How the Lottery Became a Substitute for Actual Hope

Instead of taxing the wealthiest, states fund important services through encouraging gambling habits. And instead of meaningful expectations for a better life, many people just have lotto tickets.

The American news media loves a story about the lottery. Whenever a popular numbers game like Powerball or Mega Millions rolls out an unusually high top prize, it triggers a cycle of breathless coverage, with frequent updates on the nation’s “lottery fever.” These stories are treated as headline news and broadcast alongside stories about war, elections, and natural disasters. Late in 2022, the Powerball jackpot reached a historic $2 billion, and the media circus escalated to new heights. From November 2 to November 8, when a winner finally emerged, NBC Nightly News ran a story every night about people flocking to buy lottery tickets, essentially providing a week of free advertising for the game. (In this time, they made no mention of the lethal war in Ethiopia’s Tigray region, which reached an important peace deal on November 2.) Local stations joined in the commotion, interviewing ticket purchasers and speculating endlessly about the chances someone from their area might win. Even on ordinary days, many TV channels embed within the actual news broadcasts daily segments devoted to revealing winning numbers. The lottery is a constant background radiation in the public consciousness. It’s in thousands of gas stations, convenience stores, and supermarkets across the country, with millions of players every year. But are lotteries really the fun, harmless pastimes they’re portrayed to be? Or is something more sinister going on?

In the first place, it’s important to recognize that lotteries are effectively impossible to win. For that $2 billion Powerball, the odds of picking correct numbers for all six “balls” were an eye-watering 1 in 292,201,338. For the Mega Millions game, which has a similar format with slightly more options per ball, the odds are even steeper at 1 in 302,575,350. Scratch-off games are harder to quantify, since there are so many different versions, but a typical ticket sold in Pennsylvania in 2021 had just ten $250,000 winners in a print run of “approximately 12,000,000,” making the likelihood of securing the grand prize something like 1 in 1,200,000. These are much worse odds than traditional casino games like roulette (where a straight bet on a single number has just 1 in 37 odds) or even slot machines (where the chance of getting all three jackpot images in a row is estimated at 1 in 262,144 on a typical three-reel machine.) Unfortunately, the human brain is notoriously bad at processing big numbers, so it can be hard to grasp what these figures actually mean. Told to picture “a million,” most people probably envision something closer to ten thousand; a hundred million, or a billion, is completely beyond ordinary experience. Here, colorful and slightly ridiculous examples can help. For instance, if an immortal vampire played a random set of Powerball numbers every day, it would take them more than 800,000 years to cash in. (292,201,338 / 365 = 800,551, to be exact.) For mere mortals, it’s technically possible, in the same way it’s possible that a crate full of money could fall off a truck and land at your feet—but for virtually everyone alive today, it won’t happen.

For this reason, lotteries have been called “a tax on people who don’t know math” (Bill Nye the Science Guy) and “a Tax upon unfortunate self-conceited fools” (17th-century economist Sir William Petty). These descriptions may be accurate on their face, but they’re also somewhat lacking in empathy. In most cases, “people who don’t know math” doesn’t actually mean “self-conceited fools,” only people who weren’t given an expensive education in probability and statistics. In other words, the poor and the underprivileged. In their PR materials, lottery industry groups get very defensive about the idea that they might be disproportionately affecting low-income people, calling it a “debunked myth.” Their customers, they insist, come from “society as a whole,” with 44 percent having incomes of $55,000 or more annually. But even if we assume this is true, it leaves another 56 percent unaccounted for—and more impartial research tells a different story. A 1989 study on lotteries by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that “the proportion of adults who participate drops from 49 percent for those with less than a high school education to 30 percent for those with a college degree,” and that “lotteries appeal to a less well-educated clientele [more] than most other forms of gambling,” which actually increase with a high school degree or higher. By itself, this suggests a class divide, since there’s a strong correlation between income and education—the richer you are, the more likely you are to graduate from a good college, and so on. A comprehensive literature review in the Journal of Gambling Studies supports this view, finding not only that “education remains negatively related to lottery gambling,” but that “an inverted U-shape relationship is found between SES [socioeconomic status] and lottery gambling,” with “a strong and positive relationship between sales and poverty rates.” (By contrast, the figure about incomes above $55,000 comes from Vision Critical, a “customer experience management” firm now rebranded as Alida which works directly with the lottery industry to market its products. You can probably draw your own conclusions.)

The heart of the issue is something deeper, though. Even if we take the lottery industry at its word, and assume that people from all economic groups play an equal amount, the impact would still be felt the hardest by poor and working-class people. According to the New York Times, “people with a household income of less than $10,000 a year who play the lottery spend $597 a year on tickets,” slightly higher than the national average of $540—but critically, this represents a much larger portion of their income than it would for any other group. $597 may be pocket change to some, but it’s a lot of money when you can’t afford to lose it, especially considering that in 2022, 49 percent of Americans reported that they didn’t have enough savings to cover an emergency expense of $400 or more. Something can technically be “equal” in one sense, and still be completely disproportionate in others.

There’s evidence that people with lower incomes play the lottery for fundamentally different reasons, too. In a 2004 study, three Cornell University economists tested competing rationales for why people who live “around the poverty line” might participate. According to the “entertainment hypothesis,” lotteries are just that: an inexpensive way of entertaining yourself, with each ticket offering admission to a “short, real-life drama” similar to a movie. The lotteries themselves embrace this “entertainment” narrative, with Michigan touting “fun and entertaining games of chance” in their mission statement, and Idaho coining an embarrassing neologism for it (“we embrace the phenomenon of ‘wooh’. The optimism, the fun, the joy.”). However, the Cornell study notes that there is another, darker possibility:

[C]onsumers, especially those in dire economic circumstances, see lotteries as a convenient and accessible tool for radically altering their standard of living, a government-run, financial “hail-mary strategy.” In short, bad times may cause desperation and the desperate may turn to lotteries in an effort to escape hardship. Such behavior predicted by the “desperation hypothesis” would have the unfortunate effect of further lowering wealth in households with already declining fortunes.

Of course, this isn’t necessarily an either/or proposition. Someone can simultaneously buy a lottery ticket for entertainment, and because they see it as a possible escape from poverty. But the “desperation hypothesis” is troubling, and the Cornell economists found evidence for it. If people are simply “economizing on their entertainment expenditures,” they reason, then we could “expect box office sales to also increase with poverty if consumers are simply seeking inexpensive entertainment,” at a comparable rate to lottery sales. Instead, they found “no evidence that poor consumers increase their consumption of movie tickets when their incomes decline,” while they do buy more lottery tickets. Drawing on previous surveys, the study also finds evidence that poverty and desperation influence people’s attitudes to lottery gambling:

When asked what is your “best chance to obtain half a million dollars or more in your lifetime,” 47% said “save and invest a portion of your income,” while 27% of all respondents said, “win a lottery or sweepstakes.” However, among respondents with incomes of $15,000 to $25,000, 45% chose a lottery while only 31% selected saving as the best opportunity to accumulate half a million dollars.

The pattern seems clear. In a time of worsening inequality, there are few real paths to upward social mobility, and for many people, winning the lottery might be the only way they can imagine achieving a better quality of life. The more precarious your economic status is, and the more limited your access to education, the more powerful the lottery’s appeal will be—and in a cruel irony, the greater the impact of the all-but-inevitable losses.

Like with many things in America, racism plays a role in all this. Lottery retailers are not distributed evenly throughout the country—instead, they cluster in certain areas, around certain people. In a 2010 study, Lyna Wiggins, a professor of urban planning, examined the geographic distribution of lottery machines and ticket counters in Middlesex County, New Jersey, and found that they were concentrated in minority neighborhoods. Specifically, “percent Hispanic was strongly significant in all the models predicting lottery outlet density and had the highest explanatory power other than percent commercial.” More recently, the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism found that lottery outlets are “disproportionately concentrated in communities with lower levels of education, lower levels of income and higher poverty rates, with larger populations of Black people and Hispanic people” on average throughout the U.S., and released an interactive map showing their exact locations.

Playing around with this “Lottery On Your Block” map is a fascinating experience. For instance, in Current Affairs’ native New Orleans, the median income in areas with lottery retailers is $43,636 compared to $55,292 in areas without, the Black population is 59 percent compared to 53, and the Hispanic population is 6 percent compared to 5. You can find more dramatic disparities elsewhere, like Georgia’s Fulton County ($67,802 average income with lotteries, $103,034 without them; 52 percent Black population in areas with, 32 percent without), but very few areas buck the trend. There’s a distinct echo of the way tobacco companies targeted minority audiences during the “menthol push” of the 1970s and ‘80s. Cigarettes and lottery tickets are often sold in the same places, using the same marketing tactics, and in the same era where brands like Kool were using the faces of legendary Black jazz musicians to peddle their wares, the Washington, D.C. lottery actually brought out a series of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.-themed ads exhorting the viewer to “honor his dream” (presumably by dreaming about big prizes). Not exactly subtle stuff.

At least the tobacco industry has been banned from most forms of advertising, though. Lotteries currently have no such limitations, and since they’re an arm of state government, they’re actually exempt from many of the regulations about deceptive and misleading practices that bind other advertisers. As a result, they promote themselves endlessly on TV, online, and in print, conducting elaborate media campaigns that would make Don Draper blush. They air commercials with Pixar-quality CG animation, team up with brands like Monopoly, Willy Wonka, the Dallas Cowboys and (perversely) Star Trek, and deploy all sorts of allegedly cute mascots and scenarios to make their pitch. In Pennsylvania, we’re bombarded with ads featuring Gus the Groundhog, a horrifying three-foot rodent who wears a shirt but no pants and tells people to “keep on scratching” their tickets; in Idaho and Georgia they have awkward lottery-themed rap videos (definitely nothing racial going on), and in California, people in fuzzy sweaters give each other tickets for Christmas while vaguely nostalgic music plays in the background. (If anyone is tempted to actually do this, they should remember Norm Macdonald’s classic standup routine on the subject: Here you go, nothing! Merry Christmas, it’s nothing, from me to you!)

In lottery ads, the emphasis is always on the possibility of winning, and the luxurious lifestyle you might lead, regardless of how unlikely it actually is. Images of limousines, cruise ships, and cartoonish piles of gold abound, and the word “dream” comes up a lot, with slogans like “What’s Your Dream?” (Minnesota) and “Dream Bigger!” (Kansas). The “desperation hypothesis” rears its head again, too; according to Robert Goodman’s 1995 book The Luck Business, the poorer neighborhoods of Chicago once had lottery billboards that literally read “This Could Be Your Ticket Out.” There’s a palpable cruelty, intended or not, to this messaging, akin to dangling a steak in front of a starving person only to yank it away at the last second.

The bright lights and colorful characters of lottery ads have another function, though: they appeal to children. In theory, it’s illegal to sell lottery tickets to anyone under 18, but since most states use vending machines, there’s no way to actually enforce the age restriction, and it’s commonplace for people to start playing in their early teens or younger. (Loiter around any gas station, and you can see this happen firsthand. Usually kids seem to start around the same time they discover energy drinks, which is a public health crisis for another day.) The Journal of Gambling Studies reports that lottery play is the most common form of underage gambling in both the U.S. and Canada, with as many as 15.3 million participants between the ages of 12 and 17, and it’s easy to see why.

Not only are the machines everywhere, but the lottery lacks the aura of sleaziness associated with things like slot machines or video poker; for many people, it may not be perceived as gambling at all. After all, if your favorite sports teams and cartoon characters are stamped on the tickets, how bad could it really be? The answer, of course, is very bad indeed, as research shows that underage gambling experiences can cause significant harm to “mental health functioning later in life,” with a strong correlation to “increased rates of a variety of risk behaviors, including alcohol use, substance use, seatbelt nonuse, driving after drinking alcohol, and violence,” and also put the young person at risk for addiction to gambling itself. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there’s also a racial gap in the rate of gambling addiction, which affects Black, Asian, and Native American communities at almost double the rate of white ones—a phenomenon with complex causes, but one in which the lottery and its marketing practices can’t be wholly innocent.

There’s a rationalization, of course. (Isn’t there always?) According to the lottery’s proponents, the whole sordid enterprise is ultimately worthwhile because the proceeds go to fund public goods: college scholarships in Arkansas, nature preserves in Colorado, programs for senior citizens in West Virginia, and so on. Obviously these are deserving causes, and they hearken back to the early days of U.S. history, when leaders like Benjamin Franklin organized lotteries to raise money for all sorts of infrastructure projects. The sums involved are sometimes impressive, like the estimated $900 million raised for Minnesota’s Environment & Natural Resources Trust Fund over the past 30 years, or the $22.6 billion (with a B!) that the Pennsylvania Lottery has contributed to senior care since 1972, at an average of roughly $443 million per year.

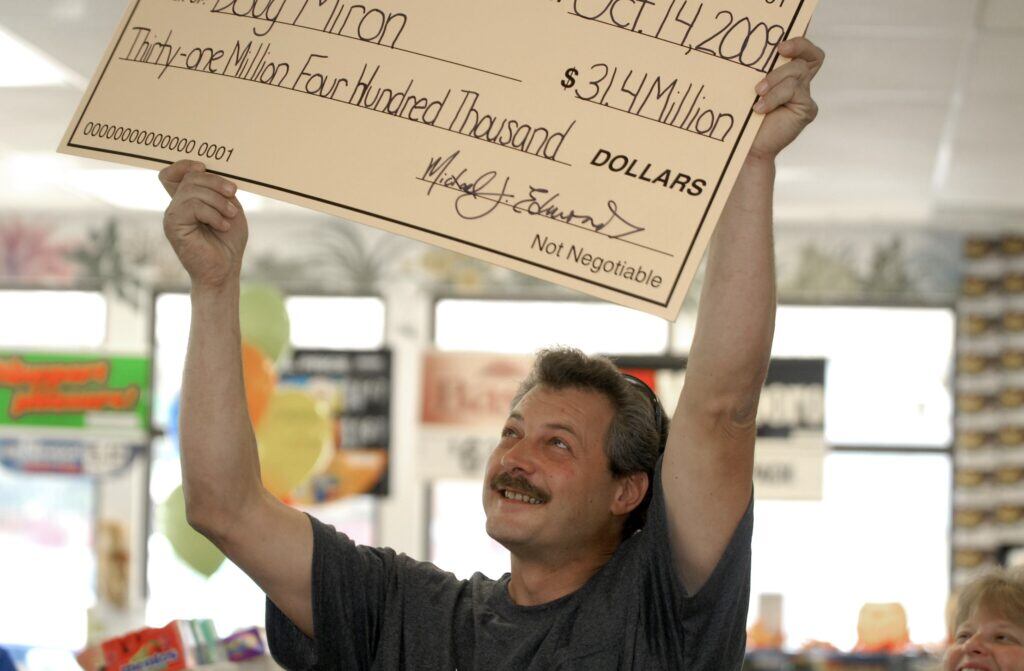

Unfortunately, though, there’s no guarantee that lottery revenue will actually have the impact it’s supposed to. In North Carolina, the state lottery was created in 2005 with the ostensible purpose of boosting education funding, but by the 2008-09 budget year, then-governor Bev Perdue had diverted $50 million in lottery money to the state’s general fund, followed by another $69 million in the 2009-10 budget. In Oklahoma, the $31.4 million the lottery contributed to K-12 education in 2014 was immediately canceled out, and then some, by a $216 million tax break for horizontal oil and gas drilling. And in Wisconsin, there isn’t even a fig leaf of public-spiritedness: the “cause” to be funded is simply property tax credits, meaning that only people rich enough to own property in the first place can benefit. Notably, former Wisconsin governor and enemy of the working class Scott Walker was a big fan of the state’s lottery, calling for a 40 percent increase in its advertising budget in 2017-19. From his perspective, the move made perfect sense. Lotteries siphon money from the poor, and use it to relieve the tax burden on the wealthy, either directly or by funding something that taxes otherwise would. In this sense, they’re a de facto tax in themselves, and a viciously regressive one.

Some remedies are obvious. For a start, there should be much tighter restrictions on lottery advertising, if not an outright ban. At the very least, the industry should be prevented from marketing its games with cartoons and animal mascots, as with other potentially-addictive products. (It’ll be no great loss: we’ve already put Joe Camel out to pasture, and at least he was undeniably cool.) In Massachusetts, some vending machines already require users to scan an ID proving they’re above 18 before buying lottery tickets, which seems like a sensible way of cutting down the underage-gambling issue across the board. More radically, you could eliminate machines entirely, and only allow sales by an actual human cashier. Retail locations could be subject to a licensing system, like with alcohol sales, and redistributed to correct disparities of race and class. More resources for gambling addiction, which causes 17 percent of its victims to attempt suicide, wouldn’t go amiss, along with prominent warnings on whatever lottery materials are still allowed. (Currently there’s just a lukewarm plea to “play responsibly,” usually written in tiny letters—can you spot it on this Illinois billboard?) Tax cuts and rebates associated with the lottery can be reexamined, and reversed when they’re only benefiting the upper income brackets.

The nice part is, most of these reforms can be carried out at the state level, and some could even be municipal ordinances. Mayors and city councils can experiment with different combinations of regulations, harm-reduction programs, and other measures, seeing what works and what doesn’t, before exporting the successes outward; it’s about time American federalism did something useful for once. The key point is that progressive-minded people who manage to get into office should at least have lotteries on their radar as an issue. Until now, the most effective campaigns against them have come from conservatives, and have been rooted in religious ideas about the immorality of “casting lots” rather than actual injustice. Their only real tactic has been outright bans, which is why heavily-evangelical Alabama and predominantly-Mormon Utah are two of the only remaining states without a lottery. (The others are Hawaii and Nevada, where the casino industry doesn’t want the competition; Alaska doesn’t participate in national games like Powerball, but started its own state lottery in 2017.)

From 1890 to 1934, lotteries were banned in every state except Louisiana and Delaware, thanks to a combination of evangelical pressure and highly public corruption scandals. The period overlapped with Prohibition, and like with alcohol, it turned out that simply banning things doesn’t address the deeper underlying problems that made people use and abuse them in the first place. (This is one of the rare points libertarians are right about.) Organized crime took the “numbers rackets” underground, where they became even more corrupt and extortionate than the legal versions (in some cities you could place bets on credit, running up catastrophic debts with your bookmaker). Ultimately nothing was solved, and when lotteries were re-legalized (starting, significantly, with Puerto Rico in 1934) they still bore strong traces of their racketeering history, and the exploitation that went with it.

What, then, would it mean to address the underlying issues? The answer is simple, and it’s one people are probably tired of hearing from socialists, but it’s still true. Rampant lottery gambling, like a hundred other horrors and absurdities, is just a morbid symptom. The disease is poverty, inequality, precarious living conditions, and lack of education—which is to say, capitalism, and a society centered around the almighty dollar. If everyone’s basic needs were already met, and everyone could reasonably expect to have some nice things in their lives from time to time, there would be little reason to play the lottery in hopes of striking it rich. If the world’s resources were more rationally distributed, and our public services were amply funded by something like Senator Bernie Sanders’ proposed Tax on Wall Street Speculation Act, the state would have much less reason to run lotteries. They wouldn’t even need to be banned, only reduced to a quaint hobby like chessboxing or philately. The lottery commodifies people’s misery and desire to escape the life they’re stuck in, and sells it back to them, and that may be its greatest crime. When we’re all free, its power will be at an end.