There Are No Good Royals

If a member of Britain’s degenerate ruling family doesn’t like attention, he should go away and do something useful with his life.

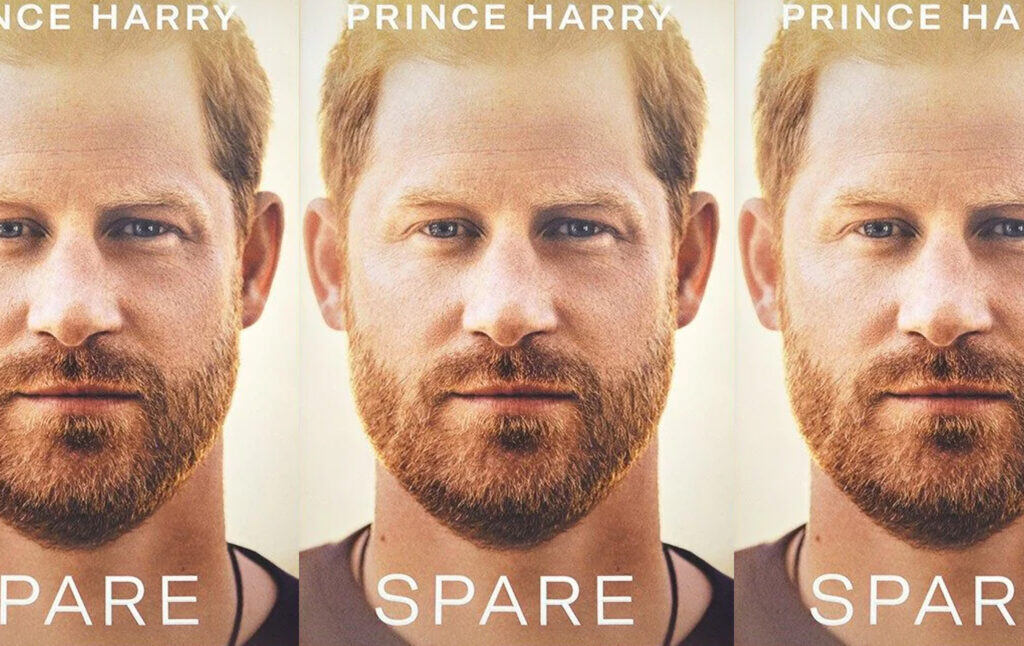

“Prince Harry, Duke of Sussex” (real name Henry Mountbatten-Windsor), a member of the British “royal family” (a small group of ultra-wealthy elites who are inexplicably given lavish support from the state and whose internal personal dramas attract outsized attention), has published a memoir. Alienated from the remainder of the Mountbatten-Windsors, he and the “Duchess of Sussex” (Meghan Markle) are celebrities in the United States, where they do the rounds on talk shows and have starred in a Netflix series. They have attracted public sympathy in part because they seem like comparatively normal people (for being royalty) who have been subjected to vicious coverage in the British tabloid press.1 Suspicious that there can be good, relatable members of the ruling class, I perused the prince’s testimony.

Mountbatten-Windsor’s memoir makes for strange reading, because he didn’t write it, and it’s obvious he didn’t write it. It was ghostwritten for him by an ex-New York Times journalist named J.R. Moehringer, and it overflows with capital-L Literary touches that constantly remind the reader: “You are listening to J.R. Moehringer impersonating Prince Harry, not to Prince Harry, who has merely approved the text.” An example, in a passage about his late mother:

“Maybe she was omnipresent for the very same reason that she was indescribable—because she was light, pure and radiant light, and how can you really describe light? Even Einstein struggled with that one…How could someone so far beyond everyday language remain so real, so palpably present, so exquisitely vivid in my mind? How was it possible that I could see her, clear as the swan skimming towards me on that indigo lake?”

Knowing a ghostwriter wrote the book makes it difficult to be moved even by the parts where our sympathies for Mountbatten-Windsor should be strongest—struggling with his mother’s death, growing up under the harsh spotlight of the tabloid press, living in a family where people speak to each other through press officers and never hug. The reader knows that even the most honest-seeming scenes are a fraud, because they are spoken to us by J.R. Moehringer, who has been tasked with making Henry Mountbatten-Windsor, Duke of Sussex, seem likable.

The whole book feels like it was cooked up as part of a public relations campaign, not terribly surprising coming from a member of a family where the accepted way of settling a score with someone is to have your press officer leak a story about them. The title of the book (Spare) is clever—it is said of royal sons that there is an “heir and a spare,” and Harry is the spare—but it feels almost too clever, as if produced by a team of highly skilled paid professionals tasked with concocting Mountbatten-Windsor’s memoir and conducting the associated media blitz.

Moehringer clearly knows that for his client to win public sympathy, he must appear self-aware, so even as the book is filled with endless references to personal encounters with celebrities like the Spice Girls, Rihanna, and Elton John, it also contains repeated insistences that Harry knows how absurd his life is (as when he is told that to rent a particular swanky Santa Barbara property, he will need to hire a “koi guy” to tend to the “stressed koi” in the pond). There’s plenty of false modesty. (“The cashier tried to thank me…I wouldn’t hear of it.”) And Moehringer finds ways to try to explain away the more sordid episodes in the Duke of Sussex’s life. He once wore a Nazi uniform to a “Natives and Colonials-themed” party because he thought it was “ridiculous” (and also because his brother egged him on), he used the term “Paki” because he thought it was the Pakistan equivalent of “Aussie,” etc.2

Moehringer-as-Mountbatten-Windsor makes sure to acknowledge that the British monarchy “rests upon lands obtained and secured when the system was unjust and wealth was generated by exploited workers and thuggery, annexation and enslaved people.” (When the system was unjust?) Just as “land acknowledgments” have become a fashionable way for elite institutions to buy indulgences, Mountbatten-Windsor’s publicity team cleverly have him make occasional “social justice” noises to help his branding as The Cool Millennial Royal With Values—in this case, acknowledging the unjust foundations of an institution without doing anything to advocate for or alter the distribution of power or wealth..

Still, while Mountbatten-Windsor has broken with the Royal Family, don’t assume he has become an opponent of monarchy. Harry makes it clear that “My problem has never been with the monarchy, nor the concept of monarchy. It’s been with the press and the sick relationship that’s evolved between it and the Palace.” Indeed, Prince Harry’s problems are all personal and have very little to do with general principles. He is upset that he and his wife have been targeted by the press. He isn’t a principled critic of the existence of a ruling family; in fact, he would have enjoyed being part of one, if it weren’t so dysfunctional as to be intolerable.

Spare does show that there are substantial drawbacks to being in the British royal family, for all of the upsides like getting to go and hang out at Elton John’s villa when you’re sad. The Prince had to ask the Queen’s official permission to keep his beard at his own wedding, and his brother tried to royally order him to shave it. All of the royals seem incapable of normal human emotions, and a prince never knows which member of the Queen’s staff is conspiring against him at any given time. (The Queen’s royal dresser at one point plots to keep Meghan from getting to wear one of the Queen’s tiaras.) At one point, the official press officer for Charles (then Prince of Wales, now King) tries to keep Henry’s sister-in-law Kate (Duchess of Cambridge) from being photographed with a tennis racket at a tennis club, because such a photo would upstage a different photoshoot of Charles and his wife. It’s all conniving and plotting, just as it was back in the days when rivals for the throne would lead armies against one another. (In fact, one might respect Harry a great deal more if his response to the slights had been to go off and amass an army to seize the throne, rather than just publishing a dishy ghostwritten memoir and doing a press tour.)

It’s a dysfunctional family. Much of Spare is devoted to airing grievances, mostly against the prince’s brother, William Mountbatten-Windsor (who is Prince of Wales, Duke of Cambridge, Earl of Strathearn, and Baron Carrickfergus). Henry brings up William’s hair loss, recounts a physical fight they once had, partly blames him for the Nazi costume thing, and says that William was unsympathetic when Henry suffered from an attack of agoraphobia. They once had a big tiff over who would get “Africa” as his pet charitable cause, and the Duke of Sussex says the Prince of Wales is obsessive about keeping the “spare” in his place.3

Harry shares everything, including the conversations he has had with his therapist. The effect is somewhat repellent. Harry insists he doesn’t like publicity or the media, but wants to spill all of the ugliest details about his family life onto the printed page and sell them to millions of people. (The book has broken sales records.) He says he believes in “helping others, doing some good in the world, looking outward rather than in.” But the whole book is looking “inward.” Anyone who wants juicy nuggets about the royal family (or amusing little humanizing glimpses of these characters, such as Harry teaching the Queen Mother to use Ali G’s catchphrase “booyakasha”) will certainly get their money’s worth. But if this is what a cool, relatable royal is like, I am more convinced than ever that monarchies must go.

But the book is not just a gossip-fest by an aggrieved flibbertigibbet. It also offers a disturbing look at how those living in a cocoon of privilege can justify atrocities without even realizing that they are doing so. Among all the revelations from the book that made the news, one stood out as different from the others: Harry’s casual admission that he has murdered 25 people.

In the controversial chapter in question, which concerns his time serving the British army in Afghanistan, Mountbatten-Windsor writes:

“I could always say precisely how many enemy combatants I’d killed. And I felt it vital never to shy away from that number. Among the many things I learned in the Army, accountability was near the top of the list. So, my number: Twenty-five. It wasn’t a number that gave me any satisfaction. But neither was it a number that made me feel ashamed. Naturally, I’d have preferred not to have that number on my military CV, on my mind, but by the same token I’d have preferred to live in a world in which there was no Taliban, a world without war…While in the heat and fog of combat, I didn’t think of those twenty-five as people. You can’t kill people if you think of them as people. You can’t really harm people if you think of them as people. They were chess pieces removed from the board, Bads taken away before they could kill Goods. I’d been trained to “other-ize” them, trained well. On some level I recognized this learned detachment as problematic. But I also saw it as an unavoidable part of soldiering…”

Mountbatten-Windsor at one point discusses an incident in which, on a night shift in the operations room, he spots “thermals” of “human forms” on his screen. They are in a “bunker,” and he immediately concludes that the “thermals” are all Taliban. (Because “who else would be moving in those trenches?”) He runs through his Avoiding Collateral Damage checklist, which he stresses is important because this was “a war of enormous collateral damage—thousands of innocents killed and maimed.” (The list runs: “Can you see women? Can you see children? Dogs? Cats?” Bear in mind this is thermal imaging at night.) Seeing no cats, and having determined that the thermal human forms are of the male sex, Harry calls for a 2,000-pound bomb to be dropped on the bunker. His request is denied, and he is offered two 500-pound bombs instead. Not enough, he says. There will be survivors. Harry’s plan is to have the bomb dropped and then order the aircraft to “strafe the trenches running from the bunker, pick off guys as they ‘ex-filled,’” meaning to execute all the survivors as they flee.

Harry does not get his Big Bomb. Instead the 500-pounders are dropped, and sure enough, the bunker isn’t decimated, and some Afghans manage to flee. Harry is disappointed, but reassures himself that the massacre from the skies at least caused a great many deaths:

“Not all of them got away, I consoled myself. Ten, at least, didn’t make it out of that trench. Still—a bigger bomb would’ve really done the trick. Next time, I told myself.”

Mountbatten-Windsor is quick to emphasize that while this attitude—viewing human beings as chess pieces to be “removed”—may sound disturbing, he was not lacking in moral integrity, and “my goal from the day I arrived was never to go to bed doubting that I’d done the right thing.” He operated, he says, out of a deep empathy for the American victims of the 9/11 attacks:

“Not to say that I was some kind of automaton…I never forgot watching the Twin Towers melt as people leaped from the roofs and high windows. I never forgot the parents and spouses and children I met in New York, clutching photos of the moms and dads who’d been crushed or vaporized or burned alive. September 11 was vile, indelible, and all those responsible, along with their sympathizers and enablers, their allies and successors, were not just our enemies, but enemies of humanity. Fighting them meant avenging one of the most heinous crimes in world history, and preventing it from happening again. As my tour neared its end…I had questions and qualms, but none of these was moral. I still believed in the Mission, and the only shots I thought twice about were the ones I hadn’t taken.”

Mountbatten-Windsor’s confession of 25 kills was met with a negative reaction in the press. Some veterans seemed to think it was a violation of some sort of code to discuss the number of victims (one must not be transparent about the costs of war). Personally I am glad he told us the truth, but a spokesperson for the Taliban immediately pointed out on Twitter that even Taliban members are not, in fact, “chess pieces”:

“Mr. Harry! The ones you killed were not chess pieces, they were humans; they had families who were waiting for their return. Among the killers of Afghans, not many have your decency to reveal their conscience and confess to their war crimes. The truth is what you’ve said; our innocent people were chess pieces to your soldiers, military and political leaders. Still, you were defeated in this “game” of white and black “square.” I don’t expect that the ICC will summon you or the human rights activists will condemn you, because they are deaf and blind for you. But hopefully these atrocities will be remembered in the history of humanity.”

If ever you find yourself in a situation where you have ceded the moral high ground to the Taliban, it is time to pause and reconsider your choices. I do not like to say “the Taliban spokesman has a point,” given that his own purported concern with human rights is pure hypocrisy thanks to the Taliban’s atrocious repression and violent misogyny. But there is a certain truth here. Those Mountbatten-Windsor killed were also parents “crushed or vaporized or burned alive.” For Mountbatten-Windsor, the difference is that he was fighting on behalf of the “Goods” against the “Bads.” (As everyone on any side of a war always believes themselves to be doing, since war requires a world without moral ambiguity and in which the enemy is a Satanic pestilence. As Mountbatten-Windsor—okay, fine, I’ll call him Harry—admits, it is nearly impossible to engage in acts of mass killing as he did without dehumanizing people completely and thinking of them as merely the embodiment of Evil, to be exterminated en masse.) Harry acknowledges that there is something “problematic” (a favored term of our era, used to describe everything from rudeness to genocide) about viewing oneself as the embodiment of Goodness while pitilessly killing Evil People as if they were insects. But he does not have serious moral qualms, because of 9/11.

Except: the Taliban were not behind 9/11. As Noam Chomsky and I documented in an exhaustive article on the Afghanistan war, the invasion of Afghanistan was a totally unjustified, illegal war of aggression against an impoverished country. The facts are still endlessly distorted, so let’s get them straight. The 9/11 memorial’s FAQ section, in response to the question “What does Afghanistan have to do with 9/11?”, points out that Al-Qaeda was based in Afghanistan, and explains:

On September 20, 2001, in a speech to a joint session of Congress, former President George W. Bush asserted: “Any nation that continues to harbor or support terrorism will be regarded by the United States as a hostile regime.” No distinction was made between a harboring state and the terrorists it was harboring. The U.S. government insisted that the Taliban immediately hand over the terrorists and close the training camps or face an attack from the United States. When they refused, “Operation Enduring Freedom” was launched on October 7, 2001, less than a month after the attacks of 9/11.

According to Bush, the Taliban “harbored” Al-Qaeda, thus they were just as morally culpable as Al-Qaeda whatever their level of knowledge or involvement in the attacks. In fact, the Taliban immediately denounced the 9/11 attacks, a fact Harry does not mention when he talks about killing to “avenge” 9/11. Bin Laden himself later said that “the Afghan people and government knew nothing whatsoever about these events.” The 9/11 Memorial’s statement that the Taliban “refused” to hand over the terrorists is misleading. What the Afghan government actually said is that it would hand over Bin Laden if evidence of his guilt was provided: “Our position on this is that if America has proof, we are ready for the trial of Osama bin Laden in light of the evidence.” The Taliban “called for an investigation by the United Nations and the Organization of the Islamic Conference into the attacks” and “appealed to the United States not to endanger innocent people in a military retaliation.”

George W. Bush, instead of entering discussions with the Afghan government on how to conduct the trial of Bin Laden, began bombing the country. Colin Powell said he had the impression that the president “wanted to kill somebody.” As the Washington Post reported, once it became clear to the Taliban that Bush was going to simply start massacring them if they didn’t meet his conditions, they tried to negotiate with the U.S., but were rebuffed:

President Bush rejected an offer from Afghanistan’s ruling Taliban to turn over suspected terrorist mastermind Osama bin Laden to a neutral third country yesterday as an eighth day of bombing made clear that military coercion, not diplomacy, remains the crux of U.S. policy toward the regime. “They must have not heard: There’s no negotiations.” … Bush’s words were a response to remarks by Afghan Deputy Prime Minister Haji Abdul Kabir, who told reporters in Jalalabad that if the United States halts bombing, “then we could negotiate” turning bin Laden over to another country, so long as it was one that would not “come under pressure from the United States.” Bush has rebuffed similar offers in the past, and administration officials rejected the latest move as a desperation-driven delaying tactic…. “If they want us to stop our military operations, they just gotta meet my conditions, and when I said no negotiations, I meant no negotiations.” … Defense officials had no comment on Taliban claims that U.S. bombing had killed 200 people in Karam, a village in the mountains of Eastern Afghanistan.

Instead of working with the government of Afghanistan to try to arrange the extradition of Bin Laden, Bush simply invaded the country and toppled its government, sparking a decades-long war that ultimately resulted in the Taliban coming back to power and the whole country ending up back where it started (although now with a major starvation problem). Bush didn’t even seem to care much about actually catching the mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, saying in March 2002 that “I don’t know where he is, I just don’t spend much time on it…I truly am not that concerned about him.” Indeed, by that time Bush had turned his attention to his plans for wrecking another country, Iraq.

For Prince Harry to justify killing dozens of people because he was “avenging” 9/11, then, shows that he still doesn’t grasp that he was not, in fact, on the side of the “Goods” in that war. There were no “Goods.” There was a hideous theocracy, and then there was an outside invading force that deposed the theocracy only to install a corrupt and despised replacement, one so unpopular that many in the population became nostalgic for the return of the theocracy. Harry was taking part in a horrible crime that ultimately succeeded at nothing except wreaking further havoc on a country already ruined by decades of war. Harry is right, however, to acknowledge that the killings he took part in were far more to do with vengeance than justice. The United States was furious at the horrible attack that had been committed, and was in no mood for nuanced distinctions between the particular Muslims who committed the attacks and the ones who did not (the former group numbering several dozen and the latter nearly 2 billion). “Terrorist enemies” were everywhere and needed to be wiped out.

Prince Harry shares this homicidal imperial arrogance, exhibited in his clinical discussion of how he dropped bombs on people while looking at a computer screen (while wishing the bombs could be bigger), and his strong assurance that Britain dropping bombs on poor Afghans was unquestionably morally right.

There can be principled princes. One was Prince Peter Kropotkin, who rejected his noble title and became a great anarchist socialist and critic of exploitation. (There is a wonderful biography subtitled From Prince to Rebel.) Harry is not this kind of prince. His book is credited to Prince Harry, and it’s clear that becoming an everyman is not his ideal preference. Despite J.R. Moehringer’s best efforts to make Henry Mountbatten-Windsor sound relatable and humble, he comes across as petty, self-obsessed, and having no interest in “justice” beyond making a few mentions here and there of how much he cares about “mental health” as a cause (having moved on from “Africa”).4

If Henry Mountbatten-Windsor really didn’t want attention, he could stop styling himself Prince Harry and pretending he doesn’t have a last name. (Only the actual Prince can get away with that, since he made a lasting contribution to human culture). He could go off and do good work somewhere. He could genuinely reflect on the harm done by concentrated power and wealth. Instead, Harry seems upset that he can’t have everything he wants. Even his (quite justified) grievance toward the press seems partly motivated by resentment that a prince can be mistreated: “Centuries ago royal men and women were considered divine; now they were insects. What fun, to pluck their wings.” I would not trust this man with power, especially given his casual attitude toward the killing of those he calls “Bads.”

One can have some sympathy for those who grow up in rich families. Wealth fucks you up. It’s not good for the soul. I don’t envy the prince. His mother was taken from him at an early age. His wife has been subjected to nasty racist insults. He does seem unhappy, and I’m glad he sees a therapist. But the best way for him to make peace with his emotional traumas and become a more decent person would be for him to break with the unjust and corrosive institutions of empire and monarchy entirely. It requires a great deal more moral courage and self-examination that J.R. Moehringer shows us in this book.

For instance, a columnist for the Sun newspaper recently wrote that he despises Markle viscerally and “dream[s] of the day when she is made to parade naked through the streets of every town in Britain while the crowds chant, ‘Shame!’ and throw lumps of excrement at her.” This is a particularly extreme and misogynistic example, but the U.K. papers have indeed been consistently vile and invasive in their coverage of the couple. ↩

“I didn’t know that Paki was a slur. Growing up, I’d heard many people use that word and never saw anyone flinch or cringe…” Given his family’s history of using ethnic slurs, I don’t doubt he’s telling the truth about the widespread use of this one. ↩

I do think Harry is doing a service to the cause of abolishing the monarchy by exposing just how human the royal family is. The monarchy rests on the idea that this clan has some kind of superiority entitling them to special privileges and attention. The Queen once had a documentary about her home life banned, in part because by showing her in an “undignified” (i.e., normal) context, it made her seem like everyone else, and thus raised the implicit question of why she should be the Queen at all. Similarly, Harry’s memoir shatters any conception one might have of the royals as superior, making them seem crude and unfit to rule. ↩

Harry is the “Chief Impact Officer” at a life-coaching company. ↩