The War on Palestine

Historian Rashid Khalidi explains why the Israel-Palestine conflict is best understood as a war on Palestine.

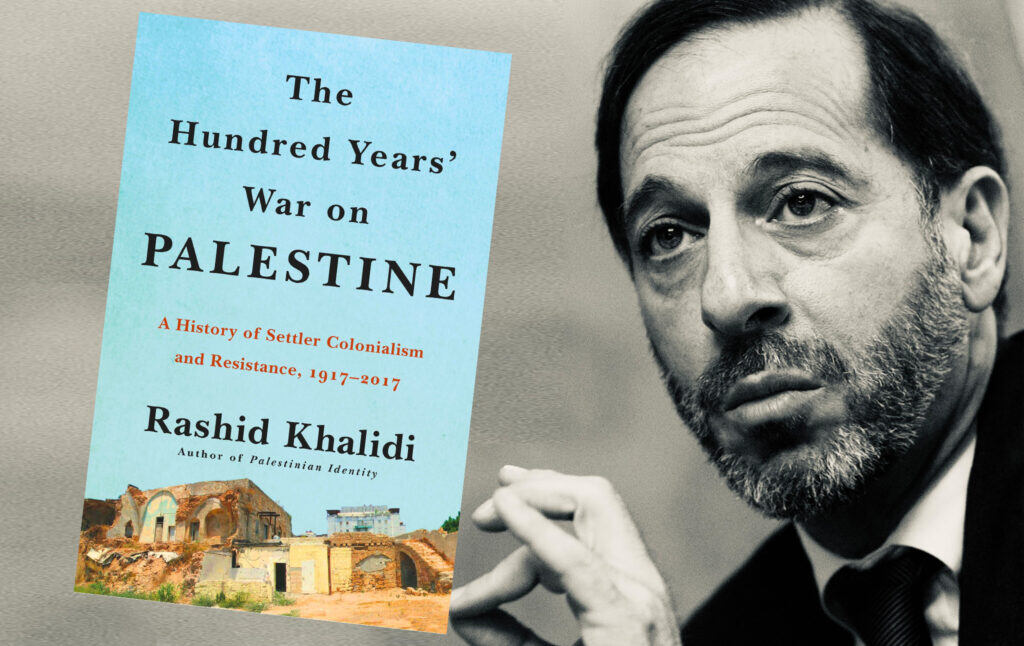

Today, we see children killed in Gaza by Israeli airstrikes, but anyone who gets their understanding of the Israel-Palestine conflict from news reports lacks the context necessary to make sense of the horrors they are seeing. To understand why there is an Israel-Palestine conflict today, we have to go back 100 years to see what Palestine was like before the state of Israel was established and how things have changed since. To discuss the background of the conflict, Current Affairs editor-in-chief Nathan J. Robinson recently spoke to one of the leading historians on the region, Rashid Khalidi of Columbia University. He is the author of The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017, edits the Journal of Palestine Studies, and in the ‘90s served as an advisor to the Palestinian delegation to the Madrid and Washington Arab-Israeli peace negotiations. This interview has been edited for grammar and clarity.

Robinson

Something that comes across in The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine is that in order to understand what is going on in Palestine today, to make sense of the events we see unfolding, we really have to go back 100 years. So let’s start with Palestine at the turn of the 20th century, as you do in the book. Paint a picture of Palestine at the beginning, pre-Zionism.

Khalidi

You’re right to say let’s start with the history. We’re often told to forget the history. Well, they want us to forget the history because without it, you can’t understand what’s going on now, and they can put all kinds of silly ideas into our heads—”making deserts bloom,” “only democracy in the Middle East,” and that sort of nonsense.

The history is simple, actually. People always say, “Oh, it’s very complex.” It’s not complex at all. This was a society made up of Muslims, Christians, and Jews, who identified in different ways but whose lingua franca was Arabic and whose governmental language was, under the Ottomans, Turkish. It was a society in rapid development. Education was developing rapidly, even though the literacy rate was still not very high. Roads, railways, electrification, and so on were just developing at the turn of the century.

And it was a society that had been and was relatively peaceful for a very, very long period of time. There is not a history of violence in Palestine between Muslims and Jews or Muslims and Christians, or in fact any of the various groups in Palestine at the time, nor had there been for several hundreds of years.

So this was a developing society, backwards in many ways, largely rural, with an upper class that monopolized power, and was well connected to the Ottoman ruling authorities. But one that, as I say, was actually developing rather rapidly.

Robinson

You say that it was a society of Muslims, Christians, and Jews, but the demographics were not equal.

Khalidi

Right before, during, and after World War I, when we have relatively good statistics, the Jewish population of Palestine was in the realm of around 6 percent, maybe 8 percent. There was a larger proportion of Christians, and the overwhelming majority of people were Muslims. Almost all of that population—certainly Muslim and Christian, but also a large part of the Jewish population—were Arabic speaking. The Jewish population spoke several other languages; some were immigrants and spoke their languages of origin. Many were beginning to speak Hebrew; most of them used Hebrew as a sacred language. But the lingua franca for most of the existing population in Palestine was Arabic. And many of them felt themselves part of that society, even though they were distinct in religious terms.

This, of course, is before the rise of modern political Zionism. We’re talking about the indigenous Jewish population of Palestine at the time. Immigrants were arriving, but they were still a minority. And these immigrants were people who were motivated by political ideas, mainly Zionism.

Robinson

Well, I want to get to the effect of Zionism on Palestine in the early 20th century. In the book, you quote from an extraordinary letter written by your great-great uncle, who was the mayor of Jerusalem. He wrote to Theodor Herzl, the founder of Zionism, and said, in effect: your people have a historical association with this land, but Zionism is going to lead to a disaster for Palestine. This prophetic letter is a kind of warning.

Khalidi

He was an interesting character. His name was Yusuf Dia Pasha al-Khalidi. He had been, as you say, mayor of Jerusalem. He was also the elected deputy for Jerusalem in the 1878 Ottoman Parliament. And he was an educated man. He had studied and taught in Europe, he taught in Vienna at the Royal Imperial University. He spoke Arabic, English, and French. And he was fully aware of what political Zionism entailed. It entailed turning an Arab country into a Jewish state. That was the title of Herzl’s famous monograph, Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State, or The State of the Jews, depending on how you choose to translate it). He knew about those writings. He knew about the first Zionist Congress in 1897.

So when he writes to Herzl in 1898, he’s fully aware of what political Zionism entails. It’s not just a historic connection of the Jewish people to the land of Israel, which he talks about in the letter and admits and celebrates. But it is rather a replacement of the existing population with a new population. And he says Zionism in and of itself is fine. But you can’t do it here. There are people here that will not be supplanted. And so, as you say, I think the letter is prophetic, and I choose to open the book with that letter. And then with Herzl’s response.

Robinson

Herzl doesn’t heed the warning, needless to say.

Khalidi

Well, he does what Zionist leaders have done ever since. He acts as if the Arabs are irrelevant, or are fools, and he essentially blows Yusuf al-Khalidi off. He just tells him, Oh, have no fear, everything’s fine. And he says something rather interesting. At no stage in his letter did Yusuf al-Khalidi talk about the displacement or the replacement or the elimination of the Palestinians. He said: You can’t do this here because there’s an existing people. And in his letter, strangely, Herzl says, there’s no idea of replacing these people. Then you go back to Herzl’s diary, and in fact, he is thinking about spiriting the population across the frontier. So it’s an unasked question, which Herzl answers, which I think is very revelatory.

Robinson

So your great-great uncle gets the reply and thinks Hmm, I didn’t ask you about replacement. It is fascinating that when you go back to a lot of the early Zionist discourse, in the romantic imagination, Palestine is a desolate desert that can be colonized with no problems. But a lot of the early Zionists admit pretty much openly: Look, we’re trying to colonize a country that has people in it; we need to have a discussion on how to get rid of them.

Khalidi

There are two sets of Zionists insofar as how they regard the Arabs. There are those who, as you say, are blunt about it. People like Ze’ev Jabotinsky, who was the leader of the revisionist strain of Zionism, which has pretty much dominated Israeli politics since 1977—every prime minister, with one or two exceptions, since 1977 was a follower of Jabotinsky. He was very blunt about it. He says: Yes, we’re going to replace these people. And we need an iron wall—meaning of the British—to help us to do this. And we are colonizing and all colonizers face resistance, every people resists colonization. So Jabotinsky is very blunt about it. [ Jabotinsky wrote: “Zionist colonisation must either stop, or else proceed regardless of the native population. Which means that it can proceed and develop only under the protection of a power that is independent of the native population—behind an iron wall, which the native population cannot breach.”]

Many other Zionist leaders, I think, were either deceptive or were deceiving themselves in pretending that somehow this could be arranged without eliminating the existing population one way or another—removing, driving them out, whatever. And that was crucial to their propaganda abroad. Because if they said, “We’re gonna go in there, and we’re gonna face enormous resistance, and these people will fight like hell to retain their country and they have national aspirations,” it would have been a little harder to raise money and engender support for the Zionist project.

So people like Jabotinsky, who are in the minority, were pushed to the sidelines by the leaders of the mainstream Zionist movement, for whom it was really important to sell this to British and American statesmen, European statesmen, and to the Jewish communities the world over as a project that could be done without violence, without replacing an existing people. Or by saying they’re not a “real” people, they’re just Bedouins or they have no roots here, or by ignoring their existence. A land without a people for a people without a land was a slogan that many Zionist leaders repeated. Israel Zangwill is the most noted. Of course, there were people on the land, like Jabotinsky admitted.

Robinson

Now, just to clarify, the reason that you’re saying that the original political Zionist project couldn’t have been done without expulsion or ethnic cleansing, is because imposing a Jewish state necessitated it? Can you describe what it was about the plan that made violence unavoidable?

Khalidi

It’s actually very simple. You have an overwhelming Arab majority. So you either drive them out or you flood them with new immigrants, so that you have a Jewish majority. And so you completely transform the nature of the country, either by massive immigration, which creates a new Jewish majority (and then you have an Arab minority in a Jewish majority state), or by driving as many as possible of the existing population out.

The objective of Zionists was not to live as a Jewish minority in Palestine. The Arabs are a majority in Palestine. Right up to 1948, 65 percent of the population of the country was Arab. In 1948, the year after the United Nations gave most of the country to a 35, or 33 percent, Jewish minority, you would have to either have had, as I’ve said, massive immigration, which never really fully developed, or you had to plan to get rid of them. Those are the only two ways you could create a Jewish majority state. And the objective was for Jews to leave a situation in which they were a minority in Europe, and to create a new Jewish majority political entity, a Jewish state. And so Herzl lays it out in 1897. And that is the objective of Zionism to this day.

Robinson

When you go to the writings of, for instance, David Ben-Gurion, at the point at which it’s been concluded that immigration alone will not create a Jewish majority, you find pretty open acknowledgment that what is needed is what is euphemistically called transfer. We’re going to have to transfer some people. I don’t know how you can describe that other than as ethnic cleansing.

Khalidi

There’s no other way to describe it but as ethnic cleansing. “Transfer” was an Orwellian euphemism, which Zionism appropriated and used throughout. The idea was that people weren’t being uprooted and forced to leave, they were simply being “transferred” from place to place. It was a nice, neat, clean way of saying “kicking these people out of their homes and stealing their property,” which is actually what happened.

Robinson

And this helps us to understand the development of Palestinian resistance to this project. Today, this is characterized often as being based on irrational anti-Semitism. But as you point out, when we understand the history of the development of this resistance, we see it differently. There are even early Zionists on the record saying things like I don’t know how you expect the Palestinians to react, they’re going to react the same way every indigenous population reacts when there is a colonial project to impose minority rule. [Ben-Gurion himself said: “If I were an Arab leader, I would never sign an agreement with Israel. It is normal; we have taken their country.”]

Khalidi

I mean, it’s as absurd to call the Palestinian resistance to having their country taken away, being expelled and having their property stolen, “anti-Semitism” as to describe Algerian resistance to the French as anti-France-ism, or South African resistance to the Boers as anti-Boerism, or Native American resistance as anti-American. This is anti-colonial resistance by an indigenous people in peril of losing their homeland, their property, and in many cases, their lives. It has nothing to do with anti-Semitism. That’s one of the most vicious canards around. To claim that any form of resistance to colonialism, wherever it may be, is motivated by some kind of racist etiology is absurd. I mean, the Irish were not anti-British; the Irish are simply opposed to British English colonialism. Same with other colonized peoples.

Robinson

I’m dwelling here on what I think is one of the most important takeaways from your book, which is that the development of the modern state of Israel—which is a recent development, founded within the lifetimes of people who are still alive today—is a colonial project. It’s also backed crucially by the British and wouldn’t have come into being without the British Empire.

Khalidi

Zionism is a unique colonial project. It’s easy to say “this is a form of colonialism” or settler colonialism, which it was. It self-described as colonial. Early Zionists were not ashamed to use the word colonial or colonialism. The Jewish Colonization Agency was one of the main financing arms of the settlement project. So that’s incontrovertible.

It was also, however, a national project. It was not an emanation of a mother country, the way that English settlers in North America or in Australia were or French settlers in Algeria were. It was a separate independent national project, which without the backing of great European colonial powers would never have been able to succeed. It operated in terms of settler colonialism, but had a national aspect to it. And it’s very important to understand that it has been very different in that respect from South Africa or Nigeria, or North America or Australia or Kenya, or other settler colonial projects.

Robinson

One of the charges that is brought up often is that while Jewish settlers in Palestine were trying to establish a nation-state, the Palestinians supposedly did not constitute a nation, and therefore were not entitled to a state. Golda Meir infamously said: “There was no such thing as Palestinians. … It was not as though there was a Palestinian people in Palestine considering itself as a Palestinian people and we came and threw them out and took their country from them. They did not exist.” The idea was that while Palestinians may have existed as individual people, they did not have a sufficiently well-developed collective identity to be entitled to self-determination. How did Palestinian identity develop over time and how do you think about its relevance?

Khalidi

That’s an important question, because most modern national identities in the overwhelming majority of countries in the world are, like both Palestinian and Israeli identity, extremely recent. The great-great-grandparents of every Israeli never thought of themselves as Israelis. There was no Israel, there was no idea of a nation-state encompassing all Jews, which is what Zionism involves, in 1800. Nobody thought of that. It’s a recent modern national identity, as is Palestinian, as is Arab.

All of these have roots in earlier forms of identity. So there’s a Jewish idea of peoplehood. There’s an Arab idea of peoplehood. There are linguistic bonds and religious elements that come into modern nationalism. But modern nation-state nationalism is a very, very recent phenomenon. I am right now in France. The part of France I am in was not part of the French monarchy until the 15th century. They spoke a different language. I believe it’s Montesquieu, or one of the great French philosophes who said, these people are savages. They don’t speak French. They spoke Provençal. The unification of France is a French revolutionary and 19th century project. And the creation of “Frenchmen” out of peasants is a result of education and the army.

So modern national identities have roots that go back, whether we’re talking about Israeli or Palestinian or Arab or whatever, but they are all relatively recent, i.e., the last couple of centuries, in almost every case. Of course, one of the great successes of Zionism is to hitch modern political Zionism, a 120-year-old phenomenon, to the biblical narrative and to Jewish peoplehood. The Palestinians do the same thing, the Philistines, the Canaanites, the Jebusites, and so on and so forth. This is the way in which modern identities are constructed. Modern identities are transformed from either being religious into modern nation-state nationalisms. And so this is what happens with the Palestinians. It has to be understood, however, that the blows that the Palestinians received, the Great Revolt that they launched against the British in the 1930s, the expulsion of the majority of Palestinians from the country in 1948, helped to mold and shape an identity that was already developing. As is often the case, conflict and trauma often shape and change identities on a mass basis. It’s also true for individuals.

Robinson

So it may be true that the contemporary nation of Palestine, the “imagined community,” has been formed in part through resistance to the project of taking away the country. But it is also true that, as you say, every national identity is a recent construct. And if we apply the same standards as Meir did to Palestinians, “there were no Israelis” either. After all, nearly every Israeli leader changed their surname as part of the project. [Golda Meir was born Golda Mabovitch, Shimon Peres was born Szymon Perski, David Ben-Gurion was born David Grün, Ariel Sharon was born Ariel Scheinermann, etc.] Then there was the changing of all the existing names in Palestine, giving everything a Hebrew name.

Khalidi

You can say two things about this. First, the construction of identities and imagined communities is universal. If you were to apply the same standards, there would be no Lebanese, no Iraqi, no Turkish, and so on, identity, which is not to say there were not states there before, but the Ottoman State was not a Turkish state, the Qajar state was not an Iranian state, even the Egyptian state, which goes back to Pharaonic times, had all kinds of different forms of identity. So the reconstruction and the manipulation, if you want, of preexisting identities, is universal.

The other thing to say is that in this case, what you see is a project of renaming and taking over, which is unique to settler colonial projects. I live in New York on an island called Manhattan, which happens to have a Native American name. But I live in a state called New York named for the Duke of York. That’s what settler colonial projects do. All of Australia, all of New Zealand, all of Canada, all of the United States, and all of Israel has named certain places and rivers and mountains and so on, some of which reflect the original naming, but most of which are imposed in a new language and reflecting a new culture, the culture of the colonizers.

Robinson

A common story about the founding of the State of Israel is that in 1947 the Palestinians were offered a state and declined it, thus creating their own problem. Perhaps you could respond to this particular pernicious myth.

Khalidi

Palestinians always relied on the terms of the Mandate for Palestine that was given to Britain by the League of Nations, which said that the mandatory power was supposed to work toward self-determination. There was no self-determination of Palestine at any time, between the British conquest of the country in 1917 and the handover of the problem to the UN in 1947. Self-determination would have entailed a Palestinian Arab majority state. That was self-determination. Every other state under mandate received such independence. Only Palestine was exempted from what one of the articles of the covenant of the League of Nations said was the whole purpose of the mandate system.

So the Palestinians said, “We were supposed to become independent. We’re the majority. We should have a country of our own.” If there’s a Jewish minority, fine. It was only 35 percent in 1948, by the way, even after waves of immigration. And the United Nations simply ignored its own charter, which talks about self-determination. Self-determination would have meant the majority ruling or getting the majority of the country. Instead, the United Nations, under the impetus of the United States and the Soviet Union, which wanted the creation of a Jewish state, basically divided the country up, giving the one-third of the population, a minority, more than half the country including most of the arable land.

It’s inconceivable that any people would have accepted giving up more than 55 percent of their country to a minority. Imagine if someone came along and tried to establish a new state in the United States and said “we’re going to take 55 percent of it.” Most Americans would probably not go along with that, and most Palestinians did not go along with the partition.

Robinson

It’s also true that many of the Zionist leaders had made it fairly clear that they intended to use this as a stepping stone. Partition was accepted as what was being offered at the moment, but not as an end to the project of building a Jewish state in Palestine.

Khalidi

No, and the various military plans that the Zionist militias laid out in the months before partition came into effect in 1948 were dedicated to taking over areas that were actually allocated to the Arab state under partition, such as the city of Jaffa or areas along the road to Jerusalem. So expansion for strategic reasons, but also for expansionist reasons, was part of the plan from the very beginning, even before partition was adopted.

But right up to the moment that Israel was established as a state in mid-May 1948, Israeli forces were advancing all over the country. Cities like Jaffa and Haifa had been overrun, their populations expelled—60 to 70,000 people in each case. Smaller towns, same thing. Maybe 30,000 Arabs lived in West Jerusalem together with a much larger number of Jews. Israel overran the population and expelled them. This was in areas that were supposed to be part of the Arab state, or which were supposed to be part of the Jewish state but where the Arab population was supposed to be able to live in peace.

Now this is part of a war that was going on. But it was a lopsided war between a modern army backed politically, diplomatically, and financially by the United States and the Soviet Union and a disorganized and weak Palestinian resistance. It was no contest by the time the State of Israel was established in 1948. The Arab armies finally move in when Israelis have basically crushed Palestinian resistance, and then Israel, over time, is able to defeat the various Arab armies, of which really only two were serious contenders, the Egyptian and Jordanian armies.

Robinson

And over the course of the next several decades, Israel does engage in successive expansionist wars. There’s usually a pretext as to why the war has to be waged, but it repeatedly ends up with more territory coming under Israel’s control.

Khalidi

In 1956, Israel attacks Egypt, together with Britain and France. In 1967, Israel attacks Egypt, Syria, and Jordan, with the support of the United States. I go in great detail into the fact that in 1967, the United States was convinced, first of all, that the Arabs wouldn’t attack and secondly, that if they did, they would be crushed. So Israel is in no danger of elimination or annihilation or a new Holocaust, even though many Israelis believed that and many people in the United States were conned into thinking that that was the case, and that [the Six-Day War] was essentially a pre-emptive war. The Arabs had mobilized but they were incapable of winning that war, according to what American intelligence and American military assessments at the time indicated. In 1973, Israel was attacked by Syria and Egypt. That starts as a defensive war. But it’s a defensive war in a situation where Israel is insisting on holding on to occupied territory, and Egypt and Syria are fighting the war solely to liberate the occupied Sinai peninsula and occupied Golan Heights. They’re not fighting a war to destroy Israel, they’re not fighting a war to reverse the results of the 1948 War. So this is a defensive war on Israel’s part.

1982 is another war which Israel launches. They had been completely quiet on the northern border for 11 months when Israel attacks Lebanon in 1982. So most Israeli wars with again, the exception of ‘48 and the exception of ‘73—but ‘56, ‘67, ‘82, are essentially Israeli wars of expansion or aggression. Obviously, there are important pretexts, but they fit your description.

Robinson

And since 1967, when Israel took over the West Bank, the Palestinians have been living under this continuous state of military occupation.

Khalidi

Exactly. Well, it can be argued that what happens to the Palestinians who remain inside Israel—a couple hundred thousand—is occupation. They’re under military rule from 1948 until 1966. They cannot move without permits. So Palestinian citizens of the State of Israel have their lands taken away under various laws that are passed. They’re unable to move. The secret police, Shabak, controls their actions, their movements, surveils them, and so on. It is an occupation of the Arab parts of the country. And all of the land that is taken in this period is Arab land. In 1948, Jewish ownership of land was about 6 percent. Six percent of the land of Palestine was owned by either individual Jewish owners or by agencies of the Zionist movement. They basically steal the rest after 1948. Anyone who had left the country is described as an “absentee.” Their property becomes “absentee property.” The 750,000 Palestinians forced to leave what becomes Israel in 1948 are deprived of all their property, their fixed property, their mobile property, their furniture, their rugs, their books, their homes, in addition, of course, to their lands and their businesses and their bank accounts, I mean, everything is stolen.

Robinson

Readers of your book might be surprised by how critical you are of many Palestinian leaders over the years, in their efforts at negotiation. You do point out that one challenge for the development of effective Palestinian resistance is that there has been a long Israeli program of assassinating, deporting, and jailing effective Palestinian leaders.

Khalidi

Right. They killed as many as they could of the good ones. They left a few miserable characters who were either noxious or not considered effective. Palestinian leadership was very, very flawed. The elite leadership of the ‘20s, the ‘30s, and the ‘40s, in my view, failed miserably. They were perhaps facing an impossible task. They had the British, the League of Nations, and a very well-financed, well-organized, well-motivated Zionist project to deal with. They had the support of Arab public opinion, but the Arab countries were under colonial rule. The Arabs couldn’t do very much in the ‘20s and ‘30s, into the ‘40s. So they were facing an uphill task.

Nevertheless, I think they performed very poorly. And I argue in the book that that was partly because of the class nature of this leadership, its lack of democratic roots. It’s a failure born of fear of mobilizing the population in certain ways. And a variety of other failures. These were people who by and large didn’t understand international politics. Very, very few of the leadership and even fewer of the population were familiar with European countries or the rest of the world. They didn’t speak foreign languages, as against the Zionist movement, all of whose leaders came from Europe or the United States, and were native Americans, native Russians, native Germans, native Europeans. They were part of the political culture of Europe and spoke the languages. Abba Eban is a perfect example. Golda Meir grew up in Milwaukee. These are people who understood Western political culture and how to make that system work for them in a way that Arab leadership in Palestine simply did not.

So they were facing an uphill task but they nevertheless performed poorly. I would argue that the same is true to a certain extent for subsequent leaderships. The PLO [Palestine Liberation Organization] had some successes, but it had many failures. And I go into some of them in the book. Again, some of the failures are a function of their lack of understanding of certain aspects of the international arena.

Robinson

There have been many attempts in the United States and Israel to make Palestinians completely unpalatable and impossible offers and then characterize Palestinians as unreasonable, uncompromising “rejectionists” when they won’t accept the offer.

Khalidi

That’s a trope that goes back to Abba Eban: “Never miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity.” There weren’t very many opportunities. There might have been one or two. I talk about the 1939 White Paper. It was a very limited opportunity. The Palestinians, in my view, were very foolish to fail to accept it. There might have been other opportunities. I was involved in the negotiations at Madrid and Washington [in the early 1990s] with an Israeli delegation in which we tried to achieve self-determination and statehood. And that was something that was systematically denied us by the ground rules laid down by the United States at the behest of Israel. The same ground rules ended up governing the Oslo process later on. So there was no opportunity there.

It turns out, I argue in the book, and I’ve argued elsewhere, that the maximum that would be offered, has ever been offered to the Palestinians, is some form of autonomy under Israeli sovereignty with complete and absolute Israeli security control. Israelis would have control of the borders, the airspace, the land, and the water under everything that Israel was willing to offer under every Israeli government. I go into Yitzhak Rabin’s shift in his willingness to accept the existence of a Palestinian people and his willingness to negotiate with the PLO. But even Rabin in his last speech made it very clear that there would never be a Palestinian state.

So self-determination, statehood, and independence are ruled out by the Americans and Israelis, then and now, I would argue. So what are we talking about? You can pick up your own garbage, but we’ll arrest anybody we want, any time we want, to torture them, beat them up, and drag them off to our jails. And we’ll do it to anybody who resists our dominance, and we make all the laws, and you obey our military rules. What kind of “state” is that? That’s not a very good deal.

Robinson

Let me dwell on this because it seems critical. To the extent that there has been talk of a “two state solution,” what has actually been on the table consistently in every negotiation for the last 50 years has never involved a concession by the United States and Israel—they negotiate together—that Palestinians should have anything that we would consider to be equivalent to a state in the sense that other states are states.

Khalidi

The United States talks the talk, but it will not walk the walk. It will never say “this outcome has to include complete and absolute Palestinian independence.” It will never impose that in Israel. It will never lay that on the table as the outcome that has to be reached.

There are some Israeli governments that came closer to this than others. Rabin came closer. But none of them would have accepted the idea that Israel would give up its security control, that Israel would cease to control the borders, that Israel would cease to be the only sovereign power. I mean, if you don’t have your own army and your own borders, and your own economy, and your own ports and your own airports and your own airspace, you’re not sovereign. You’re not independent. You’re a dependent subunit of a larger sovereign state. And that’s all that Israel has so far been willing to offer. The United States has never pushed it to do anything more than what Israel was willing to do. The deference of the United States to Israel is limitless.

Robinson

An associate of Benjamin Netanyahu once said that the Palestinians could call whatever Israel was willing to give them “a state” or they could call it “fried chicken.” In other words, Israel was happy to give Palestinians something they could call a state if they wanted to, but what mattered was the balance of power.

You’ve talked about the role of the United States in the continuing denial of Palestinian self-determination. The implication is that altering U.S. public opinion and then U.S. public policy is pretty critical if we are ever going to see the Palestinians granted that right to self-determination in some part of their former country.

Khalidi

I think you’ve put your finger on something absolutely crucial. If we look at the political map today, we see the United States putting its large thumb on the scales in favor of Israel in every circumstance. In the United Nations, in terms of arming it, in terms of financing its military to the tune of over $4 billion, in terms of a huge river of tax-free 501(c)(3) donations, which fuel the settlement movement, fuel the aggressive stealing of Palestinian land, and on which Israel floats. The amount of money that goes to Israel from the United States is not just what taxpayers are paying. It is also people not paying taxes by contributing to 501(c)(3)s that are doing things like supporting the Israeli army. “Friends of the IDF” is a 501(c)(3)! As are multiple institutions that support settlements all over the occupied territories. That’s the situation on the ground.

If you look at it theoretically, and you understand Israel as in some respects both a nation-state and national project, but also a settler colonial project, the United States and Europe are the metropoles. And without them, this project would have enormous difficulty. That’s why Chaim Weizmann went to the British and managed to sell them on the idea of a Jewish state and Palestine. He understood that you needed a grand imperial sponsor. First it was Britain, and eventually it became the United States.

So what happens in the United States is crucial. And one of the interesting phenomena in the last decade or so, is that you’re beginning to see a shift in some parts of American public opinion, away from blind, uncritical swallowing of any nonsense that the Israelis put out. It’s moving to a more nuanced, more critical, more informed understanding that there is a Goliath, which is Israel. And there’s a David, which is the Palestinians. And it’s not the other way around. The Palestinians are under occupation. And Israel is denying them their rights.

Now, this is not a majority view in the United States by any means. But nobody thought that 50 or 30, or even 20, years ago. Today, you have a couple dozen members of congress who express views that go quite counter to the established false narrative, which the leaderships of both the Republican and Democratic parties are still completely committed to. This is new. This never happened before. Today, you have dozens of American campuses where the students have voted in favor of boycott, divestment, and sanctions. That is a symbolic step, but it’s an indication of a shift in public opinion. You have independent media which are talking about things that were forbidden. You could not show or say certain things most of the time about Israel and the Palestinians. The mainstream media still is terrified—as your own experience with the Guardian indicates—of saying certain things, whether it’s television networks, the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Guardian, or Reuters and AP. But non-mainstream media and social media are much more open. And most young people don’t know the New York Times from a hole in the wall. They don’t care about Fox or CNN. That’s not where they get their information. So there’s a much freer flow of information, and I think that has dislodged a large number of fixed ideas in the minds of younger people. That’s an important shift, I think, for the future.

Robinson

I think that’s right. Some of the dynamics of the conflict are more accurately understood. But a lot of the history you lay out in The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine is very much still buried. I think people really don’t grasp what Palestine was, what the Zionist enterprise was at the beginning, and how the situation came about in the first place.

Khalidi

Every part of the title, and the book itself, is dedicated to challenging the false received version of that history. This is not a war between two peoples on the basis of equality. It’s not France and Germany. This is a war on Palestine. It’s not just a war waged by the Zionist movement in Israel. It’s a war waged by Britain, by the United States, by the Soviet Union, by Britain and France, on the Palestinians. It’s not just the renaissance of the ancient Israeli state. It’s a national project, with a Jewish ancestral link to the land of Israel, but it is also a settler colonial project, by its own description. And if you compare it to other settler colonial projects such as Ireland or Algeria, you see all the parallels. And you see that what the Palestinians are doing is not engaging in terrorism. They’re engaging in resistance, whether one likes their means or doesn’t like their means. And I think that each part of the title of the book, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, is a reference to one or another aspect of that challenge to the false received version of history.

Robinson

When you said the Palestinians are not engaging in terrorism, one important point is that various means of resistance are denied them. You’re very critical in the book of attacks on civilians. But at every stage, the available ways that Palestinians can fight back have been constricted, and those things that horrify us come out of that.

Khalidi

I think there’s another point to be made. I argue in the book that various forms of armed action, including, especially, attacks on civilians, are horrific, immoral, and, very importantly, politically counterproductive. I go into this in some detail at one point in the book. But it has to be said that slaughtering civilians is slaughtering civilians. When Israel kills 16 children and five women in Gaza, using 2000-pound bombs and Hellfire missiles, if you don’t describe that as terrorism, and you describe the death of an Israeli child or an Israeli woman or another Israeli civilian as terrorism, this is Orwellian language. You are simply using the word “terrorism” as a bludgeon to demonize Palestinian resistance, whereas somehow the murder of children in Gaza … 16 kids were killed in these attacks, five women were killed in these attacks. Heaven knows how many other civilians were killed. Maybe a dozen militants were killed? I don’t know. But 30 or so civilians were murdered. If that’s not terrorism, then the word has no meaning. And this happens every single time. There were 240 civilians killed in one of these attacks a few years ago. Each time the toll is equally lopsided. Why are attacks on civilians not considered terrorism? If you use the same measure, I have no problem with the use of that term. But then you have to describe the use of Hellfire missiles and F-16s and heavy artillery in the same way. In the book I go into the kinds of weapons that are used by Israel— the artillery, the missiles, the aircraft, the helicopters—and the indiscriminate nature of the attacks on a population of a couple of million people in a tiny area. If that’s not terrorism, I don’t know what is. But of course, the term is only applied to the Palestinians. Somehow Ukrainian resistance is not terrorism yet Palestinian resistance is. I repeat, I think the killing of civilians is wrong and immoral. It’s a violation of international law. But if that’s true for the Palestinians, certainly it’s true for the Israelis as well and on a much larger scale.