Entering the Twilight Zone

Even though television is a highly commercialized art form, The Twilight Zone still managed to offer innovation and politically incisive commentary.

Despite the near-constant refrain that this or that season of television is really more like a “ten-hour movie,” the birth of TV as a medium is tied much closer to radio than cinema. Genres that developed on the radio jumped to TV, from sitcoms to soap operas and game shows to police procedurals. Like radio, early television drama was broadcast live, often performed twice, once for the East Coast and again for the West Coast. “Like a child in hand-me-down clothes, television inherited the best and worst that radio had to offer, from the Ed Wynns and Jack Bennys, who made millions of Americans laugh every week, to the blatant commercialism that drove the system,” Jeff Kisseloff writes in the introduction to The Box, his oral history of early TV. “Television did it all, but radio did it first.”

Long before he created The Twilight Zone, Rod Serling grew up a radio fanatic. Radio was, naturally, where he started his writing career. After returning from World War II with a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star, he had night terrors that would plague him for the rest of his life. He had enlisted the day after his high school graduation, becoming a paratrooper despite being, at five foot four, under regulation height. Only one in three men in Serling’s regiment survived. He witnessed a close friend being decapitated by a falling food crate and came within an inch of dying himself when a Japanese soldier pointed a rifle at him at close range. Despite sustaining a knee injury in battle that would plague him for the rest of his life, he had not been medically evacuated. “What I vividly recall is my dad having nightmares, and in the morning I would ask him what happened,” his daughter Anne later said. “And he would say he dreamed the Japanese were coming at him.” Writing stories and radio scripts became his outlet: “I was bitter about everything and at loose ends when I got out of the service,” he said. “I think I turned to writing to get it off my chest.” While going to college with his GI Bill educational benefits and disability payments, he submitted freelance radio scripts everywhere he could, ran the college radio station, and had a paid internship at WNYC in New York. After graduating, he worked as a radio staff writer and continued submitting freelance scripts. A script he wrote about boxing “would be far better for sight than for sound only, because in any radio presentation, the fights are not seen,” Martin Horrell told him when rejecting it in 1949. “Perhaps this is a baby you should try on some of the producers of television shows.”

He did start trying his babies on TV producers—and eventually made a name for himself writing episodes of anthology programs like Playhouse 90 or Kraft Television Theatre, plays-on-TV beamed right into your living room. This was the period once denoted by the phrase “Golden Age of Television”: Americans saw Twelve Angry Men as a live episode of Studio One on CBS three years before Sidney Lumet made it into a film with Henry Fonda; Paddy Chayefsky wrote Marty as an episode of The Philco Television Playhouse two years before the film version would win both Best Picture and the Palme d’Or. But Serling was frequently frustrated by censorship from both networks and sponsors. This ranged from the annoyingly silly—the line “Got a match?” was deleted from his TV play “Requiem for a Heavyweight” because Ronson lighters was a sponsor—to the grotesque, like his foiled attempts to write a script inspired by the murder of 14-year-old Black boy Emmett Till in Mississippi.

The first time Serling tried to address Till’s murder, he pre-censored himself by focusing his script on the lynching of a Jewish man in the South, rather than a Black boy. But when he let it slip in an interview that the script was inspired by Emmett Till’s murder, thousands of angry letters from white supremacist organizations and garden-variety racists poured in. ABC capitulated, and when the episode aired, no ethnicities were mentioned, the action was moved to New England, and, in Serling’s words, the killer was portrayed as “just a good, decent, American boy momentarily gone wrong.” Serling was devastated, writing to a friend, “I felt like I got run over by a truck and then it back[ed] up to finish the job.” His second attempt to write about Till’s murder—the Playhouse 90 episode “A Town Has Turned to Dust”—was more successful, though far from what he’d wanted, with the victim changed from Black to Mexican and the setting moved from the contemporary 1950s to the 19th century.

“I think it’s criminal that we are not permitted to make dramatic note of social evils as they exist,” Serling said in 1959. Though he described himself as a “moderate liberal whose roots go deep into the American soil, pounded there by immigrant parents who fed Eastern Europe during the nineteenth century,” Serling was passionately opposed to the Vietnam War and war in general, strongly egalitarian and pro-civil rights, and “subscribe[d] to and support[ed]” the goals of the New Left, endorsing Eugene McCarthy’s presidential run in 1968. That peculiar mix of Greatest Generation emotional belief in America’s alleged values and 1960s counterculture’s clear-eyed rage at all the horrors committed in America’s name could lend his writing a sticky in-betweenness. But at his best, Serling’s writing seems to see beyond the generational clash into something bigger.

Eventually, Serling hit on two ways to get around the censors. One was science fiction, which allowed him to write allegorical political stories that drew less censorious ire. “In retrospect, I probably would have had a much more adult play had I made it science fiction, put it in the year 2057, and peopled the Senate with robots,” Serling said about one of his censor-butchered scripts. “This would probably have been more reasonable and no less dramatically incisive.” The second was to make his own damn show, one over which he would have creative control. He called it The Twilight Zone.

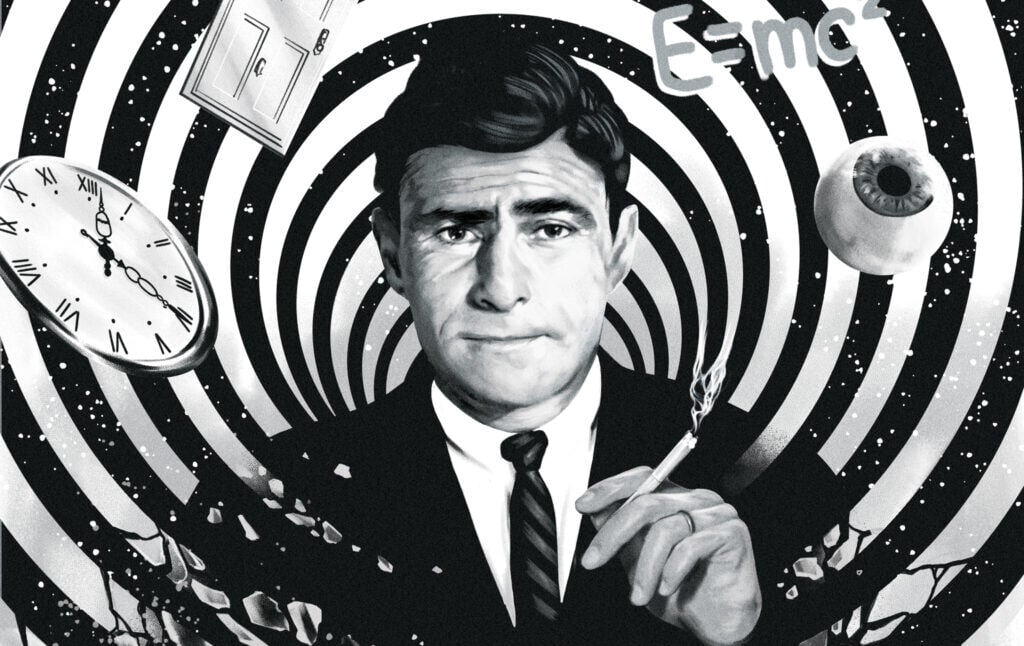

I grew up with The Twilight Zone the way most millennials did, the same way I was exposed to most of human culture: through the medium of Simpsons parodies. The Treehouse of Horror episodes of The Simpsons usually had segments parodying classic works of sci-fi and horror, from Edgar Allan Poe to Stephen King—and more than anything, episodes of the original Twilight Zone series. By the time I finally saw The Twilight Zone, so much of it (its plots, its aesthetics, the rhythms of Rod Serling’s narration) felt warmly familiar, almost nostalgic. Serling’s jaw is tight, and his mouth hardly moves, his deep voice resonating from his nose, a cigarette clutched in his hand: he has a tale to submit for your approval, one that takes place in “a fifth dimension, beyond that which is known to man … a dimension not only of sight and sound, but of mind … a land of both shadow and substance, of things and ideas.” It might be on a distant planet, a future dystopia, an ordinary street, or the old West. Everything might seem perfectly ordinary—until it doesn’t. Everything might seem strange, until a twist ending reveals what was happening all along. They’re stories, as Rolling Stone put it, “about everyday people thrust into extraordinary circumstances, folks who find themselves stuck in (and running out of) time, and dreamers who learn that every granted wish comes with a price tag.” It’s a show I knew as easy as breathing, collaged from parodies and homages and the thousand times somebody had said, “It’s like something out of The Twilight Zone.”

With those kinds of endlessly referenced cultural touchstones, sometimes the impact of the original feels blunted—like seeing Hamlet as full of clichés. But in The Twilight Zone, the familiar is made strange: sharp, fresh, and frequently unsettling, it feels endlessly relevant. Not—or not just—in its approach to universal human themes, but in how it deals with issues that we’re still dealing with today: war, capitalism, bigotry, the moral implications of technology, and the ever-precarious tightrope between conspiracy and paranoia. The Twilight Zone remains one of the most incisive works of art about life in the age of American imperialism.

An anthology show, The Twilight Zone’s episodes each work as standalones. Though the series forms a coherent whole in a way that 1950s anthology TV plays like Playhouse 90 never attempted, it can be hard to describe what, if anything, is The Twilight Zone’s premise. Like its contemporary Alfred Hitchcock Presents, its episodes are united in a combination of tones, tropes, and themes, less like a premise for a show than setting out a genre all its own. But where Alfred Hitchcock Presents brought the Hitchcockian stylings developed over decades of the director’s film career to the small screen, The Twilight Zone was inventing something more or less from whole cloth. It’s a sci-fi show, but not always. Sometimes it’s set in something approximating the real world: in “The Silence,” one man bets another that he can’t go an entire year without speaking—which he does, only by severing his vocal cords. In “The Fever,” a trip to Vegas takes a dark turn when a slot machine calls a man’s name and stalks him to his hotel room, and it feels like a look inside the internal struggle of an addict more than anything supernatural. Often the show goes beyond science fiction into fantasy: plenty of episodes feature magical wishes, premonitions, or the devil himself. It frequently delves into horror (sometimes drawing in part from Serling’s night terrors) but is no stranger to comedy or straight drama. “The Night of the Meek” features a Santa Claus origin story as delightful and charming as any half-hour of television you’ll see. The show loves to do social or political allegory, but makes room for just telling spooky stories, too.

When I try to fit The Twilight Zone into a genre box, I am reminded of Dr Pepper. Ask someone to describe the taste of Dr Pepper, and they can’t, not really. Dr Pepper and its knockoffs have been described in copyright courts as “pepper sodas,” not because they contain any pepper—they don’t—but because the only reference point to describe its not-quite-cola taste is the original soda. There’s no other way to capture what makes it not a Coke. By a similar logic, The Twilight Zone is—like Jordan Peele’s Get Out and Us, like Black Mirror, like about half of all twist endings ever since—quite simply, a Twilight Zone.

In addition to hosting the show and writing or co-writing 92 episodes of the series across five years, Serling brought on screenwriters with more experience in science fiction—most importantly, Charles Beaumont and Richard Matheson. In addition to writing great sci-fi and horror short stories—many of which were adapted into Twilight Zone episodes—both Beaumont and Matheson wrote screenplays for B-movie king Roger Corman, including for his series of Edgar Allan Poe adaptations. If you watch something like The Intruder, written by Beaumont and directed by Corman, in which a white supremacist (William Shatner, using his Captain Kirk speech-delivery powers for evil) arrives in a small Southern town to incite the white townspeople to violently oppose integration, you instantly sense why he’d be one of Serling’s first calls. The Twilight Zone is usually talked about as Serling’s baby, and that’s fair. But—especially in the show’s first years, prior to Beaumont’s illness—it feels like a three-man operation, with Serling as fearless leader. Watch enough and you can feel the rhythms each works in, and know whether Rod or Chuck or Dick is going to pop up in the “written by” credit at the end of the show. Dick Matheson episodes are clockwork-clever plotted sci-fi. Charles Beaumont leans more horror, even gothic, with a more political edge. Rod Serling, naturally, traverses the genres and styles that exist within The Twilight Zone, at once writing the show’s most political episodes and its silliest.

Season One’s “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street” is an episode that could only make it onto television in 1960 through science fiction, single-handedly vindicating Serling’s ambition. A perfectly ordinary street in suburbia—“a tree lined little world of front porch gliders, barbecues, the laughter of children, and the bell of an ice cream vendor,” Serling says in his opening narration—has a power outage. The residents gather out on the street, seeing if anyone knows what’s going on. One of the neighbors, Pete—hammer slung in his overalls—says he’ll go to the next street over to see if they’re affected, too. While he’s gone, a little boy called Tommy starts talking about how similar this is to a story he read about alien invasion. In the story, aliens disguised as a human family acted as scouts, and the power going out was their moment to strike. The adults initially dismiss Tommy and his childish ramblings, but the idea burrows its way in, festering.

When Les’s car mysteriously starts by itself, the neighbors point out that Les didn’t participate in the initial speculation about what caused the outage. And hasn’t he always been kind of a strange guy? Haven’t I seen him, late at night, staring up at the stars—almost like he was waiting for something? Wait, remember when Steve built a ham radio: why has no one ever seen it? Is he using it to talk to the aliens? (Steve sarcastically confirms that yes, he’s been talking to aliens on his ham radio, which goes about as well as you’d expect.) Accusations start flying hard and fast in every direction. Any idiosyncratic behavior becomes evidence of the extraterrestrial, and that there is an extraterrestrial hidden among them becomes unquestionable. A shadowy figure, hammer visible, approaches—the monster, Tommy says. So a man called Charlie shoots him. It was, of course, Pete, returned from the next street over, now dead.

It should be the moment that the suspicions they’ve let themselves run away with give way to cold, hard reality. But instead, suspicion turns on Charlie. What if Pete knew Charlie was the monster, and he killed Charlie to cover his tracks? The neighbors start pelting him and his home with stones. Terrified, he defects suspicion onto Tommy: isn’t it something that he “knew” about the aliens from the beginning? Instead of Pete’s death sobering the crowd, they end up in a full-scale riot.

It is a very, very obvious allegory for McCarthyism and the Red Scare. Because of television’s reliance on advertising revenue, the Red Scare was even more effective there than it was in the film industry. This is the origin of TV’s reputation for conservatism. “Anticommunist groups could get quick results by threatening to organize boycotts of the goods produced by the sponsor of a show that employed a ‘blacklisted’ individual, whether a performer or a member of the production staff,” Robert J. Tompson explains. Lucille Ball managed to wriggle out of being blacklisted by claiming her past affiliation with the Communist Party was insincere and at her socialist grandfather’s insistence. “The only thing red about Lucy is her hair,” Ball’s husband, co-star, and business partner Desi Arnaz quipped, “and even that is not legitimate.” When Hazel Scott, one of the first Black people to host an American TV show, was named in an anti-communist pamphlet, she wasn’t so lucky, and her show was immediately canceled. Making a non-allegorical TV episode about the Red Scare in 1960 would have been completely impossible. But “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street” doesn’t feel cautious. We know Serling turned to sci-fi to throw censors off his scent, but nothing in “Maple Street” feels like its allegory was born out of a wish not to be found out. At once a cousin to 1970s paranoia thrillers and Star Trek episodes that use future alien societies to comment on the present, human one, it pulls no punches. “There are weapons that are simply thoughts, attitudes, prejudices, to be found only in the minds of men,” Serling says in his closing narration. In a way Tommy is right: there are monsters living amongst the ordinary residents of Maple Street. But they’re not aliens. They’re horribly, terrifyingly human.

“For the record, prejudices can kill, and suspicion can destroy, and a thoughtless, frightened search for a scapegoat has a fallout all of its own—for the children and the children yet unborn,” Serling continues. “And the pity of it is that these things cannot be confined to the Twilight Zone.”

While The Twilight Zone’s politics always felt directly tied to its historical moment the way “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street” is—to all the hope and horror of the Kennedy era—what’s fascinating is how often it remains vivid and urgent in our own time. War, and especially the specter of nuclear war, is a constant on The Twilight Zone, from the H-bomb that leaves Burgess Meredith the last man on earth in “Time Enough at Last” to the strange glow a lieutenant serving in the Second World War can see around the men who are about to die in “The Purple Testament.” “A Quality of Mercy”—in which an American soldier in World War II temporarily becomes a soldier in the Japanese Imperial Army— has a degree of empathy for the Japanese that’s still rare in America and was practically nonexistent in 1961. War in The Twilight Zone is ever present and terrifying, leaving individual lives and the fate of the whole world on a knife’s edge. In “The Shelter,” the friendships of families living on the same street are torn apart when a nuclear attack is announced to be imminent and only one family has a fallout shelter. In “Third Rock from the Sun,” scientists flee their nuclear-war-torn planet—and in the episode’s final twist, we find out that the new planet they’ve escaped to is called Earth. The threat of the nuclear bomb was a core part of the public imagination in the “duck and cover” era, but it doesn’t feel antique. The threat shapeshifts and slithers, from the Cold War going nuclear to the War on Terror to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but the core anxiety remains.

Its consistent anti-war stance fts into a broader theme in The Twilight Zone: a preoccupation with inhumanity, inequality, and attacks on human freedom. In a speech at Moorpark College in 1968, Serling praised young people for their skepticism of “the war, the draft, deeply embedded social inequality and the worship of anachronisms which have become more ritualistic than real.” These were Serling’s themes, too. In “Eye of the Beholder,” a woman’s face is wrapped entirely in bandages as she recovers from her eleventh procedure to correct her hideous deformity and make her look “normal.” When the bandages are removed, the doctor intones that the procedure was a failure and there has been no change to her face—just as we see that the woman is conventionally beautiful. It’s then revealed that the doctors, nurses, and everyone else in this society has a pig’s snout for a nose. Because of the procedure’s failure, the woman is going to be exiled to a place where she’ll be among her “own kind.” The state’s pig-snouted leader gives a speech on television about the need for greater conformity. It is, rightly, one of the most iconic twists in a show full of them. It’s also one of the richest. At the simplest level, it’s a reminder—one that never goes astray—of the fundamental arbitrariness of beauty standards. But it also makes the case for noticing the fundamental arbitrariness of so many of the features around which humans base their prejudices, how diversity is so often treated as dangerous nonconformity. Just because a certain group of people are in the majority, that doesn’t mean everyone else is defective.

The Twilight Zone’s cynicism toward state-sanctioned conformity feels like a reaction to the 1950s and a prelude to 1960s counterculture all at once. In “The Obsolete Man,” Burgess Meredith plays Romney Wordsworth, put on trial in a future totalitarian state for obsolescence. He’s a librarian, which is punishable by death. The state has eliminated books. Further, Wordsworth believes in God, despite the state having proven God doesn’t exist. The Chancellor finds him guilty, but grants Wordsworth’s requests that he be allowed to keep his chosen method of execution secret, and for his execution to be broadcast on television. (The former is highly unorthodox; the latter is standard practice.) The Chancellor visits Wordsworth in his final hour, when Wordworth reveals he has chosen to die via a bomb—and that he has locked the door. The Chancellor begs for his life, in the name of God, and Wordsworth lets him go. His subordinates see the broadcast, and the Chancellor himself is found obsolete and killed. The God stuff feels a little weak: I could imagine it striking a contemporary viewer as akin to the weird anti-secularism parables of Pure Flix, the evangelical film production company behind God’s Not Dead, rather than the real-world state-atheist totalitarian regimes it’s trying to evoke. But Rod drives the point home when he, unusually, appears on-screen for his final narration:

“The chancellor, the late chancellor, was only partly correct. He was obsolete. But so is the State, the entity he worshiped. Any state, any entity, any ideology which fails to recognize the worth, the dignity, the rights of Man … that state is obsolete. A case to be filed under “M” for “Mankind”—in The Twilight Zone.”

Included in the original script, but not making it to broadcast, was the line, “Any state, entity, or ideology becomes obsolete when it stockpiles the wrong weapons; when it captures territories, but not minds; when it enslaves millions, but convinces nobody. When it is naked, yet puts on armor and calls it faith, while in the Eyes of God it has no faith at all.”

Serling died at the age of 50 from a heart attack. Of his two major collaborators on The Twilight Zone, Richard Matheson died in his sleep as an old man and Charles Beaumont died at just 38, after suffering from a mysterious brain disease that aged him rapidly. His son said he “looked 95 and was, in fact, 95 by every calendar except the one on your watch.”

There have been many attempts to revive The Twilight Zone since Serling’s original series, none particularly successful or acclaimed. Hollywood, as always, learns the wrong lessons, treating the show as another valuable property to exploit, missing what made it great. Gene Roddenberry, creator of Star Trek, once said: “No one could know Serling, or view or read his work, without recognizing his deep affection for humanity and his determination to enlarge our horizons by giving us a better understanding of ourselves.”

As Kisseloff explained, TV, in its origins from radio, is nakedly commercial—maybe the most commercial of any art form, and certainly the most corporate. But I have always loved television. Raised on a steady diet of sitcoms, soap operas, quiz shows, and cartoons, I was the kind of kid adults despaired about getting square eyes. The Twilight Zone reminds me how great television can be. Even this corporate, commercial, censorious medium can be an outlet for great, innovative, and politically incisive artists like Serling.