The Right’s Opposition to Big Tech Is Hypocritical Posturing, But Shows Us How Conservatives Thrive

Right-wing policies are the reason there is unchecked corporate power in the first place. We need to expose the hollowness of anti-tech conservatism and articulate a persuasive left critique of Silicon Valley.

The economic, cultural, and political power of the “Big Tech” giants—a grouping that includes Google, Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and sometimes Microsoft—cannot be understated. These companies are more than just industrial titans: they’re among the most powerful entities, commercial or otherwise, to ever exist. By exploiting a hands-off regulatory environment and a tech-positive political atmosphere, the tech giants were able to form modern monopolies with reaches across almost every sector of the global economy.

As evidence of these companies’ detrimental impact on vulnerable users, economic competition, and workers’ rights has piled up, this political goodwill has unsurprisingly dissipated. Across the political spectrum, calls to rein in Big Tech have become a common rallying cry, leading to the narrative that a “bipartisan consensus on Big Tech” has emerged.

Despite select rhetorical similarities—politicians on the Left and the Right have both argued that these companies leverage their dominant positions to entrench their own power—critiques of Big Tech from the political Left and the Right differ greatly in substance. Progressive critiques of companies like Facebook, of course, center on their monopolistic behavior and disregard for users’ privacy. And Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, for example, has called attention to the harms of corporate concentration.

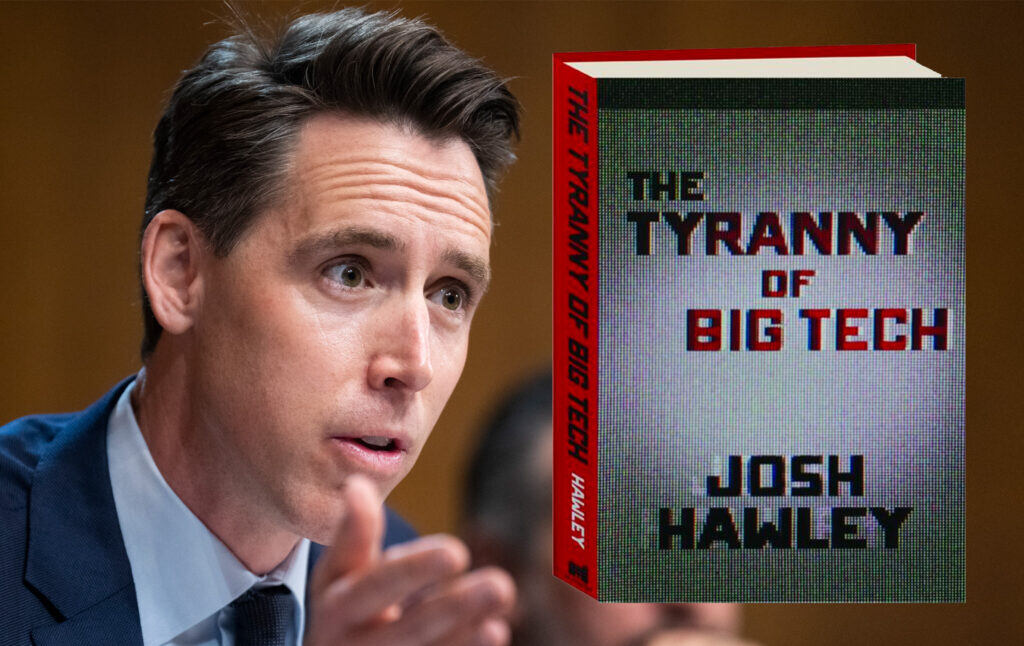

In contrast, conservatives’ anti-Big Tech crusade centers on false claims of ideological discrimination on social media and “election fraud.” (Josh Hawley has even pushed conspiracy theories about Facebook supposedly being unfair to Kyle Rittenhouse.) Despite feigned support for breaking up Big Tech from the likes of Donald Trump, Republicans in Congress and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) have fought against holding Google and Facebook accountable when it actually matters. Indeed, conservatives’ ire at “Big Tech” has often focused on social media platforms like TikTok and ‘pre-Elon’ Twitter, companies that wield wide cultural influence but do not have comparable economic power to the Big Four tech firms.

Though a paucity of survey data makes it difficult to discern the effectiveness of the Right’s messaging, at least some polling shows that it resonates with the public. A majority of respondents in a 2020 survey, for instance, agreed with the notion that “social media platforms are biased against conservatives.” A poll taken in the same year by Pew Research also found that a plurality of respondents believe that large tech companies unfairly privilege liberals over conservatives.

Given that there is no real world evidence to support this claim—and a plethora of evidence that tech barons like Mark Zuckerberg go out of their way to appease conservatives—these results are alarming. From holding private meetings with Tucker Carlson and Ben Shapiro to letting Trump spread misinformation for years, Zuckerberg has worked tirelessly to pander to pander to the Right. In 2018, leaked audio of a Google policy official confirmed that CEO Sundar Pichai had been working to “build deeper relationships with conservatives” out of fear that the company is perceived as liberal. Additionally, internal research from Twitter in 2021 found that their algorithm tended to amplify posts associated with the political right.

But even if conservatives’ victimization narrative had any bearing, they would only have themselves to blame. The truth is that 20th century conservative policies that defanged antitrust gave rise to the Big Tech monopolies of today. Conservatives’ ability to weaponize public outcry over the harms of Big Tech that they’ve enabled reveals an uncomfortable truth: Reactionary politics often functions like a negative feedback loop that feeds off public discontent with problems conservatives helped to create.

Though it may seem odd, conservatives tend to approach tech policy the way they would any other social or economic policy. The pattern in recent years has been to do the following: Take office and gut living standards for the working class at the behest of the wealthy. Then wait a few years for the resulting social dysfunction to arise and run on ‘law-and-order’ to win office again. Destabilize entire regions to the point where people from affected areas have no choice but to seek refuge. Then tell your voter base that desperate people fleeing danger are the real threat.

It’s up to us on the Left to expose this malicious feedback loop—as well as the judicial decisions that paved the way for Big Tech’s power—and to propose real solutions to tech’s numerous societal and environmental harms.

As mentioned previously, the rise of the “digital robber barons” can be traced to the deliberate neutering of antitrust enforcement by conservative jurists. Beginning in the 1960s, right-wing judicial activists like Robert Bork helped distort antitrust law under the guise of promoting “consumer welfare.”

Put simply, the “consumer welfare standard” does not take issue with monopolization as long as a specific merger does not directly lead to higher prices for consumers. As antitrust advocates like Matt Stoller have noted, the CWS deliberately distorts the intent of antitrust legislation while ignoring the impact of mergers on workers and suppliers. Unfortunately, the adoption of the CWS by the courts has weakened the federal government’s ability to clamp down on monopolies, paving the way for extreme consolidation in the tech sector and other industries.

After years of scrutiny, the Department of Justice would in 1998 file a historic antitrust suit against Microsoft for illegally monopolizing the personal computer market. The suit centered on unfair licensing restrictions put in place by Microsoft and the company’s “Embrace, extend, and extinguish” (EEE) strategy to crush competition. Microsoft’s clear-cut anti-competitive behavior was so egregious that even Bork condemned it. Unfortunately, United States v. Microsoft was far from a turning point that would deter future abuses. Instead, the final outcome of the case would set the stage for two decades of inaction on Big Tech.

Even so much as a quick glance at the political environment during this period makes it obvious which party favored the tech giant. While the post-prime Newt Gingrich of today publicly lambasts “tech monopolies,” the Gingrich of 1998 openly cheered on Microsoft while serving as Speaker of the House. In the run-up to the 2000 presidential election, CNN described the prospect of a Republican winning as “antitrust insurance” for the tech giant. During a meeting with Democratic FTC commissioner Dennis Yao, Bill Gates reportedly accused Yao of being a communist for supporting antitrust enforcement.

In the end, Microsoft got the Hail Mary it needed in George W. Bush’s election. During the presidential transition period in 2000, Bush and his allies indicated early on that they were uninterested in holding Microsoft accountable. A year later, Microsoft ultimately got a “big wet kiss from Bush” after the government dropped its bid to break it up.

The rest was history. The sorry conclusion of the Microsoft case created a chilling effect that deterred action against Big Tech for almost twenty years. As noted in a 2018 piece in The Verge, a leading tech publication, “the Microsoft settlement is credited with giving web companies like Google—and browsers like Google Chrome, which overtook Internet Explorer in 2012—space to grow.”

Beyond the browser market, Google would also cement its search engine monopoly during this time, building an empire capable of destroying competitors’ businesses by demoting their websites. Amazon would engage in a predatory “diaper price war” to crush competitor website Diapers.com, taking $200 million in losses in just one month in order to run its opponent out of business. Facebook would begin the buying spree that helped it become the company we know and hate today, while Apple would become powerful enough to implement a de facto 30 percent tax on app developers forced to sell on the App Store.

It goes without saying that none of these monopoly abuses constitute the worst of Big Tech. No one would seriously argue, for instance, that Amazon’s unfair treatment of a diaper startup is comparable to its horrific abuse of warehouse workers. But it’s important to understand how decades of failed antitrust policy led to a situation where companies like Amazon can maintain dominance, even as polling indicates that Americans understand and sympathize with the plight of its workers. Indeed, in a recent article, Amazon Labor Union leader Christian Smalls connected the struggle for better working conditions at company warehouses with the need to improve antitrust enforcement.

Between labor rights, protecting individual privacy, and safeguarding democracy from corporate interference, the struggle to rein in Big Tech is connected to some of the issues progressives hold dearest. When you consider Facebook’s abuse of Kenyan moderation workers and Amazon’s desecration of indigenous land in South Africa, breaking up the tech giants would be a victory against digital colonialism.

And for what it’s worth, there are genuine reasons to object to tech platforms’ opaque moderation policies, including their disproportionately unfair treatment of LGBTQ+ creators. A 2017 investigation of internal documents by ProPublica found that Facebook’s content moderation system is systematically racist and fails to curb Islamophobic hate speech. And Twitter has been known to deplatform leftists well before Elon Musk’s takeover.

But as anyone familiar with Republicans’ actual record on censorship knows, the Right cannot be taken in good faith on this issue. At a time when conservative states like Florida are working overdrive to rob LGBTQ+ people of their right to exist, reactionaries’ expressed concern about freedom of expression online is an obvious sham.

For these reasons and more, the Left cannot afford to cede the issue to reactionaries looking to leverage backlash against industry abuses they’ve enabled at every turn. Ted Cruz, who personally helped Google avoid antitrust scrutiny during his legal career, shouldn’t be able to get away with decrying Google’s corporate power. Similarly, Jim Jordan’s chest-beating about Big Tech should be met with mockery given he went out of his way to oppose a moderate antitrust bill that even 39 Republicans voted for.

Unfortunately, to the extent that the general public does buy the Right’s anti-tech posturing, this kind of hypocrisy will mostly be met with shrugs. With polling showing wide concern about tech platforms’ power across ideological lines, the Left should pounce on the opportunity to present our vision for a digital future free of the harms of surveillance capitalism. If not, we risk letting right-wing extremists in the Republican Party and beyond claim the issue for themselves.

And this ultimately begs the question of what a better, more egalitarian vision for the internet and digital economy might look like. While writer Ben Tarnoff’s remark that “The internet is broken because the internet is a business” has merit on a fundamental level, there are fortunately policy solutions that could help make the internet a better place in the short term.

Recent reports that sensitive information (tax documents and medical records) has fallen into the hands of Facebook stresses the need to pass long-overdue privacy legislation. Mandating algorithmic transparency and stopping the abuse of moderation workers would be strong steps towards ensuring that content moderation systems are accountable and truly work in the interest of public safety. Antitrust enforcement to cut Big Tech down a size would help prevent a future where Facebook controls virtual reality and Apple and Google have turned your car into a ‘smartphone on wheels.’