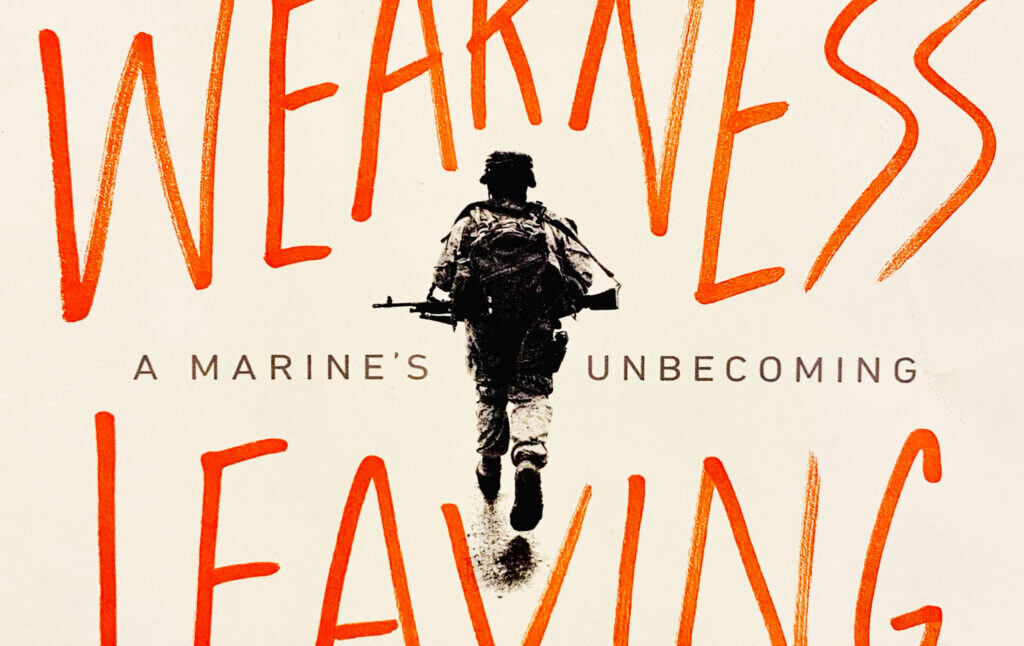

Being a Man in the Marines

To be a man in the Marines, as Lyle Jeremy Rubin explains in his memoir, was to be a person not so much in search of freedom or democracy but one’s own manhood.

In thinking about why I signed up and shipped off, I’ve been forced to question the motives of the nation and world that helped make me, to come to terms with living pasts of empire and masculine excess, and to consider how these histories reproduce one another from one place to another, and from one time to the next.

I suppose my initial failures in the Corps first jolted me into asking such questions, but painful moments as a child and young adult had already set the conditions for the questioning. Some of these moments involved the mundane aggressions of my father. Others, the more exceptional predations of my friend Adam’s older brother.

To be a man in the Marines was to be like my father or Adam’s brother. It was to channel life’s difficulties into rage, store one’s rage like a battery stores energy, and then apply such rage to whatever battle must be won. It was also to fail to contain that rage, like a corroded battery leaks acid.

But to be a man in the Marines was also more than that. There was a naturalization of the boyish violence I got to know as a child, a violence that conditioned everyone involved, from the perpetrator to the victim to the witness, to become not only accustomed to its blunt impact but also maybe even to welcome it. And it was a special kind of violence that doubled as something sexual.

Reimagining that violence in recent years has meant placing it in its proper contexts. It has meant seeing it as of a piece with my decision to become a marine and recognizing how it played out in ways subtle and explicit once I did.

I often drift back to the collective humiliation, when we were all, the whole platoon, at our most exposed, at our most naked, literally. I think back to our headlong discarding of tops, trousers, and briefs in between our racks. I recall the tripping and wobbling as we barreled to the head all at once—its entryway halfway down the narrow building on the starboard side—to take our shits and pisses or scrub our bodies under the high-pressure showers. We had only five minutes to conduct the aforementioned, so we sprinted and elbowed as if future generations depended on it.

We were always aware of one another’s bodies, bodies knocking into one another, moving in sync. Our sprints were expertly orchestrated, lest we slip on the wet deck. Our elbowing was subtle, just about invisible, lest we risk needless frictions or full-blown tussles with those we relied on. Our pisses were well-aimed and efficient, lest we frustrate the man to our immediate left or right at the trough urinal or the dozen men queued up behind us bursting to let one out before deadline.

Insecurities were everywhere.

I saw star lacrosse players bite their lower lips in humiliation after nicking themselves during a speed shave. I saw them jerk in all directions to make sure no one saw what I saw and dab the slit with toilet paper or resolve to let it dry in a manner least conducive to judgment. I saw former shortstops assess their own pecs as they stood next to the more developed pecs of others. Then I saw them scour their breasts with a bar of soap in a self-conscious fit, as if peeking was a mere preparatory step to chest cleaning. I saw everyone sweat trying not to be caught stealing glimpses at other cocks, and I saw the childlike mortification of everyone involved when someone was.

The five weeks I spent disintegrating at OCS (Officer Candidates School) amounts to a haze. I was too beaten down to make much of it. But the one element that has always stayed with me, like a gelatinous burn, is the feeling of having been placed in an enclosed environment with men who were, despite their current attainments and skill sets, not all that different from my father or from me and Adam. That is to say, men who had once been made to feel weak or inadequate; men who, like most, were now figuring out roles passed down to them by patriarchs, whether from real life or from the big or small screen; men obsessed with protecting and enriching themselves and those they cherished; men who collected taxing experiences and challenges as if they were armor for battles ahead; men in the ultimate instance concerned with preserving and combining their gains, ordering and controlling anything or anyone on the outside who might get in their way; men by gradations and in various phases not so much in search of freedom and democracy as of their own manhood.

Over a half century ago, during the peak of the United States’ war in Vietnam, a first lieutenant by the name of William J. Quigley was ordered to build a marsh-like training circuit at officer school where, upon completion, “each candidate should look like they tangled with two constipated pit bulls, and lost.”

The lieutenant was a mustang, a prior gunnery sergeant who had served numerous tours in Korea and Vietnam before transitioning to the commissioned officer brass, or, as enlisted folks sometimes put it, the dark side. The good lieutenant, who ascended to the rank of lieutenant colonel before his retirement, never exhibited any signs of relapse to his lawless mustang ways. But the circuit he created, called “the Quigley” since its inception, bears the marks of lawlessness.

The circuit often hosts future executives and bankers from the business programs of schools like Johns Hopkins, Penn State, and The Wharton School, in what Wharton sells as a two-day “military simulation leadership venture.” Its chief participants, however, are officer candidates looking to master a range of combat contingencies, from an ambush to a frontal assault, where mock fire or grenade eruptions determine the mandated formation. Along the way, each team negotiates hypothetically mine-triggered log barriers while maintaining concealed profiles. They low crawl in bog under barbed-wire obstacles and straddle ropes in tactical chicken-wing contortions. Before and after running Quigley’s gauntlet, candidates pass through wooded terrain in various squad and fire team formations with names like “the column,” “the wedge,” “the left echelon,” or “the right skirmishers.”

The Quigley more specifically refers to the swamp portion, where everyone slithers in the muck with their rifles held above the turbid waters. If it’s winter, you are greeted with ice. If summer, snakes. A body-length culvert, overflowing with the bowels of the swamp, signals the climax. Candidates have to dunk through on their backs, weapons still held high, advancing far enough out the other side so that they can breathe again. If a body doesn’t appear after an allotted number of seconds, an instructor standing above the culvert dips under to fetch it.

On the morning I did the Quigley, I was trending hypothermic by the time I reached the finish line. Within seconds, as my team and I turned toward the steaming showers about fifteen minutes out, a pack of sergeant instructors swarmed me. I was ordered to the mud-caked ground to conduct an indefinite series of push-ups. Their gibes were standard issue, though some were particular to my type. “You’re so smart you’re stupid, Rubin!” which, in my diminished condition, I received as a mild compliment. Then there was the cryptic: “Someone lied to you, Rubin!”—although the implication was clear enough, and it stung—and the ominous: “You’re gonna get someone killed, Rubin!” or “Something’s gonna happen to you, Rubin!” Even today I wonder whether there was wisdom in those warnings, especially considered alongside the perennial favorite: “You’re weak, Rubin, you’re weak!”

The greater part of the pain they inflicted that day, in any case, proved more immediate. Beyond the cold, I was exhausted, already existing on just two to three hours of sleep a night—if that. I made it to three or four push-ups before collapsing into the puddle of gunk.

For the first and last time in my adult life, I mewled in the open. Heads swiveled in my direction while seconds that felt like an age passed. But when my torturers resumed their invective, the onlookers went on their way. The hats had done what they set out to do, and I was dismissed to the showers shortly afterward.

The sense of their triumph stuck with me. But I felt a sense of relief ripple among my classmates, too, all of whom were thankful it wasn’t them facedown in the sludge.

In the military, the weakest link receives both hatred and appreciation. They are hated because, on an hour-to-hour basis, they can make the workday more exasperating. If they’re not reined in, they can even get someone hurt. Appreciation, on the other hand, stems from their hanging on to the lowest rung of the ladder, thus freeing others from occupying that position. Even the penultimate outcast could enjoy a sense of reprieve, because the person below would be scapegoated round the clock.

None of this departs much from the social norm, although the military does offer a heightened version. I had found myself last before, specifically as a strong-armed youngster, but I had been too young then to evaluate the logic of such a game. By finding myself last again almost a decade later, I was given another opportunity to see the problem. And once I began to see it, I never stopped.

During the first week of OCS, I commiserated with a candidate who had likewise been targeted for his bookworm habits. A fellow New Englander with Bobby Kennedy’s grin, he’d run the fastest three-mile in the company. That, combined with his Ivy League pedigree, indicated advanced competence. I assumed I’d be the first to get drummed out of the program.

Each of us was slight, but whereas he looked like a hormone-supplemented stalk of hay, my body was more suburban, more in between. I’ll never know what specific texts convinced my Dartmouth-educated counterpart to become a marine, but I suspect they were less wonky and more literary than mine. He was an English major steeped in the predictable canon, from Homer to Joyce. Probably, like me, he’d read the First World War poets wrong.

It turned out I would make it to the fifth week without volunteering my exit, whereas he hit the evacuation button sometime before the second. Maybe he was wiser.

The weeks that followed his departure brought further sleeplessness, horrendous paranoia and hallucinations, cerebral and bodily decay, and a platoon that had been made—partly by instructors who never let my smallest error pass without communal recognition—to despise me. Dartmouth had been the only person with whom I was able to pass a friendly word or two, and when he left, I was all alone.

Almost a month later, however, on the verge of my own exit, I did get to establish one other fleeting friendship. Reilly, another candidate, was all biceps and triceps, a college wrestler from a state school. He might have been prior enlisted, too. It was a frigid early morning around 6, and the rising sun blasted the intense and foreboding red of Magritte’s “The Banquet.” In the actual chow line, every candidate’s sidestep from one menu requirement to the next was choreographed with mathematical rigor.

As the first to eat, Reilly and I were the first to be stationed outside the dining facility, holding down our platoon’s turf before everyone would be called to attention for the post-chow formation. Most of the candidates were still inside the hall, so Reilly and I were free to talk for a few minutes.

We were fixating on the sun’s dazzling imprints on the Potomac when he mentioned in passing the urban legends about despairing candidates who had tried to swim across the river in last-ditch breakaway attempts. Maybe not during the winter, he granted. But maybe so. I said something to the effect that “I guess I empathize with those sons of bitches, whether they existed or not.”

He asked me how I was feeling. I told him not so well. He patted me on the back, a gesture as familiar as though we’d known each other since birth. “And why’s that, buddy?” he asked, looking me directly in the eyes.

I told him he probably already knew the answer to that question. I’d likely be chopped at the fifth-week boards, and I was losing all faith in my ability to redeem myself. He told me not to give up, to keep persisting no matter how wretched it got or how much the other guys abhorred me. It wasn’t me they abhorred anyway, but the part I was playing, and it was, as I myself had noticed, an abhorrence mixed with gratitude. The sun was almost all the way up, and most of the platoon was headed our way for the next formation.

At the end, when it was clear I would be leaving OCS, Reilly volunteered to see me out. He helped pack my gear at my rack, encouraging me to give it another go when I could. In the empty squad bay, while everyone else was off on a physical training exercise, he confided that he’d faced similar challenges, just as mortifying as those I’d endured. It turned out Reilly had flunked out of a military course, too. It had taken him years to tell anyone about it.

With the mask of self-command he’d worn placed to one side, a more flawed human underneath was revealed. As he told the story of his defeat, his pointer finger brushed under his eye. I now realize that, while he taught me the most effective way to fold and pack my wardrobe into a duffel bag, he wanted me to see him as something other than a coldhearted contender. Just as I wanted to be seen as something other than a fiasco.

Had I succeeded at OCS, it is improbable such circumstances would ever have arisen between the two of us. But that day, they did. When he suggested my own failures would give rise to strength, it was not the strength of force he referred to. It was a deeper power.

It’s shocking, the parts of ourselves we bury to become marines. Or the parts we hope to bury by becoming marines. Or the parts we find ourselves burying well after we’ve left the Marines. I’m still rediscovering those buried parts.

It’s not that the Corps fertilizes those buried selves and allows them to grow into an organic whole. The human psyche is too stubborn and complex to take up such a contract. It’s that such a revered institution draws from a pool of men aching to sacrifice their weaknesses on an altar of conventional masculinity.

The endeavor which I learned as a marine is defined by a tragic tension: in lieu of the universal tenderness required of a true community, a brotherhood, each of us marines craved codes of masculinity—a virile individualism coupled with a self-denying solidarity. At the level of the person, the strain of this tension culminates, to an overwhelming measure, in misery or death. Raised to the level of a nation, especially a nation endlessly driven to expand its influence and power, it culminates in much more of the same.

This incongruity pervades America: in the corporate workplace, where laborers are expected to work together as a team while vying with one another to get ahead or even just to stay afloat; in rural or exurban towns, where communal esprit de corps goes hand in hand with little bourgeois fiefdoms or small business tyrannies; in cities, where infinite (and often bizarre) attempts to revive some approximation of trusting camaraderie coexist with an ever-intensifying anomie; in politics, where genuine efforts to forge religious, patriotic, or socialist bonds are poisoned by grifters, demagogues, and anyone else looking to make a buck or build a brand. Much of this can’t be avoided. As the smart set has become accustomed to saying, it’s the human predicament.

Freud provided the proof in Civilization and Its Discontents, published in 1930. He was reacting to the First World War while seemingly anticipating the Second. For all his blind spots and errors, he understood what happens when the strain between individualist and collectivist instincts goes untreated:

“If the evolution of civilization has such a far-reaching similarity with the development of an individual, and if the same methods are employed in both, would not the diagnosis be justified that many systems of civilization … have become neurotic under the pressure of the civilizing trends? … The fateful question of the human species seems to me to be whether and to what extent the cultural process developed in it will succeed in mastering the derangements of communal life caused by the human instinct of aggression and self-destruction.“

The United States remains one of the most undertreated civilizations in modern times, suffering the highest suicide rate and lowest life expectancy among many of its high-income peers, despite the highest spending on health care. It has one of the highest poverty rates in the developed world despite being the richest nation. For a long while now, it has outranked other wealthy countries in homicide rate despite having one of the highest numbers of police officers—and despite those police being highly militarized. And despite repeated cycles of moral reckoning and attempts at police reform, the United States, according to the Council on Foreign Relations, “far surpasses most wealthy democracies in killings by police.”

Many strategies could doubtless reverse these trends, even dramatically so. Universal healthcare, a revived labor movement, aggressive gun regulations and buybacks, abolishing the qualified immunity that protects cops from accountability, and redirection from carceral to social investments, for starters. But at some point Americans must ask themselves: Why has the country most successful at accumulating private wealth and power, in large part through the unmatched imposition of public violence at home and abroad, also proved one of the least successful at dispensing a baseline quality of life for its residents? What are the relationships among capitalist individualism, imperialist solidarity, and so much despair? And what are we as Americans prepared to do about it, beyond the usual fig leaf of symbolic action or patchwork refinements?

To move beyond the provisional fix requires facing these difficulties as integral parts of cultures and systems rather than as discrete problems to be solved. There is a reason, after all, that the bipartisan congressional coalition most dedicated to maintaining the basic extant organization of a historically unequal society calls itself the “Problem Solvers Caucus.”

This also entails understanding how behaviors interact with one another, and how extremes interact with norms. We may know that around 1 in 3 people experience rape, sexual or physical violence, or stalking in their lives, as of the most recent data. Or that every nine minutes Child Protective Services confirms or finds strong evidence for a child abuse claim, per the U.S. Department of Health. Or that, according to a 2009 study, sexual assault victimization rates among high school peers were 26 percent for boys and 51 percent for girls. But statistics can never tell the whole story.

The gaps, especially the framing gaps, the lacunae that throw everything else into stark relief, can only be filled by art, literature, and other less quantitative means of communication. The fact that my father never beat me, my brothers, or my mom makes me, in some people’s eyes, unqualified to speak about what he did do. The fact that I was not molested by adults but rather ensnared in everyday “boys will be boys” mischief renders me uninteresting to others. And these laws of intrigue or compassion don’t just pertain to the patriarchal mainstream. They are found in inverted forms as well, including among those who loathe the patriarchy but who still feel a need to give each hardship a grade.

If these strictures did nothing more than discourage people from talking about their lives, it would be troubling, but not catastrophic. But what they also do, and are intended to do, is ensure an inertial discourse on violence that is resistant to investigating the vast continuities in which injustice develops, festers, and spreads.

My story is similar to others I’ve heard or overheard, particularly from disgruntled marines, however much it differs in intensity. When I gave my initial go at OCS, the outcome was not a commission but instead the smashing of both my person and my worldview into a thousand irreparable pieces; the unexamined life of my youth came to a close. It was then, by force of circumstance, that I began a process of interrogation—of myself and my nation. And it was then that I perceived the saga of pain-fueled masculinity, my own and others’, and how this masculinity is cycled through a series of contests, as if we all were taking part in a unifying, lifelong tournament of pain.