The Timeless Relevance of Hugo and Zola

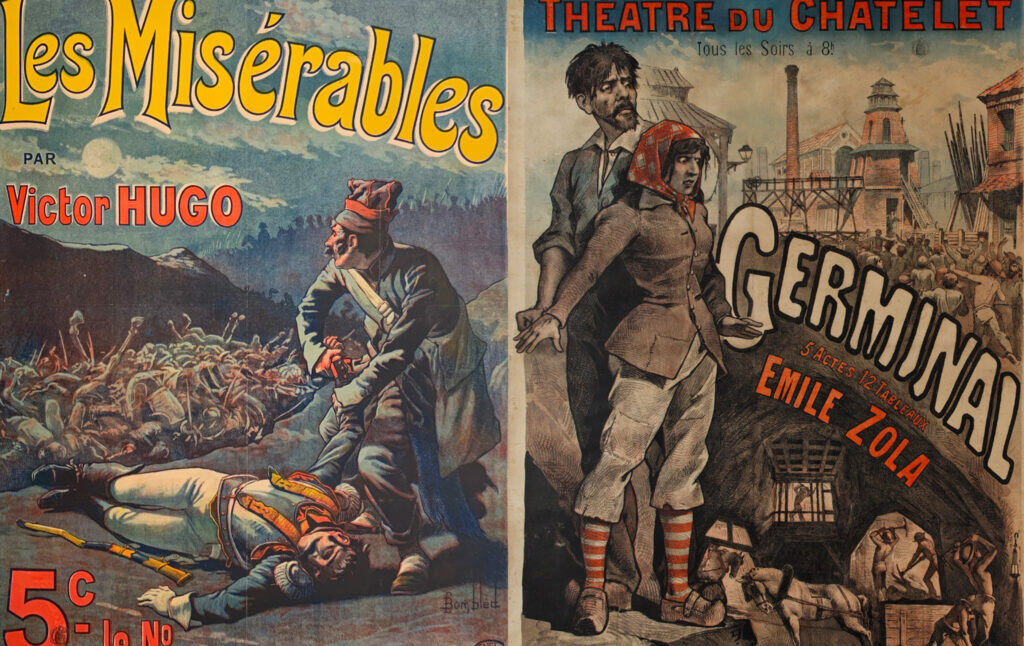

When Victor Hugo wrote Les Misérables, he hoped that “books of this kind may serve some purpose.” And they do. The 19th century social novels of Hugo and Émile Zola remain insightful on issues of labor and economic injustice in our own time.

“Are there any factories in Montsou?” the young man asked.

The old man coughed up some phlegm and then spoke up loudly against the wind:

“Oh, there are plenty of factories, all right. You should’ve seen ‘em three or four years ago, thundering away, they couldn’t find enough workmen, never was so much money about … but now we’ve got to tighten our belts again. It’s a crying shame round here, people laid off, workshops closing down, one after the other. … Maybe it’s not the Emperor’s own fault; but why does he need to go off to fight in America? Not to mention the cattle that’s dying of cholera, like everyone else.”

Émile Zola, Germinal

The opening section to one of the most enduring novels in the French literary tradition is not a particularly cheery one. When Étienne Lantier arrives in the fictional town of Montsou in search of a job, he does not expect to come face to face with a microcosm of the capitalist system that rules the French countryside. Zola channeled his considerable intellect and literary talent into a tale of how brutal poverty pushes a ragged group of miners to struggle against both the intransigent greed of their bosses and the ruthless ferocity of their greatest ally, the state. Passages like this one give us a portrait of rural 19th-century France steeped in the particulars of Zola’s era, yet it remains uncomfortably pertinent—the same way James Baldwin’s thoughts on contemporaneous American race relations remind us of all the work still to be done to end systemic racism and all its harmful downstream effects.

The 19th century was a big one for socialism: Kropotkin, Das Kapital, the revolutions of 1848. It was also a century that gave us some of our most enduring writers, the century where English poet Percy Shelley famously wrote, “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” Long before the advent of literary styles like the frequently obscure and esoteric Modernism or the “nothing makes sense so let’s just riff on it all” jokiness of Postmodernism, 19th-century European literature concerned itself first and foremost with humans’ relationship to the world we inhabit and the societies we construct and uphold. Some novelists, such as Jane Austen and Mark Twain, used wit and humor to poke fun at strictures of class, gender hierarchies, and racism. Others like Charles Dickens or Leo Tolstoy sought both to expose and offer compelling alternative moral visions to the repressive conditions of, say, English workhouses or Russian serfdom. Simply (and very reductively) put, the 19th century was a period in which writers—or, at the very least, the authors whose works have stood the test of time—took themselves seriously enough to believe that their work had relevance beyond itself and the academy.

As an appreciator of everything from Dostoevsky to Lorrie Moore, I must assure you that my goal is not to turn to the literature of the past to make a broader critical point at the expense of the present. Instead, I want to look at it for its own sake, to dive into two novels that remain acclaimed within academic and intellectual circles but which time, cultural remove, and other gatekeepers may have obscured from even the readers of Current Affairs or other erudite Americans: Zola’s Germinal and Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. What might these books offer modern readers more than a century later? More than you might suspect: gripping narratives and unforgettable characters; deep concern for the plight of workers and the oppressed the world over; and the exemplary wisdom of their authors, many of whose observations seem to apply just as neatly to our—or any—society as they do to 19th-century France. In these times of extreme inequality and unceasing capitalistic extraction, the left needs novels such as these for sustenance as much as we need movements, leaders like Bernie Sanders, or other publications like Jacobin. In the age of Twitter and “hot takes,” we could all stand to read books that require sustained attention. If we do, we might find more than just a little bit of “hidden” wisdom in the writings of a couple of Frenchmen, now long dead but whose words can still teach us about the ongoing struggle for a free and just world.

“Books of this kind may serve some purpose”

Born in 1802 to an officer in Napoleon’s army, Victor Hugo is widely considered one of the greatest authors ever to write in French. The author of dozens of novels and plays and hundreds of poems, Hugo was a preeminent man of letters within contemporaneous French society. He was also a politician, elected to both the National Assembly and the Senate, and an activist, one of his primary causes célèbres having been a fierce opposition to the death penalty. By the time of Hugo’s death in 1885, his popularity among the French citizenry was such that his funeral in Paris attracted more than 2 million people, more than the city’s population at the time and a large enough audience that the French government usurped management of the funeral out of fear of a potential uprising. Hugo’s massive influence on French political and literary culture still lingers, so much so that it is estimated that every town in the entire country of France has at least one street named after the writer-politician.

Despite his work’s influence on socialist organizers and movements throughout history (Eugene Victor Debs, named for the writer, reportedly read Les Misérables over and over throughout his life), Hugo was far from a committed socialist in his own political career. Coming onto the literary scene amidst a restored post-Napoleonic French monarchy, Hugo failed his first political test during the revolutions of 1848 by taking the side of the royalists, fighting against the barricades that he would immortalize in his most famous novel. Only in the revolution’s aftermath did he become “radicalized,” veering towards the left as he became one of the leading Republican reformist opposition voices to the absolutist government of Louis Napoleon. Once he left Paris in exile after Louis Napoleon’s successful anti-constitutionalist coup in 1851, Hugo garnered a reputation as a political radical, both by lending his vocal support to movements around the world and writing the book that has most cemented his historical reputation, Les Misérables. When he returned from exile upon the declaration of France’s Third Republic in 1870, he was immediately elected as a senator. He failed another crucial political test upon refusing a suggestion to run for a place on the central committee of the now legendary Paris Commune, whose goals he apparently supported but whose methods he condemned alongside the violence of the state in a textbook example of “both sides”-ism usually the domain of tepid liberals.1 After the Commune’s brutal dismantling, Hugo must have seen the error of his ways, for he opened his home to persecuted communards and fought for their complete political amnesty, drawing the ire of numerous contemporaries but rallying the support of working people across France.

Hugo was at the forefront of the artistic movement known as Romanticism, itself a kind of backlash or response to the Enlightenment thinkers who had dominated European intellectual currents throughout the 18th century. Where the Enlightenment stressed rationality and order, the Romantics preferred to emphasize emotion and embrace the mysterious aspects of human life. Furthermore, artists no longer adhered quite as strictly to classically accepted approaches to artistic composition, instead placing more emphasis on the sublimity of nature and its connection with the imaginations of the individual artists. Perhaps it was Alfred de Musset, noted French poet and dramaturge, who offered up the most characteristic elucidation of the Romantic movement:

Romanticism is the star which weeps, the wind which cries out, the night which shivers, the flower which gives its scent, the bird which flies. … It is the infinite and the starry, the warmth, the broken, the sober, and yet at the same time the plain and the round, the diamond-shaped, the pyramidal, the vivid, the restrained, the embraced, the turbulent.

Published in 1862 after nearly twenty years of work, Les Misérables first appeared on the literary scene after the Romantic movement had largely given way to writers like Balzac and Flaubert, who themselves spearheaded a response movement appropriately known as Realism. Despite its later publication, Hugo’s great novel still exhibits many of the paradigmatic trends of the movement of which its author had spent the previous decades at the forefront, notably its grandeur and sweep. In this regard, no idea for Hugo is too grand or unparseable to avoid scrutiny. Within the more than 1,300 pages that make up Les Misérables, Hugo touches on God, revolution, poverty, faith, goodness, evil, authority, freedom, nationalism, unity, capital punishment, social justice, and class struggle (just to name a few). Anyone who has seen the novel’s famous musical adaptation can attest to the gripping nature of the plot, but the narrative is merely one aspect of a novel whose primary subject is nothing less than all the grandeur and drama inherent to human life.

In line with both his literary proclivities and the better angels of his political nature, Hugo wrote with the idea that his novel could bear witness to the kinds of conditions that can surround and catalyze social upheaval. Such testimony might then help effect change, laying the moral groundwork for the kind of society dreamers like Hugo envisioned. The best evidence of this comes at the novel’s very beginning in this brief epigraph:

As long as through the workings of laws and customs there exists a damnation-by-society artificially creating hell in the very midst of civilization and complicating destiny, which is divine, with a man-made fate; as long as the three problems of the age are not resolved: the debasement of men through proletarianization, the moral degradation of women through hunger, and the blighting of children by keeping them in darkness; as long as in certain strata social suffocation is possible; in other words and from an even broader perspective, as long as there are ignorance and poverty on earth, books of this kind may serve some purpose.

Passages like this—many similar ones can be found among Hugo’s other writings and extensive correspondence—are a rarer sight in contemporary literature, which I sometimes fear has all but resigned itself to a fate of cultural obsolescence (surveys have documented declining rates of literature reading among American adults). For Hugo, however, art might not merely observe or poke fun at the world but might actually probe its depths enough to inspire change. A common attitude among his contemporaries, such an attitude is, today, practically radical.

Rather than wade into the historical forests of the 1789 or 1848 revolutions, Hugo chose for the setting of his novel the June Rebellion of 1832, an obscure (and swiftly curtailed) anti-monarchist revolt of Parisian republicans. The novel may technically take place in the midst of a real event, but Hugo’s interest lies less in historical verisimilitude than in using the insurrection as a kind of blank literary canvas on which he can expound upon his broader attitudes towards revolution and progress. In fact, the setting is probably better understood as a stand-in for (and perhaps an atonement for his mistaken allegiances in) the revolutions of 1848, which the great sociologist Karl Marx considered the first meaningfully working-class revolutions in European history. The novel’s more vague temporal setting does much to explain the story’s lasting appeal and ongoing inspiration to revolutionaries the world over.

Even if you’ve never read the original novel, you may have a sense of its plot and characters, either through cultural osmosis or exposure to any one of the novel’s adaptations, the most popular of which remains the 1985 West End musical and its numerous revivals (plus an adaptation into a pretty bad movie in 2012 that does not do justice to Claude-Michel Schönberg’s musical score, let alone Hugo’s tome). The story functionally begins with the introduction of Jean Valjean upon his release from a 19-year prison sentence, originally conferred as punishment for his theft of a single loaf of bread to feed his starving family. After a benevolent rural bishop helps the former convict get back on his feet, the novel follows Jean Valjean through the rest of his life, which he strives to fill with acts of honesty and charity to atone for his criminal past. He takes into his care Cosette, the daughter of a young factory worker turned sex worker named Fantine, and eventually becomes entangled in an uprising of a student movement known as the ABCs,2 one of whose members, young Marius, has fallen in love with Cosette. Like he has a hellhound on his trail, Jean Valjean spends decades evading pursuit by the infamous Javert, a police inspector whose ferocity is outmatched only by his reverence for authority. The chase culminates after the destruction of the novel’s famous barricade, leading Javert and Valjean, with the body of an unconscious Marius in tow, to a final climactic encounter in the Parisian sewers in a section long considered one of the richest in all of French literature.

Hugo’s characters are some of the most memorable in any work of fiction I’ve ever encountered. Jean Valjean and Fantine have become literary archetypes for the victims of a system that condemns innocent people to poverty and suffering. A clear autobiographical stand-in for the author in the similarity of their political trajectories, Marius Pontmercy disowns the inheritance of his royalist grandfather when he grows into a more egalitarian political consciousness, eventually putting his life on the line at the barricades for his ideals. The Thénardiers, a quasi-foster family from whose mistreatment Valjean rescues his adoptive daughter Cosette, exemplify the greed and wickedness of the petite bourgeoisie who care more about losing a precarious middle-class existence than envisioning a world of kindness and justice. Just as distinctive as Hugo’s principal characters, however, are the numerous minor characters that fill the novel’s pages, from the heroic street orphan Gavroche to Marius’ dastardly royalist uncle Monsieur Gillenormand, for whom Hugo elicits sympathy for his grief over Marius’ decision to abandon the family. My personal favorite of these side characters is Monsieur Mabeuf, an initially apolitical man whose circumstances drive him to financial ruin, which forces him to sell his prized collection of rare books to make ends meet in his old age. Radicalized by his destitution, Mabeuf ultimately comes around to the cause of the ABCs, eventually sacrificing his life on the barricades in the name of their revolutionary cause.

For Hugo, no person, historical or fictitious, is uninteresting. Though he includes extensive digressions on the lives of “great men” like Napoleon or King Louis-Philippe, Hugo is even more interested in the lives of the normal people mired in poverty and oppression for whom he names his novel. Far from making them mere caricatures or one-dimensional symbols, Hugo breathes life into his characters, who come off as profoundly real people as notable for their struggles within and against oppression as for their societal trappings. Though inextricably tied to their social circumstances, characters like Marius or Jean Valjean continue to speak to readers precisely because they are dynamic people who seek to build a life within the confines of a society that simultaneously stifles them and (more importantly) begs to be overthrown.

Les Misérables has long been recognized as shorthand for the overlong novel, reportedly one of the longest ever written at more than 650,000 words. Aside from its gripping plot and memorable characters, Hugo’s massive novel is in this vein particularly (in)famous for its extended digressions, estimated to comprise nearly a quarter of its more than 1,300 pages. Some of these digressions relate to the novel’s broader themes of revolution and social consciousness. Many of them, however, are almost completely unrelated to the book’s general thrust, such as when Hugo decides to expound upon his historical theories surrounding Napoleon’s infamous defeat at Waterloo in 1815 or to take several dozen pages relating his general contempt for the cloistered lifestyle of monastic Christian orders and their isolation from pressing material concerns. Though some of these digressions can get a bit cumbersome—I never thought I would learn so much about the layout of the Parisian sewage system circa 1832, a topic for which my interest is practically nonexistent—they serve a function of profound importance in terms of lending extreme verisimilitude to the novel’s milieu.

Any reader could be reasonably excused from skimming through or even entirely jumping past, say, Hugo’s extensive cataloging of contemporaneous Parisian slang, especially given the gripping plot from which Hugo is asking his readers to deviate. To write off such passages, however, would be to ignore Hugo’s larger interest in examining and critiquing the society that has shaped his characters’ material circumstances. As much due as he gives his story’s individual actors, Hugo is, throughout the novel, perhaps even more interested in dissecting the structures that both defined the France of his time and that still resonate for those living under today’s oppressive global capitalist order.

Take, for example, this passage from the novel’s early pages, where Hugo uses the Bishop of Digne as a mouthpiece for one of the most concise condemnations of the social “order” you’ll ever read:

The failings of women, children and servants, of the feeble, the destitute and the ignorant, are the fault of their husbands, fathers and masters, of the strong, the rich, and the learned. … Teach those who are ignorant as much as you can. Society is to blame for not giving free education. It’s responsible for the darkness it produces. In any benighted soul—that’s where sin is committed. It’s not he who commits the sin that’s to blame but he who causes the darkness to prevail.

Or this one, where in the midst of Jean Valjean’s unraveling backstory, Hugo rhetorically interrogates in the loftiest of Romantic terms the reasons a person might be driven to commit a crime:

Does human nature change so thoroughly and so radically? Can the human being created good by God be made wicked by man? Can the soul be completely remade by fate and, being ill-fated, become ill-natured? Can the heart grow deformed and develop incurable uglinesses and infirmities under the pressure of inordinate misfortune, like the spine under too low a vault? Is there not in every human soul, was there not in the soul of Jean Valjean in particular an original spark, a divine element, incorruptible in this world, immortal in the next, which goodness is capable of nurturing, stoking, kindling, fanning into a glorious blaze of brilliance, and which evil can very wholly extinguish?

(Hugo’s implicit response to each of these questions is a resounding yes.)

Or how about this one, which sadly resonates in light of my own government’s continued commitment to its military apparatus instead of robust social spending?:

It has been calculated that in salvoes, royal and military honors, exchanges of courtesy volley, ceremonial signals, harbor and citadel formalities, sunrise and sunset salutes et cetera, the civilized world was discharging around the globe every twenty-four hours one hundred and fifty thousand unnecessary cannon shots. At six francs per cannon shot, that comes to nine hundred thousand francs a day, three hundred million a year, that go up in smoke. This is just one small detail. Meanwhile the poor are dying of hunger.

Even more than in the thrilling description of battles at the barricade erected between Rue Plumet Idyll and Rue St-Denis Epic, passages like these are where the core of Hugo’s social critique best shines through. A perennial adherent to the movement he helped define, the author can occasionally issue statements that came off as a little overwrought or grand, particularly to modern readers like us who might be a little less conditioned to think of the world in Christian absolutes like good and evil, virtue and sin. These Romantic pronouncements are more than lofty language, but act as a conduit for Hugo’s otherwise very material understanding and critique of 19th-century France and human civilization more generally.

Such trappings of his artistic proclivities superficially obscure Hugo’s very clear and incisive framing of the novel’s most definitive conflict: that between the authority of an unjust order and the resistance that strives to replace it with a just one. Nowhere is this more evident than in the character of Inspector Javert, one of literature’s most memorable villains. From the outset, Hugo establishes the officer of the law as a simplistic man dominated by “two very simple sentiments … respect for authority and hatred of rebellion,” the latter of which Javert defines to include “theft, murder, [and] any crime.” He views “any state official, from the prime minister to the rural policeman, with a deep-seated blind faith,” whereas on “anyone who had once crossed the legal threshold of wrong-doing he heaped scorn, loathing and disgust.”

It would have been easy and not wholly ungenerous for Hugo to paint Javert one-dimensionally, as an unquestioning arm of the law deserving of only reproach, not sympathy. Instead, Javert is more than a mere foil for his heroes but another conduit into larger societal critique. His backstory, given very early in the novel, characterizes Javert if not equally a victim as Valjean or Fantine, then at least as equally subjected to his fate by the strictures of society. Consider this passage, which Hugo gives us very early in the novel:

Javert was born in prison of a fortune teller whose husband was a convicted felon. As he grew up, he believed he was on the outside of society and had no hope of ever being let in. He observed that society unforgivingly kept out two classes of men, those who attack it and those who guard it. He had the choice between these two classes only. At the same time he was conscious of some underlying inflexibility, steadiness and probity within him, compounded by an inexpressible hatred for that gypsy race to which he belonged. He joined the police.

It is not unbridled evil that compels Javert’s unwavering, decades-long pursuit of Jean Valjean; it is a respect for authority which, when it leads the believer to unquestioningly conflate authority with goodness and justice, turns the inspector into an agent of evil. It is only when Valjean spares his pursuer’s life at the novel’s end that Javert is forced into a crisis of consciousness. He is unable to reconcile his perceived moral duty to continue hunting a man who has just saved his life. “The law was no more than a broken stick in his hand,” Hugo writes. “Taking place inside him was an emotional epiphany completely distinct from any legal considerations, his sole yardstick until then.”

Deserted by that “blind faith that breeds a grim integrity,” Javert takes his own life, unable to bear the conflict between his duty and Valjean’s kindness. Javert may be a victim of himself and his own impulses, his own lack of moral imagination, but he is also a victim of the same system as Jean Valjean, the society that forced a starving man to steal and transformed a child born into misery into a trained practitioner of state violence. Killing off Javert in such a way shows us the depth of Hugo’s understanding of the ferocity of an oppressive order. Just as Fantine is driven to prostitution and eventual death by her poverty, Javert becomes a casualty of the same structures when he confronts the misplacement of their brutality first hand.

Despite numerous dark moments like these, Hugo’s novel is overall quite optimistic, perhaps even naive in its appraisal of the inevitability of societal progress. Such is the dominance of Hugo’s Romanticism, which doesn’t quite deign to visions of hopelessness. Though the novel certainly valorizes revolution, Hugo places even greater value on notions of progress and goodness, the presence and power of the latter ensuing the inevitable victory of the former. No matter the darkness of its depths, Hugo’s novel ultimately always returns to the optimism of the light.

Stranger Comes to (Company) Town

From a modern perspective, it’s easy to lump both Hugo and Zola into the same category of “dead white French guys,” but their respective biographies are quite distinct. Where Hugo was a child of a military officer and a member of the bourgeoisie his entire life, Zola was born in 1840 to poverty. Where Hugo was a Senator and a member of the académie française, Zola never passed his baccalaureate exams (the French educational system’s rough equivalent to an American high school degree, or British A-levels). Where Hugo waffled throughout his life around a tepid reformist conservatism despite his books’ radical propensities, Zola was far more directly antagonistic towards the French state, briefly convicted criminally over his advocacy on behalf of Alfred Dreyfus, a young French officer accused of treason on bogus—not to mention anti-Semitic—grounds during the famous Dreyfus Affair. The lingering (and somewhat stereotypical) perception of the outsized influence of national intellectuals on French politics and culture can perhaps most directly be traced back to Zola, whose original “J’accuse…!” invective against the government in the left-leaning newspaper L’Aurore caused a societal stir bigger than any Twitter controversy this side of Cat Person.

Zola’s influence and reputation tower comparably highly to Hugo’s within the literary world, if not necessarily the American cultural imagination (at least not until Hugh Jackman takes a turn as Étienne Lantier). A devotee of the earlier French Realists like Balzac and Flaubert, Zola spearheaded an offshoot of Realism known as Naturalism, which sought to frame and construct narratives under the guidance of scientific principles and with an encyclopedic attention to detail. In this regard, Charles Darwin was perhaps as much an influence on Zola as any literary precursor, not out of any positivist subscription to dog-eat-dog social Darwinist principles but because he understood and was curious about the way both hereditary and environmental factors influence human life.

That may sound indistinguishable from the roots of Hugo’s critique, and we are indeed able to trace numerous similarities between his systemic critique in Les Misérables and Zola’s in Germinal, his tale of miners striking against the capitalist system of greed that keeps them suffering. Reading the two novels side by side reveals a stark contrast, however, between Hugo’s lofty pronouncements about human progress and Zola’s gritty, even visceral interrogations of the dark and dangerous conditions under which late 19th-century coal miners toiled. Though Zola, like Hugo, was never a committed socialist in any sort of organized sense, he, like his Romantic forerunner, writes with a deep attention to and compassion for brutalized and repressed workers, as he was heavily informed by several months he spent in rural France alongside real-life miners.

Named for a month in the Revolutionary Calendar as determined by the Committee of Public Safety in the years after the Revolution of 1789, Germinal begins with the arrival of young migrant worker Étienne Lantier to Montsou, who has left the Paris of his abusive alcoholic family and wretched material poverty in search of work as a miner. It is not long before Lantier, upon witnessing the severity of the miners’ own poverty and the extent of their bosses’ greed, takes it upon himself to organize his new comrades into a strike that lasts through a cold and hungry winter. Though their commitment begins strong and hopes are high, the group’s collective enthusiasm wanes as an even greater poverty begins to take its toll on the miners and their hungry families—not to mention the vicious strikebreaking efforts of the police and the army that ultimately cause the deaths of several workers and their children (laws regulating and/or banning child labor were non-existent at the time). The strike continues as the novel barrels toward an unforgettable conclusion in the depths of a fragile mineshaft from which no one emerges unscathed. Like a good Realist-Naturalist, Zola refuses an easy, happy ending, instead leaving the reader with an imprint of the suffering he has spent more than 500 pages depicting.

Though relatively intriguing in their own right, Zola’s characters seem cardboard in comparison to the creations of Victor Hugo, who leap off the page and linger in the mind long after the novel’s close. Zola’s characters, however, serve a distinct purpose as archetypes through which the author explores the complex labor-capital ecosystem and the miners’ subsequent efforts to tip the scales. His characters run the gamut from the wild revolutionism of Souvarine, a Bakunin-style anarchist, to the bourgeois Hennebeau, who would rather incite the police to kill children than part with even a franc more than necessary in order to maintain profits. Some of the novel’s most interesting characters actually exist at least a degree from the labor-capital relationship. Zola shows us the petite bourgeois timidity of Rasseneur, a miner turned bar owner, after his early attempts to organize the miners, alongside the ruthlessness of a police captain who refuses to cease his fire lest he get in trouble with his superiors. Within this extensive polyphony, Zola rarely emerges as any kind of voice of conscience, a far cry from Hugo’s extensive and often moralizing digressions. A true Realist, he only wishes to portray the situation he has created as naturally and objectively as if it were real and he were reporting it for a newspaper. Even without directly inserting authorial commentary, Zola’s focus on material circumstances leads the reader to the most obvious conclusion of the workers’ rectitude and the owners’ evil.3

Many of the novel’s most intense passages deal with the viscera of such inhuman conditions, which Zola portrays with equal parts care and devastation. Take this passage, where the author personifies the danger of the mine:

He squatted down inside one of the tubs with his workmates, it plunged down again, then barely four minutes later, it surged back up again, ready to swallow down another load of men. For half an hour the pit gulped down these meals, in more or less greedy mouthfuls, depending on the depth of the level they were bound for, but without ever stopping, always hungry, its giant bowels capable of digesting a nation. It filled, and filled again, and the dark depths remained silent as the cage rose up from the void, silently opening its gaping jaws.

Or this one, a frank digression about the difficult nature of coal mining:

To tell the truth, it certainly wasn’t an easy trip. The distance from the coal-face to the incline was fifty or sixty meters; and the passage, which the stonemen had not yet widened, was hardly more than a gully, whose very uneven roof bulged and buckled all over the place: in some places, there was only just enough room to get the loaded tub through; the trammers had to crouch and push on hands and knees to avoid splitting their heads open. Besides, the props had already started to bend and split. You could see long, pale cracks running right up the middle of them, making them look like broken crutches. You had to watch out not to rip your skin on these splinters; and under the relentless pressure, which was slowly crushing these oak posts even though they were as thick as a man’s thigh, you had to slip along on your belly, with the secret fear of suddenly hearing your back snap in two.

In passages like these, Zola’s greatest virtues as a writer shine most brightly. Intent on depicting life as he views it, he’s even more committed than Hugo to observing the darkest aspects of reality, no matter how gruesome. These passages are only two examples of numerous moments that, to be frank, outshine the novel’s plot and characters in their raw honesty about the brutality of coal mining and, by metaphoric extension, the capitalist system wherein working people risk their lives and well-being at the behest of the owners who profit from their toil.

Without spoiling the details of the novel’s harrowing conclusion, we must take a look at the novel’s closing passage, which synthesizes the narrative twists and turns into a defiant paean to struggle:

All around [Étienne] seeds were swelling and shoots were growing, cracking the surface of the plain, driven upwards by their need for warmth and light. The sap flowed upwards and spilled over in soft whispers; the sound of germinating seeds rose and swelled to form a kiss. Again, and again, and ever more clearly, as if they too were rising towards the sunlight, his comrades kept tapping away [a reference to the noise of the miners working beneath Étienne’s feet]. Beneath the blazing rays of the sun, in that morning of new growth, the countryside rang with song, as its belly swelled with a black and avenging army of men, germinating slowly in its furrows, growing upwards in readiness for harvests to come, until one day soon their ripening would burst open the earth itself.

No, Zola does not presage the inevitable victory of progress à la Victor Hugo. Instead, he presents a vision of nascent working-class power in the midst of their struggle. Where Hugo views struggle more as means to an end, Zola ultimately seems to valorize working-class insurrection perhaps even more than victory. Such is a Realism-Naturalism worthy of a stubbornly persistent left, whose adherents, in the face of near perennial defeat, so often resort to idolizing the fight rather than the world we seek to build.

“During the Vietnam War, which lasted longer than any war we’ve ever been in—and which we lost—every respectable artist in this country was against the war,” said novelist Kurt Vonnegut in a 2003 interview. “It was like a laser beam. We were all aimed in the same direction. The power of this weapon turns out to be that of a custard pie dropped from a stepladder six feet high.”

It is easy to underplay the power of literature and other forms of art. After all, if art were all it took, then the Vietnam War might’ve ended after Woodstock! But to write off literature as irrelevant to social progress ignores the profound influence novels like these can have on our consciousness, the way even a single encounter with a great book can seem to change everything, can bring something into focus or cast everything you thought you knew in a completely different light. The great James Baldwin said it best:

You write in order to change the world, knowing perfectly well that you probably can’t, but also knowing that literature is indispensable to the world. In some way, your aspirations and concern for a single man in fact do begin to change the world. The world changes according to the way people see it, and if you alter, even by a millimeter, the way … people look at reality, then you can change it.

It may not always be evident, but literature and art can be more than just a falling custard pie. In fact, it could be a vehicle, a conduit to everything we’re missing. We need a book like Zola’s Germinal to paint us a portrait of the brutality of our enemies, to remind us viscerally of the difficulty of the fight for a better world which we may never win but must nonetheless attempt. We also need a book like Hugo’s Les Miserables to remind us why we fight, to re-ignite in us the compassion we have for our fellow human beings and the world we want to build for each other. Sure, it’s a tough sell to imagine that we’d start the transition to socialism if we just mailed a couple of old French novels to 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. But as long as they exist—sitting in bookstores and libraries ready to inspire the hearts and minds of unsuspecting readers, reaching towards a little spot in their brains where they maybe, just maybe, can deposit a little clarity or a little hope—as long as they exist, “books of this kind may serve some purpose.”

Such a stance is particularly ironic given the inclusion of the following passage in his novel: “For everything there is a theory that declares itself to be ‘common sense’; Philinte as opposed to Alceste; mediation offered between truth and falsehood; justification, censure, a somewhat lordly extenuation that, because it contains a mixture of blame and excuse, considers itself wisdom and is often just pedantry. A whole school of politics called ‘the happy medium’ derives from this. Between cold water and hot, this is the party of the lukewarm. In its entirely superficial pseudo-profundity, which analyses the effects without looking at the causes, with its semi-scientific superiority this school condemns public unrest.” ↩

Their name is a pun on the French word “abaissés,” perhaps best translated as “downtrodden” and pronounced in the same way the French pronounce the first three letters of the alphabet. ↩

I’m reminded of a line from one of my great heroes, the writer and journalist Robert Fisk, who opines in the documentary This is Not a Movie that “journalists should be neutral and unbiased on the side of those who are suffering.” ↩