NPR is Not Your Friend

NPR is a problem. Good and proper leftists who read Current Affairs may already realize this. “Of course. NPR (Neoliberal Propaganda Radio) is a bastion of establishment groupthink and orthodoxy that gives cover to imperialism and corporate capitalism.” By contrast, readers on the Right who find themselves consuming Current Affairs may have an equally disdainful but entirely different critique. “Of course. NPR is an elitist liberal propaganda cult that serves as a mouthpiece for the Democratic Party, is openly hostile to any conservative voices, and ought to be defunded!”

Well, you’re both kind of right, and both kind of wrong.

NPR, originating like PBS from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, was originally envisioned as an ad-free public service to all Americans, standing as a supplement to privately owned commercial media and which would do the reporting that others did not. Yet, like much other media, NPR has become a partisan news service with a sterile, professional tone that belies an underlying allegiance to a very narrow range of political viewpoints that are largely inoffensive to those in power. Today, NPR is a product stuffed with advertisements. It receives relatively little in government funding and is mostly paid for by corporations and a small percentage of its listeners who come from a very specific demographic: white, well-educated liberals. NPR’s shift in funding and ethos means the outlet has come to exhibit some of the worst pathologies found in the commercial mass media.

NPR is not our friend. Let’s take a closer look at why this is.

NPR’s reach has grown considerably since its founding. Its programming reaches approximately 57 million people every week, while its flagship drive time newscasts, Morning Edition and All Things Considered, are in the top 5 highest rated radio programs in the country, pulling in close to 15 million listeners per week. Needless to say, NPR has an enormous influence over the national conversation, particularly amongst its mostly liberal listeners.

In a world full of overtly partisan outlets such as CNN, Fox News, MSNBC, The Atlantic, Infowars, The Daily Wire, and many others, one might be tempted to think that National Public Radio is a relatively moderate voice of reason amongst the sound and fury: a benevolent public service funded by the taxpayer, as friendly, essential, and innocuous as the Post Office.

NPR has “objective and balanced coverage.” That’s the assessment of Jack Mitchell, the first producer of NPR’s All Things Considered, who spoke with me recently about the evolution of NPR over the years. (He left the organization over 25 years ago and is now professor emeritus at University of Wisconsin-Madison.) Regarding the quality of NPR’s coverage, Mitchell said, “it’s not that different from the tone of the New York Times.” (Sadly, true.)

According to NPR’s Ethics Handbook, “Fair, accurate, impartial reporting is the foundation of NPR news coverage.” However, it is critical to understand that there is no such thing as impartiality in the media. The decisions made every day regarding what stories to cover, how much time to devote to a particular point of view, whom to talk to, whom not to talk to, and what tone and style should be employed when telling a story all represent subjective positions and points of view. Anyone who claims that their outlet is “objective” is high on their own fumes. NPR’s own Nina Totenberg concedes this point. (She said: “Objectivity should never be confused with fairness. Nobody is purely objective. It is not possible. … What all of us are capable of is fairness.”)

Like all press outlets, NPR has a particular point of view. Its bias is just as profound as the likes of MSNBC or Fox News. NPR’s ideological bias is toward what we might call the American bipartisan consensus. Roughly speaking, this consensus assumes that the following are not to be the subject of serious public, or, for that matter, private, debate:

- The primacy of capitalism or the “free market,” and the idea that our economic system simply needs tweaks to make it work better for all, as opposed to fundamental redesign

- Globalization and “free trade”

- War, militarism, and U.S. hegemony

- Meritocracy and credentialism

- Liberalism, a.k.a. “the politics that puts pride flags on police cars or gives us Pepsi commercials with Black Lives Matter themes, but will not actually redress the racial wealth gap or meaningfully curb the impunity of our militarized police.”

This consensus in the media tends to show up in outlets’ reliance on establishment talking-heads, government officials, mainstream think tank fellows, experts, and corporate mouthpieces to help “analyze” the daily news. Ralph Nader has pointed out that such “interviewees have economic and ideological axes to grind that are not disclosed to the general viewers, listeners and readers, when they are merely described as ‘experts.’”

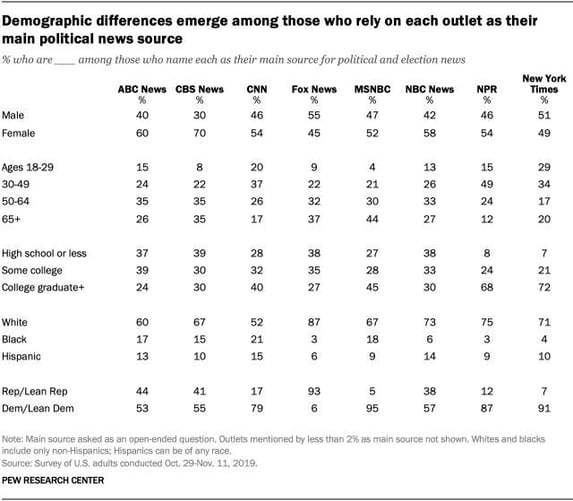

NPR’s bias is perhaps more pernicious than other media networks because it presents itself as a model of “objective” journalistic integrity and balance, posturing as an institution that is above all of the common rage-selling, opinionating, and infotainment. One fact that should make us suspicious of that idea is the political orientation of its listenership. According to 2019 Pew research data (shown in the table below), in terms of listener partisan affiliation, NPR is the fourth most partisan network behind MSNBC, Fox News, and the New York Times. The NPR listener base is also highly skewed toward the white, liberal, relatively young, and highly educated. Eighty-seven percent of NPR listeners support the Democratic Party or lean that way. Sixty-eight percent of listeners are “college graduates +”, making NPR the second most skewed by education, after the Times. As Michael P. McCauley puts it, rather smarmily, I must say, in his book NPR: The Trials and Triumphs of National Public Radio, “a college education—and the mature set of values that comes with it—is the primary variable that predicts whether a person will listen to public radio.” Additionally, 75 percent of listeners identify as white, only second to Fox News’ 87 percent white.

“[NPR is] liberal, no question,” Mitchell says. “But most listeners who listen to it don’t perceive that, because they’re liberal too. And it seems right.” Mitchell characterizes the politics of NPR staff and listeners:

“They are sympathetic to gay rights, 30 years ago before it was fashionable, women’s rights, Black Lives Matter. This is all stuff that resonates with the socially liberal, college educated people who make up much of the Democratic Party and who make up much of the public radio audience. There is not much interest in major economic reform among those audiences. I mean, they’re doing pretty well themselves. … I don’t think very many public radio listeners or staff really want to break up General Motors. Or break up Amazon. There’s not an economic liberalism that goes along with the social liberalism. And I’d say that’s true of the mainstream Democratic Party. … It’s that the comfortable audience doesn’t want to become economically uncomfortable. It’s just not something that burns in their souls: ‘What are we gonna do about economic reform? Corporate reform?’ Antitrust—who talks about that anymore? Public radio was never radical. The New York Times was never radical. Mainstream media are not radical.”

Mitchell notes that media outlets have shifted to a model of appealing to very particular audiences along cultural and ideological lines. As Fox News cornered the market on the demographic of “55 to dead” (in the words of the late former network boss and infamous serial sexual harasser Roger Ailes) and became the most watched cable news station in the country, other outlets began following the same model of picking a political side that appealed to a particular population and sticking to it. McCauley, a former radio journalist and current professor at the University of Maine, says that for public radio, this fixation on catering to the values of a particular audience is seen as necessary to its financial survival. “Audience research helped public radio fuse its programs more snugly to the values, beliefs, and attitudes of the people who tuned in (and pledged their financial support) most often,” he writes.

Those who have worked in public radio, such as McCauley and Mitchell, recognize that no single radio station can try to serve the entire public. “Our media is so splintered that I’m not sure there can be a place that everybody trusts or feels confident in,” Mitchell said, “because they’ll have lots of places that they can go to where they hear nothing that’s going to be bothersome to them. Why make yourself uncomfortable when you can be in a comfortable place? Be it Rush Limbaugh or NPR? Who wants to be uncomfortable? Who wants to be questioned?”

Over the years, then, NPR has essentially become a product specifically designed by its liberal, college-educated staff, paid for by its liberal, college-educated listeners, and sponsored by corporations who pay for access to that audience. NPR’s website for corporate sponsorship explains that “NPR has no list of sources from which funding will be refused,” and NPR has repeatedly defended its practice of accepting corporate sponsorships from the fossil fuel industry, including ExxonMobil and America’s Natural Gas Alliance. It has justified this practice on the grounds that “to impose a litmus test to accept or reject funding from an organization would create the appearance that NPR as a news organization has taken a position on the issues related to that organization.” By this logic, NPR would no longer “be seen as fair and unbiased if someone inside the organization had decided that sponsorship from one side or the other was objectionable.” (NPR entices corporate sponsors in part by touting the “halo effect” that it can give to their reputation, meaning “the positive association and shared values that NPR listeners attribute to the companies that sponsor us.” If the effect is real, and NPR insists it is, then by their own admission they are burnishing the reputation of the fossil fuel industry by accepting funding from that industry.)

NPR’s leadership has fully bought into this kind of funding model, with corporate advertisements, once considered verboten, now being an accepted facet of NPR’s news programs. This reliance on securing corporate dollars using the lure of NPR’s “well-off” audience very much influences the programming decisions of the organization. NPR’s former president Delano Lewis once spoke to McCauley about the need to attract corporate dollars: “If you’re going to solicit money from corporations or foundations, … they are interested now in your reach. They’re interested in the audiences that you serve, and the returns that they may see from reaching those audiences.”

Some programs just don’t make the cut. In 1995, NPR canceled nine of its cultural programs, some of which were meant to serve minority audiences, and 20 people lost their jobs as a result. McCauley notes that Lewis “regretted the loss of these programs but said their small audiences attracted little in the way of badly needed private funds.”

In light of NPR’s partisanship and problematic funding, it’s difficult to see how NPR is capable of fulfilling its original mission to be an ad-free, noncommercial service operating chiefly in the interest of the diverse public. But that’s exactly what NPR was supposed to be.

The History of NPR: From Populism to Professionalism

The history of NPR starts in 1967, with President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Public Broadcasting Act, which established the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), under which NPR would be founded in 1970. In a November 1967 speech, Johnson made clear that the intention of the Act was for broadcasting to serve the public interest, as well as to provide education. It was not simply to be a mouthpiece of the state or a particular political party that happened to be in power:

“The Corporation will assist stations and producers who aim for the best in broadcasting good music, in broadcasting exciting plays, and in broadcasting reports on the whole fascinating range of human activity. It will try to prove that what educates can also be exciting. It will get part of its support from our Government. But it will be carefully guarded from Government or from party control. It will be free, and it will be independent—and it will belong to all of our people.”

At the outset, NPR emphasized drawing from the voices of “the real people, not the experts,” Mitchell said. It was to “be representative of the entire country. The assumption was that all kinds of people would listen to this because all kinds of people were represented.” NPR’s first mission statement, the NPR Purposes, written by Program Director Bill Siemering, called for NPR to “celebrate the human experience as infinitely varied rather than vacuous and banal,” help citizens develop “a sense of active constructive participation [in society] rather than apathetic helplessness,” and “speak with many voices and many dialects.”

Siemering had not been a journalist. His background was in educational radio, and Mitchell recalls him as “a philosopher, a dreamer, a wonderful human being” who believed in featuring common people:

“Siemering had said, ‘why do we always have to start All Things Considered with what happened at the White House today? Maybe somebody got a job in Philadelphia. And maybe that’s a big deal for that person. Why don’t we lead with that?’”

McCauley notes that before NPR, Siemering had opened “a storefront [radio] studio in a minority neighborhood, [that] helped residents communicate their interests and concerns to a wider audience.” McCauley writes that Siemering had a “1960s mentality” of wanting to “uplift the downtrodden masses,” and quotes the Corporation for Public Broadcasting’s Al Hulsen:

“I think there was a whole group of people, [and] Bill Siemering stands out among that group, that said, ‘There are resources all over the United States that can be tapped for national enlightenment; that ideas are not restricted to the East Coast or Europe. They’re all over the world in the smallest places, in the biggest places. There are brilliant minds everywhere that could solve human problems, and put society ahead, and stop war.’”

For a time at the start, NPR prominently did feature average people in its programming. Mitchell described “the early days” when they would call up people around the country, “observers,” such as a man named Charlie in Kansas and a woman in Wisconsin, to get their opinions. NPR used to have what they called “Sound Portraits,” interviews with everyday people talking about their occupations, from mechanics to balloon salesmen. “Real voices,” Mitchell calls them.1 Mitchell also recalls their method of covering a strike at a Chevrolet plant in Ohio. “So we got the phone number of the telephone booth in the lunchroom at Lordstown. We called it, and whoever answered the phone, we talked to them.”

But, as Mitchell admits, Siemering’s vision was “highly romantic” and “not terribly realistic. … No radio service serves everybody.” At the same time, “I thought we were an alternative to the mainstream media,” Mitchell said in an interview with Current. “By 1978-79, about the time that Morning Edition began, NPR made a real major change of pace to move from being an alternative to being competitive. That, I did not anticipate.”

Taking the advice of private consultants, NPR decided to become more “respectable” and professional, giving voice to experts instead of average people and hiring more people with journalism backgrounds to staff its programs. The goal was to become the “best journalistic organization it could be,” says Mitchell. This also led to the exodus of the top management. A “liberal Democratic journalist,” as Mitchell describes Frank Mankiewicz, was brought in as NPR’s new president to reorient the stations. “He didn’t even care about any of that Siemering stuff. He just wanted to be the best.” As such, NPR “became overwhelmingly a very good mainstream operation,” Mitchell said.

Over the years, NPR has been able to cultivate a “very elite, good audience … a rather comfortable audience who would be willing to pay for it,” Mitchell said. Public radio now sells access to that audience to corporations. Today, public radio listeners and private corporations make up most of the funding for NPR. Corporate sponsorships comprise the largest portion of NPR’s revenue, totaling around 37 percent of its total budget. As Mitchell points out, there are two reasons NPR doesn’t need government money anymore: NPR gets a lot of private money, and “government never came through anyway.” McCauley wrote in 2005 that because “the amount of federal money earmarked for public radio has dwindled to about 14 percent of the industry’s annual budget (33 percent if you include money from state and local governments)” and “income from private sources such as pledge drives and corporate underwriting accounts for a little more than half of the funding mix, … America’s public radio system must, as a matter of survival, focus its programming and fund-raising efforts on the highly educated … audience that covets its programs most.”

NPR was originally funded entirely by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. That funding was significantly cut by 20 percent in 1983 under the Reagan administration. In a major shift for public radio, the bulk of the funding was then shifted onto the backs of the local public radio stations and their listeners’ wallets, as those stations now had to pay for access to NPR programming. CPB later received a 25 percent cut during the Gingrich-led Congress of the 1990s. (NPR has been a longtime target for defunding by the right wing. President Trump threatened to cut funding for CPB in 2020.) Facing decreasing funding from the federal government, instead of lobbying Congress for guaranteed taxpayer dollars, NPR’s then president Kevin Klose in 2003 secured a bequest of $225 million from Joan B. Kroc, heiress of the McDonald’s fortune. (NPR journalist Susan Stamberg joked about changing her name to Susan McStamberg.) It was this infusion of cash into NPR’s endowment which helped it to expand its news staff across the country and around the world. This is how our “public services” stay on life support—not through universal public funding, but through the whims of private philanthropy.

McCauley is blunt in defending NPR’s shift to serving educated elites and declining to produce programming that speaks to, or is spoken by, the disenfranchised, citing the superior market performance of the existing model:

“Many of NPR’s leftist critics assume that public radio should promote the interests of society’s disenfranchised groups, thereby helping them to gain a wider voice. … [The] logic fails on a number of counts. First, radio has become a narrowcast medium in which individual stations thrive by ‘superserving’ discrete segments of the overall audience. … If Pacifica [Radio] is committed to serving disenfranchised groups, there is no logical compulsion for National Public Radio to do the same. (NPR airs many stories and programs about these groups, phrased in a manner that speaks to the sensibilities of its core listeners.) If NPR stations offered something for everyone in their daily schedules, their overall appeal for current listeners would drop markedly.”

Mitchell doesn’t see NPR going back to the way it used to be, when programs took the calls of average listeners. He said: “People say their predictable things without real clash of opinions. … I’m an overly educated university person, just like most of [those who work at NPR]. … Real debate doesn’t happen on public radio, and I wish it would.” NPR’s Talk of the Nation, which did receive audience calls and emails, as limited and screened as they were, was canceled in 2013. (NPR officials said the decision was part of a “move away from opinion and toward straightforward storytelling.” But who gets to tell the stories?)

Mitchell adds that presenting opposing points of view is of interest to the general public according to the Fairness Doctrine, established in 1947, which, as explained on the Ralph Nader Radio Hour, “required licensed radio and television broadcasters to present fair and balanced coverage of controversial issues of interest to their communities.” In 1987, the Reagan administration rescinded the doctrine, which helped lead to the partisanship we see today on the airwaves and on social media.

Nader also laments that NPR’s airtime is increasingly intruded on by advertisements:

“What started as a ‘just a little bit of commercial sponsorship,’ when Congress got tight some years ago, has now gone wild. Do we really need to be reminded that ‘support for this station (or for NPR) comes from x, y, z contributors,’ about thirty times an hour? Mind-numbing, hour after hour!”

Ultimately, as the CPB notes on its website, public media is a “private-public partnership in the best tradition of America’s free enterprise system.” And that is exactly the problem. NPR has become a product of the free enterprise system rather than a truly public service which could bring listeners ideas that do not receive airtime on privatized media (ideas that also might happen to challenge that same free market system).

How NPR Operates

Let us now take a closer look at NPR’s chief limitations and biases:

- An ethics of “impartiality”

- Staffing choices aligning with the professionalization of journalism

- Deference to Democratic Party ideology

- An ideological proximity to powerful institutions which limits the scope of NPR’s news stories and precludes a political vision that might challenge the dominant ideologies of capitalism and militarism

First, let’s examine how NPR’s appeals to impartiality result in their journalists becoming what I call, “The Dispassionate Robots of NPR.”2 NPR’s ethics handbook says: “Fair, accurate, impartial reporting is the foundation of NPR news coverage.” Also from NPR’s ethics handbook: “We avoid loaded words preferred by a particular side in a debate. We write and speak in ways that will illuminate issues, not inflame them.” NPR claims that it is maintaining journalistic integrity by adhering to notions of “impartiality” and “avoiding loaded words.” But these are simply euphemisms for NPR’s choice to speak in inoffensive tones that are perfectly acceptable to elites. NPR chooses to refrain from using adversarial language in its news coverage. Such an approach is particularly bad for foreign policy coverage.

Take a recent example: the protests in Iran after the death of a Kurdish woman who had been taken into police custody for allegedly failing to abide by the dress code for women. Witnesses say she was beaten by police, according to the Guardian. NPR’s choice of words about the protests? The Iranian protests are about “personal freedoms, the economy, the environment.” The word “sanction” appears nowhere in the NPR article even though Iran has been under some form of sanctions by the U.S. since 1979, the year of the Islamic Revolution (with brief pauses during the Obama and Bush years for humanitarian crises and as part of the nuclear deal, which Trump then withdrew from). Might U.S. sanctions have something to do with the “economy” as NPR puts it? World Socialist Web Site more accurately describes the situation: “The protests are being fuelled by a rapidly deteriorating economic crisis, produced above all by the devastating impact of a brutal sanctions regime enforced by the imperialist powers that is tantamount to war.”3

Another example comes from 2009, when NPR defended its position of not using the word “torture” to describe the torture that was carried out by the CIA and the military under the Bush administration. NPR ombudsman Alicia C. Shepard said:

“the word torture is loaded with political and social implications for several reasons, including the fact that torture is illegal under U.S. law and international treaties the United States has signed.”

So, out of a desire not to inflame or use words with “political” implications, we should avoid calling something torture even when it’s torture. Even though “enhanced interrogation” was a crime, we don’t want to sound like we’re accusing any powerful people of having committed a grievous crime. Shepard went even further in response to backlash that NPR received from listeners, stating that, “the bottom line is, whether waterboarding is torture is still a matter of political debate, even if some listeners don’t agree.” It is not just “some listeners” that don’t agree, however. It’s also Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, The Committee Against Torture, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, and the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Listen to editor-in-chief Nathan J. Robinson on Ear to the Pavement podcast (2017) discussing NPR’s preoccupation with “objectivity.”

The prohibition on “loaded words” meant that NPR would not call torture torture. It also means that NPR will not call the apatheid state of Israel, a key U.S. ally, the apartheid state of Israel, despite the judgments of Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, B’Tselem, and the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights in the occupied territories. NPR further defers to Israeli interests by never using the “State of Palestine” label for the State of Palestine. The NPR style guide’s entry on Israeli settlements in East Jerusalem says:

“Do not use words like disputed or controversial. While these are not wrong, they are inflammatory, and any word is going to be disagreeable to someone. Just say East Jerusalem, West Bank, settlement, without descriptives.”

So NPR journalists cannot even say the Israeli settlements are controversial (they are), let alone that they are illegal.

Nor will NPR say that the U.S. war in Iraq was a criminal invasion. It will not dare to call figures such as Henry Kissinger, George W. Bush, Dick Cheney, and Barack Obama what they clearly are: war criminals who must be brought to justice for the countless deaths they have on their hands. It will not call the CEOs and the Wall Street tycoons who orchestrated the financial crisis with its resulting millions of foreclosures, firings, and erasures of savings accounts what they truly are: thieves that are walking around scot-free with our money.

Avoiding “loaded” language does not mean that you are being fair and balanced. It means that you are perpetuating injustice in the service of powerful, venal human beings and their allies.

Narrowly Diverse Viewpoints

NPR claims it values a diversity of perspectives. According to NPR’s ethics handbook:

“Hearing from a variety of people makes our journalism stronger and more complete. In our reporting, we seek various perspectives on an issue, as well as the evidence supporting or countering each one. We try to understand minority viewpoints as well as those of recognized authorities; we don’t ignore perspectives merely because they are less popular.”

Yet in the very next paragraph, NPR admits it will give more coverage to those in power:

“Those individuals whose roles give them an outsized influence in how events play out will necessarily receive more attention in our news coverage. But it’s important for our audience to hear from a variety of stakeholders on any issue, including those who are often marginalized.”

So much for treating our friendly neighborhood balloon seller as equally worthy of airtime.

Perhaps not surprisingly, NPR has found the gender and racial diversity of its shows lacking, noting in 2018 there was “much work ahead.” “Voices heard on NPR weekday news magazines were 83% white and 33% female.” The problems go beyond race and gender, however. It is difficult if not impossible to find National Public Radio giving fair hearings to any members of the public who articulate views that are considered to be from the political wilderness. Where are the public anti-imperialists, socialists, anarchists, communists, fascists, fundamentalist pastafarians, radical environmentalists, Black nationalists, pan-Africanists, or anti-state militants being asked what they think about the news? NPR’s “impartiality” doesn’t have much room for non-mainstream voices. Many perspectives actually do get ignored on NPR. The typical commentary we hear on the radio consists of a dismal interview with a member of the U.S. State Department followed up by a counterpoint offered by an employee of a think tank.

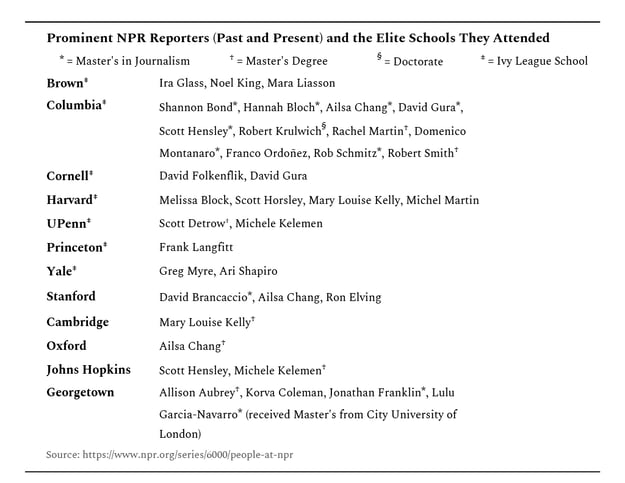

Once an original staff of eclectic amateurs, NPR has gradually succumbed to the same staffing biases that are seen within the larger media ecosystem. There is a bias in the media industry toward hiring college-educated journalists, often from elite universities, who primarily express the values of their class and cultural background. This accreditation of journalism—where the work becomes more like an official class that you belong to instead of something that you do—saps any radicalism from the profession and creates an insular, if not to say incestuous, culture. Poor, working-class, and high school graduates are marginalized from the profession. Thus, the range of thought narrows.

Matt Taibbi writes in Hate Inc: Why Today’s Media Makes Us Despise One Another about how journalism positions are increasingly occupied by college graduates:

“In America the change came in stages. When journalism became cool after All The President’s Men, upper-class kids suddenly wanted in. Previously a rich American kid wouldn’t have wiped his tuchus with a reporter. […] The Internet accelerated the class divide. Big regional newspapers increasingly became national or even global in mind-set. In the digital age it made more sense to design coverage for a sliver of upper-class readers across the country (who could afford subscriptions and responded to ads). … Because news organizations were targeting those audiences, it made sense to pick reporters who came from those ranks as well. By the mid-2000s, journalists at the top national papers almost all belonged to the same general cultural profile: liberal arts grads from top schools who lived in a few big cities on the east and west coasts.”

Taibbi was mainly describing for-profit outlets such as the New York Times and the Washington Post, but NPR is subject to this same trend as well. Take a look at the following table showing prominent NPR reporters and their alma mater:

It should be noted that the term “elite” has been weaponized by the Right to promote a kind of faux populism in reaction to any whiff of progressivism. But conservative elites tend to be educated at the same institutions as liberal elites. Graduating from an elite institution does not guarantee a particular party preference. Elites on either side of the narrow political party spectrum tend to fit comfortably within the mainstream, bipartisan consensus.

Now, a reporter’s class and educational background are not necessarily determinative of the kind of reporter they will be. But as the profession of journalism becomes more homogenized and professionalized, it perpetuates the dominant ideologies that are so embedded in our academies and political institutions. As Todd Gitlin puts it in The Whole World Is Watching:

“[J]ournalists are socialized from childhood, and then trained, recruited, assigned, edited, rewarded, and promoted on the job; they decisively shape the ways in which news is defined, events are considered newsworthy, and objectivity is secured. News is managed automatically, as reporters import definitions of newsworthiness from editors and institutional beats. … Simply by doing their jobs, journalists tend to serve the political and economic elite definitions of reality.”

If you want to argue that an elite education and an advanced degree are valuable assets when working as a reporter, that this education broadens your perspective and gives you more ideas with which to bolster your analysis, fine. But we must acknowledge that our universities have become subservient to corporatized and militarized research and funding, and our academies function less as makers of citizens than as specialized career mills. The intellectual independence and moral integrity of higher education in the U.S. has become so degraded. Those who are nurtured in such institutions tend to spout mainstream worldviews. We cannot pretend that earning an advanced degree in today’s educational environment gives someone the magical ability to present news and analysis that does not reflect the interests of the class that they belong to. We must subject to skepticism any journalist who ought to be using their role to antagonize power but instead chooses to rub shoulders with power.

Consider what would happen if NPR were to hire a bunch of working-class, unaccredited reporters, hosts, pundits, and producers for their daily shows, culled from divergent, leftist, unapologetically anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist outlets (e.g., Jacobin, Truthout, World Socialist Web Site, Black Agenda Report, The Empire Files, The Grayzone, BreakThrough News, Monthly Review, Consortium News, MintPress News, Multipolarista, and others), and those new reporters maintained the same quality of work that they’ve been producing under their independent outlets. Such adversarial staff would not follow the current NPR approach of using narrowly defined language to bias its coverage in favor of the capitalist status quo. What would happen? NPR would likely see its substantial corporate underwriting and institutional access completely cut off, not because those leftist reporters are any less biased than the current coterie of NPR staff, but because NPR’s content and approach would be different from its current establishment bias. Divergent voices would never be allowed to have a substantial mouthpiece in an establishment media outlet such as NPR—at least, not without a goodly amount of “correcting,” perhaps Delbert Grady style.

Ultimately, the elite tone of NPR, coming as it does from a professionalized staff, “turns off a lot of people,” said Mitchell.

“They use language that people don’t easily understand or aren’t comfortable with. It’s not language they would use … And [the hosts] don’t even know they’re doing it. It’s just the way they talk. They think it’s conversational. And it is for them, but the social divide is quite different.”

McCauley attributes the tone of NPR directly to the educational backgrounds of its reporters:

“The rational, fair, and balanced inquiry that is heard on NPR News is a function of the educational attainment of the network’s journalists and listeners and the value systems these people have developed through higher education.”

What NPR describes as their standard tone of cordiality, Nader more accurately describes as “commercialism and amiable stupefaction.” The polite, upper-crust tone, representing, in fact, a narrow worldview, conveniently tends to serve institutionalized power.4

The elitism of the media mirrors the worsening political divide throughout the nation. Mitchell went on:

“[NPR listeners] really don’t have much respect for anybody who voted for Donald Trump. Well, half the country did. That’s a pretty big blind spot if you’re trying to work in a democracy and you want a functioning society. You really do have to not only understand but respect. NPR will go out and interview some people, but it’s like sending some correspondent to a foreign country. ‘Oh, what an interesting people you are.’ That kind of attitude.”

A kind of vicious cycle occurs where the tastes of professional, liberal reporters are reflected by the professional, liberal audience, and vice versa, creating an establishment echo chamber. Describing the tastes of the public radio audience, McCauley writes: “NPR listeners are more likely than average to partake in just about any kind of leisure activity including exercise, sports, dining out, and attending live musical and theatrical performances. Nearly 70 percent purchased books over the year that culminated in NPR’s 2003 audience survey.” Books! They buy books! Seventy percent of NPR listeners purchased at least one copy of The Da Vinci Code and The Secret! That’s how you know they’re real smart.

NPR’s Deference to the Democratic Party

NPR’s audience and staff is composed overwhelmingly of college-educated liberals, the same demographic that dominates the Democratic Party. As Thomas Frank explains in Listen, Liberal:

“Today, the Democrats are the party of the professional class. The party has other constituencies, to be sure—minorities, women, and the young, for example, the other pieces of the ‘coalition of the ascendant’—but professionals are the ones whose technocratic outlook tends to prevail. It is their tastes that are celebrated by liberal newspapers and it is their particular way of regarding the world that is taken for granted by liberals as being objectively true.”

NPR’s coverage will generally frame things in ways that stay within the bounds of the Democratic Party line. For example, in a discussion between NPR’s Mary Louise Kelly and Mara Liasson, the two poo-pooed Bernie Sanders’s 2020 campaign with uninformed opinions presented as fact. Most glaringly, they stated confidently that Sanders’s progressive policy proposals such as Medicare for All are “unpopular” even though consistent polling shows that they are indeed popular. Undermining Medicare for All with misleading statements falls in line with the official Democratic Party platform which emphasizes expanding “access” to private health insurance for privatized medical care, not universal socialized health insurance. Piece after piece on NPR mocked Sanders’s electability prospects despite his campaign’s record-breaking small-dollar donations, polling which showed he fared better than Trump, and the fact that significant numbers of people who voted for Sanders in the 2016 primary went on to vote for Trump and planned to do so again in 2020.

Besides NPR’s dismissiveness of the popularity of the Sanders campaign, NPR often gives cover to the ineptitude of the Democrats. In a recent story about President Biden’s dismally low popularity, NPR’s Domenico Montanaro blamed Biden’s poll numbers on Senator Joe Manchin’s “obstruction.” Manchin, assiduously serving as the “rotating villain,” is a perfect excuse for a conservative figure such as Biden to throw up his hands and say that he can’t accomplish any progressive proposals that he had no intention of making happen anyway, while reporters such as Montanaro give credence to the notion that Biden has his hands tied.

The story also notes that there is talk of a Democrat other than Biden running in 2024. Who does Montanaro list as potential candidates? The even more unpopular Kamala Harris and Pete Buttigieg. Who isn’t mentioned? Bernie Sanders. Our vision of the politically possible is thereby occluded by NPR. As professor Robin Andersen put it, the ignorance that undergirds the majority of analysis that is presented on NPR “is willful, and finds its roots in a profoundly ideological position, an ideology adopted by journalists who favor and are rewarded by corporate arguments promoted by corporate Democrats.” As media critic Normon Solomon put it, to the extent NPR is balanced, it is “ideologically balanced between the views of the Gingriches and the Clintons.”

NPR Gives No Sense of History or Context

NPR gets consistent criticisms from listeners about the lack of context they bring to news stories. NPR’s constant refrain in its defense is as follows:

“Radio reporter pieces and live interviews are bound by strict time limits, which sometimes leaves audience members frustrated at the lack of context included. Time is tight. A two-minute story can cover the day’s news, but does not allow for an explanation of the contributing factors of the last 50 years.”

This argument implicitly accepts “strict time limits” as a legitimate way to do journalism. It fails to consider that shallow sound bites ought to be replaced by more substantive debate. As Nader points out, “very important subjects, conditions and activities not part of [NPR’s] frenzied news feed are relegated to far less frequent attention.”

Let us look at a few topics where NPR leaves out a lot of essential information. First, take student debt. On November 16, 2021, NPR produced a story about student debt cancellation that would have you believe that all is rosy with the world and that the people in charge are benevolent and have our best interests at heart. The story, produced by Cory Turner—who has done some otherwise good reporting on student debt—focuses on the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program. This program, administered by the Department of Education, was intended to erase the remaining student debt of borrowers who worked in public service for 10 years. But the program is so poorly managed that people flock to Reddit for all kinds of advice and support on how to navigate the system. With some tweaks to the program, about $2 billion worth of loans have been canceled, a mere fraction of the trillions of dollars of total student debt. The story makes no mention of how our unjust system of funding higher education came about in the first place or the possible ways of transforming it. For example, NPR could discuss the possibility of tuition free public college, a highly popular policy proposal that would eliminate the need for students to take out loans. According to Pew, 63 percent of adults favor the policy.

Another NPR story concerns a program that was intended to put low-income student borrowers on track to getting their loans canceled. The program, again, is broken and woefully mismanaged. NPR’s story does not explicitly connect the problems of the program with the simple fact that the government contracted out loan servicing duties to private entities, a staple tactic of neoliberal regimes that consistently fetishize the supposed “efficiencies” of privatization. Tellingly, the on-air version of this story, which was given only 3 minutes on NPR’s Morning Edition, completely cuts out any mention of the demands for universal student debt cancellation, instead ending with a boilerplate quote from the Department of Education about how they will do better next time.

These student debt stories conveniently leave out a lot of crucial context that is unflattering to the powers that be and which makes these debt cancellations and interest pauses less worth rejoicing over. NPR does not mention the promises that Biden has broken over student debt (Biden’s recent promise of $10k of student loan forgiveness was much less in amount and scope than he’d promised) or how he could do much more to prioritize the education of our citizenry. These critical omissions give cover to the failings of the Democratic administration. The essential context and analysis that NPR fails to provide leaves the listener feeling like all our problems are relatively new and are being taken care of, that these issues are mere isolated blips on our path of progress.

Let us now turn to the issue of how NPR covers U.S. foreign policy. It is startling to see how often their stories give deference to the U.S. State Department and whitewash the crimes of aggression by the U.S. while at the same time emphasizing the crimes of our official enemies.

In just one revealing instance, an article by NPR’s Jason Breslow highlights various war crimes committed by Russia in Syria. Breslow doesn’t have the time to mention the litany of U.S. war crimes in Syria. Breslow makes no mention of the fact that the U.S. has been conducting a dirty war in Syria by funding anti-government jihadists (Al-Qaeda) to overthrow the Assad regime. Breslow particularly highlights Russia’s use of cluster bombs in Syria. Unmentioned by Breslow is that the United States, like Russia and Ukraine, has not signed the treaty which bans the use of cluster bombs. No mention is made of the U.S. using cluster bombs in Iraq and Afghanistan or of the U.S. selling cluster bombs to Israel and Saudi Arabia. Civilians are being killed years later by unexploded ordinance from these U.S. cluster bombs. This, apparently, is considered nonessential information by NPR when producing a story in the lead up to the U.S. providing billions of dollars of weapons to Ukraine (which are now flooding the black market).

Similarly, NPR can produce a story on the difficulty of prosecuting Russian crimes of aggression in Ukraine without giving any mention to how the U.S. undermines any accountability for its own criminal war of aggression in Iraq. NPR can have a story quoting Merrick Garland as saying, “there is no hiding place for war criminals,” without mentioning the fact that thousands of American war criminals from our many wars are living completely free and will likely never face an international war crimes tribunal such as we are currently attempting against Russia. This is Western hypocrisy, plain and simple, legitimized by NPR’s failure to air dissent.

NPR gives little voice to moral critiques of war, preferring strategic critiques of war. In the lead up to the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, NPR’s Melissa Block asked neocon Assistant Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz this question: “Now that the U.N. negotiations have become so prolonged”—meaning that the majority of the world was not willing to go along with the patently criminal U.S. invasion—“do you feel that it was a mistake to take that route, to go through the U.N., and has it complicated your military strategy?” More recently, in a conversation between NPR’s Sacha Pfeiffer and former NATO commander Philip M. Breedlove, the two go back and forth on whether or not the implementation of a no-fly zone over Ukraine is a good idea (it’s not). No one stops to consider the criticism that U.S. actions may be needlessly prolonging the conflict.

The failure by NPR to question the morality of U.S. foreign policy legitimizes the idea that we are unerring defenders of virtue who must stop at nothing to defend our allies from our demonic enemies. This leads to further acceptance of militarization and escalation, not diplomacy and peace. Military options are the only ones conceivable.

When NPR consistently fails to provide substantive disagreement or larger context on these issues, it is not a defensible mistake. It is ideology on the airwaves. As the late historian Howard Zinn put it: “You can’t be neutral on a moving train. … Events are already moving in certain deadly directions, and to be neutral means to accept that.” A news outlet such as NPR that wants to avoid sounding “anti-war” in order to be perceived as “balanced” and “unbiased” is not actually being impartial. It is being amoral and dangerous.

What NPR Could Be

It might seem pie-in-the-sky to transform NPR into a true radio of the people. After all, McCauley writes that “NPR clearly does not approach stories from the fierce, radical viewpoint of Pacifica’s Amy Goodman [of Democracy Now!]” But such a “radical” orientation should certainly be an aspiration for NPR. There are changes that could move the outlet in that direction.

Some steps are obvious, like not allowing lead reporters to be the best friends of the powerful people they’re supposed to be reporting critically on. Ralph Nader has outlined multiple ways in which NPR has strayed from its original vision and can do much to improve the quality of its coverage. Some of the things Nader suggests:

- Take a more aggressive stance in advocating for Congressional funding in order to reduce or eliminate reliance on corporate donors. Additionally, “NPR should reject ads from disreputable or criminal corporations.”

- Focus less on responding to what is in the national conversation and more on underreported stories.

- Focus less on entertainment subjects and celebrities and more on local civic leaders and organizations.

- Be more explicit about the root causes of inequality and impoverishment of the American citizenry. “Increasingly, corporate power is shaping an evermore dominant corporate state that allows mercantile values to seriously weaken the social fabric and moral norms of our society,” Nader writes. “Not many NPR reporters use words like ‘corporate crime,’ ‘corporate welfare,’ or cover the corporate capturing of agencies, the vast unaudited military budget, or many other realms of American life controlled by ‘corporatism.’ But then what can one expect when they ignore credible civic groups, who have timely evidence of such domination, and keep on interviewing one another inserting four-second sound bites to academics and consulting firms?”

Just having our public radio be fully funded with guaranteed public dollars would potentially go a long way toward allowing less mainstream views on air. Getting rid of the reliance on corporate funding would open up space for programming that is more experimental, less regimented, and unapologetically anti-corporate (just look at how the Works Progress Administration gave opportunities for more radical creators to make a living, leading to a flourishing in public art). And just as NPR underwent a major change in its culture and ethos in the late 1970s, it can do so again.

NPR ought to prioritize hiring talented reporters, producers, and managers from outside of the middle-class, college educated milieu. If the network wants to expand its listenership, instead of cynically targeting rich audiences in its pursuit of corporate sponsorships, while also avoiding the pitfalls of condescension, NPR ought to be staffed by working-class reporters, ideally those who have not been socialized by establishment newsroom culture. (I’d prefer working-class leftist reporters, but let’s remember that class solidarity extends beyond mere political labels.)

Mitchell was skeptical of NPR’s ability to change. “It’s become so big and so bureaucratic and so ingrown that I just don’t think it could change much,” he told me. “You would need a new organization.”

We must ask ourselves: given that NPR, in its staff, sources of funding, and its audience, is overwhelmingly liberal, white, and college-educated, what ever happened to the public in National Public Radio? Our citizenry lacks a national outlet which we can truly call our own, a radio which serves our interests, not the interests of the powerful.

My humble suggestion for a rebrand: TPR, The People’s Radio.

You can find Kody Cava’s writing on Substack at Weird Catastrophe.

In the balloon salesman audio, the broadcaster introduces Sound Portraits as a new form of “personal commentary” in contrast to the previous commentary on the show that had been provided by intellectuals such as “Haim Ginott, Russell Kirk, and Judy Bachrach, among others.” The snippets are fascinating in what they reveal about individual lives as well as society at large. Balloon salesman Johnson sings a song about making people happy with balloons and how he likes to see people happy even though he’s been through a lot in his life. He recalls being in the Army and being “messed up” by it and that he didn’t receive proper medical care and how this was “wrong” but he couldn’t get justice for it. But “I wasn’t going to give up,” he said. Auto mechanic McGinnis relates a perspective of class bias toward him as well as a criticism of classism in the U.S. He recounts that once he tells people in a conversation that he fixes cars, they only want to talk to him about what’s wrong with their car. He says he would love to draw or paint but his mechanic work pays well, so he has to do it. Then in the next breath he laments how “our craftsmen stink” and don’t “give a damn” about the bigger picture of their work. He argues that craftsmen in the U.S. take no pride in their work and are only after making their “best buck” and getting home to “booze, broads, and baseball,” unlike their European counterparts who “take pride in their work.” But he then blames the mechanics’ lack of pride on society’s classist lack of respect for the mechanic. ↩

NPR has an ethics handbook that, on its face, seems intended to ensure that no NPR employee engages in partisanship, unfairness, or what could be considered impropriety. Take for instance this excerpt on impartiality from the handbook: “We avoid speaking to groups where the appearance itself might put in question our impartiality. This includes situations where our appearance may seem to endorse the agenda of a group or organization.” This far-reaching description of what employees can and can’t do seems to dictate that employees can’t actually have opinions or participate in civic society. This rule didn’t stop NPR’s Ombudsman Jeffrey Dvorkin or NPR’s Juan Williams from speaking at the CIA on separate occasions upon the intelligence agency’s invitation. During his talk, Williams even went so far as to call CIA employees “‘the best and brightest,’ and said Americans admired the agency and trusted it ‘to guide the nation and the nation’s future.’” This is the same NPR that fired two employees at affiliate stations for daring to show up at Occupy Wall Street protests. Apparently that activity was an overt political statement that tarnished the credibility and “impartiality” of NPR. But being a guest speaker at the CIA is no problem. Journalists are considered impartial and are allowed to give talks to intelligence agencies so long as they go along with nationalist cant and cheer for the proper team, in this case the foreign-affairs-interfering, coup d’état-doing, domestic-surveilling, press manipulating, warmongering, torturing, and genocidal CIA. But if you express your opposition to those same warmongering institutions, now you’re being partial. Truth and justice are of minor concern for establishment journalists in comparison to “impartially” applauding our permanent, non-petitionable states within a state, the intelligence agencies. ↩

For a discussion of the “devastating impact” of sanctions on Iran and other countries, see our recent article. ↩

NPR is also routinely criticized by both the Left and the Right for a perception that the organization is homogeneous. As NPR admitted in 2005: “At NPR, there are discussions about whether the people who are attracted to work in public radio are too much alike. There is an increasing recognition that NPR needs to be a more diverse organization at every level—culturally as well as politically. And that’s a discussion that is long overdue.” ↩