How We Can Ease the Pain

As a nation in pain, we are sold pills for everything. What if we tried a different approach to ease our pain?

Content warning: Although this article does not discuss eating disorders, it does discuss fasting (drastic restriction of caloric intake).

As I write these words I am fasting. I have had nothing to eat for more than two days. No calories—only water, coffee, and tea. My mind feels sharp, my mood is calm, and the back pain that has dogged me for 20 years is abating.

Pain is commonplace. We all experience it as humans. But when it drags on for months and years, it can color every facet of your life. Chronic pain, generally defined as that which lasts longer than the time it takes tissue damage to heal, has proven a constant in mine—ever since having a spinal fusion as a teenager. Along with millions of other Americans who have chronic pain, I have learned to live with it. I go to bed with pain and greet it in the morning. I feel it creeping as I stand in line or sit at my computer or lift my daughter into the air. Over the years I have tried every technique imaginable to make it go away, some of which worked better than others—yoga, dieting, medical massage, chiropractic. But fasting has proven the only method that can fully banish it from my body.

The impetus to fast came in an intuitional flash. A few years back when the pain was really kicking, a little voice in my head told me to “stop eating,” and I listened to it. I didn’t know much about fasting at the time, or whether it was safe. But I decided to go with my gut, and I’m glad that I did.

We moderns are conditioned to eat at least three times a day, and the thought of not abiding by that rule felt nutty. There was a bit of Pavlov’s dog at play. At the end of one day without food my stomach was howling, and so was my mind. As dinnertime came and went I felt slightly crazed. But when I awoke the next morning that frenzied feeling was gone and I had entered into a decidedly calm state of mind. Moreover, my pain was melting away. It felt as if I had broken a spell, as much physical as mental in nature, which enabled me to move and think in new ways. All the chatter went quiet, and I began to perceive the world from a deeper seat of consciousness.

Since that time I have undertaken numerous fasts, some lasting as long as a week. And each time that I do I experience mental resets and successive ah-ha moments that seem to build upon each other. The cumulative effect makes me wonder: how else might fasting apply to a populace living in a consumerist society like ours? Could we improve the pain of our body politic by depriving ourselves of some exceedingly common yet insidiously harmful stimuli?

Not only calorically, but mentally, in terms of how we feed our heads: from sunup to sundown on polarizing news, pointless memes, mind-narrowing algorithms, and culture war fodder—all of which keeps us distracted and addicted, hooked on bad feelings over social media platforms owned by tech lord billionaires. The Gods of Silicon Valley won’t even let their own kids use social media precisely because it is designed to make us feel isolated, and their platforms manipulate our fears and appeal to our worst instincts, like a 2.0 version of the “opiate of the masses.” What would happen if we just put down our phones and unplugged for a day or two?

On YouTube there’s no shortage of ripped dudes with washboard abs swearing by fasting as a men’s health cure-all. Intermittent fasting specifically has become more popular, and there are numerous different regimens (drastically depriving one’s body of calories may not be safe or advisable for everyone, of course). But the shallow focus on looks (and even the more noble emphasis on health) often leaves out the long history of fasting as a spiritual tool to achieve transcendence. Jesus was said to have fasted in the Judaean desert for 40 days and nights. The Buddha beat him out by more than a week, lasting 49 days under a Rajayatana tree. Biologically speaking, humans evolved to live without food for long stretches of time—much longer than you might think. The world record was set in the 1960s by an excessively overweight Scottish man named Angus Barbieri who went almost entirely without calories for an astonishing 382 days.

Today, the scientific literature on fasting’s numerous health benefits is as robust as it is remarkable. Temporary abstaining from calories ameliorates a host of chronic diseases, such as diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, asthma and rheumatoid arthritis. It triggers a process called autophagy, where the body metabolizes damaged and dying cells for energy, which produces a powerful anti-cancer effect. As far as pain reduction goes, the research is still in its infancy. But the studies that exist are promising. Fasting has been shown to aid in the production of ketones, an alternative energy source with powerful antioxidant properties (the ripped dudes on YouTube love this); it reduces inflammation, promotes neurogenesis (or the growing of new nerve cells, as one mouse model study showed), and releases serotonin, a neurotransmitter that boosts your mood and helps you sleep. In short, fasting helps heal your body.

What is even more intriguing is that fasting may also repair your mind. Brain plasticity, or neuroplasticity, refers to the way the brain can change its structure and develop new connections over time. “Periods of heightened plasticity have been traditionally identified with the early years of development,” according to a 2016 paper published in The Journal of Pain. But more recent research “has identified a wide spectrum of methods that can be used to ‘reopen’ and enhance plasticity and learning in adults.” Intermittent fasting was one of the key methods that was hypothesized to promote “healthy neuroplastic changes” by disrupting deeply embedded mind-body connections. As the authors explain: “Neuroplastic changes in brain structure and function are not only a consequence of chronic pain but are involved in the maintenance of pain symptoms.”

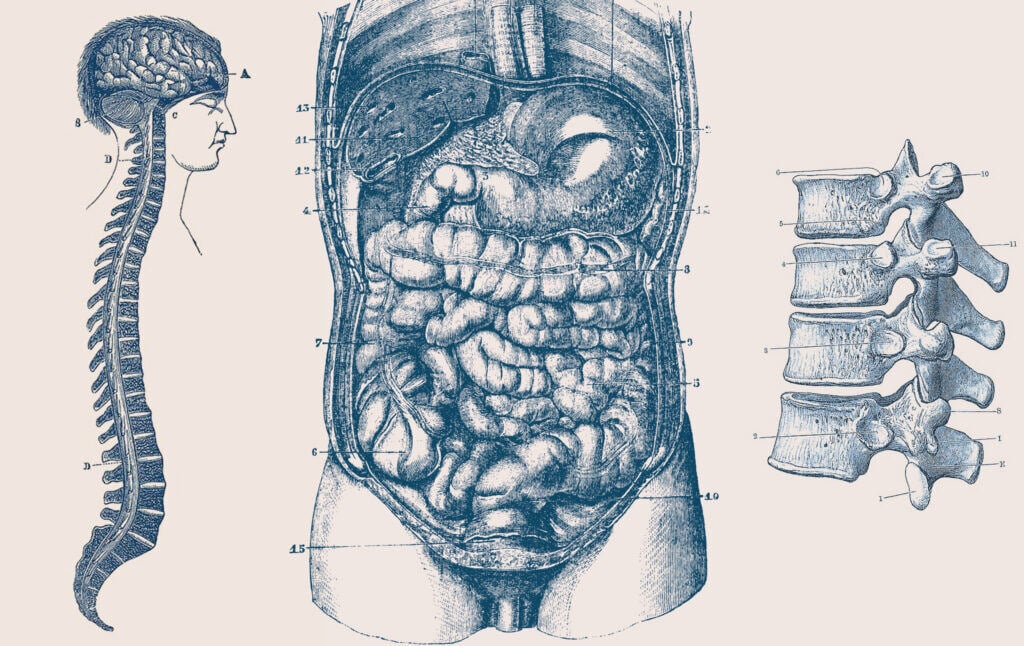

Before going on, I would like to introduce you to my screwed up spine, or the whole reason I started fasting in the first place. Back in the late 1990s when I was 15 years old, I discovered a bulge on my back. I had no idea what it was, so my parents decided to take me to a nearby hospital. As I sat in a waiting room, I spied through a cracked door to see the doctors observing my x-rays and was shocked at the sight of my spine. It looked like a writhing snake.

The doctors informed me I had scoliosis, or an abnormal curvature of the spine, which they measured to be roughly 20 degrees off base beginning at the lowest part of my spine. A few weeks later we visited a specialist and learned that the curve was actually more like 60 degrees and would require immediate surgery to correct.

In Baltimore at Johns Hopkins, I can remember lying on an operating table as a ring of masked faces peered down at me and a surgeon counted “3, 2, 1,” before my vision cut to black. While I was under they opened up my ribs, dislocated my vertebrae, stretched out my spine and fused it back together with bone grafts from my hip. A stainless steel rod was then screwed onto my spine to help stabilize it during healing. When I awoke the next morning I was alarmed to find that I couldn’t move my left leg. They had to sever a nerve during surgery and hadn’t told me in advance. Additionally, the pediatric ward that I was being kept in ran out of morphine, and I went without appropriate pain relief for hours on end. The pain felt like a supernova exploding throughout my body. The feeling carved a memory that I will never forget.

In the lead-up to surgery, the doctors prepared me for a lot. But they never told me I’d be dealing with chronic pain for the rest of my life. It was as if a Pandora’s box had been opened, providing insight into a wider American phenomenon.

Pain is notoriously difficult to measure, but there is no question that America is awash in it. Studies from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) put the number of people suffering from chronic pain at about 50 million, or 20 percent of the population. It remains unclear how the pandemic affected these numbers. Pain factors prominently in the opioid epidemic. It contributes to alcoholism, as well as other forms of addiction. Sometimes it leads to suicide. All of this radiates out to affect families and friends, neighborhoods and communities, and American society as a whole.

According to the British economist Angus Deaton, who became famous for coining the term “deaths of despair,” the landscape of American pain is developing in counterintuitive ways. It is commonly assumed that pain increases with age. But in America today, “the elderly report less pain than those in midlife,” he writes with Anne Case and Arthur Stone in a 2020 paper titled “Decoding the Mystery of American Pain Reveals a Warning for the Future.” “This is the mystery of American pain,” they note in regards to the unexpected findings on pain related to age. Another of their important findings is that “the gap in pain between the more and less educated has widened in each successive birth cohort.”

In my own experience, there probably was no way to avoid long-term pain, considering the trauma that was inflicted upon my trunk and spine—the superconductor of neural connectivity in the body. On top of that, the distortion wrought by scoliosis doesn’t just bend, it also twists, and this corkscrewing wasn’t totally fixed with the surgery. Worse still, now it was frozen in place.

As a result of my structural imbalance, I am forced to walk a very narrow path. If I don’t sleep well, get stressed, eat badly, or drink too much, I seize up with inflammation and the scoliotic pattern radiates outward into the rest of my body. I can feel the corkscrewing in my hips and shoulders, in my face and eyes, as if being trapped in a twisted straight jacket. As Quasimodo is described in The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, “The grimace was his face. Or rather, his whole person was a grimace.”

Then there is the emotional dimension. As pain researchers Ernest Volinn and John Loeser note in a 2022 paper on chronic back pain:

“The experience in its intense form has been compared to a nightmare: terrible things are happening to those undergoing it, worse are threatened; an inexplicable force is causing those things to happen, against which the will is helpless; and the experience goes on seemingly without end.”

When I was young I felt unstoppable. I wasn’t allowed to run or jump for a year after the operation, but I didn’t let it get me down. Soon enough I was back to playing basketball, lifting weights, and jogging. Whatever pain I had I simply blasted through, thankfully never becoming addicted to pills. This carried on until I left for college, and the Twin Towers fell during the first week of school, blowing up my slacker state of mind.

As the aughts wore on I grew increasingly depressed. You grow up, work more, sleep less, and deal with increasing levels of stress. The resiliency that I felt in high school began to fade as the pain creeped inside my brain. At the same time, late stage capitalism was weighing heavy. The 2000s proved to be an age of historic stress and instability, successive shocks to the system, political dismay among the populace, and spiraling inequality which the pandemic only exacerbated.

Some say that change is constant. There’s nothing new under the sun. But this downplays the level of historical backsliding that “geriatric millennials’’ like myself have borne witness to. Consider all that has befallen America beginning with 9/11 and leading up to the illegal invasion of Iraq: “Mission Accomplished” turned 20 years of war; Hurricane Katrina and grainy cell phone videos of African Americans being killed by cops or dying in floodwaters; criminal Wall Street negligence, the stock market crash of 2008, and the gall of “Too Big to Fail”; the election of Barack Obama, our first Black president, whose message of “Hope and Change” turned out to be just another corporate lie (consider his record on deportations or the prosecution of whistleblowers, his exponential expansion of Bush’s illegal wars and continuation of mass surveillance, the brutality of his drone strikes, his refusal to codify Roe v. Wade, his refusal to prosecute the bankers who destroyed our economy and caused millions to lose their homes). As Obama said of himself once: “My policies are so mainstream that if I had set the same policies … back in the 1980s, I would be considered a moderate Republican.”

Now add the pangs of climate change, the agony of the opioid epidemic, the horror of mass shootings and children being slaughtered at school. The middle class collapsed. Then, after decades of cratering faith in American public institutions, we got Donald Trump—a reality show host turned president—the shock of which was directly followed by COVID, a biblical plague that we have been told to “learn to live with” and which punctuates the slow-motion death of the American dream. No, this has not been a time like any other.

Furthermore, the “it’s always been this way” argument ignores how very strange this time has been with the advent of the Internet and the ubiquity of screen culture—on par with the development of the written word itself—which captures curated snippets from our struggles and streams them straight back into our collective conscience. While the Internet possesses incredible potential, so far its results do not seem promising regarding human development. On the one hand we are entering an era of unprecedented connection and globalized consciousness. On the other, a new Dark Age of the mind.

To what extent do we perpetuate our shitty modern reality by indulging in Big Information Overload? As the Thiền Buddhist monk and peace activist Thich Nhan Hanh once said, “water the flowers, not the weeds.” When we’re online, let’s face it, we tend to water the weeds. Whatever you focus on grows. You wanna fight Nazis? You wanna smash socialists? In some ways the left and right create each other. It’s phenomenology. Meanwhile, the ceaseless flow of smartphone media seems to tap the addiction centers in our brains and leads to negative impacts on our emotions. If we’re depressed, angry, anxious, or fearful, it can be easy to unload our feelings onto some enemy “other” in society.

Like chewing on a canker sore, we keep coming back for more. The incessant alerts allow us no stillness. Tribalism means we never lay down our guard and look for commonality. The tension and turbulence builds up in our system. And at the root of it all we live with pain, the grinding prosaic, and a concurrent inability to break our over-sensitized buzz.

But there is hope, for as the science of pain medicine shows, simply learning about how pain works can often prove half the battle.

According to a handy little book called Why Do I Hurt? A Patient Book About the Neuroscience of Pain: “Once pain patients become educated about the neuroscience of pain, they understand more about how danger messages are processed. Realizing that a lot of the pain they experience is due to extra sensitive nerves, their nerve sensitivity is actually turned down.”

It may sound crazy, but pain is entirely produced in the brain. Biologically speaking, when you stub your toe, it’s not pain that shoots up your leg, but a signal which travels through the nervous system up the spine to the brain, where it is evaluated, taking into account memory and context, to produce an appropriate protective response. This process is called nociception.

So in a way, pain is indeed in your head. But it’s real. Complicating matters, it can be highly subjective and often misread reality. Memory plays a crucial role. To illustrate this point, the Australian pain researcher Lorimer Moseley likes to tell a story about a time he was hiking in the bush and felt a prick on his leg. “The way I make sense of what happened to me,” he said in a TED Talk, “is that the brain thought: ‘Frontal lobe, have we been anywhere like this before?’ ‘Hang on, I’ll just ask the posterior parietal cortex: Have we been in this environment before?’ ‘Yes, we have.’ ‘Has it happened at this stage of the gait cycle?’ ‘Yes, it has.’ ‘Is it coming from the same location?’ ‘Yes, it is.’ ‘What is it?’ ‘Well your whole life growing up you used to scratch your legs on twigs. This is not Dangerous.’”

Moseley had been bitten by a deadly Eastern brown snake. But he kept walking and later fell unconscious from the venom’s toxic effect, barely surviving the incident. Six months later he felt another prick on his leg as he was walking outside; he collapsed on the ground screaming. This time around, his posterior parietal cortex reasoned: “‘Last time you were here you almost died and I’m going to make this hurt so much that you can do nothing else,’ and I was in absolute agony for what seemed like minutes. Screaming pain. Until one of my mates looked at my leg, and there was a little scratch from a twig.”

When pain becomes chronic, it can spread throughout your body. “In some people, the nerves that ‘wake up’ to alert you to the danger in your tissues calm down very slowly and remain elevated and ‘buzzing,’” according to Why Do I Hurt?. “If the alarm system in your house goes off, it probably wakes the neighbors right next to you,” it continues. “If the alarm system keeps going, some neighborhood down the street may also wake up. Nerves work the same way.” The growing cacophony of signals overwhelms the system and produces paranoia. “In this state, it does not take much activity, such as sitting, reaching, bending or driving, to get the nerves to fire off danger messages to the brain. The nerves become extra sensitive. … The main issue is increased nerve sensitivity.”

Further aggravating the situation, the body then sends immune molecules (which are designed to keep you healthy) to see if anything is wrong, which can make matters worse. Tellingly, the book likens these immune molecules to police officers going around from house to house knocking on doors to see what’s up. More often than not, this ends up doing more harm than good.

Another elusive aspect of pain is that it can exist without obvious physical damage to the body. Such is the case with much chronic pain, where the brain generates pain internally without any outside stimuli through a process known as “central sensitization.” In many ways chronic pain amounts to emotional pain. In my own experience, I saw how it could become synonymous with depression. Others develop chronic pain via emotional abuse which can dog them throughout life, especially when suffered as a child. Research has shown that adults who were abused as children can experience abdominal pain when there is no obvious physical cause.

“As human beings we belong to an extremely resilient species,” writes the psychologist Bessel van der Kolk in the groundbreaking study on trauma, The Body Keeps the Score:

“Since time immemorial we have rebounded from our relentless wars, countless disasters (both natural and manmade), and the violence and betrayal in our own lives. But traumatic experiences do leave traces, whether on a large scale (on our histories and cultures) or close to home, on our families, with dark secrets being imperceptibly passed down through generations.”

When trauma occurs—whether caused by physical injury, psychological abuse, exposure to war or systemic oppression—anger, depression, illness, and anxiety can follow. As van der Kolk notes, people react in different ways depending on the circumstances involved and the subject’s inborn biological traits. When triggered, Jack might freeze up, whereas Jill flies into a rage. Perhaps this explains some key aspect of our political free fall, with far-right candidates exploiting pockets of rage and defiance while simultaneously profiting from a broader sense of alienation and indifference felt amongst those who don’t see much use in voting.

Again and again, the role of memory proves crucial. As Sigmund Freud once remarked, “I think this man is suffering from memories.” As van der Kolk writes in The Body Keeps the Score, “When the alarm bell of the emotional brain keeps signaling that you are in danger, no amount of insight will silence it.”

In Trauma and Memory: Brain and Body in a Search for the Living Past, researcher Peter A. Levine writes about the difference between “normal” memories and traumatic ones. Regular, declarative memory is “ephemeral, ever shifting in shape and meaning,” he writes, “like a fragile house of cards, perched precariously upon the shifting sands of time, at the mercy of interpretation and confabulation.” It is something that we are able to consciously work with and reconstruct in a process that creates “cohesive narratives.” Traumatic memory, on the other hand, operates at the level of the unconscious and is experienced “as fragmented splinters of inchoate and indigestible sensations, emotions, images, smells, tastes, thoughts, and so on,” which afflict the body and mind in unexpected, deleterious ways. Without help, someone suffering from traumatic memory is essentially powerless to control what is happening to them.

This raises a question: at a time in which a broad sense of powerlessness is increasingly being shared amongst Americans, in relation to the environment, our politics, and the economy, how should we relate to one another? What we tend to have now is mutual intolerance and culture war hate, which only propels the status quo. What we need is radical acceptance and compassion.

To “radically accept” does not mean we should forgo our morals, accept bad politics, or ignore violence and oppression, but instead to recognize that hate is almost always born out of trauma and wounding, and that hating hate only begets more hate. As James Baldwin once wrote, “I imagine one of the reasons people cling to their hates so stubbornly is because they sense, once hate is gone, they will be forced to deal with pain.”

In the emergent field of psychedelic therapy—which has proven remarkably effective at treating addiction, depression, and other chronic conditions, while posing little to no addictive risk itself—a treatment modality known as Internal Family Systems [IFS] is increasingly being used to strengthen the benefits of a psychedelic trip. IFS operates on the assumption that there is no such thing as a unitary self, but instead that we are composed of a variety of “parts,” which exist in relation to each other. In essence, IFS proposes that we “contain multitudes,” to quote poet Walt Whitman. One “part” of you may feel like a loving parent, where another personifies your inner race car driver. In a healthy and secure place, these subpersonalities resonate and sing together, making us living embodiments of inner diversity. But when the body experiences trauma, certain “parts” can become frozen in time, or repressed, leading others to abandon their natural roles in an effort to protect or even shame the “exiled” parts. As a result, friction, imbalance, pain, and disharmony afflicts the entire system.

It is interesting to think about American trauma through the lens of Internal Family Systems, to consider the cultural narratives that scaffold our pain and the formative wounds that haunt the present day—many of which have largely been forgotten. If the collective American psyche took a heroic dose and reckoned with its history, good lord, who knows what would come out? A revolution? A protest? A giant comical fart?

But we aren’t ready for that. No, not even close. We haven’t even learned how to sit with ourselves and be quiet.

In some ways we are no more free than Pavlov’s dog. In others we can choose how to inform and condition our minds.

In his classic book The Four Agreements, the Mexican spiritualist Don Miguel Ruíz appeals to Toltec wisdom to argue that personal freedom can only be achieved by rooting out external forces of manipulation from the mind. Freedom means “being who we really are,” he says. Much of his work deals with the question of “domestication” (loosely, societal programming) and how it relates to our collective “dream of the world.” We can live a dream of heaven or a dream of hell, he says; it all depends on how we use our “word,” which is a form of “magic.” But from the Toltec point of view, “All humans who are domesticated are sick. They are sick because there is a parasite that controls the mind and controls the brain. The food for the parasite is the negative emotions that come from fear.”

Writing in 1997, Ruíz likens this parasite to a “computer virus.” He states: “When we see the world through a computer virus, it is easy to justify the cruelest behavior. What we don’t see is that misuse of our word is putting us deeper into hell.” Further developing this idea, Ruíz draws up the Toltec concept of Mitote, or “the chaos of a thousand different voices all trying to talk at once in the mind.” Mitote is similar to the Hindu concept of Maya, or the fog of perception, and it reminds me a great deal of the cumulative effect of screen culture.

Ruíz believes that we need to “rebel” against this virus of the mind, and suggests a couple ways of doing so. Likening the parasite “to a monster with a thousand heads,” each of which represents our fears, he says that “one solution is to attack the parasite head by head.” Conversely, a second and perhaps more straightforward approach would simply be to “stop feeding” it.

In my own experience, fasting taught me just how much food is like a drug, as is social media. Online there is an informative video lecture presented by cardiologist Pradip Jamnadas, who enumerates all the ways that fasting benefits your health, while pointing out that you never see it advertised. Somewhere in the lecture, he says, “I have nothing to sell you,” which really got me thinking.

Maybe one reason people think fasting is crazy is because it’s antithetical to the entire capitalist system. As a nation in pain we are sold pills for just about everything. “More than four in ten older adults take five or more prescription medications a day, tripling over the past two decades,” according to one 2019 study. “Nearly 20 percent take ten drugs or more.” Needless to say, this approach only treats symptoms and mires us in an overmedicated fog. In a world that is becoming less and less predictable, we desperately search for meaning and stability while being deluged by myths and narratives that distract us from the true nature of our chaos. As if Russian interference is to blame for our free fall. Or was it pedophilic Lizard People? These narratives are as cheap and fake as the pink slime that adulterates our fast food, and as toxic as the pills that get marketed as silver bullets for our pain.

Meanwhile, online algorithms and the harmful realities they create only give profit to the people at the top, who will fly off in rocket ships when the world finally goes up in flames. But what if the best way to break free from this collective mental stranglehold was to tune out corporate predatory media altogether?

Put down your smartphone. Question your screens. Go for a walk in the woods. Take a look at the leaves on the trees. Trauma or tragedy can live in the body. So can beauty and poetry. What matters most now is that we clear the fog of our pain so that we can come back to our senses, and begin to envision a better way of being.