The Quit-Lit Pseudoscience and Faulty Feminism of Women’s Sobriety Memoirs

Vulnerable women in recovery deserve better than books written by authors peddling expensive products and services and promoting consumption instead of evidence-based treatments.

Alcohol poses an ever-increasing threat to women’s health and the quality of their lives. In 2019, 4 percent of women in the United States had an alcohol use disorder, and 13 percent of adult women binge drank several times each month. Approximately 1 out of every 20 pregnant women binge drinks while pregnant. In recent years, beverage corporations have aggressively pursued women by linking alcohol with breast cancer awareness pink ribbons (also known as “pink washing”), promoting “skinny” drinks, and posting social media content that conflates drinking with female empowerment. Alcohol presents even more serious problems for women of color and of lower socioeconomic status, as these women are far less likely to receive treatment and experience greater stigmatization and discrimination for substance abuse issues. Sexual minority women face even greater risks; they are seven times more likely to meet the criteria for alcohol dependence compared to heterosexual women.

If you go to your local library or bookstore and peruse the psychology sections, you are likely to come across at least a couple of books about addiction written by women who have journeyed through sobriety. A close look at more than a dozen books in this genre, all of which I initially read in my first sober year, reveals themes of work and family stress, eating disorders, childhood trauma, sorrow, anger, and, in many cases, success in recovery.

One noticeable problem with the genre is that it ignores the socioeconomic and racial realities of alcohol dependency among women in the U.S. While Americans with higher socioeconomic status use alcohol at similar rates or even more often than those with fewer financial resources, people with lower socioeconomic status often face greater consequences for drinking, including loss of employment, health complications, arrests, and convictions. Women with more resources can hide their drinking more easily because they experience less scrutiny and greater autonomy at work, can pay for childcare and grocery delivery, and can afford ridesharing services when going out at night, minimizing their risk for employment, family, and legal challenges as a result of their drinking. In contrast, women in poverty bear the burden of psychological distress due to not only their lack of economic resources but also because of neighborhood violence, which increases their risk for alcoholism. White female drinkers who live in poorer neighborhoods, when compared with those in wealthier ones, typically have more alcohol-related family trauma and use drugs at higher rates. Additionally, white women are significantly more likely to receive treatment for substance use disorders than Black and Latina women, even those with similar socioeconomic and insurance statuses. Further barriers for women of color include lack of childcare and valid concerns about being reported to child welfare agencies, which tend to target Black and Indigenous families disproportionately.

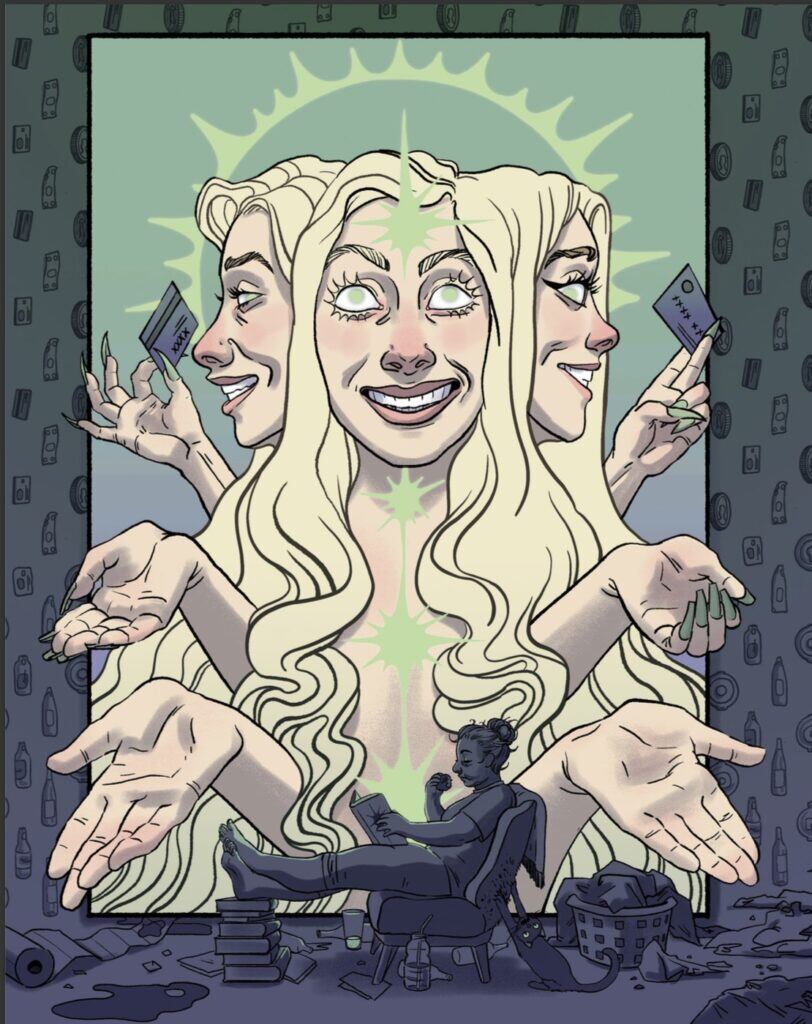

Additionally, top-selling books are not rigorously fact checked (a serious problem in the world of nonfiction books), and authors often mix discussions of legitimate science with quackery or unproven practices, which is outright dangerous for the non-discerning reader. Authors in this genre also tend to appropriate the language of social justice (rallying against capitalism, patriarchy, and so forth) to make readers think that tackling their alcohol problems (or doing self-care) equates to a larger project of social change. These writers cleverly create a trail of breadcrumbs that leads vulnerable readers to programs such as expensive online courses and coaching services and related products and services, many of which are offered by the authors themselves. Aspirational big-money lifestyles are highlighted while effective programs like Alcoholics Anonymous are trashed. Most dangerous of all, this consumptive approach to alcohol dependency treatment makes products a substitute for healthcare from a qualified mental health professional.

In 2021, the year I quit drinking, I spent a great deal of time walking around my neighborhood in the fog of early sobriety, headphones in, the words of self-help writers rolling into my ears. I found this practice an effective way not only to burn off the sugar from all the boxes of Entenmann’s donuts I consumed but also to fill the time between managing my antipsychotic medications, attending therapy appointments, napping, and watching The Sopranos.

I’d first forayed into the women’s addiction genre in the early-aughts, when I came across a copy of Caroline Knapp’s Drinking: A Love Story in a thrift store. I purchased Knapp’s memoir for $2, and I read it nearly a dozen times in the span of a couple years. The book offered numerous scenes of the type of drinking I loved to do. Alone at a bar. With a close friend at a bar, stumbling into the bathroom and back, then having another and another. All-weekend binges with someone who drank more than I did, who made me say to myself, “At least I’m not as bad as my sad sack friend. I can handle my drinks.” And, my favorite: drinking glass after glass of wine while whipping up some elaborate meal.

At that time, I went out every night to either attend rock shows or perform in them with my band Anti-Love Project. I routinely consumed anywhere from four to more than a dozen drinks a night. I felt tough that I could keep up with the boys around me, but I also secretly worried about my penchant for self-destruction and the days I strung together sleeping in bed in the pitch-blackness of depression.

Almost all of Drinking: A Love Story, with its romanticized scenes of alcohol consumption alongside Knapp’s maintenance of her writing gig at the Boston Phoenix, seemed adventurous and so realistic, a map for my possible future. Except for the part at the end when Knapp goes to rehab and meets up with friends at coffee shops, which sounded extremely boring. Even after a stint in the emergency room, which landed me in the dual-diagnosis unit at McLean Hospital—the very place made famous by Girl, Interrupted—I remained loyal to my favorite substance. I would never give up on my drinking like Caroline did. Or so I thought.

Fast-forward to 2021 when, newly dried out, I purchased the audiobook of Drinking: A Love Story. From there, I bought the next suggested title and then the next one. Leslie Jamison’s The Recovering: Intoxication and Its Aftermath seamlessly weaves Jamison’s personal story and surgical self-analysis with a breadth of research about alcohol-fueled literary geniuses and the history of Alcoholics Anonymous. Cat Marnell’s whiplash addiction memoir How to Murder Your Life took me on a wild ride through her relatable anxiety-powered bouts of creative sundowning and offered up fascinating insider tidbits on the New York fashion and beauty world.

Several of these books serve as an entry point into the authors’ online courses, meetings, and coaching services.1 Laura McKowen’s We Are the Luckiest allows you to continue your journey in her online Luckiest Club for $242 per year. Holly Whitaker’s Quit Like a Woman: The Radical Choice to Not Drink in a Culture Obsessed with Alcohol leads to the Tempest Sobriety School for $59 per month. (Tempest partnered with Syracuse University in a study to test the program’s effectiveness, which found that the program resulted in positive changes in mental health and reduced alcohol and drug use in the fraction of participants who fully completed the study. However, the fine print shows that Holly Whitaker co-authored the study and Tempest funded it.) Annie Grace, who wrote This Naked Mind, has a free 30-day sobriety program, but beware the upsell. She charges $197 for 100 Days of Lasting Change, and $997 for a full year of The Path: Freedom Accelerated. Sober vegans who delight in Rebecca Weller’s A Happier Hour can participate in her Sexy Sobriety program for $799 per year.

In recent years, healthcare professionals have shown increasing interest in online programs and apps for the treatment of substance use disorders, due to their cost-effectiveness, accessibility, and wide reach. However, these electronic interventions work best when they are empirically tested, supported by mental health professionals, and used in conjunction with traditional therapy sessions. The rogue courses developed by private for-profit entities tend not to have such features. In fact, the Luckiest Club, Tempest, and This Naked Mind all have disclaimers on their websites stating that their personnel are not licensed medical professionals.

We Woke

An important feature of the genre is the way the authors build emotional intimacy with the reader. Both Whitaker and Grace strategically use first-plural pronouns (we, us, and our) to promote the idea that we’re all in this together. For example, in the introduction of Quit, Whitaker claims that her book is “about our power as women—both as individuals and as a collective,” bonding us all together as we move through Whitaker’s 300-plus-page infomercial. The last paragraph of This Naked Mind reminds the readers that buying into Grace’s ideology means that “we save ourselves and prepare this amazing planet and all its incredible inhabitants for the next generation for our children.” We have joined the club and are now part of saving the world for the imaginable future. This very skillful use of language belies the fact that the authors seek to turn a profit from the reader by encouraging consumption. How more consumption translates into “saving the planet” is unclear.

Both authors also appeal to a reader’s sense of powerlessness against big corporations that dominate every aspect of modern life. Quit Like a Woman and This Naked Mind, for instance, got me the most riled up to fight the battle against both Big Alcohol (the mega-corporations such as Anheuser-Busch, Coors, and Heineken that aggressively market the poisonous beverages they sell) and Big Sobriety (the unregulated for-profit rehabilitation companies that aggressively market their expensive treatment centers despite the fact that they don’t actually offer medical care). Whitaker convinced me that my own personal sobriety could stick it to the man: “the capitalist patriarchy” of Big Alcohol’s “assloads of money and power and access.” Whitaker appealingly connects the act of quitting drinking to the “ascension” of “women and other historically marginalized individuals.” She poses the question: What would happen if we all rejected alcohol? According to Whitaker: “world domination, bitches.” (What she means by this, however, is never elaborated upon.)

Whitaker condemns the patriarchy, but her book has multiple references to people who allegedly committed sexual abuse against women and girls. For example, she quotes the late yoga guru Yogi Bhajan (yoga historian Philip Deslippe said he would be remembered as the “Harvey Weinstein of Yoga,” and the New York Times referred to him in 2004 in an obituary as the “‘boss’ of worlds spiritual and capitalistic”), seemingly unaware of claims that he had been accused of physically, sexually, and emotionally abusing women and children. She also repeatedly cites “integral philosopher” and climate denier Ken Wilber (who, according to a 2008 Salon profile, held “out the promise that we can understand mystical experience without lapsing into New Age mush”) despite his partnership with spiritual leader Marc Gafni, a yoga teacher and former rabbi accused of sexual assault of a teenage girl.

Another passage in This Naked Mind appears to sympathize with college rapists who commit their sexual assaults while drunk: “The majority of college rapes involving alcohol are not planned. These boys don’t intend to become rapists. In a major study, a boy who forced sex on a female friend wrote, ‘Alcohol loosened us up and the situation occurred by accident. If no alcohol was consumed, I never would have crossed that line.’”2 It’s jarring to read someone who claims to want to empower female readers citing such harmful characters.

Whitaker then rails against the collective oppressions of “poverty, racism, sexism, homophobia, ageism, classism, ableism.” My own experience primed me to see Whitaker’s proclamations as important. As a veteran bilingual teacher in the Boston Public Schools, I have witnessed the effects of these -isms on my new immigrant students in terms of homelessness, medical care, and food access. But it was plain to see that Whitaker’s equating of sobriety with social justice held no real weight; rather, Whitaker dabbles in equality to further her own self-improvement, rather than committing herself to real means of changing society.

Whitaker writes that she has “gone to a number of antiracism workshops that [she] would count as not just ‘personal development’ but ‘societal and cultural development.’” This seems a bit like checking these items off a list. In the style of Black-People-Love-Us (a satirical website featuring a fictitious preppy white couple boasting about their crew of Black friends), she namedrops her activist “friend” Rachel Cargle, founder of the Loveland Therapy Fund which (unlike Tempest) takes action against racial disparities in mental health care by financing these services for women of color.

She further boosts her own equality cred by trying out a protest, the 2017 Women’s March in Los Angeles, where she was broadly “protesting (for or against) all the things: the NRA, reproductive rights, diversity and inclusion.” She even advises the readers to do this little experiment for themselves: “If you’ve never been to a protest, check one out.” While it’s certainly commendable to go to a protest in support of your beliefs and to encourage others to do the same, the effort here seemed lacking in a deeper commitment to involvement in organizations that do the hard work of improving people’s lives in concrete ways.

What’s more troubling, however, is the following: in the last paragraph of Quit, Whitaker draws parallels between the Stonewall Riots (throwing in a mini history lesson: “a group of queer and trans people fought back against the harassment of the LGBTQIA community by the NYPD”) and the “revolution” that Whitaker herself began in a bar. She bases this comparison on the fact that she wrote the final words of her book on June 28, the anniversary of Stonewall. The suggestion that her individual experience resembled those of the Stonewall rioters is simply bizarre.

If Whitaker were serious about combating the societal injustices she cites, she would be better off advocating for policy changes such as expanding community-based prevention programs and access to medical care. Instead, she spends a good portion of her book outlining all the products and services she consumed in her sobriety journey and ultimately leads the reader to services from which she will make a generous profit.

Consumers Are Us

The first chapter of Quit reads like a consumer superhero origin story. At the tender age of 13, Whitaker visits her cousin, an accountant, and lusts after her fancy home in an exclusive neighborhood with “the best schools” and fondly remembers her “first Starbucks.” As a young adult, Whitaker wants nothing less than “money,” “ status,” and “purity” (whatever that means). She admiringly watches Pirates of Silicon Valley and lands a job in a “Big Four” accounting firm.

Whitaker details the investments she made in “treating” her own sobriety, including massages at the Kabuki Spa ($120-170), amino acid therapy ($139 for 90 min.), Kundalini yoga teacher training ($200-$7,000), sound therapy ($80 to $500 an hour), and even a two-month trip to Italy to celebrate quitting her corporate job à la Eat Pray Love. In total, Whitaker “spent thousands of dollars on therapy and programs and acupuncture and health care and vitamins and gurus” including a “magical” therapist who “wasn’t fucking around … charged $250 a session” and “didn’t scrap with insurance.” Basically, in Whitaker’s world, less-costly insurance-taking therapists just yank our cranks and we should all be asking ourselves: why save when we can spend?

Whitaker clearly has a specific audience in mind, perhaps the sort of woman who can consume her way to social justice the way Whitaker consumes her way to personal wellness:

“We buy organic. We use natural sunscreens and beauty products. We worry about fluoride in our water, smog in our air, hydrogenated oils in our food, and we debate whether plastic bottles are safe to drink from. We replace toxic cleaning products with Mrs. Meyer’s and homemade vinegar concoctions. We do yoga, we run, we SoulCycle and Fitbit, we go paleo and keto, we juice, we cleanse. We do coffee enemas and steam our yonis and drink clay and charcoal and shoot up vitamins and sit in infrared foil boxes and hire naturopaths and shamans and functional doctors and we take nootropics [drugs to enhance cognition], and we stress about our telomeres (those are all real words). We Instagram how proud we are of this and follow Goop and Well + Good and drop forty bucks on an exercise class because there are healing crystals in the floor.”

Who exactly belongs to this particular class of “we”? Certainly, not me, a middle-class public school teacher and mother of three. The only “real” people I knew of who do all these things are The Real Housewives.

And it’s hard to say which is more troubling: that Whitaker’s hyper-consumptive regimen of (mostly) pseudoscience3 is so extreme, or that some readers may find it aspirational.

Is Alcoholics Anonymous for Idiots?

Quit Like a Woman and This Naked Mind have extremely flawed takes on Alcoholics Anonymous, presumably because the Big Book by Alcoholics Anonymous, an organization with “several million members in 181 countries,” is part of their competition for clients. And AA’s price point of free certainly can’t be beat. (Both Quit and This Naked Mind also fail to mention employer-based initiatives. For example, the federal Family Medical Leave Act allows 12 weeks of leave for addiction treatment. According to U.S. Bureau of Labor statistics for 2021, 55 percent of U.S. employees had access to Employee Assistance Programs through which licensed professionals provide confidential mental health services at no cost to employees.)

Both Grace and Whitaker take issue with AA’s adoption of the disease model of addiction—meaning the classification of alcoholism as a medical condition. While it’s one thing to object to a label—both authors claim that the program forces its members to unnecessarily label themselves as alcoholics—the reality is that alcohol use, especially heavy and prolonged alcohol use, does cause serious medical diseases such as alcoholic liver disease (which can lead to a more severe form called cirrhosis) and alcoholic neuropathy, as well as a heightened risk for numerous cancers. Grace cites Dr. Lance Dodes’ controversial claims that that AA only works for a small percentage of its members and that “spontaneous sobriety,” or forgoing any type of treatment whatsoever, has four to seven times more effectiveness than AA. In Quit’s sixth chapter, titled “AA Was Created for Men,” Whitaker argues that AA tells women and people from other marginalized backgrounds “to renounce power, voice, authority, and desire” and characterizes addicts as “egocentric selfish liars” while asserting that “women [need] a different approach,” presumably the one designed by Whitaker herself.

However, a 2020 literature review published in Alcohol and Alcoholism by researchers from Harvard Medical School, the Stanford University School of Medicine, and The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction finds that AA attracts “a diverse membership of women and men from a wide range of racial and ethnic backgrounds.” While AA and other outpatient treatment programs had comparable effectiveness in areas such as periods of abstinence and number of drinks per day, AA resulted in higher abstinence rates and greater cost-effectiveness. A 2012 study in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence acknowledges concerns around the concept of “powerlessness” (the first of AA’s 12 Steps is that “We admitted we were powerless over alcohol— that our lives had become unmanageable”) and male pronouns in AA’s literature with regards to the possible disenfranchisement of women. However, the article indicates that philosophical concerns “have not been born out empirically,” as women comprise a third of AA members and multiple studies also show that women in AA benefit as much or more than men.

Quit acknowledges that “Alcoholics Anonymous was truly revolutionary, the first organization that helped people stop drinking on a mass scale.” But ultimately she reduces it to a “simple program that any idiot could do who had two cents and some humility.” You don’t even need a pair of pennies to sit in an AA meeting; all you need to do is show up. But remember: free doesn’t cut it for Big Spender Holly Whitaker.

What Me Science?

In reading these books, I was struck by an initial red flag that came from something so small that it could be attributed to an innocent error or typo. In Quit, Whitaker claims that the final season of Mad Men was set in 1976 even though it was actually 1970. Since something so easy to fact check hadn’t been, I became suspicious. I didn’t have to go far to find other problems where the authors skipped over nuance or offered contradictory takes. For instance, Grace’s This Naked Mind contains a too-good-to-be-true claim about heroin users from the Vietnam War. Grace claims that American GIs who used heroin in Vietnam easily quit “with almost no withdrawal symptoms” because they had reunited with their families. The case of the Vietnam GI heroin users has been cited by writer Johann Hari, who has emphasized the role of a person’s environment in his writing about the science of addiction. However, studies in accredited medical journals offer more nuance, noting a range of factors with regards to heroin addiction and recovery: snorting/smoking versus injection, concurrent psychiatric illness, rehabilitation overseas before soldiers re-entered the U.S., race, and pre-Vietnam drug use.

Whitaker’s takes on science and medicine are confusing for the average reader and demonstrate a lack of critical thinking. She has a real bone to pick with science and medical authority figures. While subjecting authority figures to healthy skepticism is indeed good, Whitaker’s takes are thin on substance. She won’t believe health claims “just because they came from a medical doctor or scientist’s mouth.” If credentials don’t confer legitimacy, what does? (We’re not told.) She objects to the “the classification of alcoholism as a disease,” arguing that addiction stems from “an increasingly dislocated capitalist society, not from medical pathology.” She then contradicts herself by acknowledging that “the disease model has been upheld by recent advances in neuroscience and is what the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institutes of Health endorse: addiction means that the brain is diseased chronically.” It should be noted, of course, that the conditions of life under U.S. capitalism are increasingly harsh for the vast majority of people. The U.S. has record inequality, worsening inflation, falling life expectancy, poorer health outcomes compared to other wealthy nations, dystopian working conditions for the working class, and an opioid crisis, just to name a few problems. Whitaker fails to acknowledge that while the environment (“capitalism”) impacts our health and behavior, it’s also a leap of logic to say that to critique capitalism means we ought to reject medical science.4

She peppers Quit with a fair number legitimate scientific and academic sources, such as the Center for Disease Control and National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence. But she also legitimizes unproven or less well accepted complementary or alternative medicine theories and practices such as gut-healing for “leaky gut” and meridian-point tapping (a highly variable practice that can be traced back to traditional Chinese medicine). She cites incredibly problematic sources such as Dr. Dharma Khalsa, who peddles unapproved Alzheimer supplements online. She argues that “addiction is a dysfunction in our first chakra” and quotes experts in “medieval women’s mysticism” who (however justifiably) warn readers of the harms of the “fashion industry” and “pornographers.”

She takes a jab at Oprah for spending her “precious Weight Watchers points on wine,” but plenty of her own sources have been propped up by Winfrey’s so-called junk science queendom (Winfrey has given figures like Dr. Oz and Jenny McCarthy, among others, platforms to spread their sensationalist and scientifically false claims on, respectively, health cures and vaccines). Several of Whitaker’s New Age influences have connections with Oprah, including spiritual teacher Eckhart “Thinking has become a disease” Tolle, Marianne “sickness is an illusion” Williamson, and Pema Chodron, a Buddhist nun and alleged sexual abuse denier.

In This Naked Mind, Grace also references Tolle and Chodron. To her credit, Grace has some intriguing tidbits from legitimate scientists and works of public health research such as public policy professor Philip J. Cook’s Paying the Tab, a survey of the socioeconomics of alcohol, and neuroscientist Thad Polk’s explorations of the role of genetics in addiction. But she then cites Jason “the Juice Master” Vale, who promotes 800-calories-a-day diets and argues that there is no such thing as alcoholism. Grace states that “a growing body of research suggests that our unconscious minds cannot actually tell the difference between a real experience and a vividly imagined fake experience,” and, indeed, the book’s endnotes cite the source of this mind-boggling statement about the subconscious as a blog post written by self-proclaimed “brain-wave enthusiast” and sound engineer Lawrence Weller on his website.

With such an inconsistent jumble of sources from these authors, how is the reader to distinguish between what’s scientifically legitimate and what’s not?5

The U.S. healthcare system and medical profession certainly have a long way to go in terms of improving addiction medicine services, access to healthcare, and cost of care. So it’s understandable that people would seek out complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), or practices that fall outside of mainstream medical practice. The latest government statistics from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey reveal that 3 to 18 percent of Americans reported using some form of CAM. One 2017 paper based on the 2012 survey data found that nearly 40 percent of people with mental health needs used CAM to treat conditions including anxiety and depression due to needs unmet by conventional practices. Acupuncture, meditation, tai chi, and yoga have all been found to improve symptoms of mental illness. Yet CAM acceptance among medical practitioners remains uneven and confusion around whether Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations apply to CAM-related products remains a problem.

At minimum, authors tackling such complex subject matter probably need co-writers to help them break things down for the reader and explain which practices have a scientific basis (and which don’t) and which are safe (or harmful). What’s more, I find it especially troubling that, despite their dubious sources, both Tempest and This Naked Mind offer sobriety coaching services that may be viewed by readers as a substitute for therapy or medical care.

Coaches: More Than Just “Glorified AA Sponsors”

Recovery coaching is a kind of life coaching geared to help people who are recovering from conditions such as mental illness or substance abuse. All 50 states offer Peer Recovery Coaching Training and Certification programs that generally cost a couple hundred dollars. Graduates of these programs must meet requirements for coursework, certification exams, and supervised practicums. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics considers such workers to be community health workers. The 2021 median pay for workers in this field was $37,610.

Recovery coaching is also big business. As Kelly Fitzgerald, who became a coach after being laid off from her content creation job, writes in a 2019 article on Tempest’s website, “What is a Recovery Coach?”: “According to the International Coaching Federation, in 2016, there were 17,500 coaches in North America who generated over $955 million,” or almost $55,000 per coach.

For-profit private coaching remains largely unregulated. Coaches operate independently with little oversight. When sobriety coaches are not integrated with licensed mental health professionals, they can easily get in over their heads, especially when it comes to clients who need advice on medication, who face relationship issues and financial struggles, and who feel suicidal.

This Naked Mind, the program affiliated with author Annie Grace, trains its own Certified Recovery Coaches (one GoFundMe fundraiser in 2020 asked for $15,000 to pay for the training fees for one person), and upon graduation, coaches are listed in the online coaching directory. In a business model that whiffs of multi-level marketing, the coaches operate their own independent businesses. The website of one of these coaches sells jewelry and yoga classes and charges $65 for a 45-minute phone call. Another, a former lawyer, began her coaching business as a way to find work-life balance after becoming a parent. In an e-mail exchange with Annie Grace’s public relations representative, I directly asked about the qualifications needed to become a coach, but this question went unanswered in the rep’s reply. Tempest, associated with Holly Whitaker, offers coaching sessions that cost $75 per half-hour, and their coaches past work stints include jobs as creative writing teachers, yoga instructors, and public relations and marketing strategists. These people are not mental health professionals.

Fitzgerald, who wrote the coaching article for Tempest, reinforces the more-money-equals-better-than concept by critiquing the free-of-charge AA sponsors who fail to “invest in” recovery and merely “share their experience, strength of hope with others.” Fitzgerald’s coaching credential from the International Association of Professional Recovery Coaches (which requires no application other than a $2,897 payment) apparently makes her much more effective than the AA sponsors who do their “work” for free. As she puts it quite plainly: “No, I’m not a therapist or an AA sponsor, I’m a recovery coach. And, yes, of course, I charge for my services.” She also argues that recovery coaching carries less stigma than AA or psychotherapy, but this made me wonder whether the real work of those passionate about addiction recovery should focus on activism to reduce this stigma rather than to profit from it.

Accredited addiction rehabilitation facilities, such as South Boston’s nonprofit Gavin Foundation, offer coaching as a way to support clients in their transition from inpatient treatment to community reentry. John McGahan, Gavin’s President and CEO, explained to me the important role that coaches play in guiding people through everyday life after completing structured rehabilitation programs:

“In rehab, patients are given a schedule and a routine to follow. Someone instructs them on what to do at every moment. But when people only have 12-step meetings for an hour-and-a-half per day, they don’t know what to do with themselves. Coaches engage with them during inpatient and continue their services into the real world. Prior to having coaches, patients were just cut loose after rehab.”

Coaching is thus an important part of recovery. As with any aspect of healthcare, though, we need to question the for-profit nature of the care and the insidious blurring of coaching (as lifestyle consumerism) with addiction healthcare.

According to a 2016 Surgeon General’s Report, Facing Addiction in America, only about 3 percent of individuals with substance use disorder obtain treatment that meets minimal standards of care. The authors’ “Vision for the Future” chapter argues that we have not only a moral imperative to combat the disease of addiction but also an economic one. Addiction costs the U.S. “$442 billion each year in health care costs, lost productivity, and criminal justice costs.” To truly combat addiction in all its complexity (including socioeconomic and racial disparities), and to ensure better outcomes for all women, we need society to prioritize addiction treatment and prevention for all. Congress should pass the highly popular program Medicare for All, which would include mental health and addiction treatment for everyone at no cost at the point of care.

Furthermore, addressing the public health aspect of addiction would require

“expanding access to evidence-based treatment, offering wide-reaching community-based prevention and policies (including those that can be delivered in individual homes, schools, and community centers), full integration of addiction treatment into mainstream healthcare, and laws that increase access to services, and funding for future research.”

We also need widespread cultural change, shifting our society to one in which people who need help can seek it without fear of stigmatization, in which healthcare professionals demonstrate compassion for patients with addiction disorders at the same level as they would for patients with other chronic conditions, and in which addicted people are celebrated for their progress toward wellness.

We need to do a better job at prevention by addressing root causes that put children at risk for future addiction disorders. Adverse childhood experiences (also known as ACEs) such as abuse, neglect, mental illness, and domestic violence, among others, have been shown to create ‘toxic stress’ which puts children at risk for future medical conditions and social problems including substance abuse. Creating conditions to minimize ACEs would involve making sure everyone has the basic goods and services they need to thrive. This would include culturally responsive support for the youth living in poverty, increased quality of care for pregnant women and children, affordable housing, and increased early childhood education.

Books in the women’s sobriety memoir genre can be highly seductive. These authors create emotional intimacy with the reader while providing endless medical and scientific citations to establish expertise and authority. Mixed with Whitaker’s rallying cries of feminism and Grace’s supposed scholarship, all of it had me duped at first. As Johnny Rotten famously inquired at the conclusion of the Sex Pistols’ terminal performance: “Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated?” Yes, yes, I did.

Vulnerable women suffering from addiction deserve much better than shoddy books whose authors want readers to pull out their credit cards at the conclusion. I would love to see a book written by women such as Becca Lilly and Bernadette Calicchio, who run a needle exchange program in Wilmington, North Carolina; or Jess Tilley, who founded the New England User’s Union, a group that fights the stigmatization of drug use. This would ultimately require agents and publishers to provide advances so that women other than those at the upper echelons of economic privilege could have the opportunity to tell their stories of collective action in book form. At the very least, we need authors to promote programs that have been tested according to rigorous scientific standards and to promote critical thinking rather than saleswomanship in their readers.

While none of these sobriety product-peddling women authors hold degrees or certifications in the medical field, their prestigious educational and professional credentials may lead readers to believe that they possess greater expertise in healthcare than they really do. McKowen, a former Vice-President in a large public relations firm, holds a B.A. in Marketing as well as an MBA. Whitaker has a degree in Business Management Economics and formerly worked as a Revenue Director at One Medical, a membership-based primary care service. Grace held a position as Global Head of Marketing in the financial services industry and has a graduate degree in Business Marketing and Entrepreneurial Studies. Weller formerly had a corporate career and now serves as a brand ambassador for the Institute for Integrative Nutrition, which offers a Health Coach Training Program, open to anyone with at least a high school diploma or equivalent, for $6,995. ↩

The ‘drinking made me do it’ argument was also used by Stanford rapist Brock Turner. Chanel Miller made her thoughts about alcohol and rape clear in the victim impact statement she read aloud to Turner at his trial: “This is not a story of another drunk college hookup with poor decision making. Assault is not an accident.” ↩

Editor’s Note: This list of wellness interventions is extreme and there is a lot to unpack here. Here’s our medical editor’s take:

“Organic” is a label that is only as good as the certification process behind the label. USDA “organic” prohibits synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, some of which may promote the development of cancer. The label also means products “promote ecological balance, and conserve biodiversity,” which do sound like good things.

“Natural” for the most part does not have a standardized meaning. As food writer Michael Pollan points out, foods with the word “natural” on them often aren’t natural, and natural foods (fruits, vegetables) need no labels for us to know where they come from. For a discussion of “organic” and “natural” see Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma.

Fluoride has been in the water supply for decades because it helps prevent dental cavities. Excessive fluoride can cause tooth staining and other problems. Some people are concerned about fluoride and may opt to use fluoride-free toothpaste or drink water that isn’t from their municipal source. That seems reasonable as long as the potential anticavity effect of fluoride is acknowledged.

“Smog in our air” is a problem that all people should be concerned about.

“Hydrogenated oils” are often found in commercial baked goods or other processed foods (which are not healthy). It seems reasonable to avoid these fats.

Concern about plastic containers is reasonable and it seems harmless to avoid plastic containers.

Read about Mrs. Meyer’s here. Of note, fragrances and essential oils in these products can be irritating to the skin.

Running, yoga, SoulCycle, Fitbit: Physical activity is good for the body. If a device like Fitbit helps you be active, then that’s great. (But you don’t need a Fitbit or a specific cycle program to be active.)

Juicing: I can’t really recommend because it processes foods into a form where you are likely to consume more than you would if the food was in its whole form. And juicing can cause loss of pulp/fiber which is an important part of fruits and vegetables. Commercial juices may have added sugar, which isn’t recommended.

“Cleansing” can mean a whole lot of things but some problems with it are discussed here. Coffee enemas have no proven benefits and may cause colitis, an inflammation of the colon.

Paleo/keto: Some thoughts on the so-called ‘caveman’ diet. Some thoughts on keto diets. Diets are going to be highly personalized, based on a person’s individual health conditions and goals. But the bottom line here is that diets calling for a lot of meat consumption (especially red and processed meats) generally aren’t going to be healthy options in the long term.

Steaming your vagina is not recommended.

Charcoal has medical uses, such as to absorb toxins that someone may have ingested. Casually taking it? Not so much.

Clay has been used for a wide variety of ailments. More needs to be known about it, though, and it’s not advisable to eat clay.

Shooting up vitamins: In generally, it’s inadvisable to take supplement of vitamins or minerals in the absence of a specific diagnosis or deficiency. “Drip bar” or boutique IV drips aren’t FDA-approved.

Infrared light/sauna: Some kinds of light are used as therapy for certain skin conditions. I would consult a dermatologist about light exposure.

Naturopaths/shamans/functional practitioners: Same as with any professional. Is the person practicing a regulated field, and are their therapeutics scientifically tested for safety and efficacy? In other words, are they safe and are they shown to be not dangerous? If these questions cannot be answered, I would be skeptical. Same would go for Well + Good: who is writing the articles, and are they trying to sell you a bunch of stuff?

Telomeres do shorten with age, and you can read about it here.

You can read about Goop’s outrageous claims here.

Grace brings up some “controversial experiments on humans” conducted by Robert Galbraith Heath, an old-timey neurologist and psychiatrist who spent his career implanting electrodes into the brains of gay men in hopes of curing their homosexuality and using African Americans as test subjects because, according to one collaborator, “they were everywhere and cheap experimental animals.” While the medical profession has an ugly history of racism, homophobia, and unethical experimentation, this by itself does not disprove medical science or practice; this unfortunate history is rather evidence of the fallibility of humans and human institutions. ↩

Editor’s note: Jen Gunter, MD, has put together great tips for how to search for quality medical information online. ↩