How Queer History Is Buried

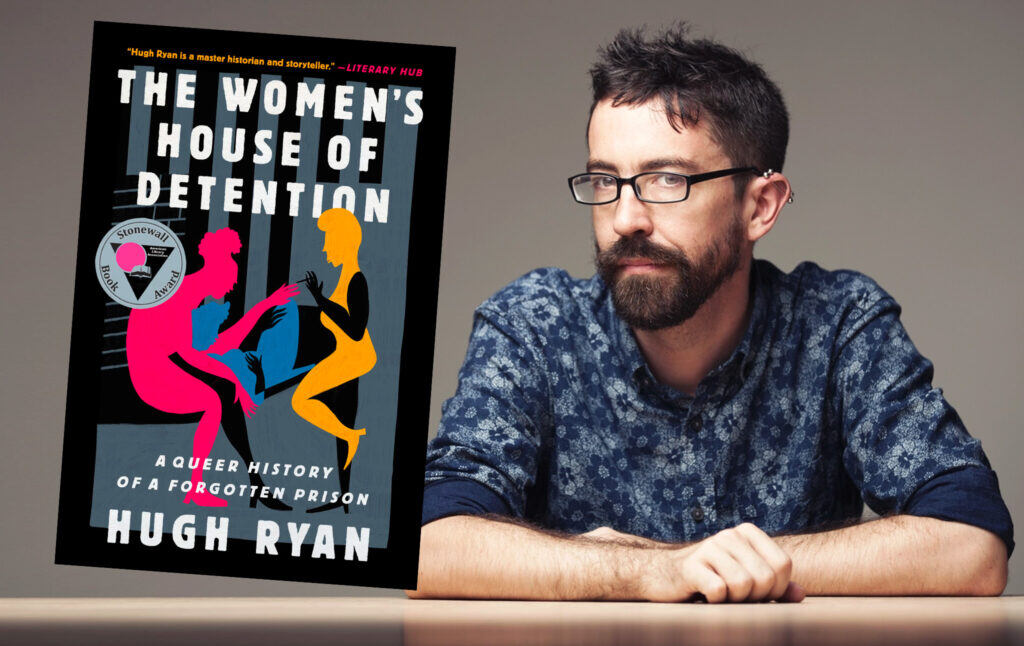

Historian Hugh Ryan, author of “The Women’s House of Detention,” on excavating the stories of LGBTQ+ people from before Stonewall.

Hugh Ryan is a writer and curator who unearths and preserves lost queer history. His books When Brooklyn Was Queer and The Women’s House of Detention (newly released in paperback) both tell stories of LGBTQ life before Stonewall, showing the vibrant and diverse lives of queer people in the United States in the early 20th century that have been left out of history textbooks. The New York Times calls When Brooklyn Was Queer “a boisterous, motley new history… an entertaining and insightful chronicle.” Writer Kaitlyn Greenidge says of Hugh that he is “one of the most important historians of American life working today” and The Women’s House of Detention “resets so many assumptions about American history, reminding us that the home of the free has always been predicated on the imprisonment of the vulnerable.” In this conversation with Current Affairs editor in chief Nathan J. Robinson, which first aired on the Current Affairs podcast, we discuss how important stories get forgotten, and Hugh tells us the story of the Women’s House of Detention in New York City, and why its ignominious history makes a strong case for prison abolition.

Nathan J. Robinson

You excavate queer history, and as I started reading your work, it made me realize the queer history that I was taught in public school probably began in 1969, beginning with the Stonewall Uprising and then progressed from there. What’s so fascinating about your work is where, at least in these two books, the history ends. You go back to all of these stories and worlds that existed in the centuries leading up until the point where queer people became more visible in America in the 1960s. Could you give an overview of what you’re trying to do through these books?

Ryan

The biggest thing I’m trying to do is pay for my expensive archive habit and justifying it by writing books. I love being in the paper stuff of history. But, honestly, the fact that you even learned about the Stonewall Rebellion is a big step up from my public school education in America, where if we learned anything about gay history, it was about AIDS, because it was the 80s. And it was not history, per se; what we were told was there was nothing, and what it was, was awful. There was a blank canvas behind us. If we were to ever dig into it we would hate what we found. That was basically what I learned.

As I got older, I think like many folks from marginalized communities who don’t see ourselves in the world we live in, we look to histories of our own people to understand better our own place in the world, to not feel like a singular freak or someone who makes no sense without history or community. What ended up happening is as I dug in to these histories, I came looking for a mirror to see myself, but that’s not at all what I found. And that is the true beauty of queer history and why I’m devoted to it. I can’t see the future, what’s going to happen next, or how things are going to change. But I can look backwards and very clearly see how over the last 150 years, our ideas—not just about the big picture of gay life, what it means to be a man or a woman, what the body is versus personality, what the brain is—have changed drastically. And that, I think, gives us the possibility of change in the future. I study history because it frees us from believing that our present moment is atemporal, acultural, unchangeable, unbeatable. History allows us to see that change is possible.

Robinson

Could give our listeners and readers an example of one of the changes you’re talking about in our conceptualizations?

Ryan

Absolutely. One that’s really important, particularly in my first book, When Brooklyn Was Queer, but also to the Women’s House of Detention, is the shift at the end of the 19th century into our modern ideas of what it means to be gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and heterosexual as well. Those categories didn’t really exist in 19th century America. If there was an idea of queer identity, it rested around people who were gender transgressors. They might have been identified as inverts or fairies. An invert was a category that combined and collapsed what we think of as being trans, intersex, and gay. It was about not being properly gendered, and assumed it was in your body—that some part of your body was different. It’s a third sex model—America used to run on a third sex model.

And straight people didn’t exist then either, because there was no conception of a sexuality that can be shared by a man and a woman equally. That just wasn’t a thing. It didn’t make any sense to the Victorians. Instead, it was a time of great homo-eroticism and homo-sociality, when men were expected to spend all their time with men, and women were expected to spend all their time with women, write poetry to one another, sleep in the same bed to have physical relationships, which may or may not have been sexual, and may or may not have been erotic, but we’re primary, important, and worth celebrating. And for that reason, what people today would call gender-normative homosexuals probably didn’t even understand themselves as being all that different from everyone else around them. They existed in a different world.

That’s the reason why, in many mainstream histories, it seems gay people appear in the late 19th century and early 20th century. But really, it’s about a breakdown in the Victorian world, which allowed us to understand sexuality as separate from gender, and allowed homosexuality to become a topic of primary importance and an identity we can see in the world. Those behaviors and desires were still there but weren’t constituted as something that mattered, but begins to happen when Freud comes in and tells us the personality is in the brain and urbanize as a country. And suddenly, folks who did not think of themselves as being all that different are beginning to see community with other people in cities—cities like Brooklyn. It’s not that gay people only exist in cities, but that you need a density of people like you to be able to see and imagine yourself as a category at all.

Robinson

Just to be clear, the lack of development of a concept of homosexuality in these times does not mean that it was an Eden of sexual toleration, where what was later considered deviance was considered normal and healthy. Sexual repression certainly existed, but you’re talking about changes in understanding. Talk about how those two things interact.

Ryan

Yes, absolutely. What I’m talking about is identity: how we make knowledge of ourselves based off of our desires, actions, or attitudes. Those things don’t change and have been present at any time. Sometimes they’re oppressed, sometimes they’re allowed, sometimes they’re oppressed in an organized way, and sometimes it’s just incidental. For instance, in the 19th century, there was the category of sodomy. Sodomy was a legal charge, moral issue, and religious issue. Largely, it had to do with violence. Sodomy meant a violent sexual assault that did not include penile vaginal rape. So, this is why all these things fold into sodomy: oral sex, bestiality, child abuse—all of these things come together and are repressed. But there isn’t an identity, the way we think of as, “I am a gay person.”

There are always going to be rules and identities, but change over time are not set in stone. We take the raw material of desire in the body and manipulate it through our culture to produce who we are. And that’s why it can be so different for people in different time periods and places, even for people in the same time and place but in very different cultural communities. It’s not that sexuality, gender, and sex aren’t real, but that everything we do with them is socially constructed.

Robinson

To go back to where we started about the joy of going into archives, one of the astounding things in reading your books and the impression that every reader will probably get is voices from history come alive in these texts one wouldn’t even know had been preserved. You excavate the existing testimonies of these people, who assumedly were silent because they are not mentioned in our textbooks. A good historian can make them speak again, and it’s rather incredible. In the Women’s House of Detention, you’re dealing with a population almost never allowed to speak for themselves and never heard, and in this book, you really bring prisoners from the 1920s and 30s alive. People who, as you mentioned at various points, come to us often as data and statistics, with their emotions absent from our understanding of who they are.

Ryan

I’m a firm believer that there is much more in the archives and records than have ever been brought to light, for many different reasons. I think some of it has been buried by people who are homophobic or transphobic, and therefore made it hard to find. I think that sometimes things have been misunderstood. I think sometimes things have been accidentally lost, because there wasn’t the money or infrastructure to preserve them.

So, when I started writing The Women’s House of Detention, that was one of the very first things I realized. Like you said, there is data: our prison and criminal legal system uses people as raw material to create reports and numbers. They’re fungible, not individualized, because their personhood doesn’t matter to the system. I knew I couldn’t write that kind of book. In looking at other books about historical prisons, I knew that finding information from the point of view of formerly incarcerated folks is one of the most difficult things, and even more difficult when it’s queer people, and particularly queer women and trans men—largely people who are poor and people of color. I spent about a year actually trying to imagine where the things I know to exist may appear in the historical record.

I tried early LGBT organizations and periodicals, and the papers of very famous queer people that have been preserved. I found really little about the House of D—I found some things, but not a lot. That meant that I had to sit down and formulate the question: Where do these people end up in the public history and the archives? Because there are two ways you end up in an archive: you have power and are famous; people interview you; you have money, own a home, and your belongings are preserved and passed down to the generation after you; you are a writer and write your own opinions out into the world—all of these ways get you preserved.

The other way you show up in the archive is that you are someone else’s data. So, like we talked about with prisons, someone has power over you and are the ones who preserve these records. Once I thought about that, I began to think about the other places that these women and trans men show up in records where people had power over them, but might be able to get a more realistic view of their lives and get at their own speech through their own writings and photos. I hit on the idea of looking at social workers.

Social workers, particularly in the early 20th century, were very concerned about incarceration, queerness, and female poverty: three things linked together in the late 1800s and early 1900s. These records will have people talking about queer life, because they’re directly related to that existence. These social workers are concerned that these women are queer, because then they will go to jail, or they’ve been in jail and therefore are queer. I was largely right, but it took me a long time to find those files. An organization called the Women’s Prison Association had preserved hundreds of boxes of files dating from the 1930s to the 1960s, and were incomparably helpful in building this book.

Robinson

Let’s introduce, for our listeners and readers, the Women’s House of Detention that is the subject of your book—you call it the House of D. Why this place, where is it, and why have this particular prison the centerpiece of your book?

Ryan

The Women’s House of Detention was a prison in the heart of Greenwich Village, at the intersection of Sixth Avenue, Greenwich, and Christopher Street. If you’re familiar with Greenwich Village today, there’s a large, beautiful library called the Jefferson Marquette Library with a big clock tower on Sixth Avenue that used to be the women’s court. The garden next to it now was formerly a twelve story maximum security prison, which sometimes held upwards of 800 people at a time.

But, it’s not the first prison in Greenwich Village—it’s there for a reason. Prisons have been part of Greenwich Village life since the late 1700s and have been constitutional to the area. When the Women’s House of Detention opened up in the early 1930s, it was because the women’s court was already there. The women’s court acted as a courtroom, not for all arrested women, but for any woman arrested at night in any part of New York City—all five boroughs, not just Manhattan where Greenwich Village is—for prostitution or public intoxication. It was a social responsibility court.

The truth is, women, in general, end up arrested not for violent crimes against people or crimes against property—like robbery or arson—but for crimes against the social order, for being the wrong kind of woman, and for crimes that men almost never get arrested and certainly do not do time for in the way that women do. This prison located in Greenwich Village (starting in the 1930s), with this court (built in the 1910s), aggregates women who are improperly feminine every year up to World War II, up to the most homophobic time in America when gay bars are being raided and people are being arrested on the streets. The city is bringing every improperly feminine woman it can arrest down to Greenwich Village, creating the queer vibe of this neighborhood and helping to define what queerness is for America. Greenwich Village, and San Francisco, became the vision of queerness.

So, this prison is incredibly important. It was, like I said, on Christopher Street, 500 feet away from the infamous Stonewall Inn where the uprising happened in June 1969. The women and trans men in the prison could see Stonewall from some of their windows and participated in the riot. They set fire to their belongings and threw them out the windows while chanting, “Gay rights, gay rights!” They had a riot all their own. But this part of the story of Stonewall, like the prison and the women and trans men who pass through it, has been suppressed, ignored, and hidden at every turn.

Robinson

In both of your books, you seem very interested in the kind of institutional and economic factors that occur in the background that create communities. Communities don’t come together arbitrarily or randomly. There are things done by the state or places where jobs are, factors that people don’t see, that constitute and become very important to the trajectory of queer life in America.

Ryan

Yes, that constituting, those factors, is history. I think we often get taught history as though it were just dates and names and numbers. It’s raw material. It’s like, if instead of math, we just taught counting. History is what comes between those things, how they interact with one another, develop, grow, and change. So much of my work is trying to bring history to sexuality, gender, and identity, our communities, and how we form and devolve—the why, where, and when. It’s to place us within the bounds of history, because so often we’re either presented as not existing, or we’re timeless.

You see all of these gay people projected back into the past as though they had exactly the same thoughts about themselves, the same issues, identities, and ideas as we do today, which, in its own way, removes us from history. We don’t get to grow, develop, or become. We simply are this static and pathetic thing. And that’s not how I see the world. I don’t think that’s true about anyone or anything. We are constantly in change. What I love about looking at history is mapping how these changes happen, how an unexpected thing like a prison opening up in a certain neighborhood can change the very idea of what it means to be queer in America.

Robinson

When you start to understand what came before, it does, as you walk through the world or city, make you realize how ignorant you were before of what produced what you are seeing all around you. Your book opens with a great line about the Market Garden being one of the loveliest places you can’t stand. I love that. I live in New Orleans in a truly lovely neighborhood. I was reading a book the other day about the operations of one of the slave markets, two blocks from the Current Affairs office. There’s no marker and indication that it was ever there. The lives and horrible suffering in this beautiful place has been completely buried. Your whole world changes when you start to understand what produced the landscape that you are now walking through.

Ryan

Agreed. What is so important about this is that it is absolutely and necessarily communal. We have a vision of history we’re often taught that is about the big, famous person who does the thing that changes the whole world—they have a revelation that no one has ever thought and then do something no one’s ever tried to do, and magically, suddenly, we have gay rights. That is the story we get over and over again.

One thing the Women’s House of Detention really clued me into is the gay pioneers that we referenced, the Frank Kamenys and Barbara Gittingses [of the world]—the people who did incredible and important work and had political imaginations that were beyond most people of their time—and over and over again what they say is, “I went to the bars in gay neighborhoods—dirty places, dingy places, many places I didn’t even like all that much, but there I began to understand myself as a human being who has an identity and was oppressed.” It’s the masses of people who are not recognized that actually allow for the ideas our leaders get credit for, and move them forward in important ways.

And often, it is the case that they didn’t have that idea themselves. They may have utilized that idea in the world and promoted it in ways that other people could not. It’s like the radical Black liberation tradition of freedom dreaming, where you have to be in community with one another to imagine beyond white hetero-patriarchy. Otherwise, you’re alone and don’t know what is just you being wrong versus you being oppressed. I was reading about this in the work of the artist, advocate, activist, and incredible all around human Tourmaline. She worked very hard on promoting the idea of the Women’s House of Detention as an important part of history, because she grasps the ways in which the mass of women and trans people who have never been accounted for in our histories of New York City, prisons, queer life, or Greenwich Village are necessarily constituted to all of those things.

Robinson

Could tell us more about the lives of the people who passed through this place? Open the doors and take us inside this institution.

Ryan

Absolutely. They run a very wide gamut. Like I said, I was working on one particular archive, mostly the Women’s Prison Association. They were interested in rehabilitating formerly incarcerated people, and for that reason, worked mostly with folks who were younger, whiter, more feminine, and more educated. And even given that sort of bias to the archive I was working from, there is an incredible diversity of stories of people who pass through the Women’s House of Detention, anything from young women who were arrested in the 1930s because they were truant, runaways, or disobedient to their parents. Disobedience and waywardism laws were pioneered on young women, and could be arrested as a disobedient or wayward at the age of 20. Your parents could actually have you incarcerated without ever having you tried if they felt that you were wayward.

We see this in the case of a young woman named Charlotte, one of the first people I profiled in the book. She was a runaway from Brooklyn, a butch girl who was naturally attractive to other girls. She says at one point, “I didn’t know what homosexuality was. It wasn’t my fault that other young women looked up to me like they would a dazzling football hero.” She gets arrested for running away—her aunt has her incarcerated. In the House of D, in 1936, she meets her first girlfriend, a woman named Virginia who was arrested for murder. Virginia was a mob girl and planned a robbery of a gambling den. The two of them met in prison—very different women with very different outlooks on life and experiences—and fell in love and tried to escape. They reconnected two years later once they were both out and found they actually had absolutely nothing in common. But, the experience of meeting each other helped them to understand who they were. Courts, for many women and trans people in the early 20th century, was the way the idea of homosexuality was spread and where these desires and behaviors got labeled for many of the arrested women and trans people.

On the later end, you get all kinds of women. One of my favorites is Anora, who, in the 1950s, was from a middle or upper class black neighborhood, was very close with her family, had a good job as a key punch operator (kind of like the computer operators from the Hidden Figures movie), and was also a cabaret singer who had cut an album. She was in a butch femme relationship with a butch named Rocky who worked at a toy factory as a supervisor. Anora was so beautiful, cultured, and educated—she had some years of college, as well as a conservatory training. The social workers she worked with were afraid of her. In their notes, they would write things like, “walked carefully around discussing homosexuality so as not to offend her.” That’s not the kind of relationship we expect to see in a 1950s era relationship between a social worker and a formerly incarcerated black woman. It is surprising.

Anora goes on to get involved in early LGBTQ organizing, and eventually leaves the orbit of the Women’s Prison Association and the House of Detention entirely. She tells them very point-blank she’s capable of having heterosexual relationships, but she doesn’t think she will, that relationships with women are just more satisfying. These are stories we don’t expect, because they haven’t been shared, even though they are out there. And if you talk with many queer black people, they will tell you about their elders who have those experiences, but to be caught up in the public record is a different thing entirely. It meant so much to be able to read Anora’s story. Often in letters she had written, things she shared, and in photos, it meant so much to me to be able to see this in a real way. And stories like that continue throughout the book.

For every story I included, there are dozens that I found and did not include, either because there wasn’t enough information about them, were very similar to another story I had already told, or couldn’t figure out how the story ended. This is just a small sliver of the lives that pass through the House of D.

Robinson

Right, and you are still ultimately working within the limits of what was recorded. As you say, you have to be in one of those two situations in order for your story to be preserved. What we have to understand coming away from this is history and human life is so much richer, more diverse, interesting, and strange than then we expected. We’re still only seeing a small fraction of the truth, because we only have what is ultimately recorded.

Ryan

Absolutely. And that’s why in all of my books, I write about the nature of the archives that I’m working with, from both the individual specific archives and, more generally, the process of how these people ended up or didn’t end up in the archives because there is no unbiased archive out there. If tomorrow we all woke up magically disabused of every conscious and unconscious bit of bias we carried with us, we would still be building our histories from asymmetric and often biased archives.

We need to explain to people what the limitations of what we are drawing from, so that our readers can make their own decisions and come to their own thoughts, and also, so we can begin to undo some of this and start to look for archives we have not yet opened up and collections that have not been shared and haven’t been digitized. These records were at the New York Public Library since the 1980s, and as far as I can tell, no queer historian has ever looked at them. Right now, I’m working with a nonprofit organization that has tapes of oral histories with queer people in the 1980s, some of whom born in the late 1800s, that they haven’t known what to do with for decades. These tapes still exist, those stories still matter. They probably matter more than they did when they were made because we don’t have them and waiting for us to figure out ways to share them. No matter where you are, no matter what small town or city, there is queer history waiting to be found and shared.

Robinson

When you put it that way, it makes one excited to study the past. An important aspect of your book on the Women’s House of Detention is it’s also the chronicle of a hideous injustice that was inflicted upon women for decades upon decades. You have pretty strong statements in the book against the use of prisons in general. These people’s lives are important. You tell incredible stories of their coming to discover themselves, their loves and their losses, but also the aspect of something horrific done to many thousands of people that we cannot forget and have not atoned for.

Ryan

Absolutely. I’ve always been progressive and on the far edge of whatever we call the left in this country. But years ago, I would have described prisons as broken and needed to be made better. Looking at it historically showed that it is literally impossible. Once I saw the ways in which this prison did not and could not improve, in both liberal and conservative times, or in times when it was over or under crowded, it was always awful. Once I had that information, it enabled me to read all the brilliant abolitionist thinkers writing for decades at this point—like Angela Davis, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Mariame Kaba—and begin to see the way in which abolition is the only way forward. Getting rid of prisons is a necessary first step—not a far off step, but a necessary first step. Prisons don’t do what most of us think they’re doing, and have very little to do with rehabilitation and justice. In fact, they serve as holding areas for people who have been abandoned by all the other systems that are broken: the education system, welfare system, healthcare system, mental health care system, job training systems, foster care systems, the family—all the places where people, particularly queer people, are often abandoned. Prisons serve as the catch basin for those people we don’t want to take care of in any other way. People we don’t care about, that’s what prisons are for.

Discussions about crime don’t really matter and don’t have an effect on prisons, because it’s not what they’re doing. We all know people who’ve committed crimes, whether it’s running a red light or doing drugs, who have never been sent to prison for it. And yet, many people are sent to prison for those same things, but also because they are poor, Black, lacking in education, masculine, or too feminine. This is the truth that researching prisons shows you: they are irredeemable and will never be fixed. And until we find a new conception of justice, one that isn’t rooted in the late 1700s, we are never going to move forward. Any reform to that system that’s about criminality or legality will be broken immediately by the fact the prison system is still having to serve other broken systems that have not been reformed or fixed.

Once I finished this research, I realized it was the only frame that made sense to understand how queer women and trans people were targeted by prisons decade after decade, and how it did not improve how that history has been hidden and suppressed, how those people have been forgotten, and how these kinds of issues of policing have largely fallen off the queer agenda. It all only makes sense if you start to say that prisons exist to make up for the lack of care in our society. Care and bodily autonomy are really operative pillars around which to build a queer movement.

Abolition gave me a way to see hope for the future of queer people, because abolition asks about who is cared for. And the truth is, in a society like America where we expect care to primarily come from the nuclear family, queer people will always end up uncared for. There will always be children with parents who kick them out, adults without descendants, people who need gender transition services, people with AIDS and need life-saving medications—there will always be queer people who need care. Until we fund care, instead of a giant trap to hold the people we don’t care for, queer people will always be targeted by prisons.

Robinson

In the case of the Women’s House of Detention in New York City specifically, I suppose the implication it could not be reformed is there is an inherent contradiction around the very idea of reforming it. The institution is built, as you say, as a trap—a place where we stick to those we don’t care about. It’s a hellhole built to avoid having to care about those people. The idea that you could reform it is impossible.

Ryan

If we take people we have already defined as disposable or bad—whatever you feel about the criminal legal system, imagine people who are now found guilty by it—and put them in underserved conditions and places that are hard to reach, where few people can see or take care of them with little oversight, and then pay people to take care of them who are poorly paid and trained and often have bad opinions about the very people they’re taking care of, and put them in the middle of nowhere on islands or at the edge of the state border, what is going to happen?

I think we know intrinsically what is going to happen to people in prisons, it’s a no-brainer. We know they’re going to be mistreated. We know, thanks to government studies, that 200,000 people are sexually assaulted in jails and prisons every single year. If we sentenced one-in-twelve people to be imprisoned and raped for their crimes, we would call that barbaric. But when one-in-twelve people we sentence are raped or sexually violated as some kind of collateral damage of their incarceration, we call that justice. How is that possibly a system that can be reformed? You point out that there is some progressive “aspirations” to these kinds of institutions much of the time. Yes, and those reformers often have good intentions, but they accept deals that do not further a decarceral agenda and oftentimes end up, even if they’re minor positive reforms, overwhelmed. People stop paying attention and the system relapses back to cruelty.

Robinson

Out of the stories that you’ve uncovered through your years and years in the archives, what do you wish was told in every textbook? If you could rewrite our public school education to include a couple of things that you’ve discovered, what would you add to American’s knowledge of their history?

Ryan

I don’t know how much I’ve actually discovered. The Women’s Prison Association files I will take credit for. Much of this is a cooperative, collaborative process, with many of us working together and building. In the world today, this process, like every other one for change, is collaborative. It takes time and goals: you have to want to see change in the world for it to happen. Using that lens to look at gender and sexuality, not as permanent moments where I can go back in 300 years and across continents and say, “there’s a lesbian, there’s a trans man,” but to say sexuality and gender are culturally constructed doesn’t mean they’re fake. It doesn’t mean that they’re not dealing with real things in the world, but that they are mediated by everything else and part of our culture—they can change, and you can change them. That’s very important to me.

Along with that, coming off of the Women’s House of Detention book, I think that there is such a need for intersectional analysis of power and how it affects those of us differently depending on where we stand, and how those effects can be multiplied or reduced depending on our own actions. I’m lucky I was a Women’s Studies major in the 1990s. I really came to a political age and adulthood reading Kimberly Crenshaw and Toni Morrison, women of color feminists who taught me about intersectionality, which has helped me see how history really works.

Robinson

One thing I got out of reading your books is even when we think we know history and have become more enlightened and pay attention to some overlooked stories, even when Stonewall is more widely known, 500 feet down the street there may be people behind bars who are still not being heard. There are always more layers to unearth. Every single person approaching these books will discover many things about their city and see things that they never saw before.

Ryan

I like your take-away. I’ll take that take-away, too.

Hear the full conversation on the Current Affairs podcast.