A Personal Reflection on Daniel Ellsberg

Vietnam War veteran and antiwar activist, scholar, and poet W.D. Ehrhart writes about what Daniel Ellsberg has meant to him.

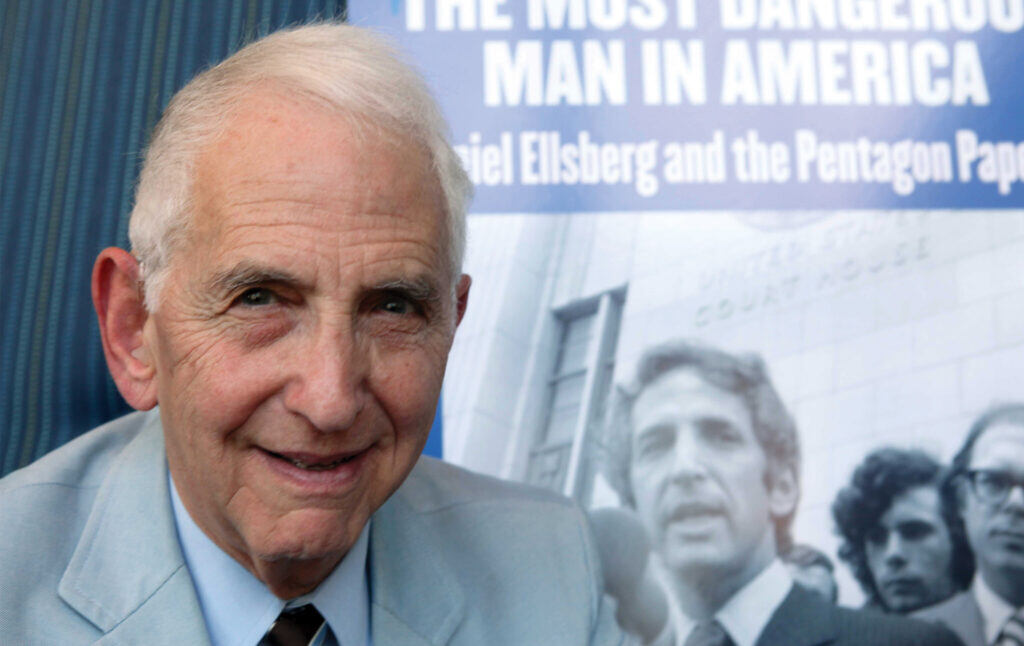

In June 1971, at the end of my sophomore year of college, the Pentagon Papers began to appear in the public domain, first with one newspaper, and when Richard Nixon muzzled that paper, another paper took it up, and then another and another until at last Nixon gave up. Daniel Ellsberg, who risked life in prison to make those documents public, became a hero of mine, a man whose courage and decency have inspired me ever since. This was the man Henry Kissinger had described as “the most dangerous man in America.” (There’s a terrible irony in that, coming from Henry the K, but we’ll not go down that rabbit hole.) The Pentagon Papers permanently changed my life.

Many years later, it must have been about 2002 or 2003—I was teaching at the Haverford School for Boys at the time—I came home from school, and my wife told me that Daniel Ellsberg had called and wanted me to call him back.

Say what?! Who? Seriously?

That was around 2002 and what would be the beginning of a lively friendship between Dan and me by email and telephone. In 2017, he agreed to give the annual Parker History Lecture at the Haverford School, where I was still teaching. He spoke to a standing-room-only public audience in the evening for an hour and a half, without notes, then the next day spoke for nearly as long to 400 students, followed by a Q and A with a smaller group for another hour, and then a lunch for an even smaller group of kids, at which he continued to answer questions. It would have been a marathon performance for any speaker, and this one happened to be 86.

And then I got his email saying that he has pancreatic cancer, and there’s no point in trying to treat it because the end result is inevitable. I certainly can’t say I’m surprised: The man turns 92 in April. I am fully aware that my own place in Ellsberg’s life is very small. But Dan’s place in my life has been monumental.

I enlisted in the U.S. Marines when I was 17 years old. When the Marine Corps sent me to a helicopter base in North Carolina after boot camp instead of Vietnam, I complained repeatedly until they finally did send me to Vietnam.

What I found there was not at all what I’d expected to find. I’ve written about this extensively elsewhere, so I won’t repeat myself here. Suffice it to say that I had expected to be fighting to save the Vietnamese from communism, but instead found myself the modern equivalent of a British Redcoat in the American colonies. I—not the people who were fighting me—was the enemy.

I came back from Vietnam a broken and confused young man, but spent the next two years trying to imagine that whatever the heck was going on in Vietnam no longer had anything to do with me. It was not my problem anymore.

And then in May 1970, the Ohio National Guard murdered four kids—college students like me—at an antiwar demonstration at Kent State University. And when I saw that famous photo of the dead boy and the hysterical young girl kneeling beside him, I finally realized that the American War in Vietnam was still my problem.

And I began to speak out against the war, getting involved in the antiwar movement at Swarthmore College where I was then a first-year student. At local Rotary Club meetings and leafletting war industries like Westinghouse, I argued that the United States had meant well, had tried to do the right thing in Vietnam, but that something had gone terribly wrong and we now found ourselves in an untenable situation from which we had to extract ourselves and get the country back on the right track.

I fully believed that. How could I believe otherwise? And then I read the Pentagon Papers. Here is what I wrote in Passing Time: Memoir of a Vietnam Veteran Against the War about the impact the Pentagon Papers had on me when I was 22 years old:

In late June, thanks to a man named Daniel Ellsberg, the Pentagon Papers found the light of day; I’d bought a paperback copy of the New York Times edition and read it cover-to-cover.

It had been a journey through an unholy house of horrors where all one’s worst fears and darkest nightmares had suddenly become reality, hard, cold, and immutable; where all of the ugliest questions that had first arisen in the ricefields and jungles of Vietnam had suddenly been answered in the starkest and most unmerciful terms; where everything I had believed in for eighteen years and had desperately tried to cling to through four more years of pestilence and famine had suddenly crumbled to ashes—ashes so thick you could hardly breathe, bitter, dry, and suffocating.

A mistake? Vietnam a mistake? My God, it had been a calculated, deliberate attempt to hammer the world by brute force into the shape perceived by vain, duplicitous powerbrokers. And the depths to which they had sunk, dragging us all down with them, were almost unfathomable.

Everywhere I looked, there were ghosts all around me. Ross. Bylinoksi. Murphy. Worman. All dead. Kenny with his arm gone. Gerry with his knee smashed. Captain B with both thigh bones shattered by a fifty-caliber machine gun bullet. Staff Sergeant Trinh with his father dead from a Japanese bullet and his sister dead from a French mine and his mother dead from an American artillery shell and his beloved Vietnam in blistering ruins and his heart broken forever. The forests stripped of their leaves, the fields stripped of their rice, the villages drowning in billowing orange-black clouds of napalm. For what? And the old woman in the ricefield, and the old man on Barrier Island, and the small boy in the market place in Hoi An: dead. All of them dead.

And for what? For what? For a pack of dissembling criminals who’d defined morality as whatever they could get away with. For a bunch of cold-blooded murdering liars in three-piece suits and uniforms with stars who’d dined on fine white porcelain plates while year after year they’d sent the children of the gullible halfway around the world to wage war on a nation of peasant rice farmers and fisherpeople who had never wanted anything but their own country free of foreigners, who had wanted only to grow their crops and catch their fish and live. If only I’d known when it mattered.

Oh, it was all here in the Pentagon Papers. All of it, and much more. Page after page after endless page of it. Vile. Immoral. Despicable. Obscene. Never once in all those years had they questioned their ultimate aims. Never once had they considered that the Vietnamese might not be malleable enough to conform to their blind, willful fantasies. Never once had they told the truth—to me, or to anyone.

I’d been a fool, ignorant and naïve. A sucker. For such men, I had become a murderer. For such men, I had forfeited my honor, my self-respect, and my humanity. For such men, I had been willing to lay down my life. And I had been nothing more to them than a hired gun, a trigger-man, a stooge, a tool to be used and discarded, an insignificant statistic. Even as the years since I’d left Vietnam had passed, even as the doubts had grown, I had never imagined that the truth could be so ugly. Yet here it was—not some rhetorical diatribe from the Weathermen, nor some antiwar pamphlet from the Quakers, but the government’s own account, commissioned by Robert Strange McNamara, secretary of defense for presidents Kennedy and Johnson. Christ in heaven, if there was one single shred of justice left anywhere in the universe, may all their stone-cold bloodless hearts roast in hell forever.

In 2002, Ellsberg had published his memoir Secrets, and in a review of the book, H. Bruce Franklin—who was familiar with my writing—had related the impact the Pentagon Papers had had on me. Ellsberg was on the phone. He wanted to talk with me because he’d never in all those years heard what the impact of his actions had meant to a veteran of the war. We had a pleasant conversation—all the while I’m thinking, “Geez, I’m talking to Daniel Ellsberg! He actually called me up”—a once in a lifetime experience, but the call ended, and that was that.

Years later, in 2015, I opened a conference in Washington, D.C., called “Vietnam: The Power of Protest” with a poem of mine called “Beautiful Wreckage.” The conference was like Space Cowboys of the Anti-Vietnam War Movement. Staughton Lynd was there. Julian Bond (his last public appearance before he died), Barbara Lee, Cora Weiss, David McReynolds, Ron Dellums, Tom Hayden, Susan Schnall . . . and Daniel Ellsberg.

Even before I recited my poem, Ellsberg came up to me and said, “You’re the poet guy, aren’t you? We talked on the telephone once.” I was surprised that he remembered me.

A few months later, I received an email from Ellsberg. He had read a collection of my poems called The Bodies Beneath the Table, and he said, “Terrific book of poetry. I love it! I was thinking I’d mention to you the ones I particularly liked, and then as I leaf through it again just now, I find that it’s nearly every one.

“Right at the beginning, second page, I’m caught by ‘the smell of burning leaves.’ Jeez, I loved that smell. I would have thought you were too young to remember that! Your boyhood, and life, was different from mine. But somehow not that different. Your war, likewise.” He goes on to say that he’s ordered four more books of mine, and closes by saying, “Love, Dan.”

Two weeks later, he wrote again to say, “I’ve just read through The Distance We Travel [my 1993 book of poetry]. Lying in bed, this Saturday morning. Amazing; just amazing. So the war found its Wilfred Owen. Does that, to some small degree, redeem it? No. Of course not. It just means, I guess, that nothing is perfect, not even evil, horror, murder, chaos. Thank you, for what you write, for what you remember. Love, Dan.”

When Dan was writing The Doomsday Machine, he would send me chapters, soliciting my comments. I’m sure he sent this material to dozens of others as well. Nevertheless, Holy Cow!

In 2021, the University of Massachusetts historian Christian Appy invited me to participate in a Zoom conference called “Truth, Dissent, and the Legacy of Daniel Ellsberg.” I thanked him for asking me, but said that I don’t do Zoom because it reminds me too much of Max Headroom, Blank Reg, Bigtime Television, and 20 Minutes into the Future. About 20 minutes later, Dan called and said he’d really like me to participate. That settled that, Max Headroom or not.

In December 2022, I was on a Zoom panel with Dan dealing with the Vietnam War-era antiwar movement as part of the Feinberg Series at UMass-Amherst.

All of this is a wonder to me. It must be what a rookie hockey player feels like when he finds himself on a line with Gordie Howe. Daniel Ellsberg is a giant. A major figure in American history. And a true hero of mine ever since I was 22 years old. That he has made time and space for me in his life speaks to his great heart and generosity of spirit.

The last time he called, to talk about an interview I’d done on the war for Current Affairs, he put his wife Patricia on as well, another first. I’d never spoken with her before. This was maybe a month ago, 2023.

Dan wrote to me:

I feel lucky and grateful that I’ve had a wonderful life far beyond the proverbial three-score years and ten. I feel the very same about having a few months more to enjoy life with my wife and family—[but then goes on to say]—and in which to continue to pursue the urgent goal of working with others to avert nuclear war in Ukraine or Taiwan (or anywhere else).

He then goes on for seven more paragraphs—another full page—to argue the dangers of nuclear holocaust and what we all need to be doing to try to prevent it. “Since my diagnosis,” he writes, “I’ve done several interviews and webinars on Ukraine, nuclear weapons, and first amendment issues, and I have more scheduled.”

This man is terminally ill, facing the end of his life, and yet he is still fully engaged in working for peace and justice, human dignity and decency, and sanity among nations. Incredible.

There will, of course, be a massive worldwide outpouring of appreciation and admiration for Daniel Ellsberg. Already, news of his pancreatic cancer and impending departure from our midst has been reported in hundreds of media outlets from print newspapers like the San Diego Union-Tribune and the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix to magazines like U.S. News & World Report to websites like Common Dreams and The Hindu and Alarabiya News to Reuters, Agence France-Presse, AP, NPR, and PBS, and even off-beat niche sources like California Healthline.

Without the Pentagon Papers, I surely would have lived a very different life than the one I’ve actually had. I might have gone on believing in American Exceptionalism. I might have gone on thinking that any country that opposed the United States of America was wrongheaded and deluded and evil. I might have taken the job I was offered as Project Safety Analysis Coordinator for a nuclear power plant being built by the Bechtel Corporation (employer of Caspar Weinberger and George Shultz, among other luminaries).

So thank you, Dan, for being who you are and for what you’ve meant to me and so many, many others. The world is a better place because you were in it, and will be an emptier place once you are gone. I love you. Farewell.