Cori Bush and the Path to Democratic Popularity

Democrats are failing to convince voters that the party cares about the most pressing issues facing the country. But some, like Rep. Cori Bush, are modeling what a compassionate and appealing Democratic Party might look like.

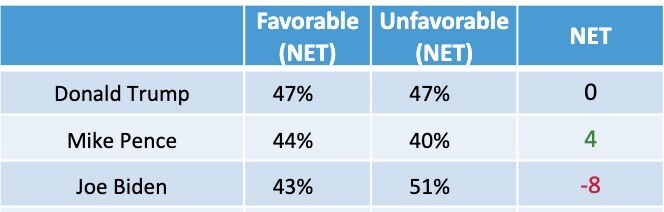

There is bad news for the Democratic Party: recent polling by the New York Times indicates that “49 percent of likely voters said they planned to vote for a Republican to represent them in Congress on Nov. 8, compared with 45 percent who planned to vote for a Democrat.” The bump that Democrats got after the Supreme Court eliminated the constitutional right to an abortion appears to have been wiped out, as inflation persists and economic issues are foremost in voters’ minds. The monthly Harvard/Harris poll for October contains some more alarming statistics: only about 1 in 4 Americans say the economy is on the “right track.” Fifty-seven percent of Americans say their personal financial situation is “getting worse,” compared with 22 percent in February of 2021, the month after Joe Biden first took office. Donald Trump and Mike Pence are now more popular than Joe Biden:

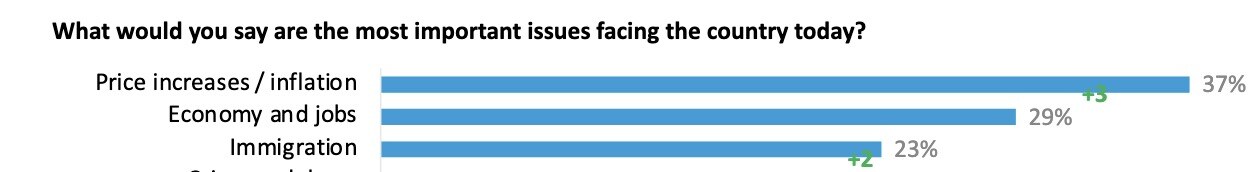

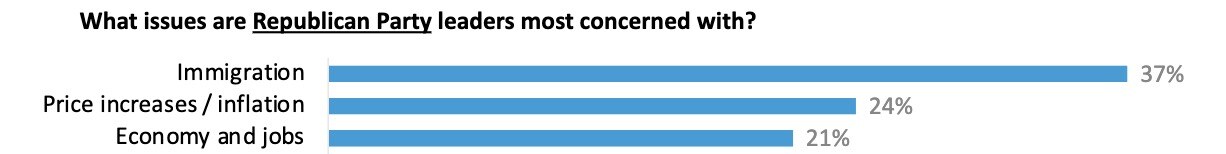

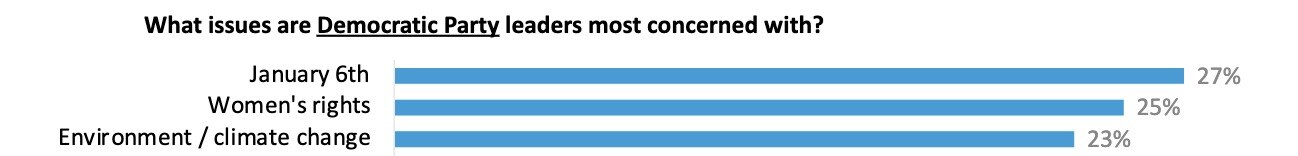

The poll’s most alarming finding is that voters think the Republican Party is focused on the issues that matter most. The top three issues that voters say are important are “price increases/inflation,” “economy and jobs,” and “immigration.” These are also the issues voters think Republicans are focused on, whereas voters think Democrats are focused on “Jan 6th,” “women’s rights,” and “environment/climate change”:

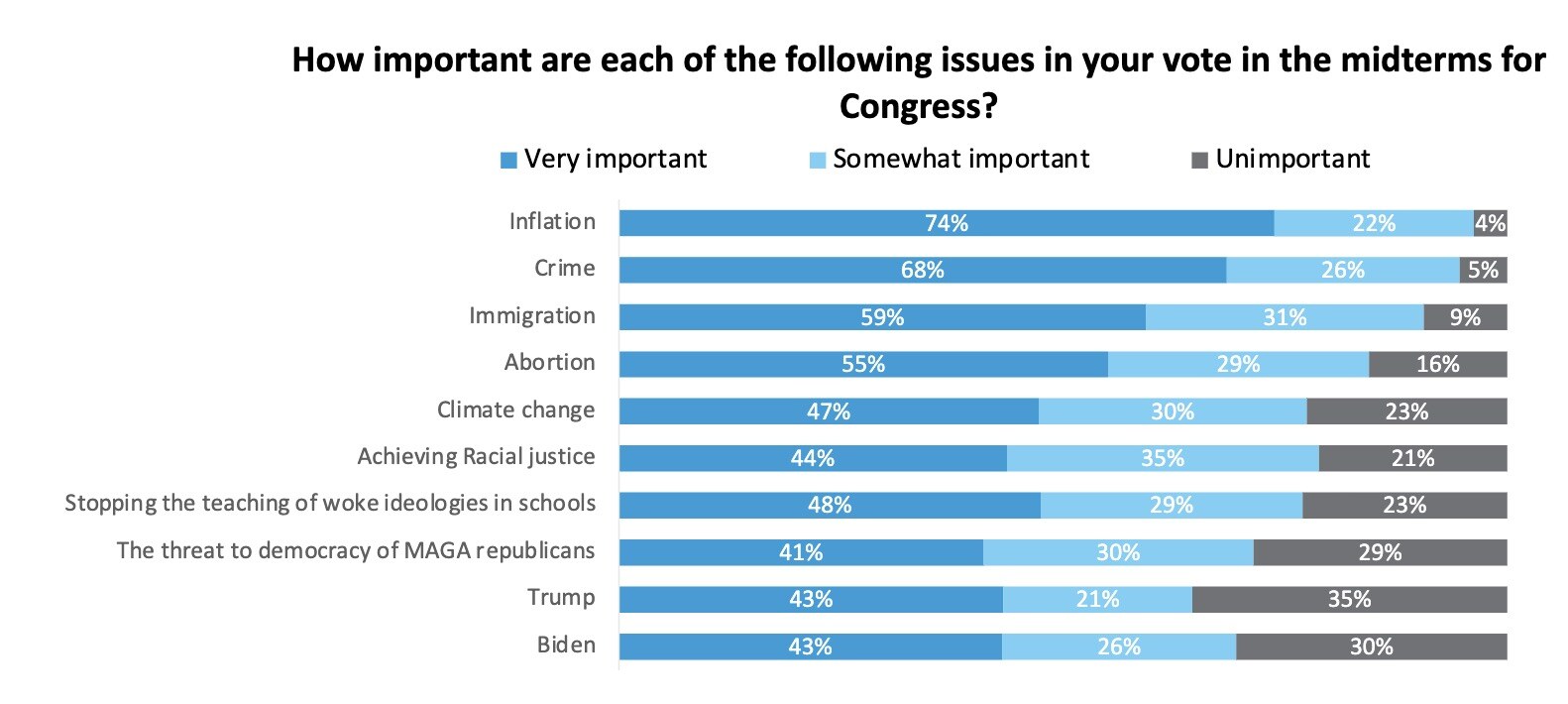

Other poll questions similarly find that more voters are concerned with the issues that Republicans tend to talk about (inflation, crime, immigration) than the issues Democrats tend to talk about (abortion, climate change, racial justice):

Now, these results have to be interpreted carefully. After all, just because voters are “concerned with the economy and jobs” does not mean they accept Republican Party solutions on the economy. (We’ve just seen in Britain how a right-wing government has tanked its popularity through a program of tax cuts for the rich.) But I do think there is confirmation here of what some of us have been saying for a while, which is that the obsessive Democratic focus on January 6 has not been a good idea. There was a deliberate effort on the part of party leaders to put January 6 at the forefront of voters’ minds, and while that effort has succeeded in making voters think the party cares a lot about January 6, it has not succeeded in making them think the party is in touch with everyday people’s most pressing concerns. And while Congress passed an “Inflation Reduction Act,” inflation has not actually been reduced, and everyone knows this.

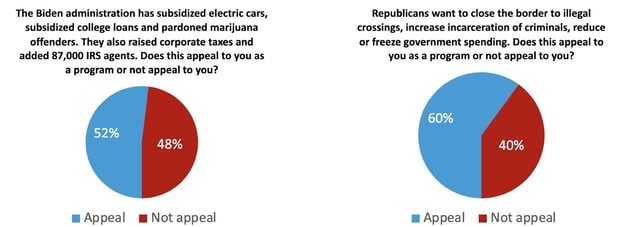

The Harvard-Harris poll can be criticized over some of the ways it frames its questions. For instance, it asks questions like “Do you think the rise in crime is the fault of woke politicians or other factors?” and then reports that most Americans reply “woke politicians.” This is a leading question that doesn’t give people other plausible answers, and I’d be far more interested to see the range of responses if you asked people the open-ended question, “What factors do you think cause crime?” I suspect “woke politicians” would not be the answer written by 64 percent of people, as it is in the Harvard-Harris poll. The poll also asks other clearly-biased questions like, “Do you think it was right or wrong for President Biden to spend over $400 billion on student loan forgiveness without authorization by Congress?” (No mention of the suffering relieved by loan forgiveness, and makes the controversial assumption that Biden lacked authorization) and “Do we need to emphasize lower gasoline prices and energy independence or higher gasoline prices and climate change?” (what a stupid question). The poll’s framing of the Biden administration’s priorities and Republicans’ priorities is also misleading, including the “87,000 IRS agents” Republican talking point:

We know that it’s very easy to get the survey results you want by manipulating people through the questions you ask. Medicare for All is extremely popular when you describe it accurately, but if you wrongly imply it will leave people uninsured (by saying it will “take away their private health insurance”) it becomes less popular, and opponents of Medicare for All use the misleading survey answers to argue that M4A is less popular than it seems. So let’s not conclude from the Harvard-Harris poll that American voters want Republican policies and that Democrats need to “run to the center” and start getting “tough” on crime and immigrants. (Even though “immigration” is listed as an issue of top concern, for instance, the number of people who want new immigration restrictions has dropped massively over the last two decades, while the number of people who welcome more immigrants is steadily increasing.)

But what we can tell from the available data is that Democrats are not effectively countering Republican messaging on the economy. The Republican stance on abortion rights is not popular, but if people can’t afford their grocery bills, they may be receptive to the Right’s message that Democrats aren’t doing anything to lower your bills. I am not sure that Democrats are going to get completely wiped out in the midterms—there are, after all, some absolutely horrible candidates running on the Republican side, especially in Senate races. But Donald Trump’s 2016 election showed that when times are tough and people are angry, the fact that a Republican is incompetent and morally loathsome does not mean they are guaranteed to lose.

There are signs of what a different, better Democratic Party could look like, however. Rep. Cori Bush has just released her memoir, The Forerunner, and I’d recommend that anyone pick it up who is interested in seeing what effective working-class progressive politics looks like. Bush gets less attention than her fellow Squad and DSA member Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, but her personal story is just as remarkable, and I think if we want to see how Democrats can effectively connect to working people, Bush’s message is a very useful model.

The Forerunner shows that Cori Bush had a long, tough journey to Congress. She was born into a middle-class Black family in a St. Louis suburb, and her parents were loving and supportive. But from a young age, Bush was ensnared in violent relationships with men. The stories of her abuse are horrifying and graphic. Bush was choked, punched, and cut with box cutters. One boyfriend, who insisted on keeping a gun in the bed with them, told her he would murder her father if she ever left him, and when she finally escaped he chased her, shooting at her. She was raped multiple times. One boyfriend gathered all of her possessions and set fire to them. Bush explains how partners would alternate between extreme brutal violence and being “loving and repentant,” trapping her in the familiar cycle of abuse and making her feel it was impossible to leave.

Bush knows what it is like to be a working-class single mom. She has lived out of a car with two children, keeping her clothes in a trash bag in the back seat and using a McDonald’s bathroom to clean up for work. She tells how she would turn the car off and on all night, trying to keep warm without using too much gas, and getting only a few hours’ intermittent sleep. She spent ten years working at a preschool, barely able to afford her rent, and dealing with multiple evictions. To avoid utility shutoffs, she had to resort to payday loans that have been nearly impossible to pay off.

Bush ultimately became a nurse, and saw first-hand the inequities in the American healthcare system. She had herself experienced racist and neglectful care in hospitals, as she watched her prematurely-born son struggle to live during four months in the NICU. As a nurse, she saw Black patients receive inferior treatment, and was anguished when she couldn’t help people with the underlying conditions fueling their health problems. Bush’s observations made her determined to do something more to help:

“If a child’s Medicaid had lapsed, and a parent couldn’t afford their ADHD medication, for example, the child would not be welcomed back to school. Often, parents couldn’t pay out of pocket. Medicaid might determine that the child was too young for a particular controlled drug, like medication for depression or anxiety. Either the child would not receive his medication, or it could take months of documentation on our part to receive approval, during which time the child would be unable to attend school.

Every day, I witnessed how pharmaceutical companies make being poor so expensive. Our access to money determines our ability to get the prescriptions we need, and it’s not right. Why should American families have to choose between putting food on the table and getting their children the treatment they need? This is why today I advocate for Medicaid expansion and Medicare For All. At the clinic, I got to learn firsthand that our system is broken.”

Though Bush has experienced alcoholism, homelessness, and abuse, The Forerunner does not relate the stories in order to tell others in similar situations they should exercise Personal Responsibility so that they, too, can end up in Congress. Instead, Bush is determined that others shouldn’t have to go through the same things that she did. In her majority-white high school, Bush was made to feel like a “nobody with nothing to contribute,” and she doesn’t want other Black girls to feel the same. Reflecting on her time as a preschool worker, she says that “no one who is educating children should go to work worried that her electricity is going to be cut off at home.” “I wish my young adulthood and my children’s early years could have taken place in a different America, a better America.” When she was at the payday loan office, she thought to herself, “Why do I have to come here and do this again? Where can single parents get real help? What are our elected officials doing to help ease our load?”

Even though Bush suffered horrendous abuse at the hands of her partners, she even writes sympathetically of their backgrounds. Bush notes that, unlike her, these men came from families where love was in short supply. One boyfriend had a father who died in prison, and a mother who dealt with drug dependency. Bush at one point refused to testify against her partner even after he tried to kill her, because she “couldn’t stand the thought of being the reason that someone went to prison.”

Bush’s experience as a survivor of violent crime means she is uniquely positioned to advance a nuanced message on policing and criminal punishment. Bush came to public prominence as an activist in the Ferguson protests, demanding accountability for the death of Michael Brown. She emphasizes the injustice that Black communities suffer at the hands of police, and she herself was sexually harassed by a police officer as a young girl. But nobody can say that Bush doesn’t care about crime victims. She recounts movingly the story of an ex-boyfriend who was murdered the night he was supposed to meet up with her, and names half a dozen friends from childhood who died violent deaths.

The problem, for Bush, is that too often the institutions that are supposed to protect people end up hurting them more. Her abusive boyfriend’s incarcerated parents “had needed help, an advocate, or humane policy—not prison.” Bush also relates how the church, another institution that should provide safety and love, let her down repeatedly. Married pastors would sexually harass her, and at one point she ran, bloodied and bruised, to the entrance of the church to escape her pursuing boyfriend, only to have church staff literally lock the doors so she couldn’t get in.

Bush herself became a pastor, and is deeply religious. What she wants for others is the kind of compassion that, at too many points in her life, she did not receive. The stories she tells may sometimes even make progressives uncomfortable. At one point, she discusses how the staff at an abortion clinic pressured her to go through with an abortion even as she protested that she had changed her mind. She thinks supporters of abortion rights might “be outraged by my decision to share this story,” and “antichoice activists will not doubt use my traumatic experience to try to strip abortion providers of their ability to serve our communities.” But her point is that rights aren’t enough. We also need everyone to receive empathetic care, of the kind she rarely found in the U.S. healthcare system. “No one should have to live through prenatal, birth, and postpartum experiences like the ones I endured,” Bush says.

Bush recounts how she found the kind of politics that represented her when she heard Bernie Sanders speak. She had been disappointed with Barack Obama for shunning Ferguson activists, and was disgusted when Hillary Clinton’s message was “all lives matter.” But at a Bernie event, Bush “noticed that he was speaking frankly about the connection between racial justice and income inequality, and I heard him name mass movements as a solution.” Bernie, she said, was willing to demand we “demilitarize the police,” while “every single other candidate refused to acknowledge the particular precarity we face in this country as Black people.” She “felt vindicated and validated. Here was this older white presidential candidate telling a Black room that Black lives matter. … He’d shown me that I didn’t have to temper what I believed.” Bush writes that she wanted to “disrupt the facile narrative that Senator Sanders’s support was made up almost entirely of so-called Bernie Bros, deemed aggressive white men who lacked a serious awareness of racial or gender politics,” and when she campaigned for him she was “happy to talk about how Bernie supported us when other politicians with aspirations to higher office refused to.” For Bush, the Bernie agenda was an agenda that dealt specifically with the needs of her community:

“To me, Black people need quality health care and education, free college tuition, and student loan debt forgiveness. We need a living wage, safe and affordable housing, reliable public transportation, environmental justice, broadband access, economic equity capital, and an end to mass incarceration and police violence. This was not a white liberal agenda to me. It is an agenda that saves lives.”

Bush ran unsuccessfully for office twice before being elected to the House of Representatives in 2020. She is proud that her run shows that “a regular, everyday person [can] do what others deal impossible,” and sees her election as a victory that should inspire “victims and survivors of assault, low-wage workers, single parents, people living with disabilities, folks who are unhoused or transient, people on EBT, WIC, or any other form of state assistance, people with credit issues, those who are incarcerated or were formerly incarcerated, those who are LGBTQIA+, and members of every marginalized group.”

Bush has been a combative member of Congress, being willing to do battle with the Biden administration and use confrontational protest tactics in the service of preventing evictions. Bush certainly found the January 6 riot outrageous, calling for Republicans who supported it to be expelled from Congress. But in her public statements and her memoir, Bush emphasizes again and again the simple message that Americans suffer too many preventable hardships and that it is the job of elected officials to care about them and to try to make things different. Her campaign victory speech, reprinted at the end of The Forerunner, has an uncommonly earnest profession that she loves the people she serves:

I was that person running for my life across a parking lot, running from an abuser. I remember hearing bullets whizz past my head and at that moment I wondered: “How do I make it out of this life?” I was uninsured. I’ve been that uninsured person… hoping my healthcare provider wouldn’t embarrass me by asking me if I had insurance. I wondered: “How will I bear this?” I was a single parent. I’ve been that single parent struggling paycheck to paycheck, sitting outside the payday loan office, wondering “how much more will I have to sacrifice?” I was that COVID-19 patient. I’ve been that COVID-19 patient gasping for breath, wondering, “how long will it be until I can breathe freely again.

My message today is to every Black, Brown, immigrant, queer, and trans person, and to every person locked out of opportunities to thrive because of oppressive systems: I’m here to serve you. To every person who knows what it’s like to give a loved one that ‘just make it home safely baby’ talk; I love you. To every parent facing a choice between putting food on the table and keeping a roof over their head; I’m here to serve you. To every precious child in our failing foster system; I love you. To every teacher doing the impossible to teach through this pandemic; I love you. To every student struggling to the finish line: I love you. To every person living with disabilities denied equal access: I love you. To every person living unhoused on the streets: I love you. To every family that’s lost loved ones to gun violence: I love you. To every person who’s lost a job, or a home, or healthcare, or hope: I love you.

[…] Your Congresswoman-elect loves you. And I need you to get that. Because if I love you, I care that you eat. If I love you, I care that you have shelter, and adequate, safe housing. If I love you, I care that you have clean water and clean air and you have a liveable wage. If I love you, I care that the police don’t murder you. If I love you, I care that you make it home safely. If I love you, I care that you are able to have a dignity and have a quality of life the same as the next person, the same as those that don’t look like you, that didn’t grow up the way you did, those that don’t have the same socioeconomic status as you. I care.

And so regardless of whatever was, this is our moment and this is our time and that’s how it will be. So when you walk away from here, you walk with your chest poked out that change has come to this district … we are going to love and respect and honor one another to change the face of this district and become who we know we can be to have a safe, loving, welcoming, and thriving community.”

I am not sure how many politicians other than Bush could be effective using the word “love” this way. I’m not saying that the Democratic Party needs to embrace the Marianne Williamson agenda of “a politics of love,” although there’s a lot to like about it. But I do think Cori Bush sounds honest and compassionate in a way that Democrats will need to if they are to reverse the worrisome trends in the polls cited above. Voters need to be convinced that their elected representatives have the public interest at heart, and Cori Bush has shown how that can be done. She doesn’t pretend to be what she isn’t. She shows her humanity and links her life experiences clearly to her agenda. Let us hope she is indeed the forerunner of a new kind of progressive politics.