Aviva Chomsky on why “Science isn’t Enough” to Address Climate Change

Questions of justice and morality need to be at the center of our climate strategy because science can’t fix the climate problem, Chomsky argues.

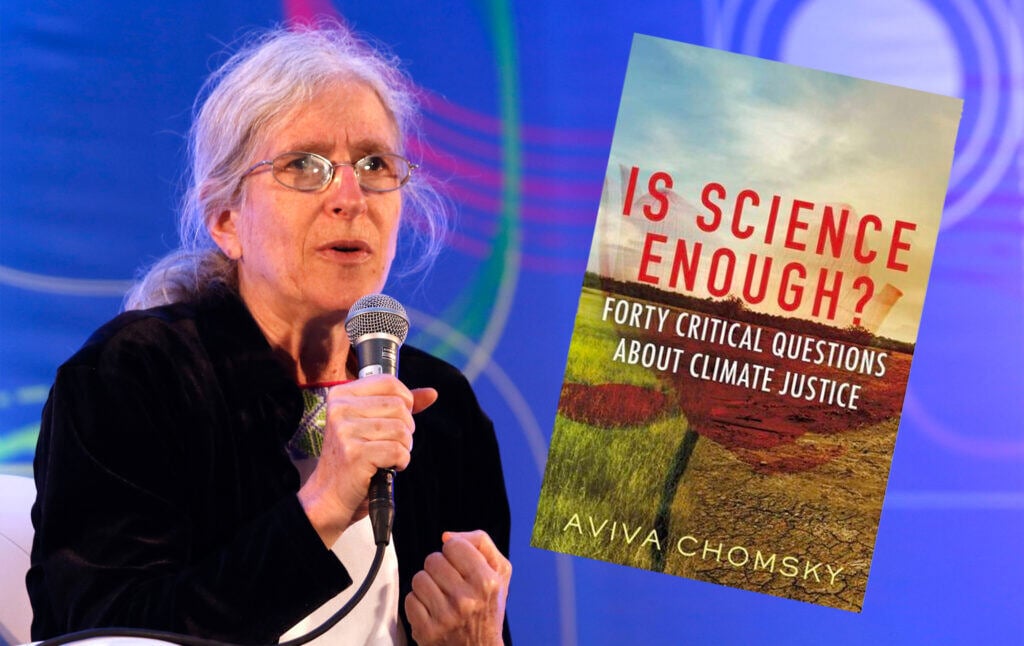

Prof. Aviva Chomsky teaches history and Latin American studies at Salem State University and has authored and edited numerous books including Central America’s Forgotten History, A History of the Cuban Revolution, and Undocumented: How Immigration Became Illegal. Her latest book Is Science Enough? Forty Critical Questions About Climate Justice tries to answer, in a clear and accessible way, the questions about what we ought to do to deal with the climate catastrophe. Is Science Enough? is a useful primer for anyone who wants to go beyond the facts of IPCC reports and think seriously about the choices we now face. It’s a book grounded in a desire to give people the practical knowledge they will need to take action. (It also answers the question of whether driving a Prius does anyone any good.) She came on the Current Affairs podcast to talk with editor-in-chief Nathan J. Robinson about the question of justice and the political and economic changes that will be necessary to prevent the worst suffering from climate change. This interview has been edited and condensed for grammar and clarity.

Robinson

Let’s start with the title question of your book: is science enough? Your book is a primer on climate change policy and some of the moral and justice-related questions around climate. The question of whether science is “enough” is really interesting. You begin by saying, Let’s assume we all agree on the basics of climate science. There are other books that make the case for the facts of climate change. People can be terrified by IPCC reports. But then you say, Okay, once we have that baseline of settled science, more questions arise. When you ask, “is science enough?”, what are the kinds of questions that you’re interested in?

Chomsky

I think much of the debate has been derailed by the far right position of science denialism. People concerned about climate change have been forced into this debate. What we’re doing is trying to defend the science and say that, yes, climate change is actually happening. And it’s actually catastrophic. And it’s caused by humans.

We’ve gotten so fixated on the debate as defined by the right that we’ve lost some of the narrative. We need to do more than defend science. Science is not going to bring us the solutions to climate change. The over-emphasis on science pushes us into a kind of technocratic position. Well, the experts are going to solve it for us. But the experts are not going to solve it for us.

The actual causes of climate change, I argue, are not just technical. And the solutions are not technical. Rather, they’re in our global economic system. Of course, the left wants to challenge the global economic system, but we need to make the case that the cause of climate change is colonialism, racism, and capitalism. Yes, the cause of climate change is CO2 emissions. But that doesn’t get us very far. We need to understand what it is about our political, social, and economic systems that keeps us on this path. We have a president right now, Joe Biden, who accepts science, but he’s not doing anything to get us off the path of fossil fuel use. So that’s what I’m trying to address with this book.

Robinson

The striking thing about climate politics in the United States is that you have one party that outright denies the facts of climate change. And then you have another party that at least rhetorically claims it understands the scope of the problem and says it’s very seriously committed to solutions. But then take Barack Obama. He talked about how seriously he took climate change and then boasted that the U.S. reached greater heights of oil and gas production under his tenure than under any previous administration.

Chomsky

I started my book under the Trump administration, but I finished it under the Biden administration. Under the Obama administration, emissions did flatten and start to lower for the first time since 2005, which was the height of U.S. emissions. But those changes were, on the one hand, so minuscule in comparison to what we need to be doing. And on the other hand, basically due to two things: one, the recession, and two, Obama’s promotion of natural gas and fracking. So what we see is a slight decline to a new baseline. But it’s still way, way too high. It’s a one-time shift from coal to natural gas; it’s not going to keep going down. There was too much celebration of really minimal achievements.

Joe Biden had some larger talk in his campaign—I see a comparison here with immigration, another issue I’m concerned about. There were high hopes for what a Biden administration would do. But once in office, he doesn’t really care about climate; he doesn’t really care about immigration; those are going by the wayside. And everything keeps moving further toward the right, so as not to be vulnerable to Republican attack. And that’s just really discouraging considering that the future of humans’ ability to live on Earth is at stake.

Robinson

My impression too, was that some of the impressive rhetoric or policy promises on climate coming out of Biden were, in large part, the result of the fruit of very successful diligent activism on the part of the Sunrise Movement and others. And I think the same is true on immigration. Progress has been made because politicians have been put under immense pressure by those who are committed and organized. What does come across in your book is that solutions are far more than technical. They also require organized and active human beings making things happen. The political system is going to be very resistant to making things happen.

Chomsky

Yes, absolutely. There has certainly been a lot of push from below. Every time the IPCC meets, there are counter movements protesting what’s going on. They get a lot less attention. The concept of a Green New Deal came out of the conjuncture of a lot of popular organizing and a very small number of extremely progressive voices in Congress. The Ed Markey/AOC proposal was very ambitious but not very well fleshed out. It was a first step. Bernie Sanders put forth a much more fleshed out proposal for a Green New Deal. But the Sanders proposal, and the Green New Deal for Europe proposal, which is quite similar to Bernie Sanders, haven’t gotten any traction or any attention. And those are really the proposals. They’re very concrete and very well worked out for the kinds of political socioeconomic changes that are actually going to get us not just off fossil fuels. Part of the problem is that fossil fuels are one of the greatest culprits. But there’s also a hidden narrative saying that we have to create non fossil forms of energy, and then we can continue to consume and profit as much as we want. Even the oil and gas companies are saying, Yeah, more funding for alternative energy.

Robinson

BP is “beyond petroleum” now. They’ve rebranded themselves. [[Note: BP eventually abandoned its “beyond petroleum” greenwashing project.]

Chomsky

But they’re not looking at the larger political economy of what’s going on. The fact is, there is no form of alternative energy that’s going to allow us, especially those of us in the United States—who are the biggest consumers in the world, and have been historically—to continue consuming energy at the levels that we are. It’s all very well to talk about alternative energy. We need alternatives to fossil fuels. But we also desperately need to look at how we can greatly reduce our use of energy if we want those alternative energies to actually function for us.

Robinson

One of the valuable aspects of your book is that it helps people get past hopelessness. When one looks at the predictions of what climate change is going to wreak upon humanity, you can become very despondent. Your book says, Let’s think about the actual solutions to this problem. Let us assume that we care about the future of humanity and believe that we can have a good and sustainable future. Then, what are the questions that we ask? You do puncture a lot of the easy solutions to climate change. And you do suggest that “clean” or “net zero” are buzzwords that are used that imply that we don’t have to do very much in order to solve the problem.

Chomsky

About a decade ago, a Colombian union leader really helped to shape my thinking. I’ve done a lot of work in the coal region in Colombia with communities displaced by coal mining and with unions in the coal mines. In one of the delegations that we took to Colombia, a representative from the Sierra Club, who had just been hired to run their Beyond Coal campaign, came on the delegation, and she confronted the union leader and said, You know, don’t you agree that we need to stop mining coal? And he stared at her for a long moment. And he said, We are not mining this coal for us. You’re asking the wrong person. We are mining coal for you. We export 100 percent of this coal. It’s not for us. And then he went on to say that if you think you’re going to continue to consume just as much energy by switching to what’s called “clean sources,” it’s not going to happen because there’s no such thing as clean energy.

Every form of energy relies on extraction of resources from the earth. It relies on industrial production, and it creates waste. So you have to recognize that. Instead of just saying, Yes, we’re going to switch to a different form of energy, understand that you, the United States, are the biggest consumers of energy. And you need to find a way to live within what some scholars call planetary boundaries. You need to recognize that there are planetary boundaries. And that huge over-consumers need to share the resources fairly with people like the indigenous people in this region of Colombia who have no access to electricity at all.

Robinson

This is often wielded as a gotcha point by the right. I read the pages of the Wall Street Journal regularly in order to keep tabs on what the capitalist class is doing. And one of the things that comes up in the climate op-eds is the idea that, Well, electric cars lead to all this dirty mining. “Your favored green solution actually has negative environmental effects in these other ways.” And I think there is a temptation, obviously, to cling to your favorite green solution and say, “No, that’s not true.” But the reason that they are deploying this argument is to countenance doing nothing, or to suggest that there is no alternative to massive fossil fuel use. You point out that we can accept the fact that there is no perfectly green energy and still believe that it is incredibly important to wean ourselves from fossil fuels.

Chomsky

Absolutely. And what we call alternative or clean energy, I would say it’s a relative term. We need to say cleaner energy, and we absolutely do need to shift to cleaner forms of energy, but not individual electric cars. And I was just reading the statistic that 80 percent of new vehicles sold in the United States last year were SUVs and light trucks. So we’re not even talking about cars. We are talking about trucks and SUVs. So, yes, we need new technologies for transportation. But we also need new systems of transportation that get us out of our cars. And we also need less transportation. Only 15 percent of the planet’s population has ever been on an airplane. Like everything else, we are the worst culprits in air travel. And air travel is one of the worst forms of transportation in terms of emissions. So thinking about global economic equality is a really important aspect here. We need to think about how not to consume more than our share, recognizing that there is a cost to every form of energy production. Humanity needs energy, but we should prioritize basic human needs over the luxuries of the wealthy in terms of what we are going to use our energy for. There is a cost to every form of energy.

Robinson

Ford Motor Company announced recently that it is coming out with the electric version of its signature F-150. Colossal truck. So you’re saying that electric F-150 trucks are not, in fact, the path to sustainable transit?

Chomsky

We Americans are very wedded to our cars. When we look globally, we can see that there are other industrialized countries that have very high standards of living, that consume a lot less energy, and create a lot fewer emissions than we do. And they have very different kinds of transportation systems. In places like Japan, people have all of the basic human needs, the kinds of things that we want, like low infant mortality, high levels of education, with far fewer emissions. Now, Japan still emits a lot more than its fair share of emissions. And I’m really attracted by this fair share concept. And then how can we reorganize so as not to consume more than our fair share? Those who have done these calculations, I should point out, say that we have already used more than our fair share of the carbon budget that remains if we are going to remain within the 1.5 degrees centigrade limit to global warming that the IPCC has recommended. Pretty much all scientists agree that beyond 1.5 degrees C, we’re moving into the catastrophic range. It is affecting us in the wealthy parts of the world but not as catastrophically as it is affecting people in the poorer parts of the world.

Another thing that occurred while I was writing the book was, of course, COVID, and I looked at economic slowdowns. Now, obviously, the economic slowdown under COVID happened under the worst possible circumstances. There was no planning for it. It happened from one day to the next. But there are some things that we can learn from it. This is kind of what the Green New Deal for Europe proposes. If we were to plan for an economic slowdown that prioritized the sectors that meet human needs, and if we were able to do it in a planned and managed way, so as to keep the idea of basic human needs central, we could actually live with much less energy. I would also point to the concept of a good life for all within planetary boundaries. There is a large portion of the world’s population that does not have access to a good life, to the energy and consumption that is necessary to have things like infant survival and access to clean water and access to education. But those things are not the most energy-intensive sectors. We can build out those sectors like health and education, culture, art—those sectors that can improve the quality of life—while pulling back on those sectors that consume a lot of energy such as SUVs. We can create alternatives for some of those high-energy consumptions in order to prioritize a good life over profits and high consumption.

Robinson

You talk a lot in the book about the concept of degrowth and the extent to which well-being is measured accurately by GDP. If not, what alternative measures need to be used? You cite Jason Hickel, who’s written for our magazine a couple of times about this. He’s part of the degrowth movement or the degrowth set of ideas. The idea that we need to shrink our economic activity because it’s currently unsustainable has been attacked as if it’s going to cause austerity. The idea is that you are taking poor countries and telling them that they can’t grow, that they can’t have the standards of living that everyone else has, that we ourselves are going to have a tremendously reduced standard of living. In the book you clarify that what we’re actually talking about here is building up standards of living, but also curtailing those parts, especially in countries like the United States, of our economic activities that are actually destroying the planet.

Chomsky

I like to use the term quality of life over standard of living. I feel like standard of living has been so closely associated in people’s minds with conspicuous consumption. Standard of living rises when you buy more junk that you don’t need. So I think defining the goal as quality of life helps us move away from the idea that we must keep producing and consuming more for the GDP to rise. We need to recognize that we are actually over-consumers in the United States. We are producing and consuming too much. Things that fulfill basic human needs—I’m also talking about things like higher education, art and culture, forests and beaches, and all kinds of things. Most people in the United States are struggling with debt, housing, and healthcare. Why are we struggling with these basics yet we have new iPhones every year? Our priorities are misplaced. And the reason that our priorities are misplaced is that our economic system, capitalism, is based on profit-making activities. We may be over consuming, but we’re also the victims of this rat race where we’re really consuming to fill the coffers of the very rich. We’re indebting ourselves to fill the coffers of the very rich. The resources of society need to be redistributed. The wealthier you are, the more stuff you’re going to need to give up so that people can have healthy food and decent housing and clean water and healthcare and free higher education.

Robinson

Another criticism that is often made of the Green New Deal is—I think Bill Gates has said that this—is that it’s Marxist. He said, What’s the job guarantee doing in a piece of climate legislation? But there are very good arguments for why we have to address these other things that don’t look climate related at the same time. It’s part of this effort to produce this holistic quality of life and reallocate social resources from things that are wasteful to things that are beneficial and good.

Chomsky

One of the things that degrowth economics talks about is not only a job guarantee, but a shorter workweek. Having a job is part of what a good life for all means. Why should we have to struggle to get jobs? Why should we have people who can’t get jobs? That’s part of the irrationality of how our system works. We can cut back on unnecessary production and consumption, along with eliminating unemployment, to fulfill this concept of a good life. Degrowth economics is very much based on the idea that, instead of making GDP the measure of all things, which requires that we increase production and consumption irrationally, we should make human needs the measure of all things. Everybody deserves to have a job, and everybody deserves to have leisure. If we were not tied to the profit system, and the need to keep production up in order to survive and to have a job, we could reallocate how our work time is spent, so that our work is based on what we as a society actually decide are our priorities, which are the needs of people rather than the needs of corporations to make profits.

Robinson

That shift is essential, in order to make sure that we don’t continue to engage in the ever-increasing infinite use of energy with diminishing returns in terms of how much human utility it produces for most people, right? The endless accumulation of wealth is extremely costly to the planet.

Chomsky

And it’s extremely costly to the poor.

Robinson

One of the reasons that science isn’t enough is because issues of justice and just distribution are so crucial. You have an article coming out in TomDispatch called “The U.S. is Exceptional.” And it turns out that the U.S. is exceptional in ways we might not want to be. One of the facts about climate change is that it is a huge act of theft by the Western world against the global south. Those of us who are the world’s worst emitters of carbon are inflicting damage upon the poor globally. It is kind of an upward redistribution of wealth in that it harms one set of people to enrich another set of people. Thinking about issues of justice and distribution is not science, but is inseparable from how you address this problem.

Chomsky

The concept of the atmospheric commons is also a useful one. If the atmosphere belongs equally to all of us inhabitants of planet Earth, including future generations, everybody deserves equal access to it. But we have already stolen from today’s poor and from future generations. So when we talk about the United States having a carbon debt, it’s what we have already stolen, and we’ve stolen from the people who need it most and from the future.

Robinson

Let’s discuss what people as individuals ought to think about their personal responsibility. Obviously, every single person can only do some small amount, and we don’t want to exonerate people from responsibility, but we do want to acknowledge the limits of what one person could do. You talk about this question of consumption choices. Should you be a vegetarian? Should you buy a Prius? You’re very fair-minded. But you do say, No!, to the question of buying a Prius.

Chomsky

I have so many friends who’ve bought the Prius.

Robinson

When a person feels overwhelmed by the climate crisis, by what their obligations and capacities are, how do you approach this?

Chomsky

So I do think individual behavior is important in a number of different ways. Understanding where individual behavior fits in the larger picture helps. It’s important mostly because it can help us not just think about our individual consumption but to conceptualize the problem in larger terms, and to begin to take action in larger terms. Everybody who starts to become conscious of overconsumption probably has their own personal limits. My own personal limits have changed. Before COVID, I spent a lot of time traveling by air to different conferences and events, and I always comforted myself by thinking, Well, I’m spreading the good word and educating people. And I realized, Wow, that was so stupid. I really don’t need to do that. It’s important to recognize what’s wrong with our individual patterns, and not just to change our own individual pattern, but to change the structures that put us in these positions.

It’s really hard to live in this country without a car, especially certain areas of this country, because they’re designed for cars. So what we need to do is look at transforming transportation systems. We spend a lot of time focusing on energy production—power plants and electricity. And while that is important, less than 50 percent of emissions come from the energy sector. Emissions come from the transportation sector, the agricultural sector, the industrial sector, and the building sector. So we need to look at it in a comprehensive way and change all these systems. This is another problem with alternative energy. One area that alternative energy relies on is what they call biofuels, which some activists call agrofuels, which actually spread plantation agriculture and deforestation in the third world. And then we blame the third world countries for the emissions to fuel our consumption.

Robinson

When one realizes how interconnected everything is, and how much things have to change, it’s easy to become overwhelmed. One of the things that we have to avoid, I think, is concluding that because this is a crisis of capitalism, unless we overthrow capitalism, we cannot address the crisis. What are, in the near term, the major important policy interventions that we should be pushing for and hoping for? In the next five to 10 years, what do you want to see happen in the United States in particular?

Chomsky

I agree. We’re not going to overthrow capitalism in the next five or 10 years. But I do think that the Green New Deal proposals—in particular, the Bernie Sanders proposal and the Green New Deal for Europe proposal—outline some really concrete steps that could be taken very quickly to start shifting our economies away from fossil-heavy, emissions-heavy, useless production, and prioritizing some of the basic human needs sectors. So it’s not going to happen overnight. But it could start happening very quickly if there was political will. In a way, I see COVID as bringing some optimism. If people really believe that it’s an emergency and governments really believe that it’s an emergency, they can start taking measures that can make a big difference. We need to manage an economic contraction in a way that asks the wealthy to contribute their fair share instead of burdening the poor. Capitalism isn’t all-or-nothing. There are many different capitalisms. And we’re right now in a phase of a kind of savage, neoliberal capitalism. So some of the first steps would be moving ourselves back toward a kind of social welfare capitalism, which more highly regulates and taxes the rich and industry and diverts more of our society’s resources toward social welfare kinds of institutions and policies. We’ve moved away from it, and we’re still basically moving in the wrong direction. But we could shift that in the next five or 10 years.

Robinson

People should pick up your book if they’re feeling a little directionless on climate change, especially if they understand the basic scientific facts of climate change but want to move to the next phase of the discussion—to consider these deep policy questions about justice and morality. There’s a section toward the end of your book called “reasons for optimism.” In spite of all the debunking of pseudo solutions and techno optimism, and exposing the way that rhetoric and grand gestures are used as a substitute for action and the corruption of the political system, you still maintain optimism that the climate crisis can be addressed.

Chomsky

Absolutely. I do. We don’t have to wait for scientists and engineers to develop new technologies and discover new things. We already have all the tools that we need. We just have to turn our attention to them.