Hostile Architecture Is Evil and Should Be Banned

Attacking homeless people with spikes is morally tantamount to assault. Designers should not be permitted to incorporate the threat of pain into the built environment.

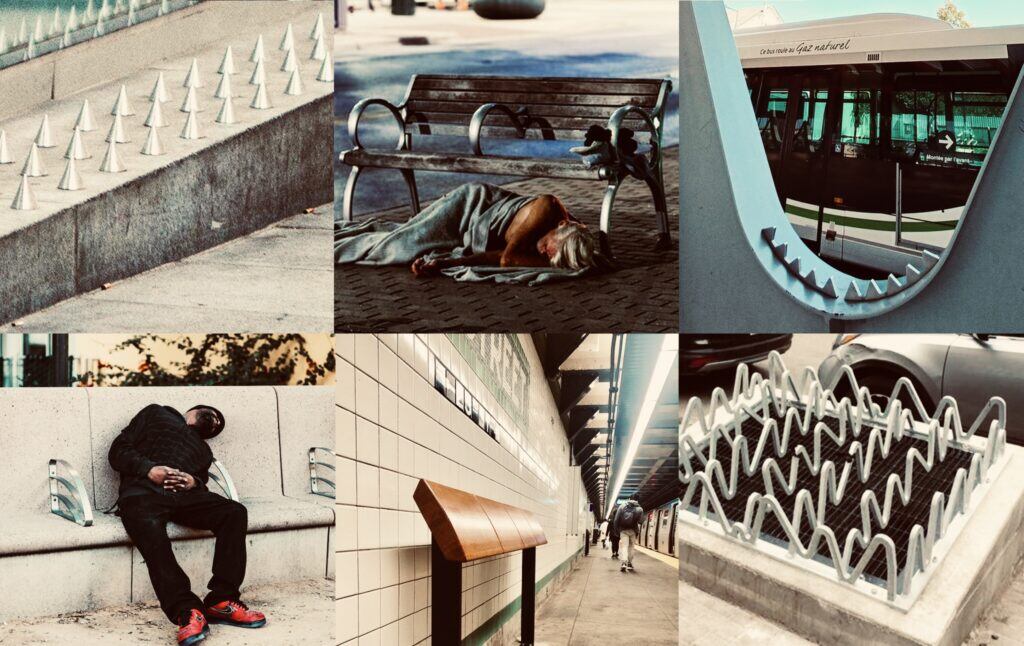

I am sure that if you have been in a city, you have encountered hostile architecture.1 Some park benches have an extra armrest in the middle so that you can’t lie down. Some are wiggly, or tubular, or slanted, or have a piece missing, or have uncomfortable bumps, in order to achieve the same effect. Some you can’t sit on at all—see the famous “leaning” bench of New York City. The goal is for anyone who tries to sleep to be put in physical pain or extreme discomfort. Essentially, the bench purposely attacks you if you make unauthorized use of it.

There are other examples. Random spikes and bolts. Clusters of poles, big rocks. Fire hydrants with little jagged cages over them so that you get poked in the ass if you dare to sit on one. Gaps in awnings so that it rains on you if you try to take shelter under it. In New York, “privately owned public spaces” (outdoor spaces that should be public but aren’t) are filled with “an array of spikes, bars, railings and other obstructions on benches and ledges.” In Japan, there is apparently at least one place where the floor itself will lift up and dump you off it if you try to sleep there. Even birds have been subjected to hostile design—see this tree full of “pigeon spikes.” (As a protest/parody of the way the poor are discriminated against in design, a German designer once produced a “pay and sit” bench that drives spikes into your butt if you don’t keep feeding it quarters.)

There are also less subtle means of menacing the homeless, such as playing loud music or intolerable high-pitched sounds, or spraying them with water (as the Strand Bookstore in New York was reported to have done in 2013). Because these measures do nothing to actually reduce homelessness, but instead just make it even more difficult to find a place to sleep, we see one of the more tragic scenes of our time: people trying to find a way to sleep amid the uncomfortable boulders placed beneath a bridge.

You can’t find many people who will publicly defend this stuff. There are dozens of articles from the last few years condemning it. Even Boris Johnson came out against anti-homeless spikes in London and public pressure caused a British supermarket to remove them. There is something so obviously dystopian about these measures that it’s easy to get people to hate them. (I certainly find it easy to despise the designer quoted by CNN who created the “serpentine bench”—the wiggly one—and says one of its “marketing points” is that it can “deter rough sleepers,” although he also points out that city governments ask designers to come up with benches that can’t be slept on.)

There are ways that people can take direct action against these inhuman design features. In Cambridge, Massachusetts, last year a heroic group conducted civil disobedience by removing the middle armrest from a number of benches. A Frenchman did the same thing in the city of Lyon in 2018. For those who prefer slightly less risky misdemeanors, you can buy a set of stickers to put on these features to call attention to them as a “design against humanity.”

Certainly, it’s good to have people out there taking the third armrest off park benches and forcing others to pay attention to the ways in which designers have found ways to make being homeless more painful. But of course, we ultimately need to have these features abolished. I think designers have an ethical responsibility to refuse to create anything that is meant to inflict pain on homeless people for attempting to go to sleep. That seems to me as basic as the moral obligation not to commit offensive violence against anyone. Fights over hostile design occur at the local level and can be won by committed activists.

In fact, in some ways the fight against obvious hostile design should be the most easily winnable, because the designs are so cruel that removing them would be so easy. One problem is that some hostile design choices aren’t obvious. Rather than the presence of a poky or knobbly thing that gets in your way, these designs exist as an absence—a failure to provide benches or bathrooms (why shouldn’t we be able to pee for free?) or shady places. “Ghost amenities” are the water fountains and picnic tables that aren’t in a space because those in charge of it have decided that any place fit for human beings will be fit for the homeless. It is no good just removing the spikes if we still have desolate public spaces where nobody can rest. The failure to build public space at all is also hostile, because it means that only the rich will have comfy places to go.

Hostile design doesn’t just punish its intended victims, but ends up hurting everyone. There have been times when I’ve wanted to lie down on a bench and couldn’t because of the wretched third bar, and one reason I find visiting New York City so stressful is because there’s hardly anywhere to sit down unless you go to a cafe and buy something. Of course, the elderly and disabled suffer the most—there is nothing more “ableist” than making a public space that physically punishes the need to stop and rest your body. And if you make your spikes jagged enough, they’re an injury risk to everyone, not just would-be nappers.

Because we have collectively decided that we do not believe in a “right to housing,” and will not provide free houses to the unhoused, many cities have large homeless populations. (When you do give free housing, the problem of having a population of people without housing—miraculously—substantially diminishes.) The rich dislike being around homeless people— “I shouldn’t have to see the pain, struggle, and despair of homeless people to and from my way to work every day,” wrote one San Francisco software developer, surely speaking for many among the city’s bourgeoisie. But if you’re unwilling to shell out money to actually give people housing, yet still feel it’s your right not to encounter poor people, the available alternatives are cruel: criminalize their existence, make them sleep on spikes, etc.

We should be able to agree as an absolute matter that deliberately hurting people who don’t have a place to sleep is monstrous. Spokes, bolts, etc. are all inhuman, and park benches should be comfy to take naps on. We need public spaces that welcome people and take care of their needs. If that results in places being full of people who don’t have a place to sleep, well, we have a choice between ruining the public spaces with hostile design or simply taking care of everyone compassionately and treating universal design (making places that meet everyone’s needs) as a nonnegotiable first principle. The real challenge is to build compassion and care into every space, but in the interim, we can at least get rid of the features that directly physically assault the poor, tired, and ill.

Euphemistically called “defensive” architecture, just as the Department of War was replaced with the Department of Defense ↩