We Are All Spartacus

Why has the story of Spartacus become important to leftists over the years? Because Spartacus showed what it would take for people to liberate themselves from violent systems of oppression.

When it comes to erecting monuments, the Left sometimes has a “statue problem.” As a political philosophy, leftism emphasizes and exalts the collective, whereas monuments are often made to individuals. There are abstract representations, such as the Worker and Kolkhoznitza Woman in Moscow, which depicts two people with a hammer and sickle. The choice to build monuments to archetypes does have the benefit of avoiding elevating problematic individuals whose statues have to be torn down once everyone realizes the kind of person they really were. (See, for example, the statue of slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol, which Black Lives Matter protesters tore down and threw into the Bristol Harbour. Glasgow had to take down its wooden statue of Sir Jimmy Savile, the once-beloved British television host who turned out to have been one of the country’s most prolific sexual predators.) When statues of leftists have been raised, they have often been part of a cult of personality (often installed by the one depicted). We do not need more giant heads of Marx and Lenin.

But if we want to identify a single individual emblematic of the struggle we wish to commemorate, we could hardly do better than Spartacus (c. 111–71 B.C.), who helped lead a slave uprising against the Roman Republic. A Thracian (Thrace encompassing parts of modern day Greece, Turkey, and Bulgaria), Spartacus was at once a heroic individual and a representative of the masses.

Spartacus is among the members of the pantheon of leftist heroes who lost their specific battle. In that respect, he keeps the company of the International Brigades (who fought against fascism in the Spanish Civil War, and lost), Rosa Luxemburg (who fought for democratic socialism and the nascent forces of fascism in Germany, and lost), and seemingly every candidate yours truly has backed for public office. As Francis Ambrose Ridley observed in his work Spartacus: A Study in Revolutionary History, “the names of the great revolutionary liberators and martyrs of humanity, from Spartacus to Rosa Luxemburg, who fell foremost in the age-long struggle to redeem their fellows from the yoke of capital, will shine forever down the ages.”

When others have sought to break their chains, Spartacus has frequently been invoked as a point of comparison. Toussaint Louverture, the Haitian revolutionary who was instrumental in the overthrow of French colonial rule, was described by his friend Étienne Laveaux as “the black Spartacus, the leader announced by Raynal to avenge the crimes perpetrated against his race.” Later, Fidel Castro would echo the comparison, saying that “at a time when Napoleon was imitating Caesar, and France resembled Rome, the soul of Spartacus was reborn in Toussaint Louverture.” (Sudhir Hazareesingh’s excellent book on Toussaint Louverture is also called Black Spartacus.)

In an 1861 letter to Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx dubbed Spartacus “the most splendid fellow in the whole of ancient history. Great general (no Garibaldi), noble character, real representative of the ancient proletariat.” Such was Spartacus’ standing in the leftist imagination that Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht’s “Spartacist League,” the Marxist Revolutionary group formed in post World War I Germany, was named after this Thracian from antiquity, rather than someone nearer to home. When delivering his lecture “The State,” Lenin praised the work of the Spartacist League and waxed lyrical about the illustrious history of their namesake: “For many years the seemingly omnipotent Roman Empire, which rested entirely on slavery, experienced the shocks and blows of a widespread uprising of slaves who armed and united to form a vast army under the leadership of Spartacus.” The struggle of Spartacus two millennia prior was both an inspiration for, and seeming evidence of, Marx and Engels’ claim in their 1848 Communist Manifesto that “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.”

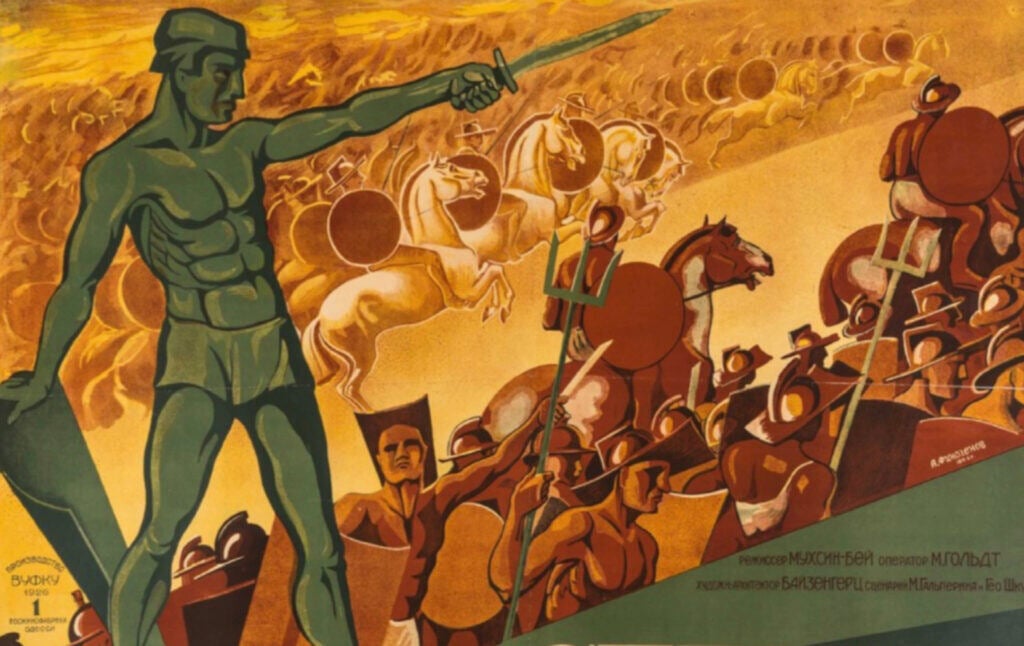

As the newly-formed Soviet Union cast its net for heroes running the whole gamut of history, they embraced Spartacus. For good or ill (Stalin was a fan), Spartacus enjoyed a high reputation. As Oleksii Rudenko’s “The Making of a Soviet Hero: The Case of Spartacus” shows, the figure of Spartacus was used in a number of different fashions in the USSR: as a revolutionary inspiration, as an exemplar of sporting prowess, and as historical precedent for the forces of socialism. “Spartacus” was introduced as a “socialist” male name for babies, resulting in several prominent Soviet citizens being called Spartacus. Several towns and cities in the USSR had streets named Spartakovskaya or Spartakivska. Ukraine still has a village called Spartak as well as a Spartak hotel. After the USSR declined to participate in the Olympics, it launched its own “socialist sport competitions” called Spartakiads.

The Soviets may have made special use of Spartacus, but his story has resonated more broadly. Spartacus has been depicted in film, television, ballet, and literature. Each portrayal is based on verifiable events, but while there are constants—depictions of slaves, gladiators, rebellions, and impeccably defined torsos— most depictions fail to retain the revolutionary zeal of the real Spartacus. We might well ask: beyond entertainment, how useful are these stories for the left? What can they teach us?

Let us first return to the story of the real-world Spartacus. Prior to achieving fame as a literary and cinematic character, Spartacus was featured in classical histories such as those of Plutarch (who was writing circa 100 C.E.) and Appian (who was writing circa 150 C.E.). Across sources, parts of the story remain consistent: Spartacus, having escaped a gladiator school, led a slave rebellion, and the slave army proceeded to roam Italy, defeating Roman armies that were sent to abate their advance (the disgrace of which was enough for the Romans to bring back decimation—the charming practice where one in ten soldiers were selected from across the legion to be executed by their peers—as a form of punishment for their soldiers). Finally, the insurrectionist force was defeated at the hands of the Roman general Crassus. Spartacus is said to have died in battle as he sought out Crassus himself. There is a striking juxtaposition here: the richest man in Rome (Crassus once declared that “no one was rich who could not support an army out of his substance”) being opposed by one who had nothing. It’s easy to see how Spartacus became idolized.

Over the years, Spartacus has indeed been fashioned into statuary. Nineteenth century French sculptor Denis Foyatier’s rendition depicts Spartacus breaking his chains while (in a theme which will become familiar) wearing naught but—well, if not a smile—a stern expression. Initially created for the aristocracy in 1827, with an opportunistic sleight of hand, Foyatier amended the date to July 29, 1830, for some intentional synergy with the Second French Revolution. The statue is an assertion of freedom and sexuality but otherwise says little.

In stark contrast to the immobile work of sculpture, Aram Khachaturian’s ballet “Spartacus” (1956) is a riotous depiction of unrest. It emphasizes the dynamism of revolution while retaining a love story at its heart. The ballet portrays a revolution which is almost permanently in motion and at its strongest when the revolutionaries are synchronized and complementary in their actions. The relationship between Spartacus and his wife Phrygia is as integral to the production as the slave revolt. It is perhaps the finest example of that all too often overlooked fact of revolution: that it is borne out of many individual acts of love whether they be for a partner, a child, or the fellow members of an oppressed group.

Howard Fast’s literary Spartacus (1951) is the mid-20th century wellspring from which subsequent Spartacus depictions appear to flow. It is an unapologetically revolutionary—even Marxist-Leninist—work written while the author was incarcerated for refusing to name fellow Communist Party members to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Fast is at pains to depict a revolution with a nascent vanguard party (in this case gladiators) who in turn lead the masses (comprised principally of slaves) against the ruling class and the established order. It concludes:

“A time would come when Rome would be torn down—not by the slaves alone, but by slaves and serfs and peasants and by free barbarians who joined with them. And so long as men labored, and other men took and used the fruit of those who labored, the name of Spartacus would be remembered, whispered sometimes and shouted loud and clear at other times.”

Christopher Hitchens, the patriarch of the problematic left (on the one hand, he was a long-standing socialist with a laudable body of work on subjects including Orwell and anti-imperialism, but on the other, he used to lash out at anyone who had the temerity to question the efficacy of the War on Terror), was well-acquainted with the works of Howard Fast, and when reviewing the author’s autobiography cited Spartacus as one of the tomes that “are still on many a shelf, and once set the blood coursing through the veins of men and women who are now safe, staid liberals.” Here Hitchens acknowledges the adrenaline rush that Fast’s Spartacus could instill, but also the way in which the fervor can subside and those that once proclaimed the revolution become that which they revolted against. (Hitchens does not, however, consider whether he himself might belong in the category.)

Fast’s work was adapted for the Kirk Douglas film Spartacus (1960), which stands as its own monument to the life of Spartacus and is one of the great “sword and sandal” epics from Hollywood’s golden age. Douglas’ was not the only attempt to commit the story to screen, as rival Hollywood star Yul Brynner was trying to make a film on the same subject at the same time, though he eventually yielded to Douglas’ production. The film was a triumph for Douglas and director Stanley Kubrick, becoming the highest-grossing film of the year and winning four Academy Awards. Douglas’ Spartacus became iconic, and since we lack a portrait of the real Spartacus, today when one tries to conjure up a mental image of Spartacus, it is hard not to think of Kirk Douglas.

Douglas devoted a significant portion of his autobiography (The Ragman’s Son) to the creation of Spartacus, and at age 95 wrote an entire book about the experience called I Am Spartacus!: Making a Film, Breaking The Blacklist. Douglas recounts the struggles of securing the rights and funding along with the matter of finding a workable script. For all his undoubted zeal, Howard Fast’s screenplay was, by a number of accounts, packed with more lectures than action. (“Dear God, it was awful—sixty pages of lifeless characters uttering leaden speeches,” Douglas writes in I Am Spartacus.)

Veteran screenwriter Dalton Trumbo was drafted to write a script worthy of the epic production. At the time Trumbo was on the Hollywood blacklist (one of the so-called “Unfriendly Ten”) as one of those who had defied HUAC, and had been imprisoned and fined for his refusal to “name names” of fellow “Reds.” Trumbo was working under a series of aliases (e.g., Felix Lutzkendorf, Robert Rich) or using other writers as “fronts,” the other writer taking the screen credit while Trumbo wrote the script. Hedda Hopper, a Hollywood columnist disdainful of suspected communists in the film industry, wrote of Spartacus that “that story was sold to Universal from a book written by a Commie and the screen script was written by a Commie.” Alas after threatening us all with a good time, Hopper concludes: “so don’t go to see it.”

Douglas felt an innate relationship with the figure of Spartacus due to the Douglas’ own Jewish heritage and identity. When gazing upon historical Egyptian structures he wrote: “I identify with them. As it says in the Torah: ‘Slaves were we unto Egypt.’ I come from a race of slaves. That would have been my family, me.” The story of Spartacus is able to transcend racial and ethnic lines because ultimately it is a story about the oppression of people via an iniquitous economic system. Slavery in all its forms is abhorrent, and those who endure it, either directly or within collective memory, can relate to Spartacus’ effort to end their oppression and destroy their oppressor.

Douglas’ Spartacus is somewhat taciturn at the outset but grows in oratory skill and confidence in step with his revolution. While he is always billed as defiant, at the outset he is not the leader of men. The breakout from the gladiator school is as exhilarating a depiction of non-hierarchical autonomous collective group dynamics (aka a crowd working as one) as you’ll see committed to celluloid. Anyone who has partaken in demonstrations that have seemingly moved as a single entity without the need to defer to an obvious leader or organizer will be familiar with the phenomenon.

When confronted with the news of the slave rebellion, the Roman Senate in Spartacus cannot accept that slaves would join voluntarily, instead pronouncing that “Around Capua they ravage the countryside forcing other slaves to join them. Looting, robbing, burning everything.” (From the civil rights movement to union organizing drives, uprisings are often blamed on “outside agitators,” the oppressed themselves being considered both too weak and too contented to possibly challenge their condition effectively.) When the Senators decide that sending in troops is the only way to deal with Spartacus et. al., one Senator feels the need to rise to his feet and declare: “I most strongly protest, there are more slaves in Rome than Romans. With the garrison absent, what is to prevent them from rising too?” The chant from contemporary anti-fascist demonstrations (variously directed at both the fascists and the cops), “There are many, many more of us than you,” held true even circa 70 B.C.

In Spartacus, the rebelling slaves force two Romans into ersatz gladiatorial combat in the same arena where Spartacus and fellow gladiator Draba (who is of African heritage) fought. Yet Spartacus stops the bout, asserting that he swore he would die before watching two men fight to the death for sport (a salutary lesson in the need for revolutionary movements not to become that which they revolted against in the first instance). “What are we, Crixus? What are we becoming? Romans?” As a socialist, I can still acknowledge the wisdom of the point that 19th century anarchist Mikhail Bakunin made when he said: “When the people are being beaten with a stick, they are not much happier if it is called ‘the People’s Stick.’” Instead of reproducing the worst features of the state apparatus, get yourself a Spartacus (as depicted by Kirk Douglas) who snaps fasces with his bare hands, accompanied with the words: “Tell them we want nothing from Rome. Nothing except our freedom.”

The film covers a lot of ground (with a runtime of 197 minutes it has plenty of room to do that) including the ostensible piety of the ruling elites: “I thought you had reservations about the gods.” / “Privately I believe in none of them and neither do you. Publicly? I believe in ‘em all!” There is also a somewhat patronizing gesture to the role of women in revolution. Spartacus observes of the slaves they have freed that there are “Too many women” to which he is rebuked, “What’s wrong with women? Where would you be now, you lout, without women who had fought all the pains of hell to bring you into the world?”

Spartacus also includes the following delicious exchange on the propensity of the ruling class to believe that the proletariat have no motivations, intelligence, or wit of their own, and thus anyone found to possess these qualities must not originate from the laboring class:

Pirate Leader

“I’ve heard that you are of noble birth yourself.”

Spartacus

“Son and grandson of slaves.”

Pirate Leader

“Of course, it pleases Roman vanity to think that you are noble. They shrink at the idea of fighting mere slaves.”

The elite cannot countenance the idea of fighting (or being bested by) workers who they view as being of an inferior rank. It is for this reason that they will focus on those in the movement who have some link with their conceptions of legitimacy (class, education, affiliation, etc.) and declare that the movement as a whole is being run by such people.

Ultimately, Spartacus and his army are defeated. The vanquished slaves are told that they are to be spared crucifixion if they give up Spartacus. Kirk Douglas’ Spartacus realizes the enormity of the situation and as he stands to sacrifice himself for the group, his comrade Antoninus beats him to the punch and declares, “I’m Spartacus,” only to be joined by a chorus of his fellows doing likewise. Spartacus weeps. The famous scene still has emotional power, despite having become a cliché and having launched numerous parodies of varying quality (from Monty Python’s sublime effort in Life of Brian through to a less than awe-inspiring Pepsi commercial featuring a Roman Centurion proffering a canned soda to Spartacus).

A common thread running through depictions of Spartacus has been the propensity for those crafting the works to seem somewhat, well, libidinous. The combination of gladiators being of a fabled virility, the raw masculinity of one-to-one combat, and Rome’s famed decadent licentiousness all seem to be at the forefront of writers’ and artists’ minds when adapting the story. Depictions of Spartacus, it must be acknowledged, more often than not seem horny for Spartacus.

In a scene initially cut from the theatrical release, 1960’s Spartacus featured a scantily clad Tony Curtis washing Larry Olivier’s back, with suggestive dialogue. (Antoninus tells Crassus he eats oysters but not snails, while Crassus tells Antoninus “My taste includes both snails and oysters.”) The scene was deemed too damned sexy for Eisenhower’s America—that is, the National Legion of Decency vetoed it. Still, when we see gladiatorial bouts, it’s not with the more heavily armored fighters. It’s underwear and rippling biceps all round, although the lack of clothing on the retiarius (a type of lightly equipped gladiator armed with a trident and net, styled to look like a fisherman) is historically accurate. Spartacus also finds time to show us a nude Jean Simmons, concealed by naught but a tasteful frond—the Hays Code, prohibiting depiction of “the more intimate parts of the human body,” protected her dignity.

The Starz television production Spartacus (2010-2013) is untroubled by The Hays Code, or seemingly any other code. It has a free and easy, equal-opportunity approach to nudity and sexuality. A television series has more time to go into the mechanics of revolution (the brewing of discontent, the acquisition of weaponry, and the steeling of resolve) but Starz’s Spartacus also uses the time to show John Hannah striding around, often in the buff, having a whale of a time. This Spartacus features such a plethora of sex scenes that it seems gratuitous even for the Starz network (which has given us racy fare such as Outlander and Da Vinci’s Demons).

So where stands the legacy of Spartacus? Does he remain crucified on the Appian way of capitalist exploitation? Does he stand alone in the arena, assailed by his many varied representations? We can see why Spartacus became a specifically leftist hero, with even the American depiction of him produced by communists. Spartacus was too much the violent revolutionary to become a liberal hero. The story of Spartacus is an inspiration to the oppressed, because he showed what it meant to be truly liberated and defiant. He directed violence against a cruelly violent system.

The spirit of Spartacus is still alive. It exists in every person building collective action in Amazon, Starbucks, and beyond: the union activist who defies the boss and organizes their workplace, the political representative who stands steadfast in their advocacy of basic healthcare against pressure groups, and all those who campaign for true equality and justice. There is a proud kith of all those who struggle against the status quo and seek revolutionary change, and together they utter with one voice echoing across the centuries: “I’m Spartacus!”