How America’s Wars Become ‘Invisible’

Media critic Norman Solomon on how the U.S. media keeps the human consequences of the country’s foreign policy out of view.

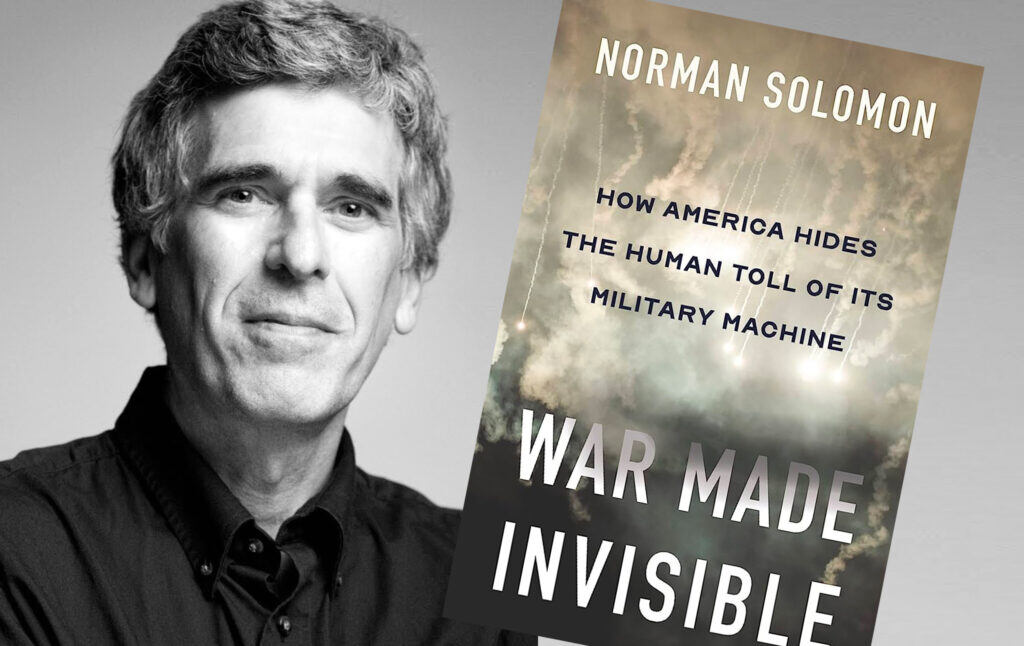

Today we speak to Norman Solomon about his new book War Made Invisible: How America Hides the Human Toll of Its Military Machine. Norman is one of the country’s leading progressive media critics. In the book, he talks about how the media helps construct a mental wall between the people of the United States and the victims of U.S. foreign policy. He talks about how the reality of violence is kept from view and how heroic whistleblowers like Chelsea Manning and Daniel Hale are punished when they try to put cracks in the “wall” and show people the reality of their country’s crimes abroad. The interview was conducted by Nathan J. Robinson and appeared originally on the Current Affairs podcast. It has been lightly edited for grammar and clarity.

Nathan J. Robinson

I want to begin by quoting a paragraph that stood out to me in your introduction:

“Patterns of convenient silence and deceptive messaging are as necessary for perpetual war as the Pentagon’s bombs and missiles, patterns so familiar that they’re apt to seem normal, even natural. But the uninformed consent of the governed is a perverse and hollow kind of consent. While short on genuine democracy, the process is long on fueling a constant state of war. To activate a more democratic process will require lifting of the fog that obscures the actual dynamics of militarism far away and close to home. To lift that fog, we need to recognize evasions and decode messages that are routine every day in the United States.”

I liked that paragraph because it captured a lot of the themes that run through War Made Invisible, one of which appears to be this connection between democracy and knowledge. That is to say, in a system where supposedly the voters are entrusted with holding power to account and have to decide who will be in charge, they can’t make those decisions well if things that are really important are, as your title puts it, made invisible.

Norman Solomon

Really, the uninformed consent of the governed is what makes the government’s world go round, you might say. If there were a really unfettered set of information streams, then arguably, the policy of the U.S. government, in terms of war and peace, for instance, would be really different. But the status quo is such that the challenges that are outlined in that paragraph you quoted are really with us 24/7.

In effect, we have not a complete control of media, but an overwhelming deluge of certain kinds of analysis, information, and assumptions about the world, and a real shortage of contrary views that might be more affirming of human life and the well-being of people in this country, and elsewhere in the world, rather than corporate profits and U.S. dominance of so much of the planet.

Robinson

You are writing in this book about those “patterns of convenient silence” and deceptive messaging, and trying to show us this huge gaping hole in ordinary people’s understanding of what their country does around the world.

Solomon

We might say it’s an engineered gaping hole. Sometimes when I’m told, “Well, I read this in the New York Times, which is very contrary to your claim that there’s a rigid propaganda system,” a metaphor that I think of and say is, “There’s a wall, and just because there are cracks in it doesn’t mean there isn’t a wall that is a retaining barrier that keeps the discourse really within bounds.”

There is, I would argue, a sick synergistic relationship between the fourth estate of the news media on the one hand and government on the other. They cross-reference and reinforce each other, and the bounds of discourse are shared. The information or misinformation is often shared, and what’s excluded—the silences—are also shared. One example is the U.S. has 750 military bases overseas and has spending every year on the military that is equivalent to the next 10 nations in the world. Those aren’t state secrets, they’re just rarely mentioned.

Robinson

Sticking with this idea of the wall, what you’ve given us are some facts that are on the other side of this wall that we don’t talk, think, or hear about very much. So, let’s talk about what else is on the other side of that wall, the things unseen and are made invisible. One basic thing that runs through the entire book is that there are people on the other side of that wall who are hurt and killed, and who go unseen by Americans.

Solomon

Yes, that the U.S. foreign policy, which is rarely called what it is—the continuing quest for empire (economic, military, and so forth)—has consequences, not only at home in what Martin Luther King, Jr. called “the demonic suction tube” that takes resources out of where it’s needed in this country for warfare overseas, but also people elsewhere on the planet who suffered directly and indirectly from the U.S. warfare state.

In working on the book, I felt it get more and more ugly. For all the self-preening in the United States about what a humane society we are, and all the rhetoric about how life is precious and how we love children and so forth, the discounting of the lives of human beings who are in the crossfire, or directly or indirectly hit by U.S. military firepower, are tacitly assumed to be of virtually no importance. The only importance that is ascribed to victims of war in any major way in the U..S media and the politics along Pennsylvania Avenue is whether the designated enemies of the U.S. government can be blamed for the killing.

The clear and recent example is in Ukraine. If only the U.S. media coverage of the U.S. slaughter in Iraq got the same appropriate journalistic treatment of the human beings in that country that we’ve been seeing for now well over a year, in terms of U.S. media coverage of the war in Ukraine, then we might have something that qualifies as journalism. In terms of foreign policy, we are in such an Orwellian realm that the definition of doublethink seems to really apply. On the shelf, information is tucked away until it’s useful, then it’s brought right down into the open, and then it’s brought back.

One quick example would be that we have heard for more than a year now statements by a Secretary of State Antony Blinken and President Biden and so forth that it is just absolutely wrong and unacceptable for one nation to invade another. Yet, both Blinken and Biden were very involved in the Senate—Biden chairing the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and Blinken as the Chief of Staff of that committee—in engineering and helping to push forward the U.S. invasion of Iraq with bogus hearings and then cheerleading for that war. So then, where are you?

Supposedly, we have a country with an intelligentsia and some single standard. Properly, we get denunciations of the Trumpist Republican Party. They are neo-fascists and make stuff up all the time and lie as a matter of course, that’s their knee-jerk M.O. Of course, they should be condemned. But what about the liberal Democratic Party establishment that is so enthusiastic about shipping weapons to Ukraine? These are members of, you might say, a liberal intelligentsia that are absolutely immersed in Orwellian doublethink when it comes to standards of international conduct.

Robinson

Yes, I think it’s worth dwelling on what the purpose and reason is to bring up United States conduct. Because oftentimes, when the argument that you’ve just made is made, the response that you will get to it is “what-about-ism.” Instead of just condemning Putin’s crime, you say, “What about these United States crimes?” But as I understand the point, it’s more like, are we not going to hold any of our own crimes to account? Are we really going to only righteously condemn the atrocities of other people and then commit far worse atrocities? The invasion of Iraq killed civilians on a scale vastly greater, so far, than the war in Ukraine even has. Yet, there are all these articles about how Democrats are somewhat nostalgic for George W. Bush now.

Solomon

Yes, very much, and I think it goes to some basic questions hidden in plain sight, which are: Are we going to have a single standard of human rights or not? Are we going to have a single standard of international conduct of nations? And when we get this complaint about “what-about-ism”, an irony is that can be spun 360 degrees. There’s always lots of “what-about-isms” allegedly or purportedly in any which direction. But the fact remains that either we’re going to have something that approximates, lacking a better term, intellectual integrity or not.

One of the things that is so stunning, disturbing, and appropriately enraging is that so much of the U.S. media establishment—arguably, almost all of it—and almost all on Capitol Hill have given up the ghost. They aren’t even trying to have a single standard of human rights. If it were otherwise, then the cries for Vladimir Putin to be tried as a war criminal would be augmented by the cries for, for instance, George W. Bush to be tried as a war criminal. But that is so far off the realm of what’s believed, asserted, or assumed to be reasonable discussion. We’re just way off the map as soon as we might raise anything like that.

Robinson

You cite in the book the example of widespread moral outrage at the Russian use of cluster bombs in Ukraine, without mentioning that the United States claims the right to use them. You cite the extraordinary number of cluster bombs used, 13,000, with over a million cluster bombs having what they call bomblets, with a total of millions of explosives dropped on Iraq within the first three weeks of the invasion. These are horrendous weapons that leave unexploded bombs for years that children find and are killed by. We claim the right to use them openly, and nobody’s ever held accountable, and yet we thunder against the outrageous Russian depravity in the using these horrendous weapons.

Solomon

We have this history that gets erased whenever we want it to be erased. And in this case, when the Russian invasion of Ukraine took place, the New York Times, among many outlets, just went into overdrive of condemnation over the use of cluster bombs, as their use should be subjected to. They’re just horrendous weapons, a certain kind of ultimate depravity and cruelty in warfare that is so terrible for civilians, really. Going back to the much ballyhooed and praised US-led 78 day NATO bombing of Serbia, cluster bombs were really part of that whole regimen. And then, as you mentioned, Iraq and Afghanistan were places that the U.S. used them. So, what does that all mean? Again, how do we exhume what is buried in a meaningful way? There’s independent journalism—we have outlets that are willing and able to do that—but we certainly don’t have the reach that the main media outlets do.

Robinson

You highlight in this book the fact that there are many ways the wall that stands between people in the United States and visions of the human consequences of US foreign policy is kept up. One of them is that people who leak information who have access to this information, who give it to the press and expose it to the public, are prosecuted and thrown in prison.

Solomon

If you are perpetrating the lies and denying the public the information that they have a right to, if we do actually believe in the informed consent of the governed rather than the uninformed consent of the governed and are helping to run and throttle the war machine, then it’s all considered to be alright, under secrecy and so forth. But this isn’t so for those who expose, and we have great examples: Daniel Ellsberg, Edward Snowden, and Chelsea Manning. These are heroic people who—no deed goes unpunished—the U.S. government has gone after with a vengeance, and to put it mildly, a double standard. We’re seeing that now in terms of Julian Assange as a publisher. He published stuff that the U.S. government didn’t want to see the light of day. We saw the so-called Collateral Murder video of the U.S., essentially through its employees, flippantly and cavalierly killing people from the air in Iraq, and through many other examples, from cables and so forth. Chelsea Manning goes to prison year after year for exposing that, and one would think this would be a crisis of conscience for people who take up the journalistic role as their profession.

And yet, there’s not a lot of evidence for that. It’s hard to bite the hand that signs your paycheck. When you come into the profession, the model for what professionalism is comes from what people are doing and not doing who are already more established in the profession. I think that’s what we’re looking at right now in terms of the US media. And in a sense, it always was.

Robinson

One of the most extraordinary cases that you cite in your book, that I think that most people still don’t know about, is the case of Daniel Hale. Daniel Hale is a descendant of the great American patriot, Nathan Hale, and has said that he feels like he’s trying to do the same thing in serving his country by releasing information to The Intercept about the civilian casualties of American drone strikes. It revealed that plenty of cases that were classified as being deaths of militants may not have been accurate, that the United States military didn’t actually really know that they had killed militants. He revealed evidence that may have amounted to war crimes prosecuted. He’s in prison right now. Ilhan Omar has asked President Biden to pardon him—he has not been pardoned, despite having received the Sam Adams Award for Integrity and Intelligence. The United States government, the Democratic administration, is keeping this man in prison right now for exposing information that the public needs to hear.

Solomon

Yes, and Daniel Hale now, in all likelihood, will spend several years in prison, sentenced above four years, and put in with some of the most allegedly terroristic people in U.S. custody. It’s not like he was put anywhere but in a very austere, punishing prison environment. It is ironic: his prior relatives, another whistleblower who I talked with and quote in the book, Sean Westmoreland, is a relative of the top US General in Vietnam, William Westmoreland. Sean told me that, as somebody who worked on the technology for relay of signals for drone strikes in Afghanistan, part of the model, increasingly, of the US.. war apparatus is that nobody’s responsible for everything or anything, and that there’s an understanding that you’re just a technological widget with no accountability whatsoever—you’re just turning the screws, so to speak, doing this little isolated silo job.

And so, there’s no sense of not only accountability in a job performance sense, but moral accountability. What Daniel Hale did is he said, “I do have some accountability. I know this, and I believe in democracy. I’m going to step forward and share the information.” I think one of the most moving pages of my book has the sentencing statement that Daniel Hill wrote with his own hand and gave to the judge. He said, “God help me, I could not have done anything else.”

And that, I think, is a really common theme that we hear from whistleblowers who have done these essential, creative, courageous things. It’s that they felt they could no longer be silent and had to take action, not only in a minor way, but to the best of their ability. That’s something that is a challenge to us. Daniel Ellsberg, who has unfortunately gotten a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and does not have long to live [note: this interview was conducted shortly before Ellsberg’s death], recently told an interviewer that when he met Greta Thunberg in Sweden, before she was famous and then later on, remembers her saying when people would bring up to her and articulate “you really inspire me,” after a while, her response became, “I’m inspiring you to do what?” Because in this commodity media culture that we have, we are encouraged to admire people to be “inspired by people”, including whistleblowers, but what does that mean? How does that change our actual behavior, our actions or lack of actions?

Robinson

Ellsberg has been particularly supportive. You actually quote a conversation that you had with him at the very end of your book, and he asks a question in that conversation that is going to stick with me about all the propaganda and things that we don’t know. Your book shows, as we said, how the wall is built and are kept from the truth, but he asks of the American people: How much would they do if they weren’t lied to? And I think that’s a really interesting question because we can say, “Well, we don’t know.” But then, once we do know, what’s our responsibility?

Ellsberg is someone who, the moment he did know and realized the truth about Vietnam that people weren’t aware of, realized that he had a moral obligation to risk life in prison. Daniel Hale is someone similar, who realized he had an obligation and couldn’t stay silent. So, I think that question of, once you know the facts, what do you have to do with those, is a really important one to keep thinking about.

Solomon

Individually, it’s very, so to speak, existential. And socially, it goes to maybe an almost ineffable matter of: What is culture? Antonio Gramsci discussed the well-understood notion of common sense, and what the proper behavior that people who are “normal” will engage in or won’t engage in. And we certainly don’t like to think of the US populace as people who are willing executioners, or watching and approving of, at least through passivity, willing executioners. After all, the best estimates say that the U.S. war on Vietnam killed 3 million Vietnamese people, and yet as I ran across working on this book, soon after Jimmy Carter became president, he was asked at a news conference, “Do you want the United States government to provide any assistance to the Vietnamese to recover from the war?” and President Carter’s response was emphatic: “We didn’t do anything wrong; we went there to help them, so we don’t owe them anything at all.”

This is an arguably somewhat liberal president. That’s a default position that the U.S. government, in many different contexts, takes, most recently with people in Afghanistan. My book outlines that the U.S. government basically stole several billion dollars from the Afghan people that belonged to the Afghan government that the US was supporting. And so, it’s better to, apparently by the reigning sensibilities in Washington, let Afghan people starve, than actually help them out in a way that might make it seem that the United States owes them anything at all. It’s more attractive to say, “We went there to help people and it didn’t work out—oops.”

Robinson

“I accidentally committed mass murder.” You mentioned what Jimmy Carter said about Vietnam, and you also quote him where he says one reason that we don’t owe them anything is because “the destruction was mutual.” And obviously, 50,000 US soldiers died in Vietnam, but U.S. civilians were not being targeted in Vietnam, and there’s simply no equality between 50,000 combat personnel and three million civilians. If you extended the Vietnam War Memorial to include all the Vietnamese victims, it would probably stretch into Virginia. And one of the things that comes up over and over again in your book is that Americans don’t necessarily understand, in part because of our methods of warfare put the victims out of sight with the heavy reliance on airpower. The massive disproportionality in the casualty count that American soldiers are, despite several thousand dying in Iraq and Afghanistan, actually very insulated much of the time from the violence.

Solomon

That’s more and more the case. The casualties suffering in engagement of U.S. troops has everything to do in correlation with the magnitude of media coverage—in the U.S. the main driver of coverage of any war is U.S. ground troops being involved. Air war is considered by the mass media and people on Capitol Hill and so forth to be a good thing. The perfect air war was the 78 day US-led NATO air war on Yugoslavia. There was a boast by President Clinton that not a single American died—how much more perfect can you get?

What’s really implicit and widely understood, if not articulated, per se, is that American lives really matter, and the lives of people that the Pentagon kills really don’t matter. It’s something very simple and straightforward in terms of media coverage, and certainly in the rhetoric out of Capitol Hill, to be believed, understood, embraced, propagated, and yet to even say that is not acceptable. It’s like the secret that isn’t a secret, but we’ve got to pretend it’s a secret. To shift metaphors, the story of the emperor’s new clothes: you can see it and is understood, but it would be considered a transgression politically, socially, perhaps even patriotically to openly pointed out.

Robinson

One of the quotes that opens your book is from Aldous Huxley: “The propagandist’s purpose is to make one set of people forget that certain other sets of people are human.” And in this book, over the course of it, you look at various areas around the world and how the American news media and the American government try to make us forget that the people in those places are, in fact, human.

Solomon

More than ever, I think that’s a powerful driver of the implicit messaging, the omissions and the commissions. About 15 years ago, I had a book come out called War Made Easy, and when I embarked on this new book, I was, of course, trying to think of a title. At first, I thought maybe it should be called, “More War Made Easy.” Then I realized that, especially because as you allude to, the U.S. more and more has fewer and fewer boots on the ground, is more and more reliant on air power, conventional bombing, and drones and so forth, and that it’s the invisibility of war that is increasingly characteristic of what’s going on.

I’m not saying that war was ever as visible through U.S. news media as it should have been—there are many filters. The myth of TV bringing war into our living rooms was always absurd. War is 180 degrees from sitting in your living room, under any circumstances, virtually. But in the last decade or so, as one president after another has, for political and military reasons, decided, “Why should we have all these troops on the ground when we can accomplish a lot of what we want to accomplish from the air?”, the ambience of coverage and non-coverage has really shifted. For the U.S. to be somewhere bombing somebody is a nonstory, and one of the myths that President Biden, with help from news media, has been propagating in the last two years is that the United States is no longer at war.

Soon after the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan almost two years ago, Biden went to the United Nations and said, “We’re turning the page, the United States is no longer at war.” This was a complete lie. And in fact, the U.S. was actively engaged at that very moment in warfare and military maneuvers in at least 80 countries. At Brown University, the Cost of War Project has really documented that extensively. So, I give the example that soon after that, Reuters did an article about the 2023 budget that the White House had put forward, and it referred to it as a “peacetime budget.” So, if Americans aren’t dying, it’s an air war, and the U.S. media coverage is derelict, to put it mildly—it’s not considered or deemed to be a war whatsoever. Of course, the people who are suffering and dying from U.S. firepower would beg to differ.

Robinson

You discuss the bombing of Libya under Obama and the way that the need for congressional authorization was skirted through these arguments that we weren’t at war because it was only our planes dropping bombs, and planes don’t count as part of war. It only counts if our soldiers are at risk or dying. But the infliction of violence from the sky is, by the United States and its NATO allies, just as you say, an invisible war, not a real one.

Solomon

It really borders on burlesque and self satire, an irony free zone, as in the category of “you can’t make this shit up.” In straight-faced testimony, representatives of the White House, in this case of Barack Obama, told a congressional committee that we’re not at war because Americans aren’t dying, even though we’re bombing and killing people in Libya, and spending in a matter of a few months a billion dollars to wage war there. But it’s okay because we say it’s okay. And besides, we’re not dying, or our people aren’t dying. This to me is just one of many examples. It makes explicit what is usually implicit and actually going on every day,

Robinson

You mentioned the Brown University Cost of War Project. I think page 160 is one of the most important pages of your book because that’s where you have this bulleted list of some of the things that they have found. They’re really an extraordinary research project and have really put together a lot of the facts that aren’t seen. If you go to their site as well, you can find out that they’ve tried to tally some of the human toll of the global War on Terror, not limiting it to the toll of the war in Afghanistan or Iraq, but seeing it as one united project. And when they put together all the casualties, you quote them reporting, “At least 929,000, nearly a million, people have died due to direct war violence. After two decades of the War on Terror, many times more have died indirectly due to ripple effects like malnutrition, damaged infrastructure, environmental degradation,” plus over 7,000 US soldiers to injuries, and deaths among contractors. Then there’s the staggering figure of 38 million people displaced by the post-9/11 wars in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Syria, Libya, Yemen, Somalia, and the Philippines—the largest human displacement since World War II. I think it can be shocking for Americans to even start to think about those numbers because they think, “But I’ve never heard about any of that.”

Solomon

Right. The displacement alone, where we have appropriately seen so much coverage of refugees streaming out of Ukraine in the last year plus, is something that can be recognized as a horror just as terrible for people to have to endure, and yet the routine infliction of those conditions on people is barely is a blip on the U.S. media screen.

Robinson

It’s extraordinary. Obviously, big numbers, generally, are very hard to fathom. And so, when you hear 38 million people have been displaced, the job of the news media should be to try and humanize those numbers and show us the experiences. You have some small examples: You actually went to Afghanistan at one point, and encountered some of the results of the U.S. war and met some people who have been affected by it, who, again, are totally off the radar of the United States media.

Solomon

Yes. And as you say, the numbers are very hard to fathom. The fact that, as the Cost of War Project has documented, the nearly one million people directly killed by the so-called War on Terror in the last 20 plus years is augmented by several times that many, through the cascading effects, are overwhelmingly civilians—that is one reality. And US media, when they want to, can really bring home the human cost—journalists are not great novelists, usually, but still, there can be tremendously powerful and moving news stories about the suffering of individuals or families. We have seen, heard, and read that about the Ukraine war, and yet the almost total absence of that when the killers weren’t Russians, but Americans, is a borderline taboo.

It’s not that it never happens, it’s just de-emphasized to the point of almost disappearance. And so, it raises the question, of course, of why. There’s nationalism and conformity. There’s a racial element: notoriously, right after the Russian invasion, a number of US reporters said these people who are suffering in Ukraine look like us, sometimes almost exactly in those words. It’s just stunning. And so, one of the points I make in the chapter called “The Color of War” is that at this point there is wide acknowledgement in US media, for the most part, that we have institutional and structural racism in this country and that it affects attitudes and policies of government and other institutions. And yet, we are encouraged to believe, through it not being ever brought up or virtually acknowledged, that racism has nothing to do with U.S. foreign policy or war making whatsoever.

As I mentioned in the book, it’s not that the U.S. government is killing people overseas because they are people of color, but the fact that they are makes it easier to keep killing them. And that is a reality that I can’t remember seeing in mass media, in this sense. I kept trying to think of people killed in the so-called War on Terror by the United States who are white. Maybe I’m just not realizing it, but as far as I can tell, very close to, if not 100%, of the people in the world who the US government has killed through the so-called War on Terror are all people of color. Talking about hidden in plain sight, where’s the outcry? Where’s even the discourse in US media about that?

And I think I should add, Nathan, that there are so many different components. We’ve been talking about media and so forth. If we go to Capitol Hill, there’s been a sea change with the Congressional Black Caucus. In the 1980s, African Americans in this country were the most anti-war demographic. One of the effects of the Obama administration was that the first Black president presided over normalizing bipartisan endless war through the course of corporatization and the power of military contractors, donations, lobbying, and media acceptance. The Congressional Black Caucus has gone from leadership of anti-war people like Ron Dellums, Shirley Chisholm, and John Conyers, to basically militaristic corporate flacks running it. And that has its political consequences as well.

Robinson

Yes. So thinking about the fact that, as I was reading this bulleted list of the projected costs of war, even the Costs of War Project, which has done a very good job of trying to quantify some of the toll, can’t begin to capture it. I always think back to an article we published a little while back, that quoted a 13-year-old from Pakistan whose grandmother had been killed by a U.S. drone strike. He told Congress, “I no longer love blue skies because the drone appeared out of a bright blue sky, and the drones couldn’t fly when the skies were gray.” His grandmother had loved blue skies, and on the days of the blue skies the drones came.

You quote in your book people talking about how terrifying it is to live with drones buzzing around—even people who aren’t killed in strikes live under this traumatic stress of the constant threat and menace of these wretched things. This little 13-year-old is not counted in the casualties—it was his grandmother who died. He didn’t get injured, but he is living with horrific trauma and stress, and this just doesn’t appear anywhere in the story.

Solomon

I think you’re making a profound point that when we start to look at these numbers, we look at a million people directly killed by this U.S. 20-plus year war effort, with several times that many indirectly effected from the cascading effects. What about the destruction of infrastructure, and of culture? What about the trauma? What about the ways in which countless millions of people, even if they aren’t physically displaced, are suffering from what we would call PTSD? So, we have this rampant destructive labyrinth of policy and implementation that is militarized and justified at home, but who is going to count the costs? Which is to say, who counts? If this happened to people in the United States, there would be a tremendous sense of martyrdom and victimization of the USA, which 9/11 helped to encourage.

As I say at the beginning of the book, 9/11 gave a sense of an embrace, a sense of absolution, that the United States therefore could never do anything wrong because 3,000 people had been killed. So now we have millions of people killed in the chain reaction, chosen by U.S. policymakers, but we’re still the victims. That is the framework of the tone of coverage, that we set out to do good. We make mistakes, we make miscalculations, but ultimately, we’re seeking to help people.

That 95% of the world is not in the United States is an abstraction. Because, as I write in the book, when it comes to grief, as a functional matter in U.S. media and mainstream politics, there are two tiers: there’s our grief, and their grief. If we are going to embrace surrogate “us” people, like in Ukraine because they’re being killed by an enemy of the US government, then we’ll somewhat let them into the first tier of grief. Whether you call that intellectual, psychological, spiritual, or whatever, when it is the mentality and policy of our own society to say that it is our tier of grief that really matters, and the other tier of grief is inconsequential, what kind of human beings are we?

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.