How Can We Trust What We See?

The deepfake era threatens to further erode people’s ability to tell truth from lies, and bring cynicism and conspiracism to new levels. We can keep this from happening, but it will take the hard work of building trustworthy media institutions.

Donald Trump’s conduct, as described in his latest criminal case, is pretty hard to defend. He has been caught on tape admitting that documents in his personal possession were classified. Even many who have previously stuck by Trump seem at a loss for words. “But Hillary Clinton didn’t get prosecuted over her mishandling of classified information” is the common refrain. Good luck trying that argument in front of a criminal court judge.

What’s left if all the evidence is against you? Well, you could just claim that the evidence is fake. This is what right-wing commentator Tim Pool did when he told his audience of more than 1.7 million Twitter followers: “That audio of trump? [sic] Probably just AI generate [sic] voice deepfakes.” Did he provide even a shred of evidence for this claim? Nope!

He didn’t need to. While some expressed skepticism, several commenters were quite willing to dismiss the audio on these grounds. “It’s easy to [make deepfakes]…I taught myself, so imagine what a government or media conglomerate could achieve,” one said. “Wouldn’t be the first time they doctored evidence,” said another. But just as concerning are people who said things like this:

“If we ever get anything that’s audio only nowadays, I’m not going to trust it by default regardless of what side of the aisle it’s supposed to make look bad. The fact that people put any stock in this audio at all reeks of desparation.” [sic]

While many of these people are simply looking for an easy excuse to dismiss evidence of Trump’s wrongdoing, they are getting at a problem that is very real. Distrust of media has been growing for a long time, but we can now also replicate people’s voices and images to an eerily realistic degree, and the possible uses of “deepfakes” are alarming indeed. It’s increasingly easy to fabricate convincing hoaxes. Millions of people were recently fooled by phony pictures of Pope Francis wearing a puffy Balenciaga jacket. An increasingly common meme involves fairly convincing AI generated audio of Presidents Trump, Obama, and Biden chatting like teenagers while playing video games together over Discord.

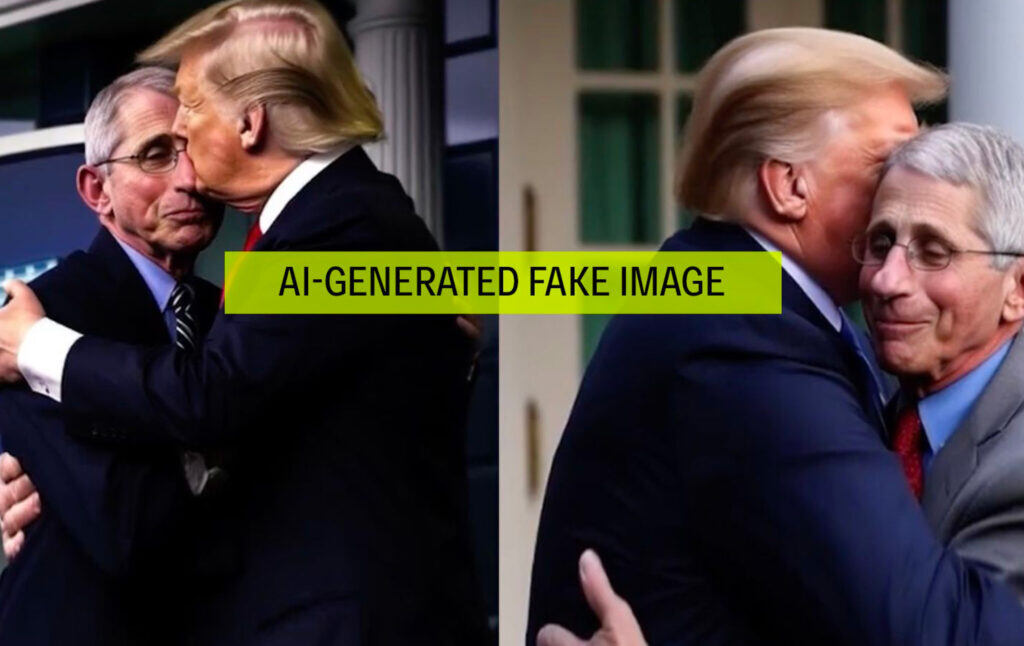

While the jokes are funny for now, the potential political uses of this technology are alarming, and already starting to come to fruition. The Ron DeSantis campaign recently used AI-generated pictures of Donald Trump embracing Anthony Fauci in its effort to discredit Trump with Republican voters (something Pool was, rightly, very upset about). The pictures weren’t particularly realistic, but someone casually scrolling through social media, not paying close attention and not particularly savvy about this stuff, might have been fooled, especially if the DeSantis people had put a tiny bit more effort into some photoshopping work.

Clearly, deepfakes can fool people into thinking that fake things are real. DeSantis will not be the last candidate to try to fabricate evidence of his opponent doing something that will turn off their voters. But Pool’s comment on the Trump tape makes clear another alarming consequence: the existence of deepfakes makes it much easier to assume that real things are fake. The possibility that anything could be an AI deepfake invites anyone to dismiss any piece of evidence that does not jibe with their worldview as fraudulent even if there is a perfectly real-looking photo, video, or sound clip of that thing happening. The reality of AI means that genuinely curious and honest people will not only be fooled by deepfakes, but be fooled by people like Pool into believing that genuine things are made up by people trying to manipulate them. Pool’s motives aside, he’s contributing to a propaganda strategy that may sever the final remaining strands of consensus reality that our political culture has left. Soon, it may be very difficult to know for sure whether any piece of information is authentic, and bad actors will take advantage of it.

This is a disaster. As deepfakes become totally indistinguishable from real video, audio, and pictures, it won’t necessarily be easy for even the most skeptical, careful person to know when they’re being fooled. How can we trust anything anymore? Are we doomed to slip into a world of total informational chaos where truth and falsehood barrage us with equal frequency, with no way of telling the two apart?

Not necessarily. But to fix the problem, we need institutions we can trust to vet information for us. Each individual consumer of information doesn’t have the time or capacity to carefully research whether something they’ve read or seen is true or a lie. So we need people with time and know-how to do it for us. But trust in institutions is slipping. Journalists should be the ones who vet information, yet Americans don’t seem to trust media institutions, as only 7 percent say they have “a great deal” of trust in media, according to Gallup.

That trust needs to be rebuilt. We need institutions that people can rely on to be straight with them. They need to be able to know that the outlet is not burying uncomfortable truths that conflict with its worldview. It’s not going to be easy to rebuild the shattered trust in media. But the first task is to acknowledge the scale of the problem, and the responsibility that we all have to create and support institutions that inspire the public’s confidence. It’s easy to lament the rise of “fake news,” to panic about the innumerable nefarious possibilities that deepfake technology opens up. But what we’ve got to do is start, from the ground up, building new organizations that demonstrate integrity and a commitment to truth and holding power accountable (what media should be doing anyway).

Our institutions as a whole aren’t trusted in part because they have discredited themselves. Take the justice system. People might be inclined to believe that evidence against Donald Trump could be fabricated, because they (rightly) don’t trust police, prosecutors, or the FBI. Or take healthcare. Lauren Fadiman has written for this magazine about how our for-profit healthcare system generates a rational mistrust of medicine that sometimes pushes people too far and into the realm of conspiracy theories. If people know that the pharmaceutical industry would kill them to make a profit (as Purdue Pharma did, when it deliberately misled doctors and patients about the addictiveness of Oxycontin), then it’s going to be harder to convince them to believe in genuine necessary medical interventions. If you know that an institution has economic incentives to lie to you and take advantage of you, your distrust of it makes sense.

AI programs themselves also need to be reined in to ensure that the photos, videos, and sounds they create are easily identifiable. AI generation tools like Midjourney, DALL-E, and the like should be required to have all of their images watermarked, as Microsoft and Adobe do with their image-creation softwares (China has already implemented laws mandating this, but the U.S. and E.U. lag behind). Failing that, these companies should be required to have experts on hand who can identify when a publicly-circulating image is the output from one of their products or a similar one.

The deepfake future is scary, not just because of the deepfakes’ potential to generate convincing hoaxes, but because in a world of hoaxes, people’s trust in each other could collapse. If you get a phone call purporting to be from your child, claiming they are in an emergency, how do you know it’s not a scam? Will using video and audio evidence in court even be possible? What’s to stop someone like Trump from just claiming that any incriminating evidence is merely an elaborate AI-generated hoax? The worst tendencies of our already fearful and suspicious society could spiral out of control. We shouldn’t have to live that way. But to have a media and judicial system that is actually trusted, we have to have a media and judicial system that are worth trusting. We have a responsibility to preserve truth and ensure that illusion and fakery are exposed and discredited.