U.S. Empire and the Marvel Moral Universe

Comic book stories shape and reaffirm cultural and political attitudes. We shouldn’t settle for the imperialist propaganda put out by the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

I remember very vividly the first time I watched Iron Man 2. It was the middle of the summer, and a friend of mine had invited a group to watch the movie, which must have just been released on DVD, at his house as a part of a celebration of his twelfth birthday. Eager for cartoonish violence in the manner stereotypical of boys of that age, we loved the film for its fast-paced plot and numerous action scenes, but the part that excited us most was the briefest glimpse of the famous shield of Captain America, which Tony Stark/Iron Man uses to jury-rig a machine he is building. We were still a year away from that famous hero’s true silver screen debut in Captain America: The First Avenger, but the promise of his eventual appearance was enough to rile a gaggle of kids already hopped up on popcorn and soda.

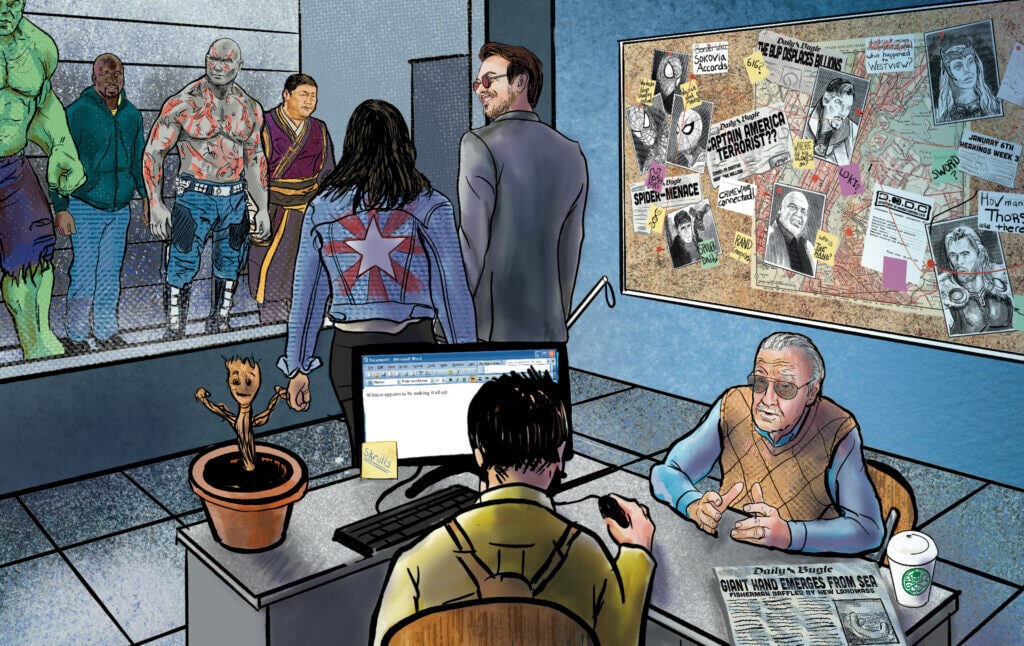

Nearly 12 years later, it’s impossible to watch that part of the movie without seeing it as anything but a glorified commercial for Marvel’s upcoming creative ventures. The scene was an augur of the model that has both made the studio’s films unique and seemingly condemned them to a superficial model of eternal self-referentiality. Now, the very word “Marvel” conjures up notions of grand scale superhero stories, none of which seem to be watchable anymore without knowing what else has happened in any of the dozens of preceding releases (good luck following the newest Doctor Strange without watching WandaVision on the subscription-based streaming service Disney+). At this point, you might be fully on board, caught up with the latest entangled installments of the ever-evolving tale of enhanced beings fighting enemies wherever they may be found. Or you’re fully lost, left out of the studio’s business model of cinematic dominance that ensures that your local theater, even if it’s no longer playing Drive My Car, has dozens of daily showtimes for Doctor Strange and The Multiverse of Madness.

Since the creation of the Marvel Cinematic Universe in 2008 and its subsequent acquisition by Disney in 2009, Marvel has perfected a business model predicated upon the continual release of largely formulaic action films. These films, primarily drawing their emotional weight from nostalgia and self-reference, tend to lack artistic and moral complexity and creative risk—and reflect a political ethos that is attuned to liberal-woke sensibilities but nonetheless glorifies imperialism. The same way ancient Athenian theater reinforced civic ideals of democracy, justice, and honor using the heroes and deities from Hellenic mythology, the Marvel Cinematic Universe draws on the mythology of American comic books to reinforce our culture’s dominant ideals, those of perpetual conflict against perpetual enemies in a world order characterized by American military and political hegemony. The films hardly make any effort to justify these ideals, much less critically interrogate them. The movies’ characters do at times use certain leftist critiques, such as the language of class antagonism or the concern about wealth and power being abused by individuals. But these critiques end up neutralized in favor of the status quo.

Comic books and their heroes have had a rich and contradictory history in U.S. culture. Paul S. Hirsch has tracked their history in his thorough and incisive (not to mention well-illustrated) book Pulp Empire: The Secret History of Comic Book Imperialism. Hirsch shows that American attitudes toward comic books have evolved. First the books were seen as harmless pulp, then as a scandalous danger in need of censoring (a series of Congressional hearings in the mid-1950s linked the content and popularity of comic books to an apparent increase in juvenile delinquency), before their eventual appropriation by the American security state for use, at least in part, as imperial propaganda. In his introduction, Hirsch writes:

“Marvel’s new heroes [in the 1960s] straddled the line between purely commercial comic books and propaganda titles. These characters and narratives supported the Cold War consensus, a domestic coalition that crossed party lines and embraced the exertion of American power around the world and confrontations with Communism wherever it surfaced. By the early 1960s, comic book superheroes were waging war against the communists in Vietnam. Armed with the fruits of American technological prowess and wealth, Iron Man fought a one-man war against Soviet-style totalitarianism. Thor also went to Vietnam, where he used his godly powers to halt a North Vietnamese sneak attack.”

Surprisingly, many of these comics were not even created under input from federal officials, originating instead as workarounds for censorship codes that emerged after the aforementioned Congressional hearing, and for the general Cold War panic that pervaded American culture at the time.

Popular comic book heroes first made the jump from the page to the silver screen in film serials throughout the 1940s. Though commercially successful at the time, these serials didn’t survive the decline of the Saturday matinee format alongside the rise of television. The first big-budget superhero film that might be said to resemble the kind we watch today was Richard Donner’s 1978 film Superman, with Christopher Reeve in the starring role. Eleven years later came Tim Burton’s similarly well-received Batman. Both critically and commercially successful, each film spawned franchises that petered out after the dwindling reception of the later sequels. Furthermore, the success of Batman and Superman wasn’t part of a trend. Despite the popularity of these flagship DC comics characters, the popularity of their films remained more the exception than the rule for comic book movies. Marvel, while home to other iconic superhero teams like the Avengers and the Fantastic Four, did not achieve the same success as its DC counterparts, most of their releases appearing only on television or being released directly to home video.

This changed in the late ‘90s and early aughts with the appearance of Blade in 1998, then X-Men in 2000. Both of these films and their subsequent sequels were early indicators of the potential for superheroes to generate not only mass cultural appeal but also handsome box office returns: X-Men brought in nearly $300 million on a $75 million budget, and its sequels did even better, most of them raking in more than $400 million each. Chris Hewitt of Empire has written that X–Men was “the catalyst for everything that’s come since, good and bad. Without it, there’s no Marvel Studios,” the production group that later blossomed out of the comic company’s desire to make their own movies, instead of merely licensing out their intellectual properties to other film studios.

Hot on the heels of the success of Blade and X-Men, various studios continued to make films by licensing the rights to different Marvel properties throughout the early 2000s with varying results, from the critical acclaim of Spider-Man 2 to the near universal panning of films like Daredevil and Elektra. This model shifted when producer and businessman David Maisel approached the then small Marvel Studios about earning more money for their films. Instead of simply licensing out their intellectual properties for other film studios to adapt, Marvel could, Maisel proposed, make their own films using characters whose rights they hadn’t yet sold, including many of the original members of the Avengers, Marvel’s analogue of DC Comics’ Justice League and perhaps its most recognizable property. Instead of just aiming to make a slew of independent stories, however, the budding film studio decided to set their films within the same fictional continuity, laying the groundwork for a media empire built on the potential for different heroes to appear in each other’s films as part of a shared universe known as the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU). For such an approach to succeed, however, the studio would have to kick it off with a bang. The first on the docket: Iron Man, released in 2008.

Perhaps no superhero looms larger in our current cultural consciousness than arms magnate turned superhero Iron Man, even after his onscreen death in 2019’s Avengers: Endgame. Despite his fictional backstory as a founding member of the Avengers, Tony Stark (and his mech-suit alter ego) was until recently considered a relatively minor superhero, lacking the name recognition of a hero like Spider-Man or Thor. In the end, it didn’t matter: Jon Favreau’s Iron Man was released to near universal positive acclaim from critics and fans alike, particularly for Robert Downey, Jr.’s performance in the titular role (the late Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times wrote, “At the end of the day it’s Robert Downey, Jr. who powers the lift-off separating this from most other superhero movies.”) Furthermore, the first utterance of the word “Avenger” in a post-credits scene promised the movie to be the first chapter in an interconnected saga that would unite so many beloved superheroes on the same screen. The film was so successful that the fine folks over at Disney must have foreseen an oncoming boom on which they could cash in. At the end of 2009, the media conglomerate acquired Marvel Studios for $4 billion. Disney’s investment has paid off: nearly 14 years after 2008’s Iron Man, the 28 films of the MCU have grossed more than $26 billion worldwide.

You wouldn’t necessarily know it from the way the movies have evolved, but the first Iron Man film gestures at a critique of the American military-industrial complex. After a weapons demonstration in Afghanistan, arms magnate Tony Stark is captured by the terrorist organization the Ten Rings, who show him the destruction his handiwork has helped wreak when they try to force him to build the same advanced missiles he builds for the U.S. Air Force. Instead, he builds the Iron Man suit, which he uses to escape captivity before returning stateside and shutting down his company’s weapons sales. He takes on the Iron Man mantle in his solo efforts to defeat his former business partner Obadiah Stane, who builds his own mech-suit to kill Tony so that the company’s war profiteering can continue undisturbed.

Tony Stark’s character may selectively excoriate war profiteering, but the film ignores any real structural critique of American imperialism. Released at a moment of growing popular dissatisfaction with America’s endless military adventuring in the Middle East, Iron Man bemoans the loss of the lives of American soldiers, yet it fails to make any broader or more incisive interrogations of U.S. military presence in Afghanistan, or of the broader apparatus of the American war machine. Instead of asking why the Ten Rings, a clear stand-in for the Taliban or Al-Qaeda, might want to expel the American military, the film treats terrorists as faceless enemies with opaque and static motives. The film treats their wickedness as second only to that of Obadiah Stane, who commits the cardinal sin not of selling arms, but of selling them to people the U.S. Air Force doesn’t like. Instead of channeling his newly discovered morality into a critical re-examination of war and geopolitics, Stark channels it into the creation of his own superweapon, one that only he, an arrogant, unaccountable billionaire, is allowed to use.

While the first film at least nods toward critique, Iron Man 2 abandons the anti-imperialist pretense altogether, painting as ludicrous the attempts of the U.S. Congress—a legislative body not exactly known for its checks on American warmaking—to commandeer the Iron Man suit. “I’ve successfully privatized world peace,” says Stark, unironically showing us that a billionaire will always act like a billionaire, no matter how much of a conscience they seem to have grown.

But Iron Man is just one hero. If Marvel and Disney were going to make a media empire, they would need a couple other larger-than-life characters to balance him out to ensure audiences’ emotional and financial buy-in to the franchise’s storytelling choices—and simply to keep them from getting bored. They found one such foil in Steve Rogers, better known as Captain America.

Captain America: The First Avenger, released in 2011 to further acclaim, is a fun escapist romp, a kind of alternate history wherein science fiction and fantasy elements buttress the historical narrative of the fight against Hitler’s genocidal fascism. As expected for a film set in World War II, the movie relies heavily on our collective cultural nostalgia for the last war our country waged that could be considered justified. Furthermore, Steve Rogers is the perfect complement to Tony Stark. Whereas Iron Man was a minor comic book character until he found success on the silver screen in 2008, Captain America has been a household name since his first appearance as Nazi-bashing superhero on the eve of World War II. While Tony Stark is the perpetual winner whose recently discovered morality gives him carte blanche to wage war with impunity, Steve Rogers is a scrappy underdog, a sickly kid from Brooklyn who becomes Captain America not just because of an experimental serum, but also through his selflessness—not to mention unbridled patriotism. His primary villain is not the faceless Arabs of the Middle East or their greedy American benefactor, but the Red Skull, Hitler’s fictional protégé. You couldn’t ask for a more all-American hero.

Though the politics of the first Captain America film are themselves neither particularly egregious nor sophisticated, the movie serves to foreground one of the MCU’s most central assumptions: the ubiquity of adversarial and antagonistic forces. It doesn’t matter whether these adversaries are Nazis, terrorists foreign or domestic, enhanced beings with evil agendas or personal grudges, invading alien overlords, robots gone haywire, or even visitors from other dimensions. According to the logic of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, there are always bad guys, so we will always need the good guys, who are inexplicably always on our team, to keep them at bay. Individual enemies can be defeated, but new ones will always rise to take their place. It’s the same logic peddled by emperors, kings, fascists, and neocons alike, one that discourages critical reflection and reaffirms the same kind of tribalist exceptionalism that has defined American foreign policy since the end of World War II and the beginning of the Cold War.

Many of these enemies are simply villains of the classic comic book mold, characters like Ant-Man’s Yellow Jacket or Doctor Strange’s Dormammu who have little motivation other than to be bad guys, whether out of desire for money or some form of world domination. Villains like these may be less interesting than antiheroes like The Godfather’s Michael Corleone or The Sopranos’ Tony Soprano, who fall into their evil ways out of a complex mixture of innate and extrinsic forces, but the villainy of these Marvel characters remains simple enough as not to be worth questioning. These villains are hardly worth understanding, let alone sympathizing with. In this sense, much of the Marvel moral universe is built around the same worldview as the kind George W. Bush espoused in his famous “axis of evil” speech delivered in the months after 9/11, where America’s enemies were unquestionably malevolent but our own history of incessantly bombing the Middle East remained unmentioned.

While some evildoers simply crave power or chaos, the Marvel Cinematic Universe also makes villains out of people with reasonable grievances, who seem to turn to crime or wickedness less out of pure evil than out of a zealotry that has been circumstantially intensified. Unlike in the case of some of the movies’ more straightforward villains, the presence of these grievances actually does complicate the villains’ characterizations, but the films nonetheless condemn the wrongdoers, or else only pardon them after their defeat at the hands of the ever-righteous hero. Apparently, their violent tactics cancel out any complexity that might define their motivations. One example is Adrian Toomes/The Vulture of 2017’s Spider-Man: Homecoming. Originally of a working-class background, Toomes has made a fortune building and selling weapons made from stolen alien technology that has been otherwise hoarded by Tony Stark/Iron Man and the Avengers. Toomes’ exchange with Peter Parker/Spider-Man in the lead up to the film’s climax is particularly illustrative:

Toomes

Peter, you’re young. You don’t understand how the world works.

Parker

Yeah, but I understand that selling weapons to criminals is wrong.

Toomes

How do you think your buddy Stark paid for that tower? Or any of his little toys? Those people, Pete, those people up there, the rich and the powerful, they do whatever they want. Guys like us, you and me, they don’t care about us. We build their roads, we fight all their wars and everything, they don’t care about us. We have to pick up after them, we have to eat their table scraps. That’s how it is.

Here, Toomes sounds like a veritable class warrior, a Bernie Sanders in the making. Such language evoking class antagonism is notable given Americans’ distaste for the economic inequality of U.S. society. This year, Pew Research Center noted that a majority of Americans surveyed believe that the economy works for the rich and harms the poor and middle class; roughly half of those surveyed also believe the economy hurts their families. But unlike the more radical wing of the left, which would call for the expropriation of billionaires, Toomes does not seem interested in toppling the reigning order, as “that’s how it is.” Instead, Toomes is simply a villain who dares to steal from the almighty Avengers, while Stark, Peter Parker/Spider-Man’s in-movie mentor, remains a hero because of both his wealth and his connection to the Avengers and the American security and military state, whose insurmountable body counts go unmentioned. Thus, Toomes’ class analysis is ultimately neutralized.

Though released three years prior to George Floyd’s murder, Spider-Man: Homecoming also presages the logic deployed by mainstream cable news outlets toward rioters and looters in the summer of 2020, never mentioning the continuous “legalized looting” of the working class by our country’s elite, to use the words of Cornel West in an appearance on CNN in June 2020. Whereas the Avengers continue to operate, Toomes is defeated in a kind of proxy metaphor for the ongoing assault on the working class, the class war’s perpetual losers seemingly long resigned to their continual losses.

A more egregious villainization of an individual with legitimate grievances appears in the critically acclaimed 2018 film Black Panther, wherein Erik Killmonger, the film’s villain, attempts to initiate a global revolution for Black liberation by taking over and appropriating the resources of Wakanda, a fictional African nation noted for its hyper-development and profuse natural and technological resources. From a leftist perspective attuned to the crimes of imperialism and the myriad ways anti-Black racism manifests itself as an agent or remnant of colonial structures, Killmonger’s cause is hardly beyond reproach, as he attempts to appropriate Wakanda’s resources to advance a just and populist cause. Indeed, Killmonger is acting in service of the “wretched of the earth,” to pilfer a phrase from Frantz Fanon, the legendary anticolonial thinker who advocated for the necessity of violent revolution in shaking off the chains of colonial oppressors. If anything, Killmonger doesn’t take a solidaristic enough approach (such as that taken by some Third World leftists of the Global South who wished to unite against colonialism and imperialism in the mid-20th century), implicitly ignoring the plights of the poor and working classes of other races in his focus on the unique oppression that befalls Black people the world over. Through the film’s liberal imperialist lens, however, Killmonger is a wayward villain whom hero T’Challa, the young king of Wakanda who takes on the role of the Black Panther, needs to defeat. He even enlists the help of a CIA agent, suggestive of the numerous instances throughout the 20th century wherein agents of American imperialism crushed leftist governments or leftist resistance movements in the name of containing communism. Ultimately, Black Panther’s treatment of Killmonger reminds me of when a professor of mine once said, “The Israel-Palestine conflict is so difficult to solve because the Palestinians keep engaging in terrorism,” completely ignoring the conditions of violent oppression that might cause the oppressed to resort to violence of their own.

The 2021 television miniseries The Falcon and the Winter Soldier does perhaps slightly better justice to its primary villain Karli Morgenthau, whose pro-refugee, anti-border slogan “One world, one people” sounds like it could’ve been uttered by Leon Trotsky in his anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist advocacy of permanent international revolution. At the end of the series, Sam Wilson, a Black man who has newly assumed assumed the mantle of Captain America following Steve Rogers’ de facto retirement in 2019’s Avengers: Endgame, says, “You need to stop calling [Morgenthau and her followers] terrorists.” But this advocacy rings hollow coming from the avatar for American imperialism. To be fair, Wilson’s emotional struggle with taking up this mantle is a focal point of the series as he attempts to reckon with his country’s historical treatment of its Black super soldiers. His primary grievance arises upon his discovery that a Black super soldier named Isaiah Bradley was hidden from public and tortured by the United States government in lieu of recognition for his service in the Korean War. Wilson’s horror at the American empire’s treatment of its Black soldiers is justified but incomplete: the series rightfully acknowledges the brutality of this fictional injustice by giving Bradley a memorial in the Smithsonian in the final episode, but it doesn’t leave a word for, say, the hundreds of thousands of North Korean and Chinese soldiers and civilians who also died as casualties of America’s frequent and devastating bombings throughout the early 1950s.

Such is the myopia of Marvel’s attempted response to liberal calls for greater representation of people from marginalized communities in their films. Their approach mirrors that of the modern Democratic Party, which is content to place women and people of color in positions of power and influence but refuses to address the structural and historical causes that have contributed to those same groups’ historical marginalization. Just as the inclusion into politics of individual members of marginalized groups does not ensure radical, structural change, their representation in superhero films does not do justice to the conditions of their oppression when unaccompanied by a sufficiently complex characterization. It’s liberal imperialism at its most gripping and most refined, shown through the prism of sensational superhero movies that prioritize “inclusion in the atrocious” rather than any sort of radical critique of the institutions that commit and perpetuate such atrocities.

In the end, it’s not that the Marvel Cinematic Universe shallowly avoids grappling with the moral and political complexities of the conflicts it portrays. Instead, it chooses to tackle them, and yet nearly always comes down on the wrong side. Even in the Marvel movie with the best politics, 2014’s Captain America: The Winter Soldier, the implicit critique of the American surveillance state and Obama-era drone warfare is barely directed at S.H.I.E.L.D., the MCU’s analogue for the colossal apparatus that makes up the modern American security state. Instead, it’s all the fault of S.H.I.E.L.D.’s (neo-)Nazi counterpart Hydra, which has infiltrated the American agency, a sneaky way for the filmmakers to portray a domestic threat without actually critiquing the United States.

Nowhere is this tendency more evident than 2016’s Captain America: Civil War, which pits the MCU’s two golden boys, Captain America and Iron Man, against each other in a disagreement that even their camaraderie can’t handle. At the film’s beginning, the U.S. Secretary of State Thaddeus Ross urges the Avengers to submit themselves to the United Nations’ efforts to rein in the Avengers’ ability to operate with impunity, no matter the extent of the destruction the team wreaks across the world. Embodying the pattern of the MCU’s more or less uncritical depiction of so many of its heroes, Steve Rogers/Captain America balks at the notion of accountability, saying, “The safest hands are still our own.” Captain America’s words can be interpreted as an embodiment of U.S. military impunity at its most extreme, where it operates on the assumption of its continuous infallibility despite its abysmal track record of building democracy through military coercion, not to mention its long list of war crimes and its tendency to treat international law as an easily ignorable suggestion. Colonel James Rhodes/War Machine, a former Air Force pilot and another Avenger, justifiably describes Rogers’ attitude as “dangerously arrogant.” Considering the clear parallel to the UN’s continued and unheeded efforts to call out American war crimes, the applicability of this former soldier’s comments to U.S. foreign policy represents a textbook example of irony, one apparently lost on the filmmakers who seem to have more interest in reinforcing than subverting cultural norms. Instead, the film treats Rhodes as misguided and Rogers as in the right, because he’s Steve Rogers, leader of the Avengers, the Earth’s mightiest heroes and an unquestioned Force for Good. Captain America practically scoffs at the notion of boundaries, blinded by his lack of self-reflection and self-criticism just like the imperial nation whose colors he wears.

In a drastic reversal from his characteristic arrogance, Tony Stark takes the opposite approach from his superhero comrade: “If we can’t accept boundaries, we’re no better than the bad guys.” Here, Stark is finally showing the self-awareness he lacked in the original Iron Man, when he rained missiles and bullets across the Middle East in accordance with his whims. The android Vision, another Avenger, goes even further than Stark when he says of the superhero team, “Our very strength invites challenge. Challenge incites conflict. And conflict breeds catastrophe.” On their own, these kinds of statements could be read as a critique not only of the Avengers but also of the American approach to security, whose global military overreach has consistently created threats in the name of deterring them. For example, America’s consistent military presence in the Middle East over the past two decades has led to the rise of extremist groups like ISIS. Instead, the film frames Tony Stark and the Vision as antagonists, the same way the American media class treats critics of American military hegemony: not as cautious bearers of necessary warnings, but foolish traitors whose only goal is to support America’s enemies.

Ultimately, this framing both relies on and reinforces the conceit of the aforementioned ubiquity of threats, a notion that has guided messaging of American foreign policy for far too long. In the case of the Second World War, the threats to democracy and freedom were indeed quite genuine. Germany, Italy, and Japan were imperialist powers controlled by ruthless or even genocidal dictators, and without the efforts of the United States and Soviet Union (whose overwhelming role in defeating the Nazis has been conveniently whitewashed from American history), we might all today be living under a global fascist empire. World War II was one moment in human history where the good and evil sides were less muddled than, say, the geopolitical imperialist squabbles that sparked and sustained the slaughter of World War I. The reality was certainly more complicated than the jingoistic version we learn in our history classes, where all sides were brought into the dirt of the ravages of war. No matter: since 1945, our country has held on to the notion of American infallibility practically as gospel, even as our enemies have changed from the Soviet Union and its communist satellites to Middle Eastern dictators to terrorists and now back to Russia and China.

Perhaps producers Isaac Perlmutter and Kevin Feige sat through numerous meetings with Department of Defense officials who compelled them to craft the installments of the MCU as effortless propaganda of the American military-industrial complex. Just as likely however, is that the MCU’s military cheerleading is a side effect of the film studio’s obvious goals to assert a cultural preeminence that can only be achieved without challenging or upsetting any established cultural norms. What Noam Chomsky discusses in Manufacturing Consent, whereby news media self-censors on behalf of their corporate overlords, is the same king of logic that drives the production of summer action flicks like Top Gun: Maverick (as much an extended recruitment ad for the Navy as its predecessor) or artsier equivalents like Zero Dark Thirty (which celebrates the American special forces’ assassination of Osama bin Laden). Instead of setting these stories in the real world, the creators place the MCU in a heightened reality, one where the filmmakers have dared to put wizards and robots on the same battlefields but have not been so bold as to challenge the American empire.

As more and more Marvel movies are released, they tend to draw their primary weight less from their individual stories and more from continued references to the franchise’s past and future. This approach is not necessarily a fault of the franchise per se : there is certainly a degree of logistical and creative ingenuity to the MCU’s self-referential storytelling, which has juggled dozens of heroes and villains across nearly a decade- and-a-half of film and television releases. Authors like William Faulkner or Gabriel García Márquez have similarly set many of their novels and stories in the same continuity with any number of the same characters recurring across narratives, to consistent critical and scholarly acclaim. Where Faulkner and García Márquez use this approach for thematic complexity and narrative/historical continuity, Marvel’s approach ultimately serves to encourage viewers to continue shilling out money year after year, release after release, just to keep everything straight.

With each Marvel movie released, it becomes harder and harder to follow them without knowing the context of the preceding dozens of films and television episodes. Even people who have watched most if not all of the MCU properties, like me, might have trouble keeping track of all the crisscrossing references. With this approach, all Marvel movies, no matter the intellectual property they are adapting, are forced to conform to a general stylistic and tonal formula, wherein formula supersedes risk and conformity supersedes creativity. As the years have gone on and the MCU has grown larger with each passing film, the franchise is content to recycle accumulated cultural cachet in the place of making any narrative or stylistic choice that might upset the delicate balance of its curated uniformity. After all, why do something new that might attract a smaller, more niche group, when you could continue to write for a broad and an already captive audience—and their money?

This approach is perhaps most evident in the most recent Spider-Man film, Spider-Man: No Way Home. In an example of cooperation within the capitalist class that the modern Left can still only dream among our own disparate factions, Sony and Marvel Studios reached an agreement that allowed Marvel to use the Spider-Man character, whose license was still owned by Sony, and his concomitant properties, within the MCU in exchange for a split of the profits. After the beloved character’s multiple previous appearances in a portrayal by young upstart actor Tom Holland, Spider- Man: No Way Home took it one step further by bringing in actors from both series of previous Spider- Man films of other corporate continuities, recast now as alternate versions from different dimensions. The result is less a movie that stands on its own than an extended montage of references and callbacks to, or even reimaginings of, characters and moments from preexisting films, the accumulation of which winds up significantly weaker than the sum of its individual parts.

For someone like me, who grew up watching the other on-screen iterations of Spider-Man (Tobey Maguire from 2007 and Andrew Garfield from 2014), seeing these other actors play Spider-Man again might be meaningful, a flashback to your childhood. But if you’ve never seen the movies featuring Maguire or Garfield as the web-slinger— or if you’re re-watching No Way Home, when the surprise is no longer a surprise—these actors’ presence is a largely hollow attempt to trigger a nostalgic joy you may have once felt watching earlier, better movies. Instead of creating new films with their own emotional weight, the filmmakers rely on the work done by previous films as a shortcut to audience investment, all part of a growing Hollywood tendency to capitalize on nostalgia through big-budget quasi-remakes (one 2018 article in Den of Geek detailed their anticipation for 121 remakes of older films). Where a film like the live-action reimagining of The Lion King at least reimagined everyone’s favorite singing animals through impressive photo-realistic imitations, the Marvel Cinematic Universe banks purely on our desire to revisit what we already know and love rather than attempt to break any new ground. One could argue that the same could be said of any adaptation from one medium to another, whose very existence is predicated on bringing to life an already familiar storyline, setting, or cast of characters. But the most recent outings of the MCU represent the laziest, most facile approach to making interesting cinema by assuming the audience is already interested. Sometimes, this approach even seems to work, less a result, however, of the quality of the films themselves than of the encompassing totality of the corporate machine that has come to dominate the cinematic market.

But are Marvel movies even cinema in the traditional sense? Acclaimed American filmmaker Martin Scorsese doesn’t think so, at least not in his widely discussed opinion piece for the New York Times where he described Marvel films as more akin to “theme parks’’ than artistic achievements. He writes, of the films of the MCU:

“Nothing is at risk. The pictures are made to satisfy a specific set of demands, and they are designed as variations on a finite number of themes. … [They are] market-researched, audience-tested, vetted, modified, revetted and remodified until they’re ready for consumption.”

Canadian director Denis Villeneuve takes a similar tack:

“The problem today … well, if we’re talking about Marvel, the thing is, all these films are made from the same mold. Some filmmakers can add a little color to it, but they’re all cast in the same factory.”

It might be easy to call Scorsese and Villeneuve’s ideas elitist, and they might be. Who gets to define cinema? Does the average moviegoer care whether this or that film conforms to such a definition? After all, not all movies need to be black-and-white character studies of aging boxers or mentally disturbed gangsters to be enjoyable art. But the films of the Marvel Cinematic Universe are creations that never truly aim to break any new kind of cinematic or artistic ground, settling for infinite variations of the same dull formula. Scorsese is certainly right that they’re “made to satisfy a specific set of demands,” “as variations on a finite number of themes.”

It’s easy to write off Marvel films as populist drivel, movies so middling and formulaic as to be beneath substantive criticism, but to do so ignores the importance storytelling plays in shaping and reaffirming cultural and political attitudes. We can’t allow ourselves to settle for imperialist propaganda in our search for fantastical entertainment. Why should we, with the existence of a movie like Howl’s Moving Castle, a thrilling fantastical adventure of milliners and wizards and demons, and a heart-rending screed against endless war? Or a television show like Avatar: The Last Airbender, which deftly explores questions of imperialism, propaganda, and genocide with both nuance and clarity? How about a movie like James Cameron’s Avatar, which despite its relatively formulaic and straightforward plot at least gives us an anti-colonialist allegory? Or, perhaps most of all, the recently released masterpiece Everything Everywhere All at Once, which takes the concept of a “multiverse” and uses it not as an excuse to mash together a montage of corporate nostalgia but instead turns it into a brutal yet hopeful (not to mention class-conscious!) rumination on existential despair?

There is a place for superhero films, for movies that allow us to get lost in otherworldly adventures, whether as ruminative art or even just rip-roaring entertainment. But such movies should not have to conform to our preconceptions about what an action-adventure story can be, nor should they merely serve to reinforce cultural and political norms. Art and storytelling are crucial sculptors of our cultural consciousness, and there is no doubt they can be wielded for radical ends, ends that make us reconsider the world and our relationship to it and to one another. Just like their anti-communist comic book writer predecessors, the makers of the MCU surely understand the power of art to influence and subvert. Otherwise, they wouldn’t be so committed to making their films vehicles for liberal imperialist propaganda—or they’re too clueless, too inept, or too dull to see that liberalism is far from the most interesting or novel lens through which to tell a compelling story. Now, with the possibility of World War III looming over us and the American experiment revealing its failure more and more every day, it’s more important than ever to call out this propaganda and the business model that reinforces it.