Godard Without the Politics

American filmmakers have been heavily influenced by Godard’s aesthetic contributions but ignore his radical political messages.

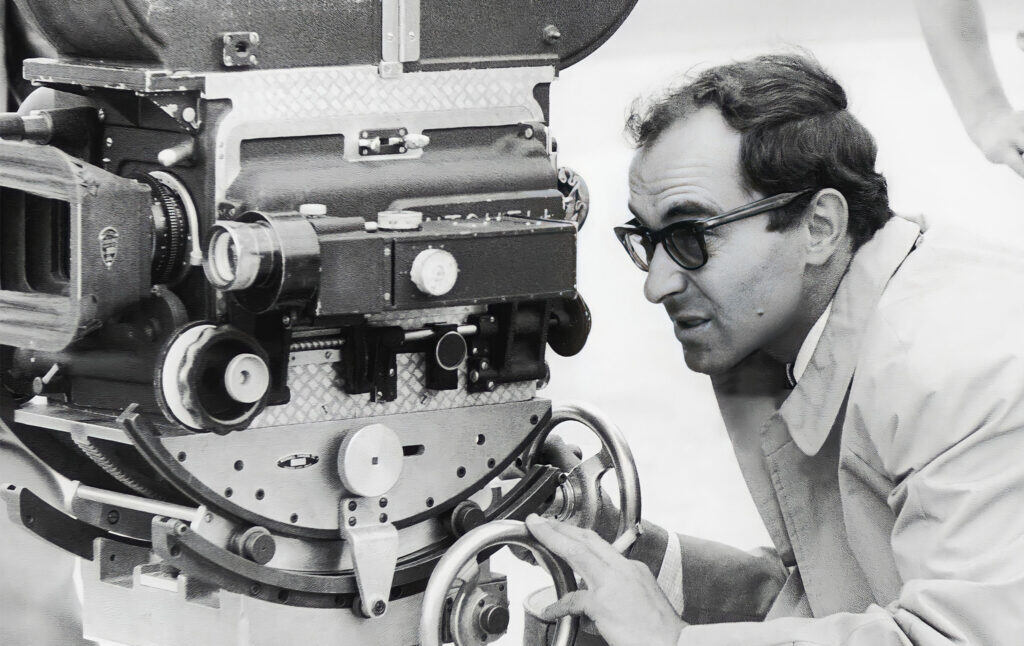

Since the news of Jean-Luc Godard’s death in September of last year, there have been many remembrances published about the tremendous influence he had on the art of filmmaking. As the filmmaker Kelly Reichardt observed in a collection of tributes for The Guardian, “I know what [the late art critic] Dave Hickey means when he says there’s the way the world looked before Andy Warhol and the way it looked after. Isn’t it the same with Godard?”

Film critic Richard Brody, in his 2009 biography Everything is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard, writes that Godard influenced modern filmmakers in two major ways: his innovative cinematic techniques and his unconventional approach to filmmaking. In terms of the former, one can see the enormity of Godard’s innovations in Vivre sa vie (1962) alone. As Brody observes, in that film, Godard invented the “staging of lengthy dialogue scenes in artful framings,” a tactic that can be seen in the “flowing dialogue shots” of Abbas Kiarostami’s 2010 film Certified Copy or the tracking shots of Jesse and Céline in Richard Linklater’s 2013 film Before Midnight. Furthermore, Brody writes, Godard’s use of dialogue as a channel for the director’s thoughts became an essential feature in the work of many American directors, from Woody Allen’s direct-to-camera monologues in Annie Hall (1975) to Quentin Tarantino’s deconstruction of Madonna’s “Like a Virgin” at the beginning of Reservoir Dogs (1992). With both of these innovations, Godard liberated the medium from the stuffy theatricality of classic Hollywood and French cinema, in which dialogue served a purely dramatic function—that is, it operated for reasons internal to the narrative. Today these techniques have become a trademark of virtually “all of the modern verbal American cinema.”

In terms of Godard’s approach to cinema, his influence was more about an attitude towards the conventional way of doing things. As Quentin Tarantino once said, Godard taught him, “the fun and the freedom and the joy of breaking rules … and just fucking around with the entire medium.” That rule-breaking approach is most prominent in Godard’s debut film Breathless (1960). With its mid-dialogue jump cuts, disorienting camera angles, and jazzy editing rhythms, the film was an affront to conventional style that encouraged the next generation of filmmakers to find their voices through their own personal engagements with cinema. In fact, the mere act of calling back to film history (seen in Jean-Paul Belmondo’s Bogart impressions throughout Breathless) or reworking famous images to one’s own artistic ends are Godardian touches that show up in nearly every filmmaker’s work today.1

The early phase of Godard’s career is the most celebrated phase for these aesthetic reasons. Accordingly, remembrances of his work are hopelessly romantic about this phase—from Breathless and Vivre sa vie to Contempt (1963) (about a screenwriter whose relationship starts falling apart when he is commissioned to work on a Hollywood film) and Bande à part (1964) (about a group of English students who plan a small-time robbery).2 As Mike Leigh said of Breathless, “Here was a feast of revelatory challenges to one’s ideas about cinema: pure anarchic bliss!” But appreciations of Godard’s artistry (while welcome) tend to downplay the striking political aspects of his work and the impact they continue to have on many young filmmakers today. As the Canadian actor Kevin McDonald said in the same article Reichardt contributed to, “Those early films still have a daring that takes my breath away. But the later films I have seen are mostly a chore: highly political, highly confrontational—even if sometimes formally inventive.”

In “Not a History Lesson: The Erasure of Politics in American Cinema,” UCLA anthropologist Sherry B. Ortner defines “political” films as those that are “overt” in their political views and primarily concerned with the “dynamics of systems of power.” In this regard, it’s difficult to imagine a more politically charged venture than Godard’s La Chinoise (1967), a film that follows a group of student radicals who spend their summer vacation reading passages from Mao’s Little Red Book and presenting lectures on U.S. imperialism to one another. This film, along with many other Godard films, shows its politics with characters expressing critical perspectives on political issues (as the students of La Chinoise often do, directly to the camera) or in simply foregrounding a topic of political consequence by linking it to the stakes of a narrative (as in La Chinoise when one of the student radicals debates a prominent intellectual on the use of terrorism for political gain).

Godard’s work became more overtly political from 1968-1972, mostly in response to the events of May ’68, a seven-week period of civil unrest that included student occupations and worker demonstrations against the French government and police repression. Brody refers to this time as Godard’s “revolutionary” period, and the wording seems apt considering the projects Godard undertook. A Film Like Any Other (1968) offered some reflections on the worker and student demonstrations of May ’68, while the unfinished Until Victory attempted to cover the Palestinian struggle for independence. Vladimir and Rosa (1971)—whose title is a reference to the Marxist revolutionaries Vladimir Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg—presented a cinematic reconstruction of the trial of the Chicago Eight, the anti-Vietnam War protestors charged with conspiracy and inciting a riot during the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

Certainly, there were many problems with the way Godard handled his political subjects, from his ignorant embrace of Maoism in La Chinoise to his elusive style of communication in Histoire(s) du Cinéma (1989-1999)—a film that at times is so layered in cinematic reference points that it’s basically unintelligible to anyone who doesn’t have a film degree. But there is also something to admire in a filmmaker who takes on political issues rather than ignoring them altogether. It’s an attitude that grounds one’s work in the present and acknowledges its stake in the future of cinema and society. For me, Godard’s “revolutionary” period is the most interesting phase in his filmography, for it exhibits a pivotal deconstruction of his values as a filmmaker. But even Brody, a Godard fanatic, characterizes this “revolutionary” period with some melancholy, as if an artist’s political commitments eclipsing their artistic concerns were necessarily an unfortunate thing:

“With any perspective, the undesirability of the utopia that French Maoists dreamed of seems self-evident; but, unlike other intellectuals, Godard suffered deeply for his engagement on its behalf … had profoundly, even recklessly and enduringly, altered his way of working … having risked and to some extent lost his art for his political commitment.”

Brody’s reduction of Godard’s revolutionary period to artistic misstep is emblematic of a broader tendency in American cinema, namely, a respect for the art that overshadows the relationship of filmmaking to real world political issues. This was an issue Godard himself struggled with as part of the French New Wave, the major film movement of which he was a leading voice and whose political concerns have been similarly overlooked due to its early prioritization of aesthetic merit over everything else.

Emilie Bickerton’s A Short History of the Cahiers du Cinéma catalogs both the aesthetic and political elements of the French New Wave through a history of the magazine that laid its intellectual foundations: Cahiers du Cinéma. Cahiers first gained some notoriety in the 1950s thanks to the contributions of its youngest recruits, which included, in addition to Godard, François Truffaut, Jacques Rivette, and Claude Chabrol (or, as they were more commonly called, the “young Turks”). Their major contribution to film criticism was the politique des auteurs, or “auteur theory,” which elevated the creative status of directors to the central role of filmmaking through careful study of the mise-en-scène—or the deliberate arrangement of actors and objects within a film frame—of several major filmmakers. This focus was radical because of the attention it drew to the style of certain Hollywood filmmakers (notably Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, and Nicholas Ray) at a time when American films were widely opposed by the old guard of French culture. However, as Bickerton’s history reveals, the association between auteur theory and the New Wave is a bit overblown since it only represents the attitude of the movement in its early years and leaves out the many other intellectual threads that came to define Cahiers and its filmmaker offspring.

In fact, despite auteur theory’s persistence in cinema cultures beyond the New Wave, it did not take long for it to become the subject of much criticism in France. On the one hand, the anti-colonial film journal Positif was especially critical of the young Turks’ fixation on compositional analyses of cinema, believing this aesthetic focus was reflective of the group’s failure to take a stance on pressing political issues, like the wars in Indochina and Algeria. Additionally, Cahiers only seemed interested in Hollywood and B-movie cinema, to the exclusion of many groundbreaking surrealist and experimental cinemas around the world—an oversight that gave the whole movement a decidedly conservative bent. Even Cahiers editor-in-chief André Bazin took issue with the central focus of auteur theory and worried that an obsession with specific directors could lead to a dangerous “aesthetic cult of personality” that hindered one’s artistic judgments.

At first, the young Turks were defensive of their theory and stood by its apoliticism, believing that political readings undermined an appreciation of a film’s aesthetic accomplishments. Auteur theory was, after all, concerned less with the subject of a film than with how a subject was handled by a filmmaker in terms of mise-en-scène. Yet it did not take long for the magazine to respond to some of this early criticism. By 1963, under the editorship of Jacques Rivette, the magazine had broadened its focus to include more European filmmakers (e.g., Buñuel, Pasolini, Bertolucci) and “new cinemas” from around the world, like cinema novo in Brazil. Then, a couple years later, under the editorship of two Algerian medical students, Jean-Louis Comolli and Jean Narboni, the magazine increased its engagement with new cinema, moving further and further into explicitly political territory. As Bickerton says:

“[N]ew cinema represented an active resistance to the dominant ideology from its conception, production and reception. … [F]aced with these films, the role of the spectator was elevated to that of an active subject and the film was imbued with the power to provoke social change.”

The adoption of this attitude by New Wave filmmakers was nowhere more prevalent than in the work of Jean-Luc Godard who, after being accused of demonstrating right-wing sympathies in Breathless, took up increasingly political subjects in his work, addressing everything from the Vietnam War to the rise of American cultural hegemony. Thus, very much in rhythm with Cahier’s editorial shifts, Godard’s work became more and more responsive to the political controversies of the day.

To see how this attitude manifested beyond his films, one need look no further than the Cannes Film Festival of May ’68 where, in an archival video of the festival, one can see Godard delivering an impassioned political speech in support of the festival’s cancellation:

“There isn’t one film showing the problems going on today among workers and students. Not one, whether by Forman, myself, Polanski, or François. … We’re behind the times. Our student comrades set an example by getting their heads bashed in last week. The issue isn’t whether or not to see films right now. … The issue is to demonstrate, even if ten days after the fact, the film industry’s solidarity with the student and worker movements taking place in France.”

For Godard, solidarity meant more than this simple verbal endorsement; it meant stealing cameras to lend to protestors to document their demonstrations and taking to the streets of Paris alongside them. It also meant screening his works to student audiences in the U.S., as he did with La Chinoise in Berkeley, and relishing in the impact of his films on the political fervor of those communities.

It’s difficult to imagine an American director today using terms like “comrade” or “solidarity” in an interview or calling for the cancellation of a major media event in light of an ongoing political situation, let alone stealing film equipment to aid political activists. But this kind of act, beyond his aesthetic innovations, is what made Godard significant to so many.

American cinema today has embraced all the aesthetic contributions of Godard, and the New Wave in general, while overlooking all of the ways in which Cahiers, its filmmakers, and its critics responded to the political events of their time. In fact, the more one examines the filmography of the major auteurs working in American cinema today, the more apparent this discrepancy becomes. “Major Auteurs” refers to the elite strata of writer-directors who, despite having the freedom to pursue passion projects within the comforts of the studio system, have been primarily concerned with aesthetic accomplishments and unconcerned with the political relevance of their work. This was certainly true of the first generation of American filmmakers inspired by Godard and the New Wave, which included, among many others, Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas. As Bickerton writes of this group:

“[A]t film school they were ‘taught’ cinephilia in the lecture hall and received a broader cinematic culture from re-runs on televisions. … [E]n masse this generation accepted the terms of the game: earn more with each new film, and tailor the work almost exclusively to please the youth market.”

In other words, while the pivotal generation for modern American cinema embraced the artistic influences of the French New Wave, it also dispensed with the radicalism of its politics by prioritizing market-oriented concerns that enabled their artistic freedom so long as their films continued providing a return at the box office. This apolitical attitude still underlies auteur cinema today and continues to reinforce the assumption that great art is about appeals to universal values via tried-and-true storytelling approaches and the avoidance of politically charged subjects or any renderings of history that reveal how the politics of the past play out in the world today. As Ortner observes, this maxim of the American film industry often manifests in the persistent wisdom that a story is “not a history lesson,” and that there should be a distinction made between what qualifies as “entertainment” and what qualifies as “everything else,” meaning, “not only politics but also educational, informational, and factual materials.”

Look no further than the films of Quentin Tarantino to see this binary at work. Nowhere is the gap between Godard’s cinematic influence and his political influence more apparent. After all, his production company, A Band Apart, is a direct reference to the Godard film of the same name, which makes sense since the film’s influence is all over Pulp Fiction (1994), from Uma Thurman’s Anna Karina bangs (Karina was in several of Godard’s films) to the dance sequence with John Travolta in the restaurant Jack Rabbit Slims. There’s also the especially Godardian touch of innumerable pop culture references, and the bookend story of two lovers holding up a restaurant is reminiscent of Pierrot le Fou (1965). This was Tarantino “fucking around” with the medium.

The remarkable part of this quote comes later though when he asserts, “I consider Godard to be to cinema what Bob Dylan was to music. … I haven’t outgrown Dylan. I’ve outgrown Godard.” The use of the word “outgrown” implies that Godard’s work is somehow less mature than Tarantino’s, which strikes me as rather absurd. Godard’s view of cinema evolved throughout his career, especially as he grew increasingly hostile towards the notion of “entertainment” and ever more conscious of the tradeoffs involved in financing films that he felt a serious political investment in. Tarantino, on the other hand, has yet to “outgrow” the early Cahiers notion of aesthetic mastery over “everything else.” This might explain why his work is more representative of the early Godard than of the later, more militant Godard.

Like the generation of American filmmakers before him, Tarantino accepts the idea that the goal of filmmaking is to entertain. The apparent result of this belief is a politically complacent view of cinema that leads to the valuation of history as escapism in which world-historic atrocities and tragedies become fodder for popcorn revenge fantasies, as in his films Inglourious Basterds (2009), Django Unchained (2012), and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019). In each of these cases, Tarantino uses the period piece genre to take cinematic revenge on the undisputed evildoers of history (which is hardly deserving of a standing ovation). Yet, none of these films attempts to tie their revenge plots to present day political realities, nor are any of them bold enough to examine the historical conditions that produced, say, in the case of Django Unchained, chattel slavery (or reveal that slavery is still legal today in our prisons’ forced labor regimes). Rather, Tarantino’s solution to all of these evils is the same: a good guy with a gun.

The same apolitical and ahistorical bent can be found in the work of his peers, Paul Thomas Anderson and Sofia Coppola. In each of these filmmakers’ oeuvres, universal values—love, family, cultural identity, and so forth—are prioritized over political concerns and historical accuracy. Anderson’s 2012 film The Master is an illustrative example. Set against the backdrop of post-war America, the film is a fictionalization of the founding of Scientology (only referred to here as “The Cause”) that explores the relationship between the church’s charismatic leader, Lancaster Dodd, and a misanthropic veteran, Freddie Quell, who becomes increasingly involved in the church despite his initial reservations about it. Unfortunately, Anderson’s obsession with their relationship, and the chemistry between his leads—communicated through gorgeous and extensive close-ups of Joaquin Phoenix and Philip Seymour Hoffman—comes at the expense of any direct critique of Scientology, or the power dynamics at play between Dodd (the Master) and Quell (his follower). More so, the film romanticizes their relationship despite the abuses it entails without any acknowledgment of the ways in which those same dynamics result in misery for followers of the church today. (A similar fondness for the toxic male patriarch and his love interest can also be seen in the 2017 film Phantom Thread.)

Sofia Coppola’s lack of concern for historical accuracy is apparent in The Beguiled, her 2017 adaptation of a Civil War plantation novel in which a women’s schoolhouse takes in a wounded soldier whose motives seem questionable. The film received a lot of criticism upon its release for whitewashing its Southern setting not only through the absence of enslaved characters, but also in its replacement of the novel’s one mixed-race character with white actress Kirsten Dunst. This deliberate exclusion is in line with the tendency Ortner points to—focusing on the plausible interpersonal drama between the women in the schoolhouse and the wounded soldier who seeks refuge there, over the more historically significant fact of slavery, which does not seem to exist, even peripherally, in the schoolhouse. The Southern plantation, like Anderson’s 1950s backdrop, is just a cinematic device, a gothic skin laid over the drama that betrays the filmmaker’s lack of interest in the political context of the time period. Thus, both films fit a pattern Ortner observes across American cinema: a focus on “interpersonal relationships” that exist in a “social and historical vacuum” and therefore evoke minimal political stakes or consequences in the character’s actions and belief systems.

This trend is not confined to a handpicked selection of auteurs; the pattern extends to the American film industry at large, since politics are as remarkably absent from “auteur filmmaking” as they are from live-action fairy tale remakes, Star Wars prequels, and Minions movies. On the other hand, even when American films do take on politically charged subject matter, they often do so only to affirm existing systems of power. Enter Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises (2012).

In his essay “Super Position,” the late anthropologist David Graeber—while also revealing how “profoundly, deeply conservative” the superhero genre is—reveals how Rises’ depiction of a constituent attack on the Gotham stock exchange essentially aligns the Occupy Wall Street movement with the film’s villain, Bain. Graeber underlines the propagandistic takeaway here:

“Any attempt to address structural problems, even through non-violent civil disobedience [like the Occupy movement], really is a form of violence, because that’s all it could possibly be, … and therefore there’s nothing inappropriate if police respond by smashing protestors’ heads repeatedly against the concrete.”

Thus, sometimes American films aren’t just apolitical; they’re aggressively conservative and disinterested in any perspective that poses a challenge to conditions of the status quo such as income inequality or political corruption. Without a strong corrective from progressive filmmakers who aren’t afraid of bringing political stakes to the fore of their films, social, political, and economic injustices (and their root causes) will remain unchallenged in our collective imagination. As the graphic novelist Alan Moore recently forewarned, the public’s fondness of the superhero genre could be a “precursor to fascism.”

Fortunately, there are a few progressive American filmmakers out there who aren’t afraid to tie their films to present day political issues. Take the more complicated example of Spike Lee and his recent film BlacKkKlansman (2018). The movie is based on the memoir of a Black police officer, Ron Stallworth, who poses as a white man on phone calls with the Ku Klux Klan in order to infiltrate the organization. In his adaptation of this story, unlike Tarantino, Anderson, and Coppola, Lee chooses to remain in the historical markers of his era by drawing attention to the real historical figures and movements of the time, from Kwame Ture and the Black Panthers to David Duke and the KKK. That’s because for Lee, history is not merely a texture. The film feels consequential, grounded not only in the time period, but also in the history of filmmaking and the weight of that history on present day realities. This proclivity is most apparent in a scene in which the Klansmen gather for a screening of D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), the racist epic that has been taught in American film schools for decades due to its influence on film form. Lee uses this scene to remind viewers of the film industry’s grounding in white supremacy, connecting one of the most aesthetically influential (and popular) films of all time with present-day racial inequality and white supremacy. He makes this tie explicit with a rather shocking maneuver at the end of the film as he cuts to footage of the Unite the Right rally that took place in Charlottesville, Virginia in 2017. It’s a jarring transition—from composed big-budget cinematography to shaky news footage of white supremacists marching through Charlottesville—but it’s exactly this contrast that wakes one up as a viewer. And yet, even with the historical and present-day political implications of Lee’s work, there are some notable shortcomings that take root in the film’s prioritization of dramatic concerns over historical accuracy.

As the filmmaker, musician, and activist Boots Riley pointed out, the real Ron Stallworth’s work was part of the FBI’s COINTELPRO, which sabotaged Black radical organizations for years and worked with white supremacist groups to do so more effectively. Thus, the filmmaker’s choice to frame Stallworth as a hero in this story masks the real Stallworth and sacrifices historical accuracy for dramatization. As Riley says, “Without the made-up stuff and with what we know of the actual history of police infiltration into radical groups, and how they infiltrated and directed White Supremacist organizations to attack those groups, Ron Stallworth is [actually] the villain.”

Given Riley’s critique, I think it’s fair to say that, for all its strengths, BlacKkKlansman does not offer a satisfying critique of white supremacy due to the ways that its dramatization rewrites the relationship between white supremacy and state violence. The root of this problem, again, lies in a focus on dramatic values over political ones. The perceived need to create a more likable protagonist results in the taking of fictional liberties, which obscures the otherwise strong political elements of the work. Still, BlacKkKlansman brings the political stakes of its narrative to the fore and ties them to the present day, which is more commendable than simply relegating unsavory truths about race relations to some fictional past for fear of offending its audience with a political point of view. Perhaps this has something to do with the big influence Lee says “My Cinema Hero” Godard had on him.

With the exception of Lee’s work, and that of a few other politically engaged filmmakers, like Boots Riley (Sorry to Bother You), Ava DuVernay (Selma), or Adam McKay (The Big Short), American cinema is remarkably unresponsive to current political issues. It is strange that so many filmmakers who have significant autonomy within the studio system still prioritize filmmaking in which the stakes of the drama are located in interpersonal relationships and historical settings that have little to no grounding in political realities. Godard, on the other hand, always found a way to work with or around the studio system to get financing for films that challenged the status quo. He described this radical approach best when he said, “The problem is not to make political films but to make films politically.”

The final film of his revolutionary period, Tout va bien (1972), is a film that deliberately draws attention to the problem of making films politically as it opens with the rather anti-cinematic image of a hand cutting checks to various film departments (script, cinematographer, music, extras, and so on). In this way, Jean-Luc Godard and his collaborator Jean-Pierre Gorin draw attention to the crude facts of film financing, especially as a voice (offscreen) suggests the filmmakers hire celebrities to get more financial backing, to which the hand responds by cutting another check with the memo, “vedette internationale” (international star). Then the voice asks, “What’ll you tell Yves Montand and Jane Fonda? Actors want to see a story before they agree to anything… usually a love story.” Suddenly, as if it were being pieced together before our eyes, the film cuts to Fonda and Montand walking through a field while affectionately listing off the parts of each other’s bodies—“I love your eyes … your lips … your hands … your knees…” and so on. The whole sequence continues in this manner as the voice continues prompting other story elements into existence: the country, the time period, the characters, their professions, the political landscape, and so on, until the two stars are fully embedded in the central drama of the film: a strike at a sausage factory.

It would have made sense to just start there, centering the audience’s attention on a dramatic conflict as most feature films are wont to do in their opening minutes. Just imagine: Yves Montand and Jane Fonda arrive at a sausage factory to report on a strike, but are immediately detained by the workers, pushed upstairs, and locked up in a second-floor office along with the factory manager. That’s a hook. But instead of grabbing the viewer right away by putting our lovely movie stars in jeopardy, Godard and Gorin opt to foreground their pragmatic reasons for placing movie stars at the center of their examination of a working-class power struggle: money and eyeballs. In a sense, Godard and Gorin are stating their artistic compromise up front so the audience understands what is politically at stake in their work; to make a film centering the working class struggle, they must manipulate the boundaries of the system of power they work within (i.e., the film industry) to their advantage. The result is a multifaceted view of political action, featuring direct reports from the strikers and union representatives and the factory manager, Fonda, and Montand. How many films today can claim this level of overt political consciousness either in terms of content or with an overt critique of the power structures that shape how all films are produced today?

As we reflect on Jean-Luc Godard’s legacy, we must not forget his uncompromising commitment to political action. As filmmakers of the next generation continue developing their voices in the face of unprecedented political challenges—from climate catastrophe to the undermining of American democracy to the rise of fascism around the world to the pernicious influence of surveillance capitalism—we ought to encourage them to adopt more than just the aesthetic innovations of Godard’s work. They should embrace his political consciousness as well. Furthermore, as Godard has demonstrated with films like La Chinoise and Tout va bien, “political” films aren’t categorically devoid of artistry. Politics can shape one’s art just as much as art can shape one’s politics. Filmmakers who infuse political viewpoints into their work have an opportunity to situate themselves in an ongoing narrative of progress and to challenge systems of power in order to make the world and cinema better than the last generation left it. What could be more artistically gratifying than that?

If you enjoyed this article, please support our online work by subscribing to our Patreon ($5 per month, includes exclusive podcasts). Or click here to get our magnificent print edition (6 issues for $69.99) or to make a one-time donation. Current Affairs is 100% reader supported.

Take the Alka-Seltzer tablet dissolving in Travis Bickle’s glass in Taxi Driver (1976), which Martin Scorsese uses as an allusion to an image from Godard’s 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her(1967). ↩

The film is best known for its charming restaurant dance sequence. ↩