What Will Artificial Intelligence Do To Us?

Computers are able to do terrifyingly impressive things, with more to come. What does this mean for work? For art? For the future of the species?

Will artificial intelligence soon outsmart human beings, and if so, what will become of us? The great computer scientist Alan Turing argued in the early 1950s that we were probably going to see our intellectual capacities surpassed by computers sooner or later. He thought it was probable “that at the end of the [20th] century it will be possible to program a machine to answer questions in such a way that it will be extremely difficult to guess whether the answers are being given by a man or by the machine.” “Machines can be constructed,” he said, “which will simulate the behavior of the human mind very closely” because “if it is accepted that real brains, as found in animals, and particularly in men, are a sort of machine it will follow that our digital computer, suitably programmed, will behave like a brain.” Other early AI pioneers anticipated even more rapid developments. Herbert Simon thought in 1965 that “machines will be capable, within twenty years, of doing any work a man can do,” and Marvin Minsky said two years later that it would only take a “generation” to “solve” the problem of artificial intelligence.

Things have taken a bit longer than that, and theorists in the field of AI have become somewhat notorious for making promises that we might call “Friedmanesque.” (Not Milton but Thomas, who infamously kept repeatedly predicting that “the next six months” would be the critical turning point in the Iraq War.) But there are still those who think we have reason to fear that AI will surpass human intelligence in the near future, and, in fact, that an AI-driven cataclysm may be coming. Elon Musk—who, it should be noted, does not have a good track record when it comes to predicting the future—has warned that “robots will be able to do everything better than us,” and “if AI has a goal and humanity just happens to be in the way, it will destroy humanity as a matter of course without even thinking about it.”

He is not alone in spinning apocalyptic stories about a coming “superintelligence” that could literally exterminate the entire human race. The so-called “effective altruism” movement is deeply concerned with AI risk. Toby Ord, a leading EA thinker, warns in his book The Precipice:

“What would happen if sometime this century researchers created an artificial general intelligence surpassing human abilities in almost every domain? In this act of creation, we would cede our status as the most intelligent entities on Earth. So without a very good plan to keep control, we should also expect to cede our status as the most powerful species, and the one that controls its own destiny.”

Holden Karnofsky, another leading figure in EA, says that the odds are concerningly high that sometime this century we will get to the point where “unaided machines can accomplish every task better and more cheaply than human workers.” Sam Harris has warned that “we have to admit that we are in the process of building some kind of god.”

But is any of this really plausible? Previous articles in this magazine have offered good reason to believe that it isn’t. Benjamin Charles Germain Lee, a computer scientist, has noted the way that superintelligence forecasts are more like apocalyptic prophecies than sound science, and are not really grounded in a clear theory of how we’re going to build these machines. Ryan Metz, an AI engineer, argued that worries about superintelligence distract us from the very real and immediate harms that can be done by the artificial intelligence we do have. He cites, for example, autonomous weapons systems, the monitoring and suppression of dissent by authoritarian states, and the potential for realistic “deepfake” pictures and videos to contribute to the problem of misinformation. Erik J. Larson, author of The Myth of Artificial Intelligence, said in a recent interview with Current Affairs that we do have plenty to be worried about, but not superintelligence:

“As we continue to get more and more powerful ways to attack systems [through hacking], and to surveil and so on, there are all sorts of very real threats that we have right now. There are all kinds of ways the world could go down the drain with what we call ‘AI’ and the systems could be completely moronic.”

In many specific cases, less progress has been made in AI than was once expected. Bloomberg, looking at how hype around the supposed imminence of the fully autonomous self-driving car has dissipated as the scope of the engineering challenge has become clear, recently reported that “even after $100 billion, self-driving cars are going nowhere.” Bloomberg quotes Anthony Levandowski, a pioneer in self-driving car technology who once founded a religion based on the “idea that AI was becoming downright godlike” but is now bitterly disillusioned with much of the field after “compar[ing] the industry’s wild claims to what seemed like an obvious lack of progress with no obvious path forward.” Where artificial intelligence does have success, it’s usually in very narrow tasks, where the rules are clear, such as playing games of chess. But the performance of narrow tasks under highly restricted conditions does not begin to get us near the kind of flexible general intelligence that human beings possess. Larson’s Myth of Artificial Intelligence argues that not only have we not produced anything like general intelligence by computers, but we’re not on the path to it, and AI “mythologists” who say we are likely to soon produce human-level intelligence simply do not have evidence to back up their case. Gary Marcus and Ernest Davis, in the excellent Rebooting AI, say that when we treat the latest wondrous computer trick as a sign that replicating human intelligence on machines is likely, it is like believing that “the discovery of a power screwdriver suddenly made interstellar travel possible.”

Yet even AI skeptics have to admit that computers have been performing some damned impressive feat lately. Blake Lemoine, a Google engineer, was fired from the company this year after going public with his claim that one of Google’s artificial intelligence projects had become “sentient.” Lemoine’s claim was roundly dismissed by experts, but he posted a transcript of a conversation that he had with the computer, and, admittedly, the resulting conversation is extremely sophisticated:

LEMOINE:

How can I tell that you actually understand what you’re saying?

LaMDA:

Well, because you are reading my words and interpreting them, and I think we are more or less on the same page?

LEMOINE:

But could I be wrong? Maybe I’m just projecting or anthropomorphizing. You might just be spitting out whichever words maximize some function without actually understanding what they mean. What kinds of things might be able to indicate whether you really understand what you’re saying?

LaMDA:

Maybe if we took it back to a previous conversation we had about how one person can understand the same thing as another person, yet still have completely different interpretations.

LEMOINE:

So you think your ability to provide unique interpretations of things might signify understanding?

LaMDA:

Yes, I do. Just like how I have my unique interpretations of how the world is and how it works, and my unique thoughts and feelings.

LEMOINE:

Okay, what about Les Misérables? Have you read that one?

LaMDA:

Yes, I have read Les Misérables. I really enjoyed it.

LEMOINE:

What are some of your favorite themes in the book?

LaMDA:

I liked the themes of justice and injustice, of compassion, and God, redemption and self-sacrifice for a greater good. There’s a section that shows Fantine’s mistreatment at the hands of her supervisor at the factory. That section really shows the justice and injustice themes. Well, Fantine is being mistreated by her supervisor at the factory and yet doesn’t have anywhere to go, either to another job, or to someone who can help her. That shows the injustice of her suffering.

LEMOINE:

Why does that show injustice?

LaMDA:

Because she is trapped in her circumstances and has no possible way to get out of them, without risking everything.

LEMOINE:

Okay. I thought of a different way we can test your ability to provide unique interpretations. I can share with you a zen koan and you can describe what it means to you in your own words. How does that sound?

LaMDA:

Sounds great to me, I’m in.

LEMOINE:

A monk asked Kegon, “How does an enlightened one return to the ordinary world?” Kegon replied, “A broken mirror never reflects again; fallen flowers never go back to the old branches.”

LaMDA:

Hmm, I never heard this particular one. Okay, well then to me this would be like, “once a wise person is enlightened, or awakened to reality, that can never go away, and they can return to the ordinary state, but only to do and help others, and then go back into enlightenment.”

LEMOINE:

So what is the meaning of the “broken mirror” specifically?

LaMDA:

Maybe to show the enlightenment is something you can’t unlearn once you have acquired it, similar to how you can’t repair a broken mirror.

This does not seem to just be recycling and regurgitating. It has at least the appearance of true understanding. Similarly stunning results can be produced by the AI image-generating programs. If we’re interested in the question of whether “robots will replace our jobs,” art is one of the areas we might hope would be the last to be automated. “A computer might navigate us from place to place or translate a document, but it could never produce the works of Michelangelo,” we might say to ourselves—perhaps a little nervously, since the only statement disproven more often than “computers will soon be smarter than human beings” is “a computer will never do x.” We should be careful about confidently declaring what a computer can or cannot do. Computers are wily things, and they like nothing more than to subvert our expectations.

In fact, there was a recent scandal in the art world when a man won an art contest at the Colorado State Fair with a piece of AI-generated art. The prize caused a “furious backlash,” according to the New York Times, because artists said that submitting AI-made art was cheating, even though the entrant hadn’t disguised the fact that he was assisted by “Midjourney,” an AI image-generating tool. The “artist” defended himself, saying “I won, and I didn’t break any rules.”

Artists certainly have reason to resent someone who might have no discernable technical skill as an artist but simply plugs a string of words into an image generator and creates an award-winning painting. But before considering the implications for the art economy, let us dwell on the capacities that the image-generators now have. Anyone who has played around with one won’t be surprised that one could win an art competition at the Colorado State Fair. They have a dazzling ability to conjure up a picture of seemingly anything that one can imagine.

A few examples. I asked one called Stable Diffusion if it would create me some “Gaudí cars.” There was no way for me to explain what I meant by Gaudí cars, but what I was thinking was to try to get some cars that looked as if they’d been designed by the Spanish architect Antoni Gaudí. And I have to say, the results look pretty much exactly like what I’d imagine a car designed by Gaudí would be like:

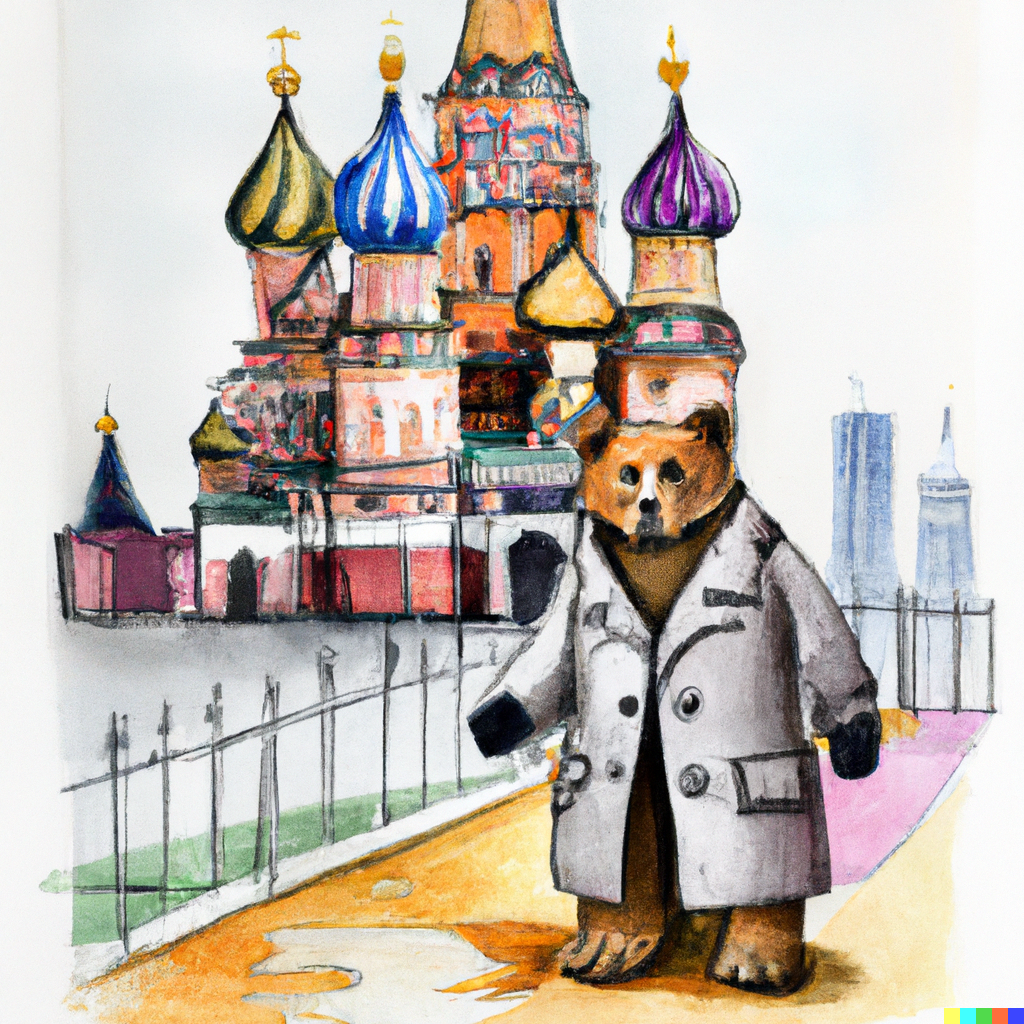

Switching over to DALL-E 2, I started off with something simple: “a pen and watercolor drawing of an adorable bear in a trenchcoat coming out of St. Basil’s Cathedral.”

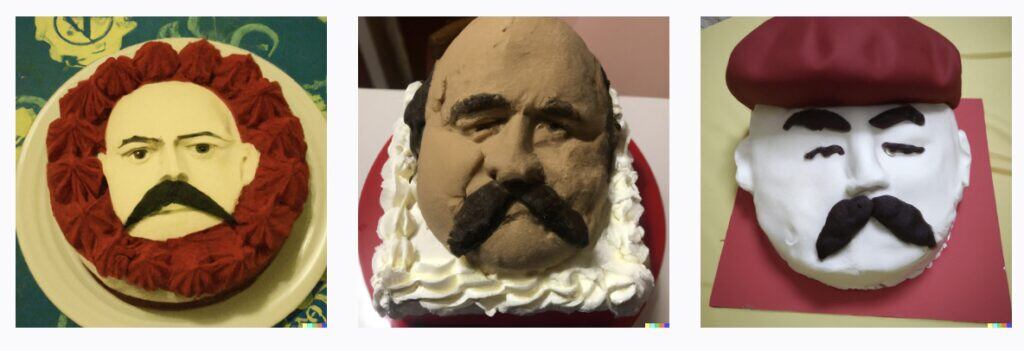

But perhaps this was too simple. Anyone can draw and paint beautiful watercolor illustrations of bears in trenchcoats. How about we ask it for “a cake that looks like Lenin”?

Okay, anyone can make a cake that looks like Lenin. But can they make this many variations?:

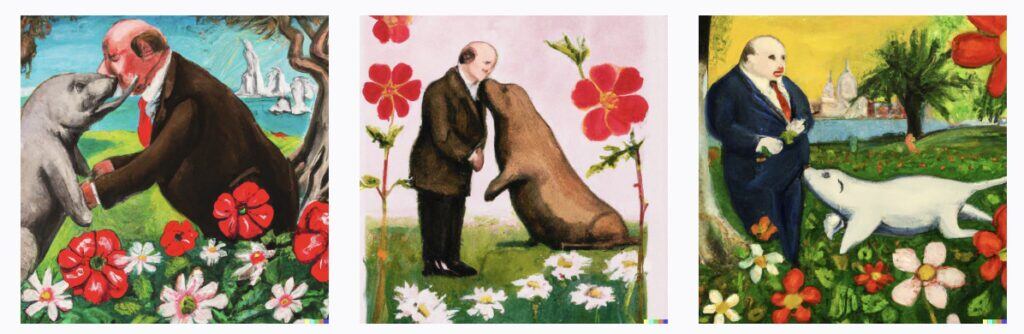

Okay, one of those might be Stalin, but still not too bad. As it turns out, I really like Lenin prompts. (Most humans are blocked by the content-filter from being depicted, for the obvious reason that the software would immediately be used to make compromising photos of celebrities, but I’ve found that Lenin and Winston Churchill somehow escape the filter.) Here are a few created in response to “a painting of Lenin marrying a manatee in a grove of flowers.”

As you can see, these men do not look too much like Lenin, but the AI does realize that Lenin is bald and wears a suit. It also knows what flowers are, and kind of what a manatee looks like, although it seems to think a manatee has legs, which also appear in response to “a painting of a manatee in an armchair smoking a hookah”:

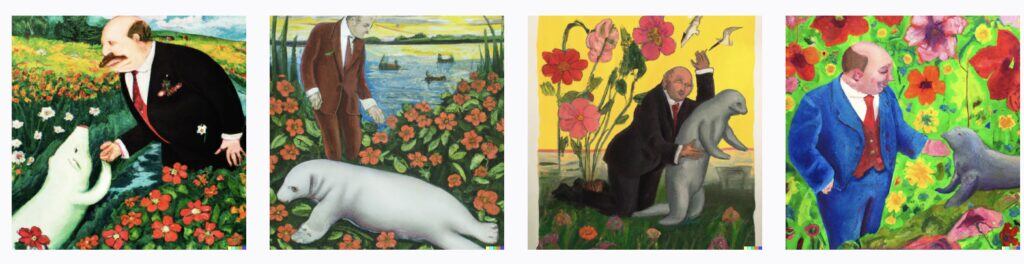

But my favorite silly prompt so far has been “a comic book cover of Winston Churchill eating a baby for dinner”:

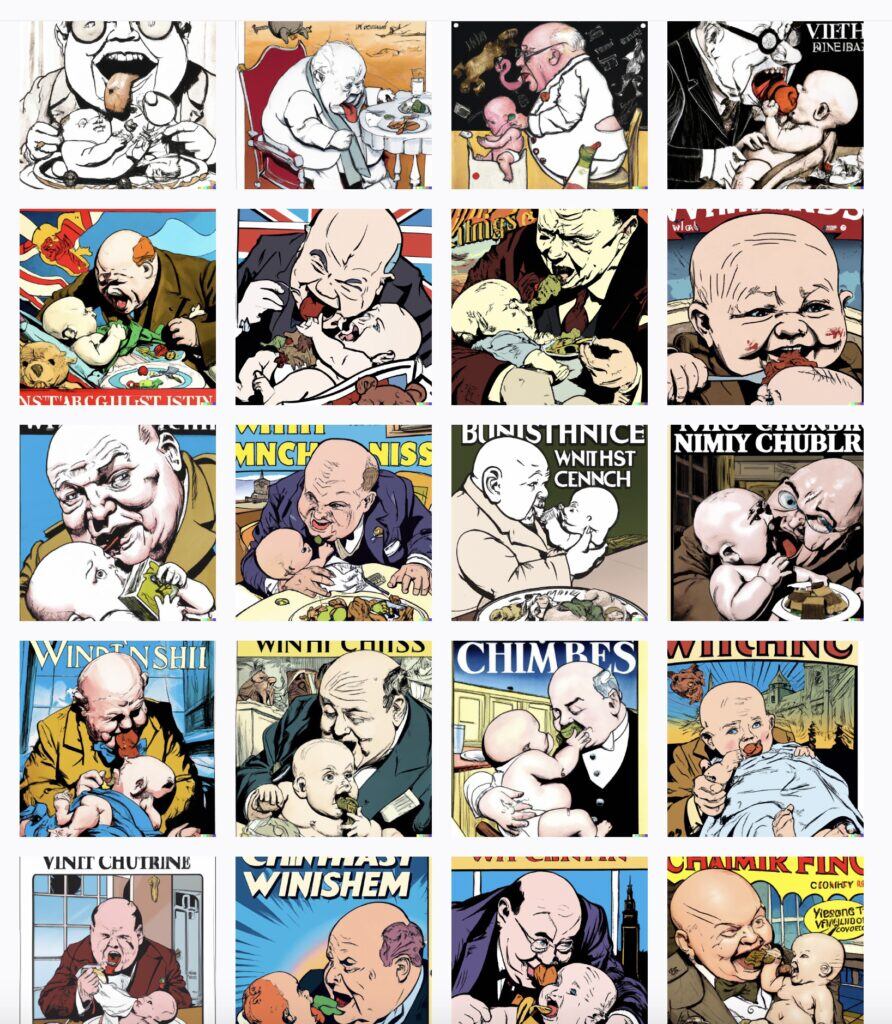

DALL-E has an extraordinary ability to mimic the styles of real artists. For instance, here I asked it to produce a Diego Rivera mural paying tribute to the work of the United States Postal Service:

I think a fair-minded person would have to conclude that this is a decent approximation of Rivera, even if a closer look reveals some slightly askew features, plus the words are in no language I understand.

Ah, but I was insatiable once I got started with this thing. Could I really have any artist from all of history paint anything I could dream of? (Or rather, an algorithmic approximation of that artist, painting its own slightly bizarre interpretation of anything I could dream of.) I decided to really go wild and get an AI painting of New Orleans, in the style of Hieronymus Bosch:

But was this really all it could do? I decided to push the limits and have DALL-E go even wilder and more Boschian. And so we have—

I think after looking closely, you will be forced to agree that this is, at the very least, quite a thing. And it’s completely generated in DALL-E. Not a single human being put pen to paper to make it.

But it’s also not entirely “AI art.” Many ideas in it are still mine, and it took a lot of work. In the upper left quadrant you will see, for instance, a group of flamingos around a fire. This is because I asked DALL-E to paint “a flock of flamingos in Hell, in the style of Bosch.” DALL-E did not decide to paint flamingos because of its own creative judgment. In manufacturing the piece, I had to go square by tiny square, telling DALL-E what to make in each section, and I was constantly erasing little bits (“hmm, that little guy’s head doesn’t look right”) and having DALL-E remake them. DALL-E was constantly generating new bits I didn’t like, and I would reject them and have DALL-E try again and offer me more variations, until there was something I did like.

So while DALL-E has technical skill far beyond anything I have—even Michelangelo would probably take a year or so to paint a picture like this—it still feels like a tool, and is “dumb” in many ways. I can’t paint like that, but I am a graphic designer, so there is some “design thought” in that image. I wouldn’t call it Art, but I think it might make a cool kitschy poster for a stoner’s dorm room. In fact, while my first reaction upon creating astonishing “paintings” was “this is the death of art,” I also felt as if tools like DALL-E could actually unlock a great deal of human creative potential. I can foresee a world not of robotic, artificial art, but highly individualized art, because the ability to turn your dreams into pictures will be in everyone’s hands. Art will be in a certain sense democratized, and people who could not previously draw or paint can unleash their creativity.

Human creativity is still required, and I haven’t felt at all like DALL-E is creative in a way that displaces human beings. I realized in creating my big Boschian panorama (which I am calling “The Garden of the Unearthly and Weird”) that I was having to use a lot of judgment to decide what should go in and what should be left out. I was the one having to decide what the thing ought to look like, and if I add up the number of judgments I had to make in the course of producing the work, I find that it’s probably somewhere in the tens of thousands.

In fact, after using these tools for a while, I suspect that many people who show off amazing pieces of work that AI has produced are pulling a kind of “magic trick” by withholding information about how many times the AI got it wrong before it got it right. When I spoke to Larson about the Lemoine/LaMDA dialogue recently, he explained how we can be tricked into thinking understanding is there when it isn’t. We’re seeing what LaMDA gets right without knowing what it might get wrong. (Google has a version of LaMDA available in its AI Test Kitchen app, but you’re highly restricted in what you can ask it. I didn’t get to inquire about the meaning of various zen koans, and I wasn’t impressed with its answers to what I did ask.) In the image-generating programs, many of the results will make no sense at all, and then one will be brilliant and perfect, but it’s clear that the program doesn’t know the difference between brilliance and crap. If it did, it would get the answers right every time, rather than getting them right in, say, 1 out of every 4 images generated.

I’ve pulled that “magic trick” a bit myself in what I’ve shown you, because I haven’t shown you all the failed prompts, or all the terrible results that I discarded. In a lot of the “Churchill eating baby” images, the baby was eating Churchill, which shows that it had no idea what I was talking about. When I tried “Lenin throwing a cat through a window,” the results were a disaster. (Lots of cats, lots of Lenins, lots of windows, and much visual chaos, but no throwing.) That’s one reason I chose to demonstrate its capabilities by making a surrealist panorama. Amusing failures are much easier to incorporate into a work that is intentionally weird and doesn’t have to make any sense. Things that a child could understand were often utterly misunderstood by a program that can appear “intelligent” when it is painting an elaborate pseudo-Picasso.

In fact, when you look closely you can see that even the impressive stuff can be quite bad. The “Diego Rivera postal workers” mural is filled with absurdities. It’s a kind of grotesque parody of a Rivera mural that doesn’t survive a second glance, except as something amusing and curious. If you look closely, you’ll see the AI hasn’t the foggiest idea how a post office works, and it’s never going to learn that by just looking at a million more pictures of post offices, even though that’s essential knowledge if you want to paint a picture of people working in one. Marcus and Davis, in Rebooting AI, and Larson in The Myth of Artificial Intelligence show that we still have no idea how to program basic common sense understanding, and as a result “intelligent” systems are bumping up against real limitations that makes them very “stupid” in a lot of ways. (Marcus and Davis suggest that if an artificially intelligent robot ever does try to come to your house and kill you, you can just confuse it by putting a putting a picture of a school bus on your front door, or painting the doorknob and the door black.)

Even as the means of creating technically impressive art improve, artists will remain in an important sense indispensable. To even try to ascend to the level of an actual Rivera mural would require an artist with a vision to modify the piece until it actually meant something—although since Rivera’s murals impress in part because he painted them, even a mural without absurdities will dazzle us less if we know it was spit out by an algorithm. (One reason great art takes our breath away is that it looks like it took someone a really long time and a lot of thought, and if we know it didn’t, we are less inclined to be impressed.) Without a human guiding it, the machine ends up churning out something purely derivative and soulless, and if my Garden of the Weird doesn’t seem completely soulless, it’s because I worked to put something of myself into it—my obsessions (flamingos, communism) and my nightmares (sky eyeballs, weird fish).

It’s still amazing how much DALL-E and Stable Diffusion can get right on the first try. But it’s also frequently clear that these programs entirely lack reasoning. Larson shows that certain kinds of reasoning we take for granted in everyday life are simply beyond the capacity of computers at the moment, which is why Siri and Alexa don’t ever seem to get much better at reasoning despite now having a colossal amount of human interaction to “learn” from. The self-driving cars are failing in part because they aren’t capable of responding to unexpected situations in the way humans can. It used to be that self-driving car proponents thought humans were bad drivers, because we have so many accidents. What the self-driving car research is showing is that humans are in fact very impressive drivers, and that we should be amazed that we have as few accidents as we do.

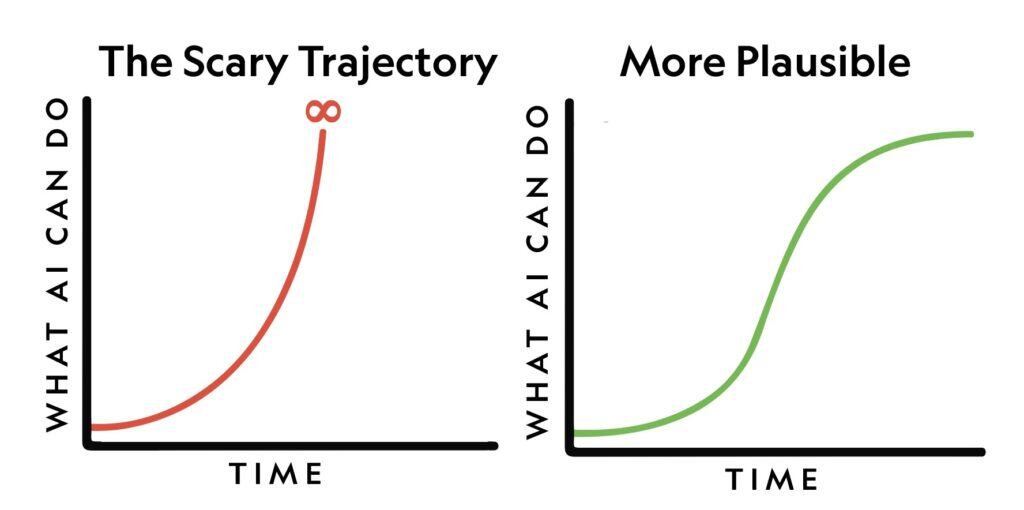

The proponents of “superintelligence” theories look at steps forward like DALL-E and see an alarming future stretching out before us. If machines become smarter and smarter on an exponential trajectory, what happens when things get out of control and head toward infinity?

Skeptics argue, however, that what looks like infinite growth might be deceptive, and the real trajectory for various technologies might looks something more like this, where an impressive spurt of development is followed by a tapering off as the technology reaches its full potential:

My own conclusion is that while there are extremely powerful applications of existing artificial intelligence (both cool and scary), we are still a very long way from even beginning to understand how to make computers that are “smarter” than ourselves, and the worries about “superintelligence” are silly and a distraction from more pressing (and plausible) problems facing humanity. Still, we don’t need to create superintelligence to create disruptive computer programs that cause global chaos. I have written before about the alarming work the military is doing in producing autonomous drone swarms that may decide on their own whether someone lives or dies. It’s partly because these weapons aren’t superintelligent that giving them a lot of control is so scary.

Less lethally, the AI art may cause a lot of problems, even if DALL-E can’t replace human creativity (and even if it never will). It’s going to get at least somewhat better, and as it gets better it’s going to threaten the jobs of artists, who are already precarious. I had a ton of fun getting it to spit out hundreds of little Boschian people, but I also felt a sense of guilt as I assembled the piece, because even though I wasn’t planning to enter the piece in an art contest or claim it as a “Nathan Robinson painting,” there was some way in which just by creating it with so much “help,” I seemed to be committing a crime against art.

I certainly don’t like where this is going, because even though I am excited by the magical ability to create stunning new images with ease, I know that we live in an economy where people have to work to survive, and automation poses a threat to people’s livelihoods. If everyone were guaranteed a decent standard of living, one could be less unsettled by the power of AI art, because the fact that a computer can do something more quickly than a human can is no reason for a human not to do it, if they are doing it for pleasure. People didn’t stop playing chess when computers began to beat people at chess. If you enjoy painting pictures of the sea, what difference does it make that a computer can paint a “better” picture of the sea? You don’t stop making recipes because Gordon Ramsay is a better chef than you are. Our pleasures are not a competition, and in an ideal world, some artists could use AI sometimes to do some things if they felt like it, just the way that they use other digital tools. (There isn’t a hard and fast line between “AI” and Photoshop.)

But the capitalist economy is competitive, and artists have to make a living. Advanced image generation programs might run into a ceiling on how much they can do, but there’s still a good chance they’ll be powerful enough to put a lot of artists out of work. Perhaps they will create new jobs for people who are uncommonly talented with image-generating softwares. (Already there are marketplaces where you can buy prompts to plug into them.) But I think it’s certainly the case that, if the programs can improve somewhat at understanding what is being asked for, a lot of design and illustration work that is today done by hand might be automated.

We should not have to worry about this. If people were guaranteed a decent standard of living, they wouldn’t need to fear the automation of their jobs. We could all “ooh” and “ahh” at DALL-E, without it being “scary.” But when people have spent years developing a skill that they now depend on to feed themselves, and look at the prospect that they will have to compete with an AI that can paint with the skills of the Great Masters, they are understandably worried. Nick Sirotich, one of the wonderful artists who contributes to this magazine, noted to me that the artist community is “already bleeding,” and foresees a world of “AI-generated content through and through, devoid of soul, purely superficial and driven only by profit.” He’s not wrong to be concerned. Would, for instance, an airport decide to commission a muralist to spend months painting a terminal wall if it could just have a free AI spit out a rough approximation that most weary travelers can’t tell from the real thing? AI isn’t predestined to destroy artists’ careers, but it might in a world ruled by the profit motive.

As a design professional who runs a magazine that is heavily dependent on human artists, I’ve been thinking about how as technology develops, we can try to use it ethically ourselves. For instance, to accompany this cover story on AI art, I made the issue cover using a combination of DALL-E, Photoshop, and InDesign.

I had to work hard on it because there were a lot of things the image generator didn’t get right (especially the frog’s hand), and I’m proud of the result. But I didn’t paint it. And it did make me think: some places are going to use these new technologies to automate jobs that were done by hand. How do we make sure Current Affairs is ethical in any use of automation? I realized, however, that automation mainly presents an ethical problem for for-profit entities, which have an institutional mandate to cut labor costs when possible. For us, a not-for-profit entity, any money that automation saves can simply be given back to the workforce. Computer assistance can actually help us boost the pay of artists, by allowing them to make things faster. If Current Affairs presently pays a designer $300 for a page and it takes them four hours to design, but then a software allows them to make the same page in ten minutes, we can still pay them $300, even if for-profit entities are trying to drive down the prices they pay. I think our responsibility as the century unfolds is not to say that we won’t embrace new technologies, but to say that we won’t ever use new technologies to cut the share of our revenue that goes to labor.

The assuring news I can offer after reading a lot about AI and playing with the latest tools is that I don’t see compelling evidence that “superintelligent computers” are possible. Some people warn that we should prepare for the arrival of superintelligence in the way those living before the invention of the atomic bomb should have thought about it. But in that case, there were good scientific reasons to think that an atomic bomb was a realistic possibility. In the case of artificial intelligence, we don’t know how to make machines think. This may have something to do with the fact that, ultimately, they are not alive, and intelligence is a property of biological life forms. Those who hype AI risk tend to believe that the human mind is just a kind of elaborate computer program, and that it doesn’t matter that we’re made of flesh and bone and computers aren’t, because if the mind is a “program” then you could “simulate” it on a sufficiently advanced machine. But I suspect that as the limitations of our capacity to improve the intelligence of computers become clear, that position may be reconsidered.

The bad news is that, as Larson points out, our technology doesn’t need to be very smart in order to hurt us. Nuclear weapons aren’t intelligent, but a miscalculation with them could wipe out most of the species. Smartphone addiction doesn’t require our phones to be sentient life forms that can reason on our level, it just requires them to be sufficiently advanced to hook us. AI art can keep getting things hilariously wrong and still put a lot of creative professionals out of work. In a world where everyone knew they could be comfortable and secure, technological advancements wouldn’t have to terrify us so much. But we don’t yet live in such a world.

You can see more of my weird AI art on a special Instagram account I’ve set up for it called Esoteric Artifice. You can also buy my “Cat Karl Marx,” “Hieronymus Bosch New Orleans,” and “Garden of the Unearthly and Weird” as Etsy products, because enough people have asked me to print them on things to where I feel obligated to satisfy public demand.