I Have Written a Strange Book About The Future of Artificial Intelligence

‘Echoland: A Comprehensive Guide to a Nonexistent Place’ is both a demonstration and a discussion of the possibilities of transformative new technologies.

Since I was a teenager, I’ve been a fan of utopian fiction, stories that speculate on what a drastically improved world might look like. Although Karl Marx was famously skeptical of “utopian” socialism, I think such works have practical value. By imagining the kind of world we would ideally like to live in, we can see more clearly the work that it will take to get there.

There’s a utopian book from the 19th century that was massively popular in its day called Looking Backward: 2000-1887. The author, Edward Bellamy, declined to call himself a socialist, saying that the term “smells to the average American of petroleum, suggests the red flag, and with all manner of sexual novelties, and an abusive tone about God and religion, which in this country we at least treat with respect.”1 But Bellamy’s vision was profoundly socialistic, as he imagined a world without money, war, poverty, or lawyers. His speculations captivated the American public in his day, with the book selling millions of copies and sparking the formation of hundreds of “Bellamy clubs.” Bellamy’s personal vision for a transformed world was deeply flawed (technocratic, authoritarian), but I think it’s easy to see why his book resonated: it got people thinking harder about their ideals and encouraged debate about how the world ought to be.

At the moment, seemingly everyone is talking about the implications of “artificial intelligence.” I confess to being among those fascinated by new tools like image generators and ChatGPT. I lived through the birth of the internet, but my eerie experiences with some of the new technologies have marked the first time in my life that I have felt truly stunned by a new invention. I have been particularly impressed with image generators—I post the things I get out of them on Instagram.

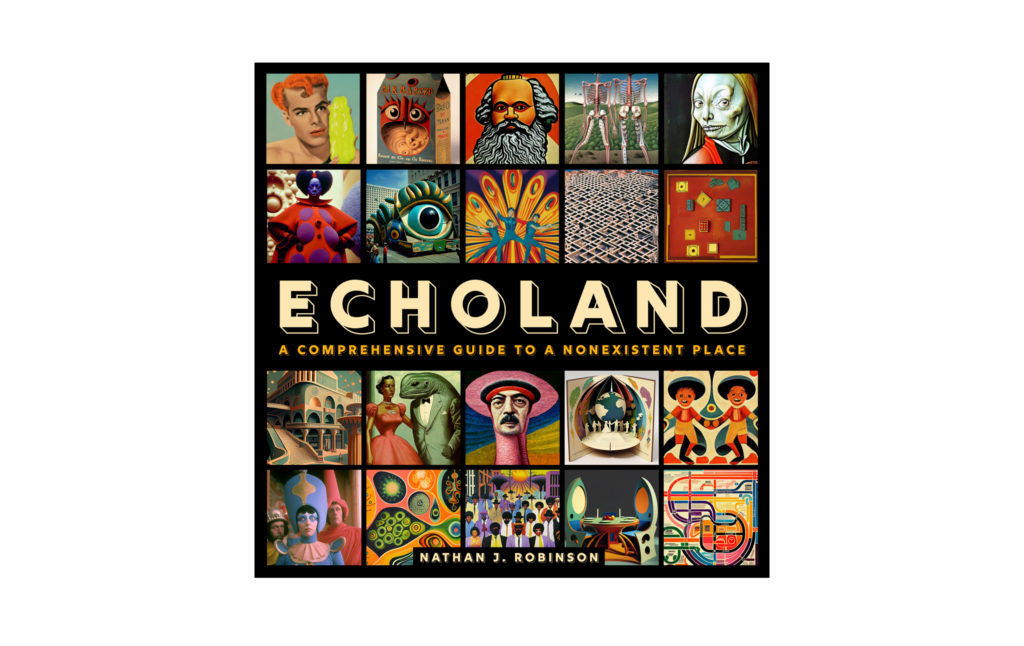

So: I’ve now combined my interest in artificial intelligence with my interest in utopian literature and produced a book I think you’ll agree is quite remarkable. It’s called Echoland: A Comprehensive Guide to a Nonexistent Place, and it is a vision of what a world transformed by “AI” might look like. It’s a kind of updated version of Looking Backward for the 21st century, envisioning a fully automated socialist society where leisure is taken seriously, healthcare is free to all, gender categories have disappeared, and technology is put toward socially valuable rather than destructive uses. It’s a place where deprivation, militarism, and inequality have disappeared. I present a vision of a world where human beings manage to solve their basic problems and invent things that will help them thrive (and take care of the planet). But it’s not a “techno-solutionist” work. Echoland is clear that without being coupled to egalitarian values, new technology can be destructive, and that it is we, not our technology, that must solve our problems.

There’s also a bit of a twist to Echoland, because it’s not just a description of the World of Tomorrow. It also visualizes it in pictures. I’ve used AI image generators to produce imaginary objects from the future society, including train tickets, stuffed animals, and movie posters. I’ve designed clothes and cafes, album covers and textbooks. You’ll find everything in it from Soviet Afrofuturism to “Marx vs. Batman.” The book contains nearly 1,000 AI-generated images, and I’ve tried to demonstrate the remarkable range of capacities that these generators have. I think the results, which it’s often hard to believe were generated by a machine, will surprise you (and may even alarm you a bit).

There are major debates right now over whether what AI image generators spit out is “art” and whether it’s produced ethically. Personally, I have little interest in the definitional question about what “art” is, although I don’t claim to have made art with this book. I do take the ethical questions very seriously, because it’s quite clear that these generators frequently cannibalize artists’ work without their permission and can be used to produce frauds and knockoffs. I certainly don’t think it’s right to use an image generator to imitate the work of a living artist and then pass it off as your original creation. (I care much less about the copyrights of dead artists, which is one reason everything in Echoland has a throwback feel.) But the main problems of AI are actually problems of AI under capitalism; artists are threatened by it because for-profit institutions have an incentive to replace artists with machines when they can. This is a problem of institutional structure, not technology. Here at Current Affairs, which does not have to try to cut costs and make a profit, we can (and have, and will continue to) use AI only to supplement our artists’ work, never to threaten it, and I encourage our artists to go wild with the new tech. As the art director and graphic designer of the magazine, I want artists to use AI as a labor-saving device, rather than having our institution use AI as a cost-saving device, and because Current Affairs is not owned by rich people trying to make money, we can allow for some AI in a way that doesn’t cause harm. (I’ve used it, for instance, to make additional fake ads for the magazine that couldn’t be easily made without the technology, such as this ad for bubble suits.) I hope Echoland demonstrates how these tools don’t have to be used in the service of cruel, capitalistic, anti-artist ends. For me, as a graphic designer, they’re useful as an aid to my productivity.

I’ve tried to make several points in Echoland. The first is that the future doesn’t have to be terrible—but it could be if we’re not careful. In the story I tell, humanity doesn’t reach utopia until after virtually annihilating itself in a nuclear war. But I try to show that civilization-ending calamity is avoidable. A lot of people in my generation are doomers, extremely pessimistic about the prospects for a livable future. I don’t think that’s totally irrational—I share the view of Noam Chomsky that the survival of the species is currently threatened by major human-made crises.

But I also maintain the socialist faith that a better world is possible—we just have to bring it about. Echoland is both a warning and an exhortation. It warns that without a major course correction, we could be heading for a global catastrophe of an unthinkable magnitude. But it exhorts us to take control of our destiny and bring about a future of peace, ecological harmony, and abundance for all. I share the view of philosopher Henry Shue that those alive today have found themselves in a “pivotal generation” that has unique moral responsibilities. Shue thinks we have no less of a moral duty than the generation that had to stop Hitler’s conquest, because if we don’t stop the climate catastrophe, we condemn our descendants to extreme suffering that we have the power to prevent.

A more lighthearted point made in Echoland is that utopia doesn’t have to be boring. When the idea of a “fully automated” society in which people live on a guaranteed income is brought up, I’ve heard it said that such a world would be boring. From this perspective, without work giving “meaning” to life, people would just do nothing all day, which would be bad. For instance, a tech CEO recently tweeted: “One of the reasons I’m so skeptical of universal basic income is that when you run a school you see just how strong the human impulse to not really do anything is. I’m convinced 99% of humans would just watch insane amounts of Netflix and play a lot of video games.”

Now, it’s my own view that even if people choose to watch an “insane amount of Netflix,” that’s no reason not to give them a basic income. (This magazine has published a long defense of laziness, and in Echoland I quote from Paul Lafargue’s 1883 The Right to be Lazy.) I think it would be insane to make people do work that could be automated just because you don’t believe they are choosing the correct forms of leisure and would prefer they go on hikes rather than watching movies. But I also don’t agree that there is some inherent human impulse to “not really do anything.” I think when the options people are presented with are “work or do nothing,” they might do nothing. But in Echoland, I envision a world where people are very active despite not working. They put on huge festivals, they make elaborate costumes, they stage giant games, they build mazes and playgrounds, and they have fun in all kinds of ways that do not involve sitting on a sofa. Of all the arguments against automating unpleasant work, the idea that people will do nothing is one of the silliest to me. First, I don’t care, and second, I think the more people have the capacity to be creative and have fun, the more inventive their forms of leisure will be.

Echoland presents many other points for discussion. I talk about the idea of “centrally planned” and moneyless economies, for instance, and wade into the debate over whether they can function. (Personally I think AI means we need to reopen what is called the “socialist calculation debate.”) Echoland envisions a world where police and prisons have been abolished, replaced with compassionate care for offenders, but it also asks us to consider how much “coercion” is justified to restrain people from doing harm.

I don’t consider everything I present in Echoland to be unambiguously good. Some of it is a little unsettling. For instance, in my story of the future, AI has enabled people to insert dead actors (like Charlie Chaplin) into contemporary movies, and to create realistic interactive simulations of the dead. I am not presenting an entirely perfect world. What I want to do with this book is spark debates over where we’re heading and what paths we ought to take. New technologies threaten to transform society in very unpredictable ways, so I think it’s essential that we try to decide, in a democratic way, what we want out of them, before their development becomes uncontrollable in ways we don’t like. (I’m skeptical of the idea that a self-aware “superintelligent” AI will kill us all, but I certainly think we might use AI to destroy each other. To me, the root of the problem lies much more in ourselves than in our machines.)

Anyway, I hope you enjoy Echoland and that it sparks your imagination. I’m proud of it; it draws together threads from a lot of topics I’ve written about over the years, including dreams, socialism, AI, Mardi Gras, animal rights, education, and so much more. I think you’ll agree that the AI-created images are pretty astonishing (but perhaps not astonishingly pretty). I hope you’ll discuss the book with friends. Ideally, I’d like it to make a constructive contribution to our current debates over the uses of AI. One remarkable aspect of the book is that it’s one of the first books in human history to take full advantage of the design capabilities of our new technologies. It won’t be the best of its kind, but I do think it’s safe to say it’s among the first.

Echoland is available from the Current Affairs online store as a paperback and a digital PDF. It can also be purchased on Amazon as a paperback or a Kindle book.

Incidentally, Bellamy’s cousin Francis was a prominent Christian socialist who wrote the Pledge of Allegiance. ↩