In Defense of “Bad” Activism

Throwing soup on a painting may be a sub-optimal way of drawing attention to the climate crisis. But it’s an act of desperation from a generation being robbed of their future, and we should talk about the crisis instead of mocking the activists trying to stop it.

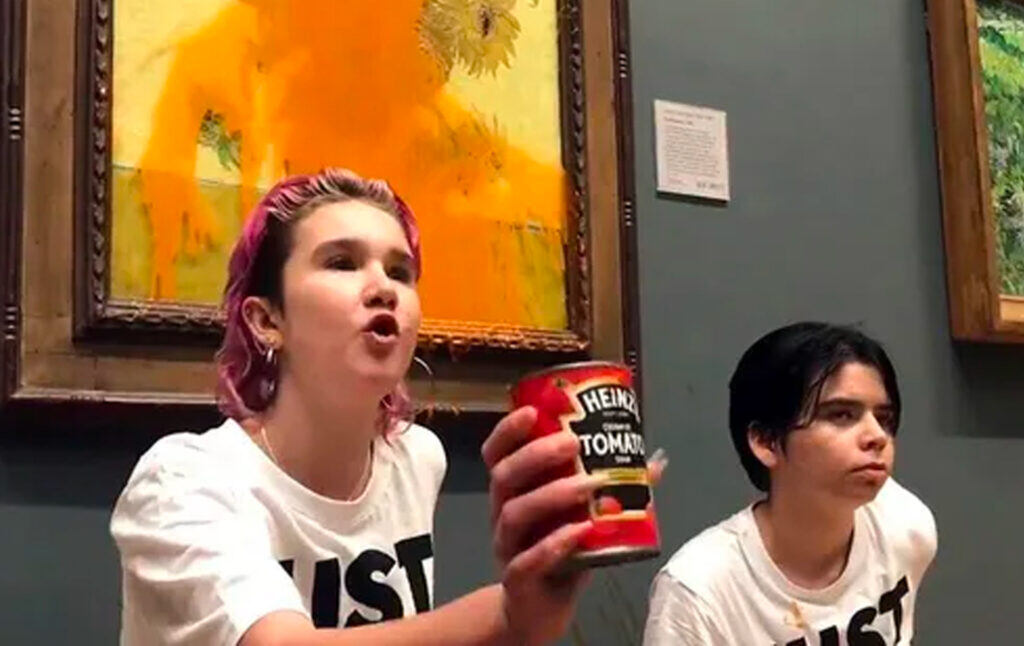

In London, a pair of very young-looking climate activists have been arrested for emptying a can of cream-of-tomato soup onto Vincent van Gogh’s “Sunflowers” painting at the National Gallery. They then glued themselves to the frame. The painting itself was unharmed (there was “minor damage to the frame”) but the activists, who were part of the group “Just Stop Oil,” were widely mocked on social media. “You did it, guys. You saved the earth,” said Ben Shapiro. A random sample of other reactions:

- I’m struggling to understand why destroying a painting of sunflowers done by Van Gogh, [note: painting wasn’t destroyed] an impoverished man who was marginalised in his local community due to his mental illness, is the right target to make a statement about how awful the oil industry is.

- the fuck did van gogh do to hurt the climate

- The vandalism or destruction of art is always an authoritarian act. But more than that – it represents a repudiation of civilisation and the achievements of humanity.

- What on earth has Van Gogh’s Sunflowers got to do with oil? Why not shove Michelangelo’s David into the sea to stop oil? Pound a mammoth skeleton into dust to stop oil? Stab a dolphin? Piss onto a puffin?

- I’m completely behind stopping oil, but this seems mad.

- Attacking #vangogh’s #Sunflowers? I support their advocacy for #ClimateAction but this was rather silly and senseless…. How will you garner support like this?

The stunt was the latest in a series, and apparently “climate protesters across Europe have for months been gluing themselves to the frames of famous paintings.” The Just Stop Oil activists asked onlookers which was more valuable, “art” or “life,” and gave a speech about the cost of living crisis and the destructive effects of fossil fuel use. For context, the U.K. government has recently lifted its ban on fracking and the Conservative climate minister has justified awarding more than 100 licenses for North Sea drilling, saying that fracking and oil drilling are “good for the environment.” (This madness didn’t, of course, get nearly as much attention as the action of the activists.)

Making fun of the activists is the easiest response in the world. I think their choice of tactics didn’t really make much sense. It brings media coverage, sure, but mostly of the “look how silly these activists are” variety, which is not what you’re aiming for. Does it build public support for the movement to end fossil fuel use? Doubtful.

And yet, it’s also important to understand where these young people are coming from. I’d note in their defense that people in their generation are desperate and anxious, because they see their future being stolen from them. They see the climate crisis getting worse, and they are ruled over by an unelected Prime Minister who believes in unfettered free market capitalism. In recent years, the efforts of young left activists in the Labour Party to introduce transformative progressive leadership were undemocratically thwarted by centrists within the party. These climate activists are coming from a place of extreme frustration with the burdens that they know they are going to face in the coming decades. Futile acts like this are the result of a sense of powerlessness.

Some activism is conducted by savvy strategic thinkers who have carefully weighed up the anticipated effect of their actions on public opinion in pursuit of a clear policy goal. But sometimes activism is a cry of anger by those who do not know what else to do except to somehow “throw their body on the gears.” The London activists weren’t the first to deface paintings in the service of a noble cause. The Suffragettes did the same thing. In 1914, Mary Richardson of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) hacked up a Velázquez painting in the National Gallery using a meat cleaver. She was protesting against the jailing of WSPU founder Emmeline Pankhurst.

Now, in that case there was a bit more of a connection between the subject of the painting and the cause. The painting depicted Venus, and Richardson said:

“I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history as a protest against the Government for destroying Mrs Pankhurst, who is the most beautiful character in modern history. Justice is an element of beauty as much as colour and outline on canvas.”

Did this help Pankhurst? Probably not. But I’m sympathetic to Richardson. People do things like this because an injustice is being committed and there doesn’t seem any obvious way to stop it. It’s also a reason why I take issue with those who make points like “rioting in the wake of police brutality incidents isn’t an effective protest tactic” as a way of condemning rioters. Correct, they’re not effective. I wouldn’t advocate a riot if you’re trying to bring about policy change. But when Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke of riots as the “language of the unheard,” this was a very profound phrase. These kinds of actions are the result of a failed political process that isn’t responding to people’s legitimate grievances.1

The history of activism is riddled with examples of counterproductive tactics. I think a lot of stuff the Yippies did during the ‘60s wasn’t that useful. The Weathermen were even worse. But the Weathermen were driven to their violence by their rage at the atrocity of the Vietnam war and frustration at their inability to do anything about it. I am completely in sympathy with the animal welfare movement, but plenty of animal welfare activists have done cringeworthy and counterproductive actions that contribute to people thinking of the movement as kooky and self-righteous.

Do I wish they’d be more strategic? Yeah, I do, and I’ve written critically of, for example Antifa when they use tactics (like hitting people) that I think end up generating sympathy for the right. Participants in movements should absolutely ask themselves questions like: is blocking traffic just going to get motorists mad at us without changing any minds? They should study the history of social movements to figure out what works, and be ruthlessly focused on achieving their goals rather than just making a point.

But I’m also not going to deride idealistic young people who are risking their freedom to do something about a cause that is incredibly important. And I think instead of treating these activists as the insane ones, we should see it as far more insane to allow the fossil fuel industry to destroy our future to maintain its profits. Why make fun of them when the industry’s actions are far more appropriately described as “lunacy” and global warming will result in the destruction of many, many more paintings? When the protesters demand to know whether we prefer “art” or “life,” they are asking a valid question: what do we value? Why is it that the desecration (temporary, harmless) of a painting excites more outrage than the despoliation of the entire planet and all its wonders? Why ask what’s wrong with them rather than asking what’s wrong with everyone else? Is not climate change act of vandalism (and ultimately, theft and murder) far, far worse than the spilling of the soup? If we are sane, should we not discuss the thing they were protesting about rather than the protest itself?

There is also an argument to be made that even if the action made people upset, it ultimately will work, because it will start critical conversations in a way that less controversial actions would not. The soup protest is the first time I heard about Just Stop Oil, and now I know that they do a lot of valuable work that’s worth supporting. India Bourke of the New Statesman argues that the protest was (1) harmless (2) raised the profile of the climate crisis and gave a sense of the urgency and (3) would probably have been appreciated by van Gogh himself. I think it’s certainly possible that the action will turn out to have been more effective than it might seem and shouldn’t immediately be written off as bizarre and useless. Perhaps the only thing that will work is invading elite institutions and fucking up some paintings!

There’s an awful lot that’s cringeworthy about social justice politics, especially as practiced by 20-year-olds. But I did some ill-conceived activism when I was in college, too. (I didn’t throw soup on anything, though, as far as I remember.) They’re not sure what to do, because it’s hard to know what to do. And I sympathize completely. They care about something that matters. Perhaps their approach isn’t that well-thought out. But what are you doing? Are you risking your freedom for a morally important cause? And what do you think they should be doing instead? People are trying what they can. When a scientist chains themselves to a bank, does that “work”? I don’t know. They’re experimenting. They’re trying to figure out how they can wake people up, and it’s not easy.

Activists often make us uncomfortable. Lots of people just want to go on with their day and not have to think about horrible things like the climate catastrophe, and activists are doing their best to make sure we can’t stay oblivious. I’m far more sympathetic to those idealists who are trying to do something about the worst problems in the world than to people like Ben Shapiro who spend their entire lives downplaying those problems and doing nothing constructive for anyone. I don’t have to agree with the protesters’ choice of tactics to respect their commitment and values, and I would encourage those who are critical of them to think of better ways to motivate political action on the climate crisis and then take action.

In fact, historian Elizabeth Hinton argues in America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s that riots against police violence are better understood as acts of political rebellion—as part of a “sustained insurgency” against the state’s failure to enact policies around education, jobs, and social services and its reliance on law enforcement to police poor communities of color. She documents hundreds of rebellions since the 1960s, often in response to police violence, and situates the George Floyd uprisings of 2020 as part of this tradition. The implication is that those in power aren’t listening, not so much that the acts are ineffective. The 2020 uprisings, after all, have moved the conversation around prison abolition forward even as the two parties maintain their law and order politics. ↩