What I Learned Curating Presidential Theater for Obama

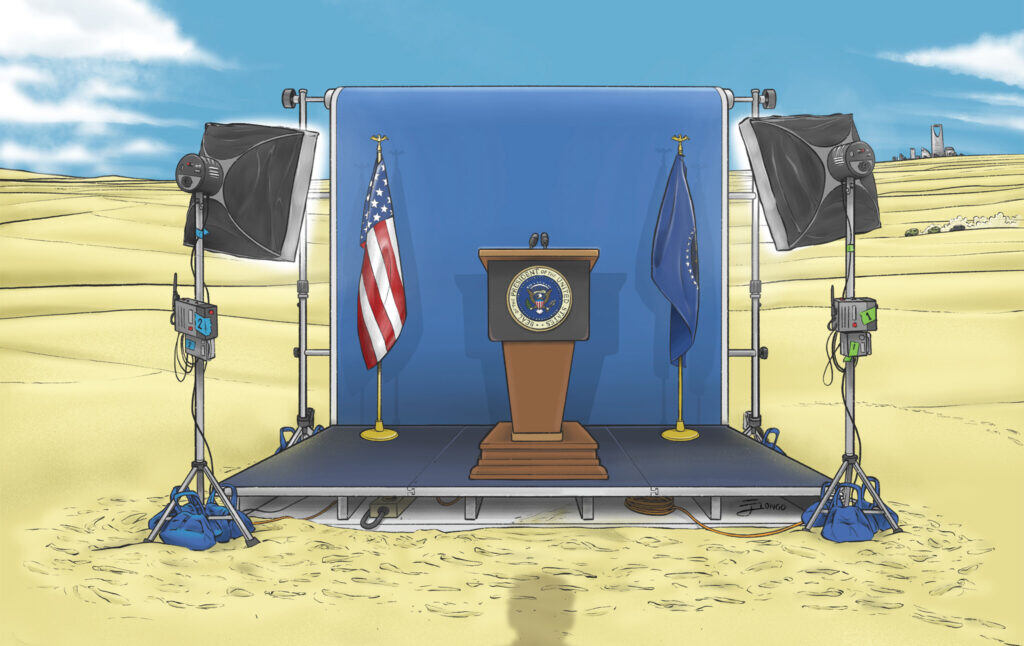

A former Obama advance man on how the hollow pageantry of political stagecraft legitimizes bad policy and distracts us from more substantive political discussions.

We drank and we worried in Saudi Arabia. The drinking was an unexpected comfort. Saudi Arabia is the only place I’ve ever been to where my baggage was sent through X-ray after I got off the plane. This was to ensure I wasn’t sullying the kingdom with booze or porn. It turned out that the Marines who guarded the consulate in Jeddah hadn’t been made to suffer such indignities, however, so they kept the cafeteria well stocked with smuggled alcohol. Nearly every evening, consulate staffers and connected foreign workers would gather there to relax, have a drink, and pretend that, for one night at least, they didn’t live in one of the most socially repressive places in the world.

The worrying, on the other hand, was expected. It came with the job. It was the job. I was on the Obama Administration advance team, and we were responsible for one thing above all else: crafting the image of the President Of The United States and presenting him to the world.

The job of an advance man has been described as a combination of everything from public relations manager and logistics coordinator to carnival barker and personal valet. Each of those descriptions bear elements of truth. When the president or a cabinet official went overseas, we would go out there first, usually about two weeks ahead. From wheels down to wheels up on each trip, we controlled everything, up to and including every step the president or secretary took. We organized the motorcade. We drummed up crowds. We mapped out walking routes: from motorcade, to holding room, to stage, back to holding room, out to press avail, back in for meet-and-greet, depart to motorcade. We carefully designed the backdrop of every speech. We specialized in things like microphones (their appropriate size, shape, and potential phallic resemblance); decorative bunting (is there such a thing as too much?); and doors (should they be open or closed? If the latter, who should open them, and how would that reflect upon the leadership qualities of the trade representative?). We planned every room they walked into and every hand they shook. We knew everyone’s caffeine preferences: tea for the president, cappuccinos for the treasury secretary.

We were, almost uniformly, 20-somethings, unmarried, unburdened with real responsibility back home, and inexperienced in what life was like outside of a college campus. We learned on the job, first lugging campaign banners through the diners and high school gyms of Iowa and New Hampshire, then hopping time zones every five or six days—Pennsylvania, to Florida, to Colorado, and back to Pennsylvania again—as stage managers of a general election in the cable news era. Along the way we racked up Hilton Honors points, drank at every exurban dive that would have us, and hooked up— with each other, with our bosses, and with rally-goers we met on the rope line, handing them autographed copies of Dreams From My Father with phone numbers tucked inside. When we won the 2008 election, we traded in the Hampton Inns of Sandusky and Scranton for the four-star Omnis of Istanbul and Beijing. It was a good life.

But still, there was always the worrying.

Modern political advance work exists in a media ecosystem where the public image of a candidate or official is often given more attention than the substance of their politics. The political reality we lived in at the time was one in which an easily distracted (or worse, lazy) national media would spend significant time discussing the color of the president’s suit, his choice of mustard, and the hand gestures he shared with his wife. It was a media that feverishly covered the president’s State of the Union criticism of the Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling, as if this supposed breach in decorum was just as important as the real-world implications of the ruling itself. It was a media that discussed military deployment policy, but only after it first discussed lapel pins.

With the camera on the president at nearly every minute of every trip, we feared that a mistake by the advance team carried the potential to create viral, administration-defining moments. When Bob Dole fell through an improperly installed security fence at a campaign event in 1996, that was an advance mistake that perpetuated the idea that he was too old to lead. When George W. Bush later tried to exit a press conference in Beijing through a locked door—another advance mistake—the clip followed him for the rest of his presidency, resulting in B-roll that showed him as a goofy, unserious man who was in over his head.

As cultural critic Kiku Adatto, author of the book Picture Perfect: Life In The Age Of The Photo Op, notes, the modern era of presidential stagecraft was, in effect, triggered by the ascendance of a movie star to the White House: Ronald Reagan. Reagan was so successful at creating compelling images that presidential aesthetics became an obsession of the media. According to Adatto, during the 1988 election between George H.W. Bush and Michael Dukakis, “over 50 percent of the network evening news coverage was devoted to talk of photo ops, media events, sound bites, spin control, ads and gaffes.”

We believed, then, that the image of the administration drove its success or failure. Style, essentially, created substance. And so, we always had one thing in mind: we had to ensure that the president looked presidential.

It isn’t exactly clear what the word presidential means. But when it’s used by the media in the context of a campaign or official foreign visit, it’s certainly far more loaded than simply “of or relating to the president.” Instead, it seems to convey an image of an idealized president, as the West Wing-watching, national park-visiting, only slightly politically-engaged voters of middle-class America like to imagine him: competent, compassionate, commanding, and in strong adherence with the American democratic tradition.

And so, when we crafted the images of the Obama administration, our goal was to reflect that idealized vision. We made our bosses appear relatable by putting them on basketball courts in Beijing, farms in Ohio, and the rug of elementary school classrooms in Anacostia. We made them look commanding by crafting Air Force One departure shots and posing them in front of heavy machinery. We composed racially diverse human backdrops, planted volunteers in the crowd to clap in case no one else did, and taped clothes hangers to the back of flag poles so that Old Glory would fall in just the right way: crisp, dignified, but not too stiff. Presidential.

To this end, we tried to control every photograph the president or his cabinet officials appeared in. The shot took precedence over all else. The right shot, we believed, could win an election, pass a bill, or own a news cycle. The wrong shot, we feared, could bring down a presidency.

And this is why, on the ground in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia in the summer of 2009, I was worrying.

I had been in Jeddah a week before Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner was due to land. It was to be the second stop on a major, four-country international tour and, though he would only be spending 23 hours on the ground, we had spent months planning those hours: a televised speech at the chamber of commerce, meetings with a few ministers and the king himself, maybe an “impromptu” visit to something folksy and cultural to show off the secretary’s personality.

And then, on the first day that we woke up in Jeddah, our royal liaison informed us that all of that planning had been for nothing. The king would not be in Jeddah when the secretary landed as we had planned. Instead, he’d be up in Yanbu, a sleepy city on the Red Sea filled with petrochemical factories and the pasty, polo-shirted expats who worked them. The king would be up there to formally inaugurate a series of infrastructure projects, and he’d be taking the rest of the Saudi government with him.

The good news was that we were invited. The king offered us use of a Saudi royal jet to get to Yanbu and promised the secretary a place of honor at the ceremony. The bad news was, well, that the secretary would have a place of honor at a ceremony held by the Saudi king. This was an advance staffer’s nightmare. We didn’t know what exactly the ceremony would look like or entail, but we were familiar enough with Saudi Arabia that we had a pretty good idea. There would be dancing, everything would be gold, and it would take place in a building that might not even have a women’s restroom.

Our biggest fear, though, was that there’d be a medal. In a royal ceremony during the president’s visit to Saudi Arabia the month before, the king awarded Obama with the King Abdul Aziz Order of Merit. Pictures soon circulated of the president bowing his head in front of a man wearing a thawb and posing with something that looked like pirate treasure around his neck. The advance team hadn’t known it was going to happen, a mistake that may have fueled the then small but growing claim amongst right-wingers that Obama was secretly Muslim.

Our second-biggest fear was that one of the factories the king would be opening would turn out to have been built by the Bin Laden family’s mammoth construction company. The family was omnipresent in Saudi Arabia and had loudly disowned their infamous son, but we knew such nuance would be lost once cable news started shouting about it. It was possible that we’d be feeding Fox News a summer’s worth of stories about Tim Geithner personally funding Al-Qaeda’s purchase of a suitcase nuke.

Each day we woke up in a Saudi government hotel that was completely empty of guests except for our staff. We drove in armored cars to the consulate and then immediately hopped on one conference call after another with the team back in D.C., worrying about all the ways the king could make us look bad, all the ways in which the wrong shot could derail a policy agenda. We considered canceling the entire trip. We briefly hoped that the Secret Service wouldn’t allow us to fly on a Saudi jet so we could duck out of the whole thing while citing security concerns. We debated whether we could go to Yanbu, but hide in a backroom somewhere during the ceremony.

We nursed smuggled beers in the cafeteria of the consulate and worried about all of the weird, embarrassing, politically-damaging photographs that might come out of this trip.

Eight years later, though, another U.S. president would visit Saudi Arabia. During his trip, he would take part in a gaudy, embarrassing ceremony hosted by the Saudi king. And this trip to the desert would belie almost everything I thought I understood about American politics.

Few public figures (and certainly no presidents) have so consistently looked like a clown the way Donald Trump has. The shots are there, in our browsers and brains forever. There he is, throwing paper towels to people in Puerto Rico who had just survived Hurricane Maria, a Category 4 storm. There he is, shoving the prime minister of Montenegro to get to the front of a photo. There he is, saluting a general of one of America’s sworn enemies in North Korea, asking a 7-year-old whether she still believes in Santa, taking a Sharpie to a weather map, joking to Boy Scouts about having sex on a boat, signing blank pieces of paper in the hospital, needing help to walk down a ramp. This fucking guy—so vain, and yet so bad at being vain.

Rarely did Donald Trump ever succeed in looking “presidential”—not as the word had been defined by the media, anyway. Frankly, it’s hard to say how much he even tried. Reporting on the 2017 inauguration, the New York Times wrote that Trump had been “proudly unpresidential in word and tweet during the transition.” That behavior, of course, never stopped and, four years later, he was permanently suspended1 from Twitter. And yet, while the media usually covered these gaffes breathlessly, it’s not clear that Trump’s buffoonish, anti-presidential image—and all the media attention he was given—ever really hurt him politically (after all, he received 10 million more votes in 2020 than he did in 2016).

What does that mean? It could be that the job I spent three years of my life doing—all of that political stagecraft I managed—was never nearly as essential as we thought it was. If this is true, then at best it was a harmless frivolity. But it’s also possible that all of that political theater is actively harmful. It’s possible that, not only does the media’s fixation on political theater obscure the more important issues of governance and policy, but that it helped give rise to a president like Trump in the first place.

Consider, again, Saudi Arabia, a particular visit Trump made there, and the way the media completely failed to show the more important story behind the images.

In May 2017, Donald Trump traveled to Riyadh for the first official trip of his presidency, where he attended a summit with government officials from over 50 Arab countries and appeared to reenact scenes from an Indiana Jones movie. You remember the shots, even if you’ve spent the better part of the last 20 months trying to empty your head of the anxiety-inducing memories of that man. He held hands with grown men and danced with a sword. He slept in a hotel that had his own face projected onto the façade. And he gathered with two authoritarian leaders and placed his hands on a glowing orb in what appeared to be an attempt to summon the dark lord of the underworld. It was this last shot that was the big one, the orb leading every late-night talk show and flying around Twitter. Viewers made comparisons to Lord of the Rings and characters from DC Comics and Marvel Universe.

Watching Trump’s Saudi Arabia trip play out was like experiencing my personal advance nightmare come to life. We’ve long exhausted ourselves playing Imagine If Obama Had…, so I don’t need to walk you through the right-wing outrage that would have crashed your Facebook feed if Obama had so enthusiastically cosplayed a Bond villain. Hell, we don’t even need to imagine it. When Obama accepted the aforementioned medal from the Saudi king, some on the Right declared it an unconstitutional violation of the emoluments clause, which none of us had even heard of at that point. But I also know what would have happened to me had I been the advance man who, hypothetically, had allowed Obama to appear in any “orb”-like footage, which gave anyone an opportunity to call the president Muslim, a globalist, and a lover of America’s kaffiyeh-wearing enemies: I would have been fired. (Of course, this probably also speaks to the double standards of presidential optics for Obama, the first Black president and a man whose middle name is Hussein.)

The shots of Trump and the orb were everywhere, and it wasn’t just the late-night hosts who were fixated on them. The New York Times, Washington Post, and the Guardian all ran articles specifically about the orb the next day. A group of Nordic heads-of-state would mock Trump later that week by placing their hands on a soccer ball. And years later, in a retrospective of the Trump administration, the Atlantic would call it one of the most iconic presidential photographs in history (not in a good way, of course. The author said the photo was an example of the British word naff, which means vulgar or demonstrating lack of taste).

What received significantly less attention, though, was the actual substance of the summit. Other than the record-setting $460 billion arms deal between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia, there wasn’t much reporting about what was actually discussed and agreed upon in Riyadh, as many news outlets focused on the pageantry. Even the arms deal was met with a relative yawn. (If there’s one constant of American foreign policy, it’s that we love giving people guns.) This is significant, though, because while the U.S. and Saudi Arabia have always maintained an awkward alliance, U.S. foreign policy had been trending away from the Saudis’ favor for much of the 21st century. This culminated with Obama’s denuclearization deal with Iran, which the Saudis strongly opposed on the basis that it would allow Iran to eclipse them for regional power.

So, looking back on the orb summit in the context of the events that followed, it’s now surprisingly easy to see it for what it was: a money and arms-fueled remaking of the Middle East in Saudi Arabia’s image. This summit was the moment when Mohammed bin Salman (MBS)—then just another Saudi prince, but now described by some as the “most powerful leader in the Middle East” or the “power behind the throne” of the “world’s leading oil exporter”—purchased American foreign policy from another man, Donald Trump, who wasn’t all that interested in that policy in the first place.

This should be a major scandal, but it plays almost no role in American political discourse today. We apparently don’t have room in the discourse for this. We’ve already gorged ourselves on the orb.

Let’s review what happened.

Just five days post-orb, the Saudi-allied, Sunni-led monarchy of Bahrain began cracking down on its Iran-friendly Shia majority. The royal family banned its principal opposition party, arrested hundreds of protestors, and killed five people during a raid on a sit-in. The timing likely wasn’t coincidental. Earlier that year, Trump dropped the human rights conditions Obama had imposed on arms sales to Bahrain, and, at the orb summit, he met with the king of Bahrain and reassured him of U.S. support.

Two weeks post-orb, the Saudis, joined by Bahrain, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates, emboldened by Trump’s turn toward Saudi Arabia, broke diplomatic ties with Qatar, closed its airspace to Qatari planes, and blockaded Qatar’s only land border (Saudi Arabia itself). The diplomatic crisis nearly escalated into a regional war and continued for several years, as Qatar refused to cede to Saudi demands that it cut ties with Iran and Turkey. Trump, in opposition to his own secretaries of defense and state, and despite the fact that Qatar hosted thousands of American troops on one of the most important military bases in the region, initially voiced support for the Saudis’ actions.

One month post-orb, MBS, who had sent an emissary to Trump Tower in August 2016 with an offer to assist Trump’s campaign, was elevated to crown prince, becoming the de facto ruler of the kingdom. MBS had long been engaged in a Succession-style power struggle with a cousin in which the Obama administration had attempted to remain neutral. Trump called to congratulate him that day. (MBS’s Trump Tower emissary happened to be a convicted pedophile named George Nader, who would later meet with Trump in the Oval Office, but there’s only so much we can cover here.)

Six months post-orb, Elliott Broidy—early Trump supporter, then deputy finance chairman of the Republican National Committee, security contractor, convicted briber, and business partner of George Nader—landed a $600 million defense and intelligence contract with the UAE. Broidy was also working on an even larger contract to raise and maintain a 5,000-strong all-Muslim fighting force on behalf of Saudi Arabia and the UAE, an idea he had sold to Trump during a visit to the White House two months earlier.

Ten months post-orb, MBS, in an interview on 60 Minutes, would express apparent ambivalence about Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. This was a sudden reversal in course, and a departure from longstanding Arab opposition to the recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of the Jewish state, and an effective rebuke of an earlier statement by his own father that such a move would be a dangerous provokation of the Muslim world.

Twelve months post-Orb, Trump, as Saudi Arabia had lobbied for, officially withdrew from the Obama-era Iran nuclear deal, which resulted in the reinstatement of economic sanctions against Iran.

Nineteen months post-orb, Saudi operatives would murder and dismember Washington Post reporter Jamal Khashoggi. Trump would publicly dispute his own CIA’s conclusion that the murder was ordered by MBS.

Twenty months post-orb, Trump would brag to journalist Bob Woodward that he “saved [MBS’s] ass,” by convincing the Republican-controlled Congress not to go after MBS for authorizing the murder of Khashoggi, a U.S. resident and a husband and father.

Twenty-one months post-orb, a congressional report uncovered that on two different occasions, Trump approved the transfer of sensitive nuclear technology to Saudi Arabia.

And finally, 4 years post-orb, the government of Saudi Arabia would invest $2 billion in Affinity Partners, a private equity fund controlled by Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner. The investment was made after the MBS-led board in control of Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund overruled the objections of a due diligence panel that had concluded that Affinity’s operations were “unsatisfactory in all aspects.”

The sequence of events makes it hard to deny what all this means: Donald Trump, in exchange for money and favors, re-oriented U.S. foreign policy toward Saudi Arabia and its allies, allowing them to operate more or less unchecked in the region. Can anyone suggest why this isn’t one of the biggest scandals of the 21st century? It has money! Guns! Pedophiles! And it’s actually pretty easy to unpack: billions of dollars to the president’s family and friends in exchange for letting the Saudis conduct their forever proxy war against Iran (and shooting war in Yemen) without U.S. interference. That’s a hell of a lot easier to understand than whatever Whitewater was.

And yet, again, it’s a mere blip on the national political radar. Does this scandal have a name? Is the nightly news regularly updating you on “SaudiGate”? Are you talking about it with your friends? I’m willing to bet that the answer to each of those questions is no.

But I bet you remember the orb.

The media’s fixation on political theater, “decorum,” and whether a certain candidate or event is “presidential” is letting us all down, obscuring more important, substantive political movements and scandals. “Presidential,” to the media, is an aesthetic concept, not a substantive one. I’m not the first person to take issue with this, and if you’ve ever seen someone sarcastically tweet, “this is the moment that Donald Trump became president,” then you’re familiar with it, too. That now tired but still on-point meme is a reference to the analysis that CNN’s Van Jones provided after Trump’s first joint address to Congress. Trump had invited the wife of a Navy SEAL who had died in a covert operation in Yemen and led the chamber in a standing ovation in the SEAL’s honor. It was political theater, and Jones lapped it up:

“That was one of the most extraordinary moments you have ever seen in American politics, period, and he did something extraordinary. And for people who have been hoping that he would become unifying, hoping that he might find some way to become presidential, they should be happy with that moment. For people who have been hoping that maybe he would remain a divisive cartoon, which he often finds a way to do, they should begin to become a little bit worried tonight, because that thing you just saw him do—if he finds a way to do that over and over again, he’s going to be there for 8 years. Now, there is a lot that he said in that speech that was counterfactual, that was not right, that I oppose and will oppose. But he did something tonight that you cannot take away from him. He became president of the United States.”

Of course, among the things that went unmentioned in Jones’ analysis is that Trump approved the raid that killed the SEAL on bad intelligence, that it was conducted without sufficient ground support, that up to 30 civilians were killed in the raid, that it didn’t even achieve its objectives, that Trump refused to take responsibility for it, and that the deceased SEAL’s own father accused Trump of politicizing his son’s death.

None of that mattered to Van Jones, though. What he cared about was that Trump looked like a president when he said it. He looked, in Van Jones’ own words, presidential.

My own day with Tim Geithner and the Saudi king did not result in any shots of the secretary touching an orb or dancing with a sword; there was no embarrassing news cycle for the administration. We flew to Yanbu on a royal jet staffed by young, conspicuously headscarfless Scandinavian flight attendants (I tried to spot contraband liquor in the drink carts but didn’t see any). We motorcaded down a desert street lined with sword-wielding soldiers in traditional dress. And we spent three hours in a building decorated like an enchantment-under-the-sea-themed prom. There was dancing. There were teams of children singing to the king and thanking him for his benevolence. And there was, for some reason, an old-timey ship’s wheel with a giant red button in the middle of it. A brief video of men in hardhats would play, the king would press his giant red button, and sound effects of a submarine emerging from the deep would fill the ballroom to mark the official opening of one factory after another (some of which may or may not have been built by the Bin Ladens—no one ever did any digging to find out).

It could have been a disaster, with footage passed from one right-wing blog to another. But the secretary never appeared in any shots, and for us, that’s what mattered. We did our job.

So much about the early Obama years now seems impossibly distant, memories of a time that was not just earlier, but fundamentally different, when the phrase “constitutional crisis” seemed like more of an abstract concept than a present reality. Do you even remember who Tim Geithner was? For a couple of months in the wake of the 2008 recession he was on your TV every day, and he’s the only secretary ever to be portrayed in a movie by an actor who has also done a nude scene with a blue, CGI-enhanced penis. But today, so much of that would-be transformational presidency seems to have been blown away by the constitutional hurricane that followed.

And what seems most quaint to me about the early Obama years is just how much we cared about those shots: all that political stagecraft. There I was, taping clothes-hangers to flag poles, while bubbling under the surface of the electorate was a far-right movement that, though it would shortly lead to insurrection, very few people saw coming. Looking back on it now, I wonder whether all that political theater—indeed, whether the entire political media culture that elevates aesthetics—did more than just obscure some of the realities of our politics. I worry that it played a role in bringing about Trump in the first place.

One of the principal, big-picture purposes of all that political stagecraft I managed was to reassure the electorate that the country was stable, that the institutions it relies on were strong, that the people at the top of those institutions were righteous, dedicated, competent servants of the public who just loved stopping at roadside diners for a slice of pie every now and again.

The problem, though, is that people could see that that wasn’t necessarily true. The first 20 years of this century were marked by disastrous, ineffectual governance. George W. Bush, a president who lost the popular vote, was nonetheless installed by a partisan Supreme Court. A terrorist attack was cynically used to start a war in Iraq that almost everyone realized didn’t really have a justifiable basis in fact. A campaign finance law overwhelmingly supported by the public was tossed out and the Super PACs came in. Gerrymandering got worse; Republicans reoriented their party to singularly focus on questioning the legitimacy of the president; 20 schoolchildren were killed in the Sandy Hook school shooting in 2012 and that same bought-and-paid-for party ensured that no effective gun control legislation was passed for years; the Republicans packed the Supreme Court, and the Democrats let them do it; penis size become a topic in a presidential debate.

The institutions that were supposed to hold the country together were cracking apart, and through it all, there I was, putting the president in some pretty pictures, telling America it’s alright, telling them not to worry, telling them that the president’s got this.

Against this backdrop, it’s unsurprising that Trump’s boorishness read as revolutionary to so many of his voters. There’s an element of presidential advance and political messaging that’s inherently dishonest. But the political theater is too obvious, too transparent, and so that dishonesty begets distrust, which begets cynicism, which, apparently, begets people voting for a semi-literate game show host with a face that appears to have been smeared by a melted creamsicle. Why the hell not? The whole system is a joke, anyway. It’s probably not a coincidence, then, that the two most popular national politicians of the last five years (Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump) have been the two who are arguably the least polished. This is the irony of all ironies in Trump’s case, given how much he cares about how he’s perceived, but it’s true, nonetheless.

As long as politicians spend so much time on performative, image-based messaging, and as long as the media focuses so much attention on it, we’re going to struggle to effectively govern the country. It’s a distraction from the more important realities of our politics, and it breeds distrust.

In that sense, we’d probably be better off if, from the presidential advance staff on down, we ditched the political theater and acknowledged the dysfunctional mess of American politics instead of whitewashing it. What if, instead of inaugurating a new president with a multi-day festival reminiscent of a royal coronation, we simply had them sign a four-year contract and get to work? What if, instead of demanding that presidents act as aspirational stand-ins for the whole country, and then making them toss footballs and eat ice cream to prove it, we just demanded that they try to make the country a little bit better? What if we weren’t so conditioned to envision our presidents as granite-chiseled heroes that we elected one who was bald? Or short? Or—gasp!—a woman?

Maybe that wouldn’t have been enough to avert the disaster of Trump. In fact, it almost certainly wouldn’t have, given that the Republican Party, threatened by shifting demographics and unbowed by the judgment of history, isn’t hesitating to turn away from democracy and toward fascism to retain power. But at the very least, we’d be better prepared to face this reality; at the very least, we’d care less about what a president looks like than what a functioning democracy does.

Let’s talk about the American mess with the seriousness it requires instead of distracting ourselves with jokes about an orb. Let’s toss the aesthetics of governance in the trash. Let’s stop the messianic yearning for a president who can save the country through sheer force of all-American will. Then we can banish the word “presidential” forever, or at the very least redefine it so that instead of meaning “looks good standing in front of heavy machinery,” it means “is good at being president.”

Photo: AP

Elon Musk has since reinstated his account. ↩