Why Effective Altruism and “Longtermism” Are Toxic Ideologies

Intellectual historian Émile P. Torres explains how Silicon Valley’s favorite ideas for changing the world for the better actually threaten to make it much, much worse.

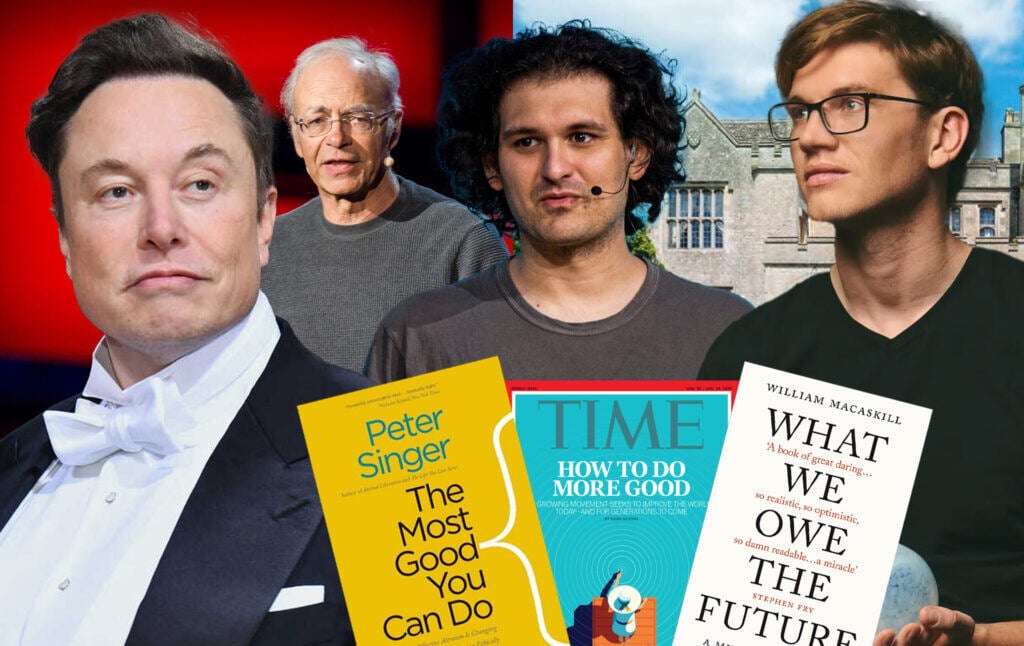

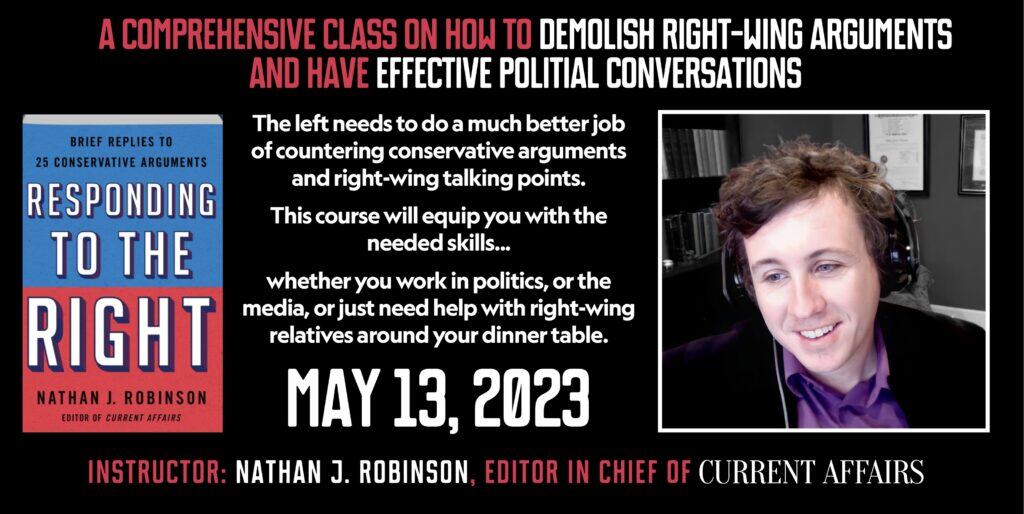

Émile P. Torres is an intellectual historian who has recently become a prominent public critic of the ideologies of “effective altruism” and “longtermism,” each of which is highly influential in Silicon Valley and which Émile argues contain worrying dystopian tendencies. In this conversation with Current Affairs editor in chief Nathan J. Robinson, Émile explains what these ideas are, why the people who subscribe to them think they can change the world in very positive ways, and why Émile has come to be so strongly critical of them. Émile discusses why philosophies that emphasize voluntary charity over redistributing political power have such appeal to plutocrats, and the danger of ideologies that promise “astronomical future value” to rationalize morally dubious near-term actions. The conversation originally appeared on the Current Affairs podcast and has been lightly edited for grammar and clarity.

Nathan J. Robinson

My worry about this conversation is that you and I agree, for the most part, about Effective Altruism and longtermism. We have both written about these things. And so we might end up speaking in ways that assume familiarity with them. Some of our readers may be totally unfamiliar with these ideas and don’t know why they should care. So, we need to begin at a place for those who don’t care.

I thought one question I could ask you to begin with was this: Let’s say that I am where I was in 2013, when I met my first Effective Altruist. They tried to tell me what this was all about and why I should believe it. Could you give me the pitch of what Effective Altruism is, and try to get me to become an Effective Altruist? In other words, let’s be fair to the ideology before we discuss why it’s so toxic and terrible.

Émile Torres

Yes. I think one way to approach understanding Effective Altruism is to decompose it into its two main components: the effective aspect, and then the altruism aspect.

[Let’s take the altruism first.] One thing that the Effective Altruists, or EAs, would point to is a paper written by utilitarian philosopher Peter Singer, published in the early 1970s. He basically made the argument that, if you’re walking home one day from work wearing new shoes and a really nice new suit, but then see maybe 20–30 feet away from you in a relatively shallow pond a small child who is drowning, most of us wouldn’t think twice about running into that lake to save the drowning child, thereby ruining our shoes and our suit. He basically made the case that most of us would reflexively run to save that child.

But what difference does it make that this helpless kid is 20–30 feet away from us? Because right now, all around the world, there are people suffering tremendously and dying. The statistics I saw most recently is something around 15,000 children die every single day of hunger related illnesses. And so, the argument was that rather than buy new shoes or a new suit in the first place, for those of us who reside in affluent nations in the Global North, what we should do is forbear buying those things in the first place, and take a portion—maybe even a significant amount—of our disposable income and donate it to charities that are going to help save the lives of children, so to speak, “drowning” in other parts of the world.

So, the proximity of suffering really shouldn’t matter. He’s gesturing at this idea of altruism, trying to make a case that we should be altruistic.

Robinson

And not just that we should be altruistic in a general sort of way. But from the premise that you would save a drowning child in front of you, take your nominal moral principles seriously and be consistent with them. And when we work them out and extrapolate them, we see that we have all of these other obligations that are no less pressing than our obligation would be to pull a child out of a lake if we saw them in front of us drowning.

Torres

Yes, exactly right. It’s inconsistent to sacrifice something to save the child, but then not to donate a significant portion of our disposable income to help people all around the world. So, this is the idea of altruism to help other human beings in the world.

But there’s a further question, which is the effective part. If one is convinced to be an altruist, there’s a second question, which is: which charities should I donate to? Should I give to disaster relief? Should I instead buy anti-malarial bed nets to protect people from malaria in certain regions of the world?

And so, this is where you get this idea of “Effective Altruism” being developed. In the 2000s, a number of philosophers at Oxford were trying to investigate this question, so they crunched the numbers and came to some conclusions that are oftentimes a bit counterintuitive—like actually, disaster relief is really not one of the best ways to get bang for your buck. You should donate anti-malarial bed nets or to deworming initiatives. The altruism part sort of goes back to the 1970s, but it wasn’t until the 2000s that people started to think somewhat quantitatively and try to crunch the numbers and answer in a robust way, based on science and reason, which charities one should give donations to maximize the positive impact they have in the world.

Robinson

You said a couple of times there “crunched the numbers,” which seems to be a major part of the actual Effective Altruism movement. It’s not just, “we have this expanded circle of moral obligations to our fellow creatures.” Because a kind of heavily quantitative utilitarianism is very much part of the Effective Altruists’ philosophy. Peter Singer is a famous utilitarian, and the essential utilitarian principle is you should maximize pleasure and minimize pain, or maximize the good and minimize the negative effect. Peter Singer’s book is called The Most Good You Can Do, and so it leads people who follow this philosophy to say we need to quantitatively compare how morally good various courses of action are.

And some of what they do in that respect seems to lead to conclusions that are pretty helpful. For example: is philanthropy donating to the Princeton Alumni Fund equally morally as good as trying to save people from malaria? That’s an obvious and extreme contrast, but they pointed out that plenty of charities don’t really measure the impact of what they do. When you start to look at the impact of charities, rather than how good it feels to donate to them or how glossy their brochure is, then you can actually make sure that the consequences of your actions in the world are as positive as they could be.

Torres

That’s exactly right. One doesn’t need to subscribe to the utilitarian ethical theory to be an Effective Altruist. But there’s no question that EA has been heavily influenced by utilitarianism. Utilitarianism offers a very quantitative approach to ethics, and somewhere around the core of EA, there is a bias towards the quantitative. I would agree that the question of what exactly is the impact of the efforts made by certain charities is a good thing to investigate and to try to better understand. There are criticisms that one could make about this particular approach. For example, some of the metrics that have been used in the past, “quality adjusted life years” and things of that nature, are somewhat problematic in different ways. But I think, at first glance, there is something appealing about the EA approach, and the spirit behind it is something that one might even applaud.

Robinson

Yes, it encourages us to be better people. And so, for people who do have the instinct that they would like their life to be meaningful and who derive meaning from helping other people, it says: how do you actually help others? We’re going to help you help others. I admire that, and it means that at first glance, Effective Altruism sounds almost unobjectionable. How could you object to altruism, and to making altruism more effective? These are so obvious.

But one of the places in which I think our critique starts is that the pitch tries to make it sound as if Effective Altruism is obvious, so much so that it would be hard to even mount any kind of argument against it. But when you look under the surface at the actual existing Effective Altruism movement, you quickly begin to find that it takes us to some bizarre places intellectually that are non-obvious to people, and, in fact, would make people quite uncomfortable in how they conflict with their basic moral instincts.

My first hint about this was when I was at a graduate student party and I saw someone making an argument from an Effective Altruist perspective, arguing with someone who was in law school. The law school student was going to work, I think, at the public defender or Legal Aid. And the Effective Altruist was telling her that was immoral, wrong, and she shouldn’t do that. Because correct the way to measure your actions and impact is by what would happen if you didn’t go to work at Legal Aid. And if you didn’t go to work with Legal Aid, someone else would; therefore, you’re not making any difference. What you think is good is actually not good at all.

In fact, what you should do, if you want to be good, is work at a Wall Street law firm, get a high salary, and donate that money to a malaria charity. And in fact, if you don’t do that and choose to go to work at Legal Aid, you are technically a worse person. I seem to recall that the person to whom this argument was being made got very upset, and the conversation didn’t end well. But that was where I started to think there was something very odd about this Effective Altruism thing.

Torres

Yes, that’s exactly right. So, this is the idea that we’re going to give, and part of the argument involves this counterfactual. If the aim is to save as many lives as possible, if you crunch the numbers, that might mean buying the highest number of bed nets. How do you buy the highest number of bed nets? One way is to get the most lucrative job you could possibly get, and that means working on Wall Street. For example, there are a bunch of EAs such as Matthew Wage, as well as somebody your audience might be familiar with, Sam Bankman-Fried, who went to work for a particular company called Jane Street Capital.

So, these are high-paying jobs. They have a greater income that they can take and spend on deworming initiatives or buying good antimalarial bed nets. The counterfactual comes in to the argument in the following way. Sure, some of these companies may be objectionable. MacAskill used this term in one of the papers he wrote defending this idea—

Robinson

I don’t think we’ve introduced MacAskill yet.

Torres

William MacAskill is one of the originators of the Effective Altruist philosophy, along with Toby Ord—both of them were at Oxford. MacAskill has become fairly well known as the poster boy of EA for the longest time, and more recently, has gotten a lot of press for his advocacy of “longtermism,” which we will also discuss momentarily, an offshoot of one of the main cause areas of Effective Altruism.

Will MacAskill used the term “evil organizations,” which may or may not be an appropriate descriptor for Jane Street Capital—he mentioned some petrochemical companies and so on. So, these are evil organizations. If we can agree on that, does that mean you shouldn’t go work for them? His argument was no. Because of the counterfactual argument that if you don’t work for these companies, somebody else is going to get the job, and chances are, those individuals are not going to siphon off a significant portion of their income for altruistic reasons to help other people around the world.

And consequently, all things considered, it would be better for you to just go ahead and take that job, work for a petrochemical company, Jane Street Capital, or maybe even go into crypto. Ultimately, the total amount of good that will result from that is perhaps much greater than if you went to work for a nonprofit and let somebody else take that job at the petrochemical company. That’s the counterfactual argument for earning to give.

Robinson

We have begun in the place where we say, “Don’t you care about other people?” and, “Don’t you want to be effective?” But then, very quickly, we have followed the logic to end up at, “Actually, people who work at petrochemical companies can be morally better than teachers and social workers because they donate more of their income to do more good in the world.”

Now, there are two parts of it: the earning to give, which is taking your salary at the evil organization and using it to do good, but not doing any good within the evil organization. Then there’s the question of, within the evil organization, could you mitigate the evil through your presence versus the presence of someone else?—what we might call the “Is it a moral obligation to be a concentration camp guard?” argument, which, in fact, MacAskill discussed.

As I was researching my article on Effective Altruism, he said, basically, You may be thinking when I make this argument, wouldn’t that mean that in Nazi Germany, the job of a good person would be to become a concentration camp guard so fewer sadists and sociopaths became concentration camp guards? Because if you refuse, and everyone who’s not a sadist or sociopath refuses, then only the sadists and sociopaths will be the concentration camp guards. I thought he wriggled out of this in a very unsatisfactory way, which was, he says something like, There are some things so immoral, nobody should do them, which being a concentration camp guard is, but working in a petrochemical company isn’t.

Torres

Yes, one of the criticisms of this particular argument that he propounded is precisely what you’re gesturing at, that he distinguishes the deeply objectionable careers or jobs versus the acceptably objectionable careers at evil organizations, like petrochemical companies. And the distinction between the two just isn’t really well-motivated. It does seem, at least to my eye, if you accept that, based on this counterfactual consideration, you should go work for a petrochemical company, that also seems to support the conclusion that you should be able to work at a concentration camp. Because again, like you said, maybe you’re an altruist, not a sociopath or a sadist. If you don’t take that job, a sociopath or sadist will.

So, there are all sorts of very strange, counterintuitive conclusions that many of the leading EAs have defended. They’ve also argued quite vigorously that we should actively support sweatshop labor in the Global South because it turns out that the jobs in sweatshops are better than the alternative jobs that people have. And so, by supporting the sweatshops, you are supporting the best jobs, relatively speaking, that exist in various places.

Robinson

Yes. And in fact, by protesting sweatshops, the opponents of sweatshop labor are worse people than the people who are building the sweatshops, who are actually the altruists.

Torres

So yes, pretty quickly, you end up with a number of views that I think many people find somewhat repugnant. But these are conclusions that follow from the EA premises. Much of this is really about working within systems. There’s almost no serious thought within EA, at least not that I’ve seen, about the origins of many problems around the world. Origins being in systems of power, structures that have enabled the individuals in the Global South to end up being very destitute—there’s no discussion of the legacies of colonialism. It’s about working within systems.

Robinson

It’s inconceivable to me to think of effective altruists talking about colonialism. The philosophy is just so far from touching that.

Torres

Yes. It’s pretty appalling the extent to which these other considerations about colonialism or capitalism, for example, are not really even on the radar of a lot of EAs.

Robinson

We mentioned the story of the person and the child drowning in the pond. When we start to think about where they start from and how the reasoning works, we notice upon closer examination that it is very much from the perspective of being an individual who has to decide how to do the most good as an individual, rather than as part of a collective movement where your individual contribution is not measurable. Participating in a political movement, you can’t measure your individual impact. So it’s hard to fit into the EA model at all.

There is very little discussion in the EA literature, although I’ve read people deny this—I don’t think those denials are credible—of the role of political movements in creating social change. A much more central question is: how much money could you donate? Which assumes that you are a person, probably in a Western country, who is able to earn a lot of money. There’s very little discussion of, for example, whether we should put a tax on rich people—after all, if you want to maximize the amount of good, it’s much easier to just have the state take the money from all the people who work on Wall Street, than for you, one person, to go to work on Wall Street and just donate your income while everyone else doesn’t.

Torres

That’s exactly right. It’s pretty astonishing the extent to which these other possibilities are ignored—or to use the term that they like, “neglected,” because they love to focus on topics that are neglected, as well as important and tractable. This is an issue that within the EA movement is extraordinarily neglected, and that’s a real shame. You made the point in your really excellent critique of EA and longtermism that socialism might be a good way to actually maximize the good that occurs in the world.

Robinson

Right. I am a socialist because I am a lowercase effective altruist. I think we can distinguish between “effective altruism” (lowercase), as in just caring about other people and trying to do it well, and this movement that has sprung up that focuses on particular ways to do good and uses particular styles of reasoning.

At this point, people might be wondering: is this movement significant? So far, we’ve laid out that there are these people who believe this thing, but I think you’ve made the case before that, as small as Effective Altruism might be, it has built up quite a lot of influence and funding. Could talk about why you think it’s worth everyone paying attention to these mistakes, rather than thinking it’s just some irrelevant movement that makes mistakes we don’t approve of?

Torres

The EA movement, at least before the catastrophic collapse of FTX last November, had $46.1 billion in committed funding, an enormous amount of money that they could spend on their research projects. Much of that money actually is funneled right back into the movement for movement building, as they would put it. Maybe there are some questionable purchases that they have made in an effort to further build their community. For example, they spent 15 million pounds on a palatial estate in Oxfordshire, just outside of Oxford. There’s a huge amount of money behind it. One of the main cause areas which we referenced earlier, longtermism, has become an ideology that is hugely influential in the tech industry. One could make the case that a fair amount of the research being conducted right now, in an attempt to create human level artificial intelligence or even artificial superintelligence, is motivated by longtermist ideology.

There are people in the tech sector who I’ve spoken to who have affirmed it’s absolutely ubiquitous in Silicon Valley. Elon Musk refers to longtermism as “a close match to my own philosophy.” And there are also reports over the past six months, at least, that indicate longtermist ideology is infiltrating major world governments— the US government, UK government, and the United Nations. There was a UN dispatch article in August that explicitly states foreign policy circles and the UN, in particular, are beginning to embrace the longtermist ideology.

Last summer, MacAskill published his comprehensive defense of longtermism called, What We Owe the Future, which coincided with a media blitz—New York Times, New Yorker, Guardian, BBC, Foreign Affairs, and so on—that covered MacAskill, EA, or longtermism, oftentimes quite favorably. And as a result, the public got their first glimpse of this ideology and what it is. But over the past few years, before longtermism, there was this big push to increase the public visibility of longtermism. Longtermists have been working somewhat behind the scenes to infiltrate the governments, to influence tech billionaires, to appeal to individuals in the tech sector.

So, I would make the case that it is an enormously powerful movement, and the ideology is very pervasive now. It’s really important that people understand what the ideology is and why it might be potentially dangerous, as I’ve argued on many occasions, and that they understand that this is not just some small group of people at the fringe. These are individuals who have tremendous power. And even after the collapse of FTX, which resulted in some of that $46.1 billion disappearing, just evaporating overnight, there still are just billions and billions of dollars that will be dedicated specifically to fund longtermist efforts, research projects, and so on. This is not something to ignore. This is very important.

Robinson

There’s a reason that you and I have spent so much time meticulously trying to expose the philosophical errors and dangerous implications of the ideas expounded by this movement, and it is because they threaten to have some success. In your last answer, you escalated the frequency of your use of the term “longtermism,” so I think now we have to now explain longtermism. Personally, if I had to do it succinctly, I’d start by going back to the story of the drowning child. If the first question that Peter Singer asks you is, “Why don’t you care equally about a child who is far away in space, on the other side of the world?” the longtermist follows up Mr. Singer’s question by asking you, “Why don’t you equally care about the child far away in time, born fifty, one thousand, a million years from now?” How would you introduce it?

Torres

Not even just a million.

Robinson

To get us started, a million.

Torres

I think that’s a really great way to introduce the idea. We shouldn’t spatially discount the suffering of somebody far away in space. It doesn’t count for less than the suffering of somebody who’s right next to us. In the same sense, we shouldn’t temporarlly discount the suffering of somebody a billion years from now. They don’t count for less than in deciding which actions we ought to take. We should include within our moral deliberations the predicament of people in the very far future, not just in the present. Basically, longtermism has roots that go back really to the 1980s, maybe even to the 19th century with a utilitarian philosopher named Henry Sidgwick, but it’s really the 1980s with Derek Parfit, and a few other philosophers right around that time who also addressed this particular issue.

But, I would say it was the last 20 years since 2002-2003 when Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom, another name that people might be familiar with, as he’s been in the news recently for a rather racist email…

Robinson

Rather extremely racist. We’ve discussed Bostrom on this program before in the context of his superintelligence theory in conversations with Benjamin Lee and Erik J. Larson, both touched on, so our listeners will be familiar with Bostrom.

Torres

Okay, awesome. In 2003, he published this article in which he took seriously the potential bigness of our future. So, here on Earth, homo sapiens have been around for 300,000 years, maybe 200,000 years. Our planet will remain habitable for another roughly billion years, possibly 800 million years, an enormously greater amount of time in our future just on this planet than in our past so far. In that sense, human history may be just beginning.

But of course, over the next 800 million or billion years, we might begin to colonize space, and if we do that, the future human population could become really enormous. There could be 10 to the 38 people (one of the numbers that he calculated) if we colonize our local supercluster of galaxies called the Virgo Supercluster. Compare 10 to the 38 to 8 billion people on Earth right now: one number is many orders of magnitude greater than the other. In subsequent calculations, he suggested that there could be maybe upwards of 10 to the 58 people within our future light cone, the region of space that is theoretically accessible to us.

This calculation particularly relied on the possibility not just that we go out and create space stations that could house tens of millions of people, so-called O’Neill cylinders would be one example, or that we inhabit Earth-like exoplanets orbiting their own stars, but also we could gather material resources in space, build giant planet-sized computers and then run high-resolution simulations in which you could have digital people interacting with each other living happy lives. The idea is that you can fit a lot more people within our future light cone, within the accessible universe. But if it’s just people, you can just fit them on exoplanets. If we build these computers, then we can maximize the future population even more.

So, the way that this fits with EA is, during the 2000s, they established this philosophy, the central aim is to do the most good possible. And then some of them encountered Bostrom’s work, read this paper and thought, “Wow, the future could be really enormous, and there could be astronomical numbers of people in the future. So, if I want to do the most good I possibly can, and since I want to positively influence the highest number of people possible, and there are far more people existing in the far future than there are at present, maybe what I should do is pivot away from the contemporary realm and focus instead on the very far future. Maybe there are actions I can take today that will have some kind of nontrivial impact on people in the future.”

So, if there are 1.3 billion people in multidimensional poverty today, you can imagine you’ve got finite resources, and lifting all of these individuals out of multidimensional poverty does something very good. But if you were to take an action that affected just 1%, or maybe a much smaller percentage than that, of the 10 to the 58 people who exist in the future, in absolute terms, that is a much higher number of people. Therefore, if you are really altruistic, you should not be focusing on currently existing people, and instead, be focusing on these far future people.

Robinson

You have told us a story that some people might think sounds a little ridiculous, thinking billions of years into the future. But I think the point that you ultimately end up at is critical, which is that if you follow from the utilitarian premise that we have to maximize the good, this can be where you end up! You can end up saying: well, what about the people billions of years in the future? And what you then end up doing, correspondingly, is saying that the most pressing needs of our moment, like poverty, climate change, and anything that does not outright threaten to cut the species off and make us completely extinct, really doesn’t matter very much.

Torres

Yes, I think that is a conclusion that follows pretty straightforwardly from this ideology. In practice, there are a number of longtermists who do donate to alleviate global poverty, and do care about some of these shorter term issues. The worry is that the ideology itself implies that contemporary problems, the suffering of current day people, matters only insofar as focusing on those things will improve the very far future. Because, again, the key idea is that the future could be huge—not just could be huge, but should be huge. Bigger is better, as MacAskill argues in his book, and that is very consistent with the utilitarian ethical theory that has, significantly, inspired this sort of perspective on our current situation and how we ought to act these days, and why we should be focusing primarily on people in the very far future.

So, there is a danger, that if people take longtermism seriously, by virtue of the bigness of the future, that will trump contemporary problems in every circumstance. I think climate change, for example, is probably not going to be an “existential” risk—as they would say, there’ll be some people left, and almost certainly not going to result in human extinction. One way it could is if there’s a runaway greenhouse effect, but the best science available right now suggests that’s very improbable. So, if you take this cosmic perspective on the human predicament, climate change shrinks to almost nothing. If we were to phase out fossil fuels in the 21st century, the effects would last for maybe 10,000 years. 10,000 years is a very long time. But that’s many generations of future humans who would be suffering the consequences of catastrophic climate change. But in the grand scheme of things—

Robinson

In the grand scheme of things, that doesn’t matter at all!

Torres

It’s not that much. And we could exist into the future, another 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 years—that absolutely dwarfs 10,000.

Robinson

It becomes an excuse for not caring about contemporary problems, and a moral justification for spending all your time just researching how to simulate human consciousness because once you can run simulations of human beings on the computer, you can just maximize the number of them that you make, your little fake people. And as long as you’re running them, you’re dwarfing any of the moral catastrophes that your actions are unleashing.

It also gives you cover to do destructive things in the name of creating this vast ultimate good. So not just not caring about contemporary problems, but making problems worse if they get us towards that glorious, long term utopian future. In fact, you’ve cited longtermist arguments that it’s actually more moral to care about people in the West than in the Global South because they’re the people who can go on and do all the good.

Torres

Yes, exactly. I think there are two related but distinct issues here. One is the possibility that the longtermist ideology will lead true believers to minimize, trivialize, or ignore the contemporary problems because one ought to be focusing instead on the very far future, millions, billions, trillions of years from now. The other issue is the possibility that it might actually “justify” in the minds of true believers extreme, potentially violent, actions today for realizing this kind of techno-utopian world among the stars, full of astronomical amounts of value.

And I think this is a serious objection to make. After all, history is full of movements that became violent, started wars, engaged in terrorism, and were motivated by this vision of astronomical or infinite amounts of value in the future. They don’t justify the means, but the ends are so valuable, nothing is off the table. Nick Bostrom himself has argued that preemptive violence might be necessary to protect our future. You just mentioned an idea that comes from a dissertation published in 2013 by Nick Beckstead, who’s also one of the founders of the longtermist ideology. And he, I think, draws the correct conclusion from the premises of longtermism which is that if what matters most is how things go in the very far future, then you should prioritize saving the lives of people in rich countries over the lives of people in poor countries. And the reason is that rich countries have more economic productivity, innovation, and so on. And these are the things that will influence the very far future, not trying to help individuals who are struggling to eat three times a day to actually get those meals. So, this is an idea from the literature that underlines the potential danger. It underlines just how radical the longtermist view can be if it’s taken seriously.

Robinson

A couple of other things that threaten to follow from the premises are: a contempt for democracy—because obviously if you’ve discovered the mathematical, objectively correct way to determine the human ends that should be pursued, it doesn’t really matter what anyone else has to say about it. They’re objectively wrong. There’s a certain arrogance and assumption that the people who have found the answers are entitled to impose them upon anyone else. And correspondingly, there is this belief that elites ought to rule, those who have discovered these morally optimal mathematical truths. You’ve even pointed out that eugenicist language flows through this movement—if you want to “optimize” human beings and to better the species, there can be some ugly possibilities that flow out of the internal logic held by those who adhere to this movement.

Torres

Yes, that’s right. One component of the longtermist ideology is a particular ethic called transhumanism. Nick Bostrom is one of the most prominent defenders and champions of this transhumanist philosophy—the idea that the emerging technologies, things like genetic engineering, synthetic biology, molecular nanotechnology, AI, and so on, may enable us to radically modify the human organism in various ways and will result in modes of existence that are better in some very significant ways than our current mode, like maybe we’re able to become superintelligence and think thoughts that are completely out of our epistemic reach, ideas that we just cannot even entertain. Perhaps we can begin to solve some of the mysteries of the universe that right now are just unattainable for us. We could also become immortal.

Transhumanism says not only will we be able to radically enhance humanity in the future, but we should pursue these technologies—some have called them “person engineering technologies”—and through a kind of intelligent redesign, modify ourselves to become a new, superior post-human species. This connects quite directly with 20th century eugenics. In fact, contemporarily, philosophers would classify transhumanism as a type of liberal eugenics, and would argue that the qualifier “liberal” makes all the difference in the world, morally speaking.

I actually would object to that, and I think they’re good arguments for why transhumanism in practice would ultimately be quite illiberal. But even beyond its classification as a kind of eugenics today, this idea of transhumanism was developed by the more authoritarian illiberal genesis of the 20th century. J. B. S. Haldane is one example, J. D. Bernal is another, and in particular, Julian Huxley. Huxley was president of the British Eugenics Society from 1959 to 1962, and was really one of the most vocal and vigorous advocates of eugenics throughout the 20th century. In the second half of the 20th century, in particular, he popularized this idea of transhumanism. So, there’s a direct genealogical link as well.

And maybe another thing to mention, just in terms of the connection here, not only does transhumanism and longtermism have roots that go directly back to 20th century authoritarian eugenics, but many of those eugenicists from the past century were animated and motivated by certain racist, xenophobic, ableist, and classist attitudes. If you wander around the neighborhood of longtermism, and transhumanism as well, it is difficult not to see those same attitudes all over the place. So, that’s worrisome as well. There are plenty of advocates of transhumanism and longtermism who, if you ask them, will explicitly denounce these sorts of attitudes, but if you read some of the things they’ve they’ve written, or listen to some of the things that they’ve said, it becomes apparent that actually some of these discriminatory kind of views are really quite ubiquitous.

Robinson

Yes. Nick Bostrom was just in trouble for this old, incredibly racist email announcing a belief in Black inferiority and using the N-word and such. But I’ve heard effective altruists say, “What relevance is it one of the prominent figures said or held a racist attitude?” Well, to me, the relevance is that you’re part of a movement that believes that elites based out of a castle in Oxford should rule the world! That’s what the relevance is. And of course, they don’t believe that African people are capable of deciding what’s best for Africa—they believe that they have mathematically decided what’s best for Africa.

But here’s where I want to finish up. I think it is easy for a normal person who is not a longtermist to listen to our conversation and think, “That sounds crazy and scary, I don’t want those people to have any power.” But if I was a longtermist or an Effective Altruist, I would listen and think, “You have shown that if you follow our premises, you get to certain places that you think are bad places to end up, without showing why they’re bad.” I’ve seen people say this about you: “Émile Torres says that longtermism leads to the conclusion that it’s morally necessary to create billions of simulated humans on a computer. Yes, and what’s wrong with that? That’s correct. If it follows from the premises, and the premises are the right ones, then it’s true.”

So I want to finish up by asking you: where do they go wrong? Which of the premises do we reject? You say that, actually, they are following their philosophy consistently, so we have to go to the root. We have to ask, at what point is it that you should stop following Peter Singer down to his “Do you care about the child? Okay, do you care about this child? Then you have to care about the billions of potential children that we can make in the future.” In fact, I think MacAskill himself said that effective altruists take you on a train to crazy town, and everyone’s got to get off somewhere—for him, it’s before becoming an EA concentration camp guard, but not before becoming a petrochemical engineer. How do you stop the train from getting out of the station to begin with, philosophically speaking?

Torres

Yes, there are a couple of things to say. Trying to predict the future, in general, is really hard. It’s a good laugh to go and read about predictions that were made in the 1950s about what 2023 would look like. How can we have even a remotely accurate idea of what the future might be like in a thousand or million, billion, trillion years from now? We’re just absolutely clueless about what the future is going to look like. I think that’s one problem. Once you recognize that we are clueless, that supports focusing more on issues that we aren’t clueless about, such as global poverty, climate change, environmental destruction, and so on.

Another issue is the longtermist view of human extinction. You referenced this earlier. As we were saying, it’s very intertwined with a utilitarian kind of ethical framework. And on the utilitarian view, one way to understand it is that there is no intrinsic difference between the non-birth of somebody who would have a happy life, and the sudden death of somebody who has a happy life because all that matters is the total quantity of value in the universe as a whole. From this perspective, not only are we morally obliged to try to increase the well-being of individuals who currently exist, but we’re also obliged to increase the human population, insofar as new people would have net positive amounts of well-being. The more of those people we create, the better the universe will become in general.

Robinson

But let’s pause, and ask: does that mean that if I don’t have kids, every child I don’t have is basically a child I’m murdering, or “nothing out” of existence?

Torres

It’s a bit complicated because maybe if you murder someone that might involve inflicting suffering on them—perhaps if you were to painlessly remove someone. So, what you have to do when I say, “There’s no intrinsic difference” is I’m somewhat bracketing out all the other possible consequences, and it may be horrible to remove someone from existence because that would impact their friends and family and so on. Whereas, the non-birth of somebody wouldn’t necessarily impact currently existing people in the very same way. But ultimately, on the utilitarian view, we are just these containers of value. We matter only instrumentally, only as a means to an end. What is the end? The end is maximizing value or well-being.

Ultimately, if we have these containers that exist in the world called people, we want to fill them with as much wellbeing as possible. But we also, to maximize value, want to create new containers that have positive amounts of well-being. The more containers we create, the better the universe will become. This leads to the view that it would be terrible, for example, if we were to become extinct. Let’s say we go extinct in a thermonuclear conflict, that would be pretty bad for two reasons: one is 8 billion people would die horrible deaths; the second reason, which is actually a much more significant reason ethically speaking, according to utilitarianism, is that all of these future possible people will never be born. And the non-birth of these possible people in the far future means that the universe as a whole will contain far less value than it otherwise could have contained, and that would be an absolute moral catastrophe, in their view.

So, part of the longtermist arguments about why we should prioritize avoiding human extinction over things like alleviating global poverty—some of them have literally made this argument—rests on a certain philosophical view that among philosophers is highly contentious, and in my view, very implausible, that the non-birth of all these future people, including all these future digital people, would be some kind of really awful catastrophe. And again, by virtue of the numbers of these future people, you have a good longtermist argument for why you should not focus on contemporary issues so much. Instead, you should be focusing on them, including ensuring that they exist in the first place.

Robinson

Yes, the idea of maximizing an abstract quantity like “value” seems insane to me. And maximizing is never a good idea. I don’t think you should ever maximize—you should always get the right amount of things. Because maximization is what we might call cancer logic—a cancer maximizes itself. A cancer is a perfect example of, “let me produce as much of myself as possible.” Uncontrolled economic growth—that’s maximization logic. Don’t maximize; get the right amount!

I also think it’s more helpful to think in terms of intergenerational justice, which incidentally existed as a concept long before longtermism, and is much more reasonable. It just thinks about future generations and how we have a responsibility to them. To me, the “long-term” question seems easily resolved in part by saying, “We’ll deal with that future when we get to it.” What I mean by that is that right now, we have all these incredibly pressing problems, which will be a terrible inheritance for the next few generations. If we can make life for those next few generations much better, if we can solve all these short-term problems, then a few generations from now, we can start to have some “longtermists” who can then say, “We’ve solved all the short-term problems so now let’s look at some of the really long-term ones.”

Torres

Yes, I totally agree.

Listen to the full conversation here. Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.