. As an economist, I flat out agree with him. There are some things that belong in markets. When I go to the grocery store, the market can help me decide if apples or bananas are in season, but when it comes to life-saving health care, the market really has absolutely no role to play and is something that we should decommodify. In the book, I lay out the policy prescriptions to achieve these economic rights, while simultaneously trying to uncover the long struggle for these various rights that we’ve had right here in the U.S. We can learn a lot from the social democracies like Finland and Denmark, both of which, by the way, have higher homeownership and economic mobility rates than the US does, despite the wonderful lies we tell ourselves about the US being one of the most mobile societies in the world. We can learn a lot from these countries, but I also think we can learn a lot from ourselves. We have such a rich history here.

Robinson

Harvey Kaye has been interviewed for Current Affairs a couple of times, and this is what he says. Stop talking about Finland, and start talking about Thomas Paine, Franklin Roosevelt. Go back and look at the great social democrats and socialists in American history, and all sorts of models that we have to build from here.

The economic rights that you’re talking about, like the right to a well paying job, are divided into chapters in your book. Part two of your book is economic rights. You have the right to work—by which you do not mean right to work legislation—the right to housing, the right to an education, the right to health care, the right to basic income and banking, and the right to a healthy environment. Let’s start with the right to work because people will have heard that phrase before—we have right to work laws in states across the country.

Paul

So, what’s funny about this is when you and I talk about right to work, we immediately think about the right of an employer to bust a union through open shop workplaces, and that’s what people are going to tell you if you talk to the D.C. wonk policy crowd. But when you go talk to your average Americans, and I did this—I actually did some fantastic polling with Data for Progress—we ask people, “What does the right to work mean to you?” and what the vast majority of people say it means the right to a well paying job at a decent wage. So, most Americans get the right to work, that anybody willing and able to work should have access to employment, and that no employment should pay anything below a living wage. It’s as simple as that.

Now, the policy to get there is a hair bit more complex, but it’s really not that big of a deal. In fact, there’s really three components that I write about, but when people tell me enacting something like this will be too complicated, I again like to look to history. Everybody has largely heard of the Works Progress Administration, but many people haven’t heard of its predecessor, which is the CWA. The CWA [the Civil Works Administration], which Roosevelt enacted with the help of Harry Hopkins, decided that, in the heyday of the Great Depression, they had to put people to work, fast. Within two months, they put 4 million Americans—one-tenth of the American workforce—to work doing public works projects, building schools, bridges, and canals. They even took up a garment factory that went out of business because consumers didn’t have any money to buy underwear, and knit long underwear for everyone—every single household in Michigan got a free pair. These are the types of things that they did.

Robinson

Underwear for all.

Paul

That’s right, long underwear for all. It’s cold up there in Michigan. So, we’ve done it before. What does the right to work look like today? Firstly, we need to keep running the economy hot. The Federal Reserve actually has a dual mandate, one of which is maximum employment, something that actually came out of Coretta Scott King’s long fight for full employment, and the second is that we need to massively expand our public employment sector. Here in the US, we employ about half as many people, accounting for population, in the public sector as does Germany and about a third as many as the Scandinavian countries. We could offer so many more helpful government services to lift people up and to improve our everyday lives. We just need to simply expand public employment. And the third is an actual job guarantee. This has been part of the American conversation for nearly a century now. It’s just the idea that we, as a federal government, should provide everybody a job that wants one, given that the private market will never provide true full employment.

Robinson

If people want jobs, they’re asking to contribute productively to do things that provide goods and services that people want or need. Unemployment is a very strange kind of squandering of human potential.

Paul

Joan Robinson said of Keynes, “He hated unemployment because it was stupid,” and I couldn’t agree more. Somebody wants to contribute to improving our society, and tell them they can’t. That’s basically what unemployment is. It’s just absolutely amazing. But why do we have unemployment? Capitalism necessitates that we have unemployment because, as the Polish economist Michał Kalecki likes to talk about, the bosses would rather have discipline in the factory than an economy running full steam ahead. The reason we have unemployment is that we need the threat of unemployment to always exist, or else that hierarchical top-down workplaces that we all know and hate wouldn’t be able to function to benefit the bosses.

Robinson

Yes, it would be a radically different world if no one really needed their particular job, and could at any point say, “I actually don’t need this job, I could go get a different one.”

Paul

That’s right. And this is what we’re starting to see right now with what’s starting to become a slightly tight labor market, by historic standards. Is 3.5 percent unemployment full employment? No, but we’re seeing workers switching jobs at higher rates than they used to, and it’s resulting in huge wage gains for the lowest income workers. It’s also resulting in better work conditions, with people moving away from just-in-time scheduling that absolutely screws workers, especially those with families. We’re seeing folks move into better, higher paying, more rewarding jobs, when they have the choice to. People don’t work in shitty jobs because they love flipping burgers at McDonald’s. People work in shitty jobs because it’s the only option they have available to them.

Robinson

Yes, expand the range of options so that people don’t have to take the shitty jobs. How do you feel about the term “labor shortage”? I always get so annoyed at the way the term is used because there are at least attempts to loosen the child labor laws now with employers claiming there’s a labor shortage. Have you tried doubling the pay on offer and seeing if there’s still a labor shortage?

Paul

Yes, just as Marx said, we always need a reserve army of unemployed, and the employers crying wolf over labor shortages is just them trying to figure out how to keep wages down and employees on their heels. The last thing they want is for employees to feel empowered. That’s when the authority of the bosses starts to get challenged, wages start to go up, and they start to see their profit share starting to fall. And that’s not what they want to see. Labor shortage is just class warfare, put into language that you can print on the front page of the Wall Street Journal.

Robinson

It’s very annoying to me because I see people who should know better repeating it. It seems we should be asking: What are you really saying? “I can’t find enough workers to accept the deal that I am currently offering”?

Paul

It’s fascinating to think about this in a dynamic sense, too. Let’s say they’re right for a second, give them the benefit of the doubt, and say we have a labor shortage, which is just not the case. We have many people who are currently unemployed that want jobs, and also have plenty of people who are out of the labor market that would like to come into it if they saw decent jobs available. If there were a real labor shortage in society, you might have been able to argue there was during World War II when unemployment was about 1.7%, half of what it is today—clearly, we have lots of room to run. Let’s just say, though, there was. Guess what? We would start automating some really low productivity jobs. Rather than having people flip burgers at McDonald’s, we would get rid of the shitty jobs that people don’t want and transition those people into better jobs. That’s what happens. If you have an actual labor shortage, we have higher productivity growth and workers transitioning to better jobs, and it’s a good thing. We shouldn’t want this as a society. This is how we evolve. Now, that’s not where we are, but nevertheless, we can’t think about the labor market as something frozen in time. People are constantly shifting from low productivity to high paid productivity jobs, and that is an advance for society.

Robinson

Yes, one of the absurdities or tragedies of the economy as we have it is that people have to fear automation, which is odd because automation should be exciting. It should be that now no human has to do this thing and we’re freeing them, but instead, we know that people will suffer if they lose their jobs because we don’t have fallbacks.

Paul

I wrote a report for the Roosevelt Institute a few years ago that we called “Don’t fear the robot, fear the policymakers”. Robots make us collectively richer. This comes back to a core argument in the book, which is that we have plenty to go around. Scarcity is something that we impose on individuals. There is no scarcity as a society at this point in our development; we have plenty of food, housing, and health care to go around. It’s true we might need to train more doctors, nurses, or teachers, but we have enough people to be able to do all those things. Scarcity is purely self-enforced through the policy process. The robots just keep making our lives easier. What we need to fear is when we use the robots as a way to keep the poor on Skid Row by telling them “Sorry, we don’t have any jobs for you,” rather than doing what the unions have been fighting for, for near a century now, which is that we engage in work sharing. We can reduce work hours.

Keynes told us in this beautiful essay, “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren“, that we’d all be working 15 hours a week right now. It sounds nice. Even some of the wealthier countries that are engaging in reducing work hours are dreaming of 35 hours, so we’re still pretty damn far from 15. But if we actually shared those gains equitably, we really could be working 15–20 hours a week and picking up whatever our hobbies are. People could be reading more Current Affairs issues while kicking up their feet at the promenade.

Robinson

Yes, we need more time for magazines. I’m totally in favor of any policy that encourages magazine leisure time. I do want to discuss at least one of these other rights that you write about in part two of the book. The right to an education is interesting because it strikes me that this is another area of just massively squandered human potential, where every obstacle to people learning stuff seems like an example of a society shooting itself in the foot.

Paul

Yes. The U.S. used to lead the world and college educational attainment, and today, we’ve dropped all the way down to 14. I think we can take a step back and ask, why is that? What’s going wrong? Are kids not wanting to go to college anymore? No, that’s not it. Is it that we’re not funding our public colleges and has become this debt riddled system of full of booby traps and other nasty things along the way, pushing people out at every single turn? Yes, that’s actually it. When you look at the data as to why people don’t go to or leave college, it’s because they can’t afford to stay, have to make money to put food on the table, and can’t take out enough debt to actually make ends meet when they’re in college. It’s things like this, and we’re all collectively poorer for it. By not training the American workforce, we’re losing out on a tremendous amount of economic growth.

But, people on the left often make these arguments that I’m making and say the economy would be bigger if only we invested in higher education or in prekindergarten. Those things are true, but we’re not playing the game of Monopoly here. We’re not just trying to make as much GDP growth for the hell of it. We’re also trying to live in a decent society where we recognize that education is a fundamental and essential part of our struggling democracy at this time. If we want to fight against fascism, education is a damn good place to start. So, by not investing in education, we’re not only slowing the economy, but I think we’re really further threatening the stability of our democracy.

Robinson

I hear people saying, Americans don’t know anything and can’t identify the three branches of government. I read in the paper yesterday that only 14 percent are proficient in civics or something. If you took seriously the idea that everyone has the right to an education and made sure that a quality education was provided to every person, then you’d start to see that people would know things because that’s what an education is.

Paul

We have to invest in one another as a community, and I think that’s exactly what we need to be doing. One interesting thing to note here is that we didn’t use to have access to free high school the way we all do today. I’m a product of public school systems K through Ph.D., but over 100 years ago, I might have been able to go through grammar school. Grassroots movements fought for and won access to free high school, and they deemed it necessary to be able to be a member of society in the early 20th century. And here we are today, in the beginning stages of the 21st century, and times have changed yet again. Our jobs require people to have a college degree. It’s estimated that by 2030, 71 percent of jobs will require a college degree, yet here we are with roughly 30 percent of Americans holding them. How do we close that gap? We provide people with free college.

Robinson

You mentioned that you went to public schools through your Ph.D. You studied economics at UMass Amherst, which has one of the few economics departments in the country that nourishes heterodoxy. People on the left often criticize economics, and it’s true that many of the criticisms of economics are valid in terms of mainstream economics. But there are economists, you among them, and I assume some of the professors that you studied under, who are trying to rework the economics profession and purge it of some of these ideological presuppositions that lead economists to be associated with disastrous, neoliberal policies.

Paul

Yes, I was lucky enough to get to go to UMass Amherst for both my undergrad and Ph.D. I actually took a brief detour out of high school and went to culinary school and worked for a few years. The 2008 financial crisis happened, and I was lucky enough to be from Massachusetts and have this somewhat radical alternative economics department in my backyard. Much of this was just luck—right time, right place. I thought I’d go back and get a bachelor’s degree, and next thing I knew I was hooked and couldn’t look away from economics. And really, it’s because of my time in the kitchen where I was working alongside fellow cooks on the line, and none of us could afford to go to dinner at the restaurant that we had all been cooking in. There’s no way I could have imagined paying $150 for a meal back in 2006. I was making $7-8 an hour back then, which, unfortunately, is today what people are still making at a lot of those jobs.

And so, that got me asking questions about the economy. At UMass, my professors, rather than asking how to maximize GDP, were thinking about how to improve the human condition. How do we make sure that each person has enough? How do we build an economy that works for the people rather than the corporations? I got a fantastic education there that helped me read the classic great thinkers like Keynes and Marx, and actually read Smith, rather than stealing one line on the “invisible hand” and saying, “This is all Smith ever said.” Smith was a brilliant and nuanced thinker that the right has very effectively and simply weaponized to tell their simple, magical, false story.

So, if you know people want to read economics, there’s a lot to learn there. It’s just the stuff we teach in modern day graduate schools is simply utter bullshit. I have to say we’re losing the fight within the profession, but I think we’re starting to win in the public domain. People get that neoclassical economics is garbage, and the policymakers are starting to get it, at least on half the aisle. The other half, I think, get it too. They just realized that it’s in their class interest to pretend otherwise in public. So, I do think that the economics and the public debate are changing in radical ways. The Biden presidency is an example of that. I think a lot of what President Biden has done was just completely unimaginable under Obama, and it’s because of the economics, actually.

Robinson

Every time I read a good thing on economics, the person is somehow associated with UMass. One of the things I like about people who are from UMass Amherst economics department is that you take the uplifting rhetoric about what we all deserve a right to, and you start to think through the math. There is this great paper on how to fund Medicare for All by Gerald Friedman at UMass Amherst. People ask, how are we going to pay for it? He says: here’s how. And this is what you do in the last part of your book, at the end of chapter 10. Once you’ve laid out all the things that we have a moral entitlement to and how they improve the country, you realize that the next question that anyone asks will be: Show me the math.

Paul

Yes, it’s the trillion dollar question, and we can avoid it. I just grabbed the bull by its horns and said, yes, let’s talk about this trillion dollar question. How do we finance an economic bill of rights? It’s a reasonable question. We can separate it into two parts. We have to ask: Where did the dollars and cents come from, and then where did the real resources come from? Because it’s true that every dollar of spending needs to be offset in some way, but it’s also true that we have to be really concerned with how to ensure we have enough affordable housing, which simply does not exist today. To ensure that every single person is housed means we’re going to have to build many houses, and that’s where the real resources kick in. So, is the economic bill of rights going to be expensive? You bet. But this is where the federal budget comes in. Presently, we have a federal budget that subsidizes violence and imperialism, and we need to transition that to a federal budget that prioritizes care and human wellbeing. That is eminently reasonable. I actually look at a lot of the numbers in the book where, if we want a Medicare for All type program, will taxes go up on many middle income people? I’m honest, and yes, they will. But that’s not the right question we need to be asking ourselves. What we care about isn’t just if my taxes go up. At the end of the day, will I have more money in my pocket, or less? Will I have more stable health insurance, or less? If you’re under the Medicare for All program—which is cheaper than our current program, I should mention—we are going to have a system where you’re guaranteed health care your entire life, while the average American has substantially more money in their pocket at the end of the day. We should think about all the co-pays, deductibles, health insurance premiums—those are all essentially taxes. So, we’re just going to say all that’s going to get taken out of your paycheck instead. And in fact, we don’t even need to take as much out as you currently pay. People will be made better off, and that’s what really matters. As an economist, we call this discretionary income after you pay for your basics. Are you going to have more money to spend on leisure and have health care? The answer is yes, and that’s a pretty damn good trade off.

Robinson

Yes, we really have to do a lot of work to destroy this kind of framing in politics that is very annoying, and applies to the way that the deficit is talked about. You write about deficit spending in the final part of the book, and spending, generally. You saw this even in the Democratic primary debates in 2020, where a bunch of candidates would discuss how much Medicare for All would cost, or Republicans would look at the size of the deficit. You write that you can’t just point to a big number and act as if the money is being thrown in a hole and set on fire. The money is being used to get things that are supposed to make you better off. By pointing to one side of the balance sheet, which is the spending, and drawing people’s attention away from the massive benefits that you get from the spending, you’re not rationally assessing whether spending this money is a good way to get the desired result because you’re excluding discussion of the result. They’re just talking about the money.

Paul

Yes, but you’re thinking about things here rationally, Nathan, and that’s precisely what we’re trying to avoid. In all seriousness, a lot of these rights that I outlined in the book would involve substantial public outlays of funds, but they’d also involve a tremendous amount of savings. This is something that we don’t talk nearly enough about, which is how expensive our current messed up system is—how expensive the current higher education and health insurance systems are for everyday Americans. I have a good job, and I pay $830 a month for health insurance premiums. It’s a lot of money if my taxes go up $500 a year, but I don’t have to pay that $830 and health care premiums anymore, and I am better off at the end of the day. Also, I know I won’t have to switch health insurance.

Again, I calculated the numbers since I’ve been an adult: I’ve been on 14 different health insurance plans. It is a terrible system. Will everybody have to switch if we move them over to a Medicare for All program? Yes, but it’s going to be a one-time thing. Speaking of funding, I want to bring up one other piece that I’d like us to be discussing more in our political debates, which is this idea of a maximum income and maximum level of wealth. We talk a lot about minimum wages, but what we don’t talk enough about is maximum wages. Roosevelt actually first proposed a maximum income, which is the equivalent of about $425,000 today.

Not only did he propose this to raise money for important social programs—and here I fully agree with Roosevelt—he thought this was essential to protect our democracy and ensure we didn’t crumble into oligarchy, which is precisely where we find ourselves today. We’re a government ruled by and for the rich. How you prevent that is you use a fancy thing that economists like to talk about called the Pigouvian tax, which is a tax on social harms, like cigarettes and alcohol. You acknowledge the rich are a social harm, and it’s time we start taxing them accordingly.

Robinson

I’ve got a follow-up, though, by asking you—and it applies to a number of the proposals that you outline in the book—the classic libertarian response: But what about incentives? When you take away the possible reward for productivity, you’re not going to get your wonderful innovation and entrepreneurship. When you guarantee everyone a floor below which they cannot fall, they will become indolent and unproductive.

Paul

Do you know where most of our drugs end up coming from? They come from universities, where professors, not at all working in the for-profit model, often get funding from public agencies like the National Institutes of Health, and engage in research out of the love of research, in the desire for respect for themselves and from their colleagues, to come up with new and important life-saving innovations. So, do incentives matter? Yes, they really do. I agree. But is the financial incentive of becoming rich only one incentive in the huge array of incentives we could be considering? Absolutely. All I’m saying is, let’s move away from using the almighty dollar as the only incentive that we think humans respond to and move towards a system where we come up with a better system to reward humans for their ingenuity and creativity.

Prizes are just one good example, such as the coveted Nobel Prize. Everybody wants one, and folks work really hard their whole life for it. It comes with a fair bit of money these days, but that’s not why people are doing it. They’re doing it because they actually want to contribute to society. The other thing here is that when we look at these programs, and how they’ve been implemented either in the past in US history or in other contexts abroad, we actually find that the incentive issue doesn’t really pop up. So, let’s discuss the right to work here in the US.

When we had the Works Progress Administration during the Great Depression, which employed eight and a half million American workers, they had a whole fraud division because there were some in Congress that were worried about this. They essentially found no cases of fraud, or people on the public payroll that weren’t working. They didn’t find that getting rid of the threat of unemployment did away with workers’ willingness to work hard because people were in it together, put time and effort into creating a healthy workplace culture, and that incentivized folks to work. So, do incentives matter? Yes. But greed, contrary to what Gordon Gekko said, is not good.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.