The Annihilation of Florida: An Overlooked National Tragedy

An accelerating race to destroy Florida’s wilderness shows what we value and previews our collective future during the climate crisis.

You can tell many stories about Florida, but one of the most tragic and with the worst long-term consequences is this: since development in Florida began in earnest in the 20th century, state leaders and developers have chosen a cruel, unsustainable legacy involving the nonstop slaughter of wildlife and the destruction of habitat, eliminating some of the most unique flora and fauna in the world.

In his 1944 book That Vanishing Eden: A Naturalist’s Florida, Thomas Barbour bemoaned the environmental damage caused by development to the Miami area and wrote, “Florida … must cease to be purely a region to be exploited and flung aside, having been sucked dry, or a recreation area visited by people who … feel no sense of responsibility and have no desire to aid and improve the land.”

Even then, a dark vision of Florida’s future was clear.

Most of this harm has been inflicted in the service of unlimited and poorly planned growth, sparked by greed and short-term profit. This murder of the natural world has accelerated in the last decade to depths unheard of. The process has been deliberate, often systemic, and conducted from on-high to down-low, with special interests flooding the state with dark money, given to both state and local politicians in support of projects that bear no relationship to best management of natural resources. These projects typically reinforce income inequality and divert attention and money away from traditionally disadvantaged communities.1

Consider this: several football fields-worth of forest and other valuable habitat is cleared per day2 in Florida, with 26 percent of our canopy cut down in the past twenty years. According to one study, an average of 25 percent of greenhouse gas emissions come from deforestation worldwide.

The ecocide happening here is comparable for our size to the destruction of the Amazon, but much less remarked upon. Few of the perpetrators understand how they hurt the quality of life for people living in Florida and hamstring any possibility of climate crisis resiliency. Prodevelopment flacks like to pull out the estimates of the millions who will continue to flock to Florida by 2030 or 2040 to justify rampant development. Even some Florida economists ignore the effects of the climate crisis in their projects for 2049, expecting continued economic growth. but these estimates are just a grim joke, and some of those regurgitating them know that. By 2050, the world likely will be grappling with the fallout from 1.5- to 2-degree temperature rise and it’s unlikely people will be flocking to a state quickly dissolving around all of its edges.

The Corridor to a Better Future?

About the size of Greece, Florida is the jewel in the crown of the amazingly biodiverse Atlantic Coastal Plain. The state has 1,300 miles of shoreline, 600 clear-water springs, 1,700 ravines and streams, and over 8,000 lakes. More than 3,000 native trees, shrubs, and flowering plants are native to Florida, many unique to our peninsula and also endangered due to development. Our 100 species of orchid (compared to Hawai’i’s three native orchids) and 150 fern species speak to the moist and subtropical climate across many parts of the state.3 Florida has more wetlands than any other conterminous state—11 million acres—including seepage wetlands, interior marshes, and interior swamp land. Prior to the 1800s, Florida had over 20 million acres of wetlands.

As Jen Lomberk of Matanzas Riverkeeper describes it, Florida’s aquifer is unique because it is “so inextricably connected both underground and to surface waters. Florida’s limestone geology means that pollutants can readily move through groundwater and from groundwater to surface water (and vice versa).” In a sense, the very water we drink in Florida lays bare the connections between the often-invisible systems that sustain life on Earth and reveals both the strength of these systems and their vulnerability.

Land trusts and other environmental advocates across the state are doing heroic conservation work to protect the state’s unique biodiversity. Thirty thousand acres of Apalachicola River floodplain just received substantial protections, for example. But this occurs in the face of ever-stiffer opposition: “the worst I’ve ever seen,” the head of one major Florida-based conservation group told me, referring to the predatory and anti-science environmental actions of our Republican-dominated state legislature.

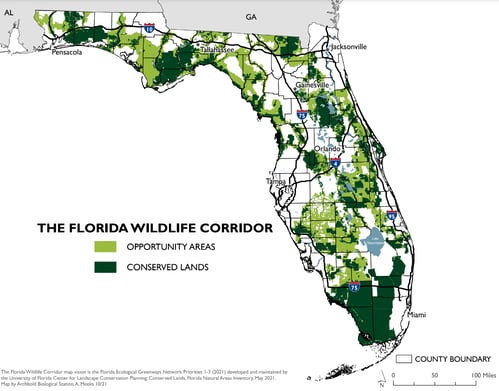

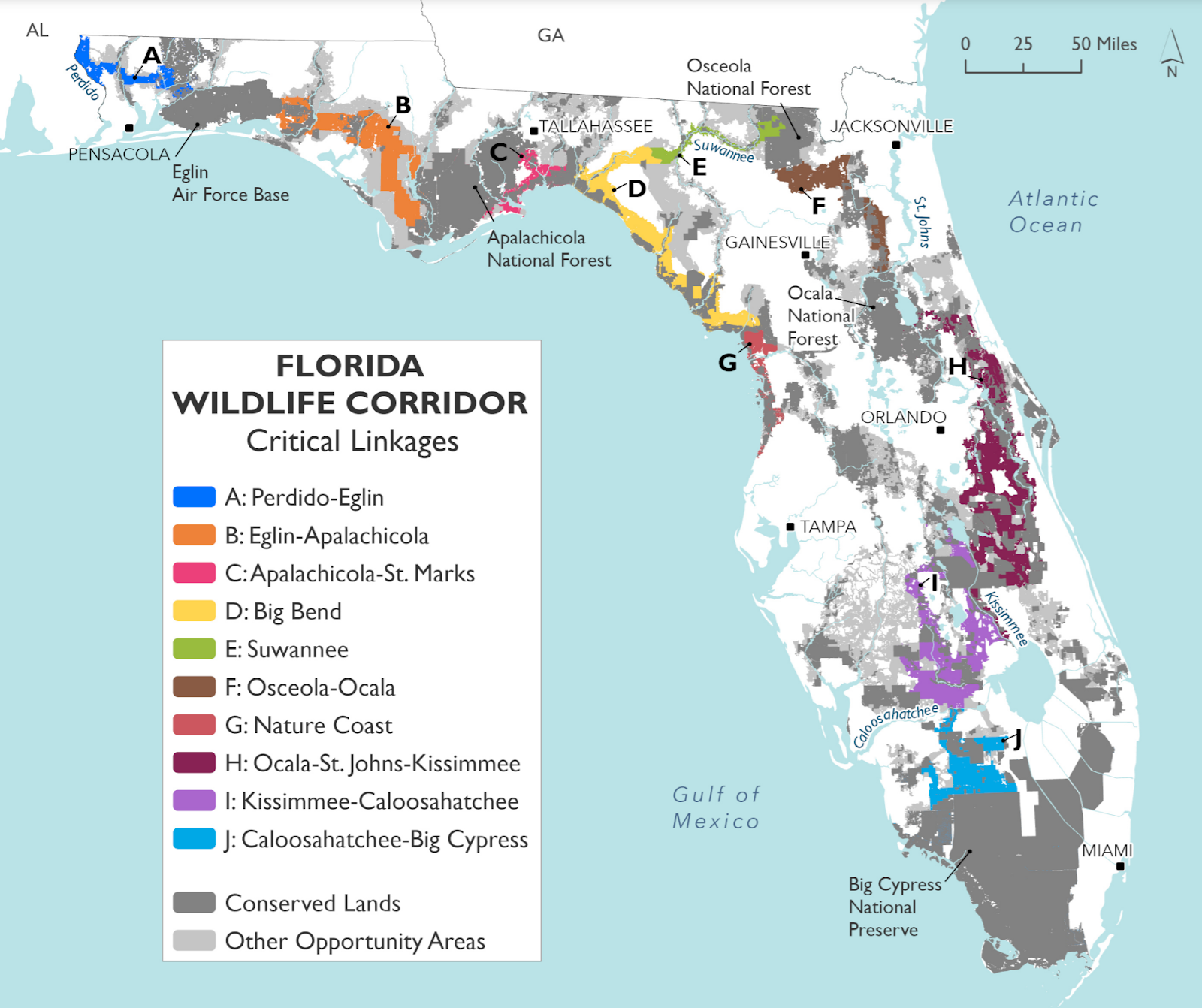

Given this deteriorating situation, the idea of a Florida Wildlife Corridor stands out from most conservation efforts because it reflects a biological truth: without sufficient connection between remaining wilderness areas within the state, even our most remote sanctuaries will become walled-off islands of biodiversity that, over time, will lose their richness. Animals like bears and panthers rove over vast areas, and habitat fragmentation makes their lives almost impossible.

The people who conceived of the corridor and manage the related foundation’s activities have remained largely apolitical so that they can court state funds. But there is something inherently and joyfully political in how the corridor’s creators imagine it as not just a physical set of connected places. The corridor is also a narrative that combines “conservation science with compelling imagery and rich storytelling to … inspire [the corridor’s] protection.” Advocacy on behalf of the Florida Wildlife Corridor includes “documentaries, books, videos, and vivid photographic presentations that introduce these natural areas to Florida residents and visitors of all ages.”

Shown on maps as a slow curve up through South Florida, Central Florida, and into the North Florida Panhandle, the wildlife corridor offers a quixotic hope for the future. The ultimate goal is 17.7 million acres, with 9.6 million acres existing conservation land (some of it compromised by other uses, like ranching and silviculture) and 8.1 million “opportunity areas” for future conservation, including through the underfunded Florida Forever land acquisition program and the Rural & Family Lands Protection Program. The creation of the corridor also gives an overriding purpose, or story, to other environmental projects that feed into the corridor goal while emphasizing the importance of the 75 state parks, 32 state forests, and 171 springs that form part of the corridor.

Acquiring land for the project means being in a race against time and developers sometimes measured in months, with life and death consequences for trillions of organisms. Will the Wildlife Corridor form the core of a reflourishing of Florida’s wild spaces that also enhances the quality of human life here? Or will it be a last stand, becoming in time a wildlife fortress or land-bound island surrounded by pollution, unnecessary infrastructure projects, and urban sprawl?

The answer lies in whether rural Florida can fight off the predations of its own state government, including what many here call “the toll roads to ruin.”

The Toll Roads to Ruin

If the idea behind the Wildlife Corridor represents a profound expression of a sustainable, biodiverse future, then the toll roads are the purest distillation of capitalist evil. Governor Ron DeSantis, the Florida legislature, and the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) seem determined to ram these roads through rural Florida—even as the people who live there, regardless of political affiliation, are united in fighting the roads and the destruction they will bring with them.

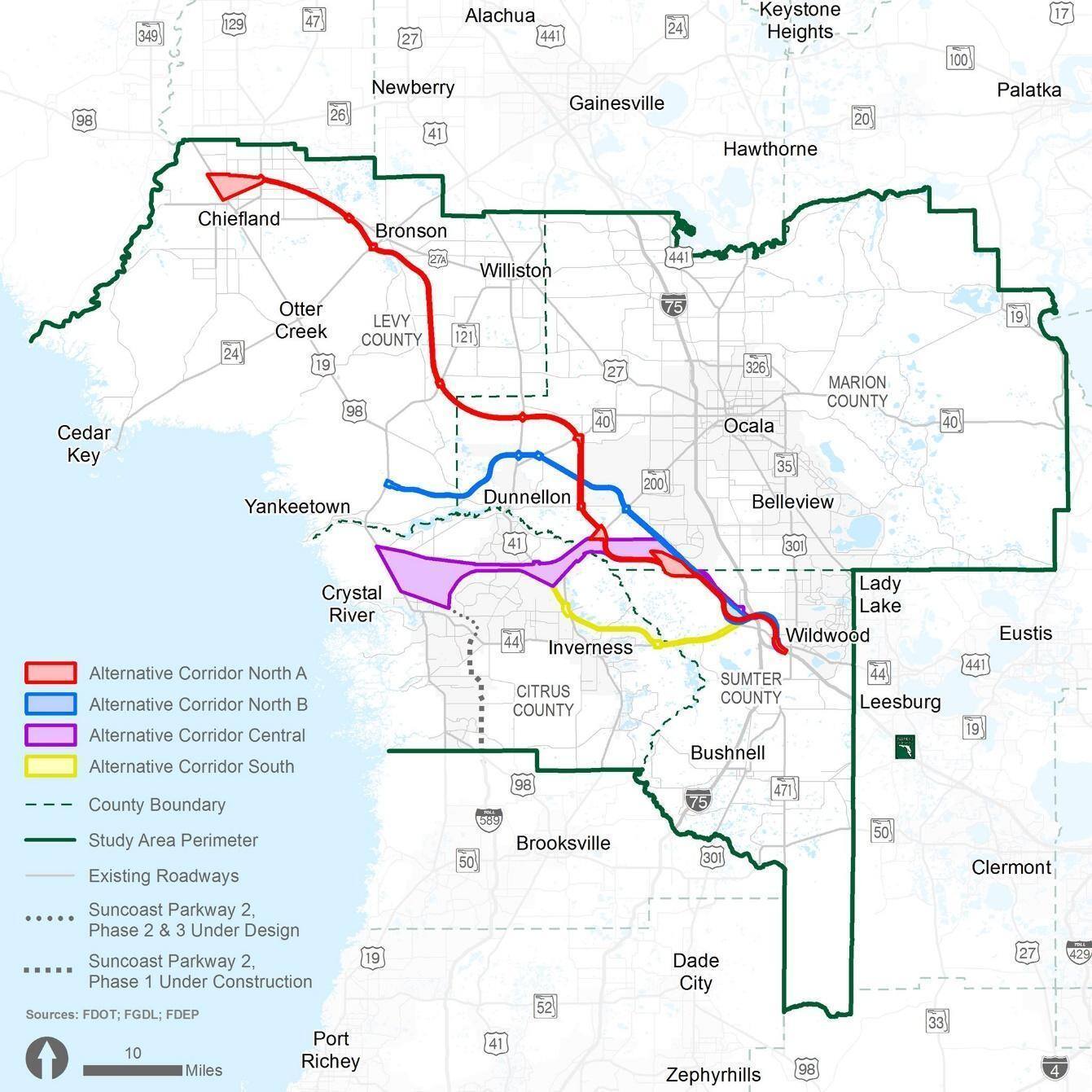

The Northern Turnpike Extension is just the latest attempt by politicians and developers to crack open some of the last truly wild and rural lands in the state, through Citrus, Levy, and Marion Counties. This roughly 79-mile highway—often referred to as “billionaire boulevard,” referring to the main beneficiary of it—would connect Wildwood, where I-75 begins, northwest to the city of Chiefland. The ostensible reason is to relieve congestion on I-75, which runs down the middle of the state, but the highway would bring the sprawl of South Florida north, even though Florida already has more miles of toll roads than any other state.

Despite prior highway boondoggles, the Northern Turnpike Extension and future toll roads may be approved and completed over land meant to form part of the Wildlife Corridor.4

With 93 percent of public comments opposed, according to a group against the roads, FDOT tried to minimize the public outcry by failing to record those comments. Even former governor Jeb Bush, coming out of pandemic slumber to pen a disgraceful pro-roads editorial for the Tampa Bay Times, couldn’t convince Floridians. Residents also saw through politicians’ inaccurate claims that the roads would be necessary to expand broadband internet to rural areas.

Most sensible urban planners will tell you that adding more highways to solve congestion just leads to more congestion. Environmental organizations and residents are quick to point out that existing roads are underused, meaning the toll roads represent a classic case of induced demand. Politicians who support them often have received substantial campaign contributions from the entities that stand to profit.

The FDOT’s own map for this new toll road project could be considered deceptive or, at best, incomplete. “Opportunity zones” for economic development near a river that regularly floods its banks by 8 to 10 feet have become an object of scorn among the locals—and exemplify the engineering problems that would, in the aftermath of a road being built, plague residents for years to come.

“I have no idea what big employers … near that river” would benefit,” Robert Roscow, an architect who owns property in the area, told me. “Maybe places to buy beer.”

Transparency does not seem to be FDOT’s strong suit when dealing with the public. FDOT appears to have deemphasized an analysis of the feasibility of widening I-75 so that the Northern Turnpike Connector seems like the only option.

Roscow, who has prior experience with FDOT, said the response to his query about which businesses would benefit from the toll road revealed incompetence at best: a dairy actually in a different county and no mention of large local education and medical businesses, who don’t need the tolls roads to conduct business.

FDOT, according to Roscow, did not provide detailed aerial maps of the routes at public meetings, despite having a website devoted to detailed aerial maps of the state.

“The first presentation on the toll roads to the city of Inverness … the city council kind of knew where [FDOT] was talking about, but not exactly,” Roscow said, because the maps were crude. Seen with the precision maps from FDOT’s own website that Roscow had to create himself, one route clearly goes through a lake and another right through the town of Hernando.

The anguish of people with a connection to the land, who understand the importance of place and of intact ecosystems, is palpable.

“They can have the house,” one resident commented on an anti-toll-road Facebook thread with hundreds of similar comments. She had posted a photo of a huge oak tree in her yard. “But damn it if it makes me cry thinking this tree will be bulldozed.”

Marjorie Shropshire, a lifelong Florida resident active in environmental causes and organizations, sees part of the problem as lawmakers who “do not understand how they fit into nature or how nature works. Perhaps they just don’t care. Many hold the belief that there is no ‘value’ to nature. … If it isn’t ‘improved,’ it’s worthless. There is a lack of recognition of the ecosystem services that conserved lands can provide, therefore it is easy to claim that more conservation lands are not needed, or that they are too expensive.”

The FDOT’s own studies of the proposed toll roads demonstrate substantial effects on wetlands and long-term pollution and degradation of water quality. Two of four potential routes found to be “moderate” in these impacts are only moderate in comparison to the remaining routes. The state’s Southwest Water Management District does not support the toll roads.

Even the Ocala Horse Alliance came out against the project: “The toll road will destroy hundreds of small farms and trail areas [and] will be accompanied by irreversible negative environmental damage [including] massive urban sprawl, will decimate pastures and open spaces and promote excessive commercialization.”

Currently, FDOT has fast-tracked picking a route by year’s end even as horrific images of the destruction wrought in Pasco County, just farther south, hit conservation Facebook groups from the already-approved Suncoast connector toll road. According to local residents, developers even bulldozed over critical migratory bird nesting areas, resulting in Sandhill Cranes dying on the nearby highways as they tried to protect their (flightless) young.

Having driven through Pasco and adjacent counties down to Tampa in early 2020, before the pandemic hit, I can attest to the horror of the destruction caused by the new road construction and adjacent road-widening. Heavy bulldozers were everywhere, leveling everything. The sense of bearing witness to the first, vigorous days of the creation of Mordor hung heavy in the air.

You may think this is an exaggeration, but the feeling of dread only grew as I came upon a whole family of seven raccoons slaughtered along the roadside. The mother had clearly gone back for her babies, only to perish with them. Later on, I saw a gopher tortoise eking out an existence on the trough of grass between Route 19 and the decimated area that used to be its home.

On the stretch near Homosassa Springs, a rare Florida mouse, terrified, dodged for its life through four lanes of heavy traffic—just to get to a tiny clump of sod next to a newly erected crosswalk sign. Its palmetto habitat had just been razed by developers.

How Roads Bring Ruin

Just ramming such roads through farms, forest, and swamp destroys many hundreds of acres. But, worldwide, roads are often just a pretext for developers and others to come in and transform an area forever. This is why, for example, environmentalists and indigenous groups in Bolivia recently opposed a road through sensitive territory that would forever change the region.

The process works roughly like this: the initial road construction creates potential flooding, erosion, and water quality issues. In addition, road builders don’t always follow proper environmental guidelines, resulting in pollution to the surrounding areas. If runoff containment is insufficient, heavy metals and other contaminants enter the soil.

This initial phase kills and displaces wildlife, liquidates the important mature pines and live oaks,5destroys rare plants and trees, and allows extremely harmful invasive plant species a foothold. No care is taken to check for invasive plant seeds or to decontaminate heavy equipment. Rare native plants largely have no protections and frequently Florida native plant groups on Facebook stage interventions for habitat about to be destroyed for development, by trying to transplant rarities to other areas.

For large animals like bears, the roads will be deadly and drive them further into more distant, smaller territories. The fencing of verges and median strips made of concrete barriers accelerates ecosystem fragmentation via isolation of populations. Fifty percent of all annual Florida panther deaths occur on roads. All 11 panthers that have died in 2022 so far were hit by vehicles. (Nationally, roadkill deaths add up to more than one million vertebrate animals per day.)

Street lights immediately create additional light pollution in formerly dark-sky rural areas. The now-favored white LEDs, while more energy friendly, are actually worse for nocturnal wildlife and insects because their glow disrupts life cycles, decreases reproduction, and thus further degrades ecosystems. According to a 2016 study, every year, the world loses another two percent of the Earth’s dark skies to light pollution.

Next come the gas station mega complexes, with dozens of pumps built on a half-acre of concrete, alongside full-service convenience stores, which replaces forest and increases light pollution, as well as groundwater pollution. In the opinion of experts, building new stations can easily lead to contamination of groundwater and the aquifer due to gasoline tank leakage.

This stage may be accompanied by the creation of dozens of single-family homes on large lots of one to five acres. While these homes may have a lower ecological footprint than some forms of high-density housing,6they bring more clearcutting and, usually, homeowners whose relationship to the surrounding wildlife can be antagonistic, causing further disruption of ecosystems.

On the heels of these changes, the larger-scale developments appear, often extending from the existing urban areas, but sometimes plunked down in the middle of nowhere, with the expectation of further infrastructure and services accreting around them. Creating these subdivisions and planned communities is the main goal for developers. This kind of development involves wholesale clearcutting similar to what’s done by ranchers in the Amazon for agriculture, up to 5,000 acres at a time wiped clean, including the topsoil: the complete slaughter and dismantling of a complex system. In its place will come thousands of overpriced, often poorly made houses, with ironic names like “Canopy Homes.”

Ironically, mining operations that follow the law have to protect the environment to a far greater extent than development projects.

Where regulation is strong, topsoil is treated like gold, Jeremy Gilmer, a mining consultant, told me. The topsoil is separated and stored in piles and nurtured with “water, mixing, and care” so that organisms can continue to thrive. The process is costly and timely, but essential if land is to be restored after completion of a mining project. But, Gilmer noted, on most civic construction and development sites, “contractors strip ground and the materials are mixed, piled and often left to rot and eventually wasted in use as regular fill or left in a pile. No effort is made to retain the valuable, important and ‘live’ topsoil.”

Any wildlife that manages to flee often perishes in new, unfamiliar environments. In place of the native organisms come lawns of useless sod propped up with chemical fertilizer and herbicide. As is already the case in places like Rainbow Springs State Park—adjacent to a proposed toll road route—developments will creep right up to the doorstep of protected areas. Without a buffer, runoff and other pollution will contaminate what are meant to be sanctuaries for nonhuman life. The close proximity of homes to forest also makes it harder (sometimes impossible) to perform the controlled burns that have, to date, made Florida wildfires less prevalent than in places like California.

Echoes of these same dysfunctional processes even infiltrate supposed “green” energy in the form of Southeastern forests destroyed to send fuel to biomass plants and efforts by utility companies to nix personal solar in favor of industrial solar farms that, not properly regulated, destroy habitat in a way similar to the worst kinds of development.

The damning thing is how invisible this ecocide feels to those of us who live here and care. The nature of clearcutting with soil removal leaves no evidence of the crime behind—just a void. The way in which much of the ultimate green-lighting for ecocide occurs at the local government level also makes much of it invisible, doomed to reside at best in regional news cycles, but often not even reported on there.

Manatees and panthers are iconic Florida species that people often rally around, but such sporadic enthusiasm is not enough if nothing happens when so many of them are killed. Palmettos are critical to other species’ survival and can be over 5,000 years old, but they form thickets low to the ground, are considered a nuisance to developers, and the first things to be bulldozed.

Gopher tortoises often suffer a horrific fate. If you have bought a house of a certain age, in the dry sand scrub that was once prime tortoise territory, chances are you live on top of the dead bodies of gopher tortoises—slaughtered outright or sealed alive in their burrows to suffocate or starve to death. Reports estimate more than 100,000 gopher tortoises have died this way. The true number may be twice that.

Just as with the palmettos, a keystone species, gopher tortoises support all sorts of other organisms, which use their burrows. What this means is that development wipes out entire ecosystems and kills a host of other animals when either of these species is extirpated. This then affects in a profound way the economic services these ecosystems had provided to human beings.

These days, there is a relocation program for gopher tortoises, but it is of dubious quality, with fudged mortality rates, and further weakened by a typically pro-business Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission. Treating the most docile, harmless, and important of Florida species with such cruelty should be a crime.

Mitigation programs in general only preserve some remnant of a highly complex ecosystem, in the form of the animals saved—the connectivity and all of the richness built up over thousands of years is lost forever. Worse, legacy licenses to outright kill gopher tortoises have no end date, meaning some companies still can legally chop up live tortoises to build their subdivisions.

In other kinds of habitat, many of these developments will be built by filling in wetlands. The most rudimentary provisions will be made for flooding and erosion control. Even land set aside as environmental easements to mitigate development may eventually be on the chopping block. Inadequate stormwater ponds, with lower water quality standards, that do little to filter out pollution will be put in as mocking mirrors of the karst features and natural water bodies bulldozed over. Often, migratory waterfowl return to these bodies of water and use them even though the food value is now low and the toxins in the water higher. A valuable resource has been rendered a parody of its former self.

DeSantis has created an Office of Resilience and Coastal Protection to address climate crisis—but, if Republican imagination of the past is any indication, money for these protection projects will be diverted to unrelated pet projects or even given to the very developers who have contributed to the problem, much as oil companies now try to greenwash their image.

More importantly, what use is a resiliency agency that doesn’t address the threat posed by run-away development in the interior of the state? It is widely accepted now that cutting down mangroves is foolhardy, however many decades it took for that lesson to be learned. But what we’re doing in other parts of Florida is exactly the same as cutting down mangroves. Combatting increasing heat, flooding, and erosion can be matters of life and death. When you remove mature live oak trees and pine trees that help mitigate these issues, you are creating a future disaster that was partially avoidable, even factoring in the climate crisis.

How We Got Here

Florida faces so many human-created ecological emergencies that an exhaustive list would fill a phone book: manatee die-off, Florida panther habitat fragmentation, phosphate mining runoff polluting bays, forever chemicals in our water, red tide and algae blooms accelerated by pollution, and more. The story of how we got here includes concerted, planned actions by elites—including developers and parasitic politicians—but gross incompetence and stupidity as well.

You can point to the handing over of federal wetlands permitting in Florida to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP), ceded by the feds during the Trump era, in conjunction with the state legislature passing weakened urban canopy protections and other laws aimed at curbing the ability of local government to stop bad ideas and worse development. Environmental mitigation programs have reached an all-time low as well, with environmentalists having to fight off a proposed bill to allow destruction of sea grasses in return for planting them elsewhere, even as manatees continue to starve to death in the hundreds due to lack of food like sea grass.

The latest atrocity to be inflicted upon Florida is a “preemption” bill, likely to be signed into law by DeSantis, that would allow businesses to sue city and county governments if a local ordinance costs a business more than 15 percent of its profits. Republicans clearly mean for this law to give developers and other anti-environment entities—who already have an obscene arsenal of weapons at their disposal—yet another advantage.

Recently, too, the penalty for speaking out has become frightening: you can be sued by a company if you urge a county commission to reject a mining project and incur a fine of millions for impugning a company’s reputation. And when the people of Florida fund land preservation programs through passing Amendment 1 in 2014, for example, lawmakers divert the money to such noted environmental causes as millions on “an insurance fund to protect state environmental and agricultural [agencies] from federal civil rights act violations.”

What allowed much of this to happen was the elimination of the state’s growth management department, the Florida Department of Community Affairs, in 2011, a move pushed by developers. Republican Governor Rick Scott essentially abolished the department in favor of a Department of Economic Opportunity that has over the years been partially run by and advised by the very companies that have a stake in destroying places in the cheapest possible ways.

Now we have “opportunity zones” around the toll roads that are excuses to carve up rural Florida for business interests and entities like the North Florida Economic Development Partnership, which even works “nature” into their slogan—“Business Growth is in Our Nature”—and cloaks the signs and symbols of destruction and pollution in symbolic leaves and green colors. Nothing says sustainability like framing a photograph of a fossil fuel-emitting logging truck with a swath of green.

Under former governor Rick Scott and now DeSantis—who pays lip service to the wildlife corridor while undermining it with most of his policies—the stacking of regional water quality boards and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission with political appointees emboldened to make terrible decisions has become almost laughable. Last year, for example, Florida’s top wildlife official wanted to fill in a South Florida lagoon full of manatees to make a profit in real estate.

In addition to all of this, which feels like enough, the FDEP has been weakened both in how it handles violations of already watered-down regulations, and in the permits it hands out. Recently, in both North Florida and South Florida, environmentalists had to fend off exploratory oil wells from out-of-state companies—in extremely vital and biodiverse areas, with huge impacts for drinking water and general quality of life.

New legislation also takes aim at independent environmental analysis that is by nature nonpartisan: one bill passed by the Florida legislature restricts who can serve as a district soil and water supervisor. Those appointed help property owners in their area maintain the integrity of natural resources. According to one of the Leon County’s appointees, Shelby Green, the change would “restrict who is allowed to sit in these seats and decide the future of our natural, but also political, environment. If the bill passes as written, it will severely limit oversight, accountability, and citizen input [affecting] who can be a public servant.”

Worse, special interests appear to have gotten traction at the national level, with internal documents showing that the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service wants to downlist the endangered status of both the panther and the Key deer—which would again mean fewer obstacles to unsustainable development. There are only 120 to 130 Florida panthers and 800 Key deer remaining.

As one rural resident on the toll roads Facebook group put it, describing Florida’s current crop of lawmakers, “We are nothing to them, yet we elected them to hold their office. Our beautiful lands and wildlife mean nothing to them. Yet the plans they make to better themselves in their political world are what mean everything to them.”

Groups like the Florida Waterkeepers feel this increased drumbeat of destruction as well. In their 2020 report, they wrote, in an unusually blunt way, that their ecological and clean water mission was “deeply challenged … when our water resources were threatened and compromised by harmful rule changes and rollbacks, intended to fast-track development and support industry interests. New lackluster laws emerged from the state legislature that claimed to be the solution for Florida’s water woes but functionally fell short.”

The growing totalitarian nature of Governor Ron DeSantis’ reign appears to be making a bad situation worse in this regard. Florida Democratic gubernatorial candidate Nikki Fried created controversy by comparing DeSantis’ consolidation of power with the rise of Hitler, but it is not too extreme to recognize that DeSantis’ approach in Florida, including the enemies list, begins to at least feel like something approaching oligarchy, not representative democracy. A corresponding lack of government transparency, despite our Sunshine Law, protects developers and pro-development politicians while making it harder to report on environmental issues.

“Just recently a governmental body invoiced FLCGA nearly $500 for basic public information that should have been easily retrievable,” says Bob Norman, Florida Center for Government Accountability’s journalism director. “We’ve seen this kind of abusive practice on a sporadic basis for decades, but now it’s become pretty much an expected part of the newsgathering process. Far too many state and local agencies have made sport of making so-called government-in-the-sunshine as onerous and expensive and time-consuming as possible.”

An oligarchy, with its system of favoritism toward certain elites and special interests, deliberately fosters corruption as a function of its existence. It is often stacked against environmental causes in ways different from a decaying representative democracy. Combine the worst attributes of capitalism with oligarchy and in the future, Florida’s leaders may actually give developers and other special interests even more tools of suppression.

INTERMEZZO: Warning Signs of the Systemic Collapse of Environmental Safeguards

All over the world, a war on the biosphere, and thus human quality of life, is on the uptick. General warning signs of intense ecocide imminent, if not already underway, vary, but may include the following actions by government:

- Abolish oversight agencies or render them toothless

- Stack any adjacent relevant agencies with ideologues loyal to ideas of unlimited, unregulated growth

- Stack relevant water quality and wildlife management boards with cronies

- Weaken existing state environmental law and make it difficult for local government to enact stricter provisions

- Find ways to move national control of land conservation to the state level

- Use the law to intimidate activists who are fighting bad projects

- Restrict access to public records about environmental issues by being unresponsive, providing incomplete information, or charging expensive fees

- Use budding autocratic tendencies to reward special interests inimical to best practices regarding natural resources

- Enforce environmental rules or laws that remain in a tepid way, or not enforce them at all

- Create propaganda to support the idea that reckless development and new weakened environmental rules are actually progress and those who oppose it are extremists

No Place is Safe

For decades, I didn’t believe this kind of destruction could come to Tallahassee in such a rapacious way. Toll roads will not go through Tallahassee and for much of the time I’ve lived here, since 1992, most people have chosen to coexist alongside trees and wildlife. Live oaks were celebrated as something to cherish and preserve and take care of, for future generations; nature was part of the allure of the city.

The hazards of development in North Florida include our many hills, with steep ravines and constant flooding and erosion issues. Ecosystems include high pine grasslands, flatwoods, scrub, hardwood hammocks, and upland glades and caves, in addition to an abundance of lakes and wetlands. Our local laws allowed for a robust urban canopy and other safeguards that protected canopy roads and our water quality—taking into account our unique biosphere, migrating birds, and general quality of life.

The urban-rural divide in our comprehensive plan codified the value of the natural world, specifically stating that the Rural category is intended “to preserve natural systems and ecosystem functions, and to protect the scenic vistas and pastoral development patterns that typify Leon County’s rural areas.”

However, despite so much that is good in our community, Tallahassee has become a cautionary tale of how even Florida cities that have managed to retain biodiversity and climate crisis resiliency can begin to squander it quickly. Elites and special interests similar to those that push the toll roads now enthusiastically push destructive development here. DeSantis’ oligarchy is expressed in the city’s government: a city manager less and less accountable to the public; a smug mayor who silences dissent; and the good ol’ boy nature of the local Chamber of Commerce leadership, which sees itself as a thought-leader while having done little or nothing to fight poverty in traditionally underserved Tallahassee communities —which are often the ones to suffer from lack of a healthy urban canopy.

The majority of local government officials and a maze of interconnected special interests appear to have decided that we are no longer to live alongside nature. Instead, the particular wildness of nature in North Florida is something to wage war against. The mindset of an alien occupation is apparent in so many ways, especially through Blueprint, the run-away intergovernmental agency that spends our tax dollars on large-scale projects and infrastructure. Every plan that includes parks or landscaping tends to emerge from a sanitized view of the outdoors from the 1950s. (For example, a Market District park plan that was to emphasize shade trees and wilderness now features a giant tree-less lawn instead.)

Nor do we have a taxpayer-funded program for the city or county to acquire land for conservation and the public good—unlike places like Alachua County, which shares similarities to Leon County in terms of natural resources. Worse, much like governor Rick Scott’s dismantling of developer oversight in 2011, one of our economic growth agencies made changes in 2017 so that large-scale industrial projects like a recent Amazon warehouse could be approved with little public interference.

The pace of development in Tallahassee has accelerated so much the past few years that even our local property appraiser wrote an alarmed editorial. One of the biggest clearcutting developers, the Ghazvini family, now operates with impunity, despite having earned the rare distinction of receiving one of the largest fines ever doled out by one of Florida’s Water Management Districts, among other violations, for flooding an adjacent neighborhood to the point where people couldn’t leave their homes for days.

The Ghazvinis have been major backers of Grow Tallahassee, a non-profit political organization and developer PAC founded by Justin Ghazvini to exert additional influence on local elections.7 During COVID, these same developers worked with local government to deliver Welaunee, the largest annexation for non-affordable housing of environmentally sensitive land in Tallahassee’s history, holding a “public hearing” via Zoom, while not allowing a single member of the public to be heard. Adding even more harm, taxpayers will foot the bill for the new infrastructure, not the developers.

The paper of record, the Tallahassee Democrat, has unfortunately become part of the problem. The Democrat, under the current Executive Editor William Hatfield, lacks a dedicated environmental reporter and rarely makes the link between quality of life and the quality of our environment. Stories about developers and new development are more or less press releases from the developers themselves, letting us know vital information such as the fact that one developer, Hadi Boulos, “cries” when he clearcuts properties, mourning the trees. The paper ran no story when the same developer tried to hike the price of new houses by thousands of dollars after homeowners had already signed contracts.

The very Tallahassee-Leon County economic development agency the newspaper reports on spends thousands of dollars on advertisements in that publication. When confronted about sponsored articles by developers, the paper’s news director, Jim Rosica, had the audacity to write, in a Facebook comment, that these puff pieces “help support the vital journalism we provide every day.”

The pro-developer propaganda manifests in other ways, too. Mayor John E. Dailey—whose allies astroturfed public comment on environmentally suspect road construction—touts as his accomplishment our lush (supposedly 55 percent) urban canopy. Yet, Dailey has voted for all of the development that has significantly lowered that canopy percentage. Even a quick Google map search will quickly reveal clearcutting scars that make a mockery of his claim. It’s little wonder, then, that a new pro-development political news site, 4TLH, shares an address with Dailey’s reelection campaign headquarters.

Meanwhile, the messaging of the chief forester position about our urban canopy (as expressed in emails to me) has devolved from a focus on mature trees to planting saplings, even though these saplings cannot possibly substitute for the mature trees humans and wildlife both need. Our tourist brochure touts Tallahassee’s importance to migratory birds—boasting that “Here you can spot 372 of the 497 species of birds residing in or visiting Florida”—yet we have almost certainly doomed some migratory birds to localized die-offs because when they reach our area there isn’t enough food (seeds, berries, insects) because of habitat destruction.

Our land management ordinance has been watered down. Our tree ordinance has been watered down. Our burn ordinance has been watered down. Our fertilizer ordinance has been watered down. This year, the city and county may annex another 760 acres of rural, undeveloped land for more clearcut sprawl.

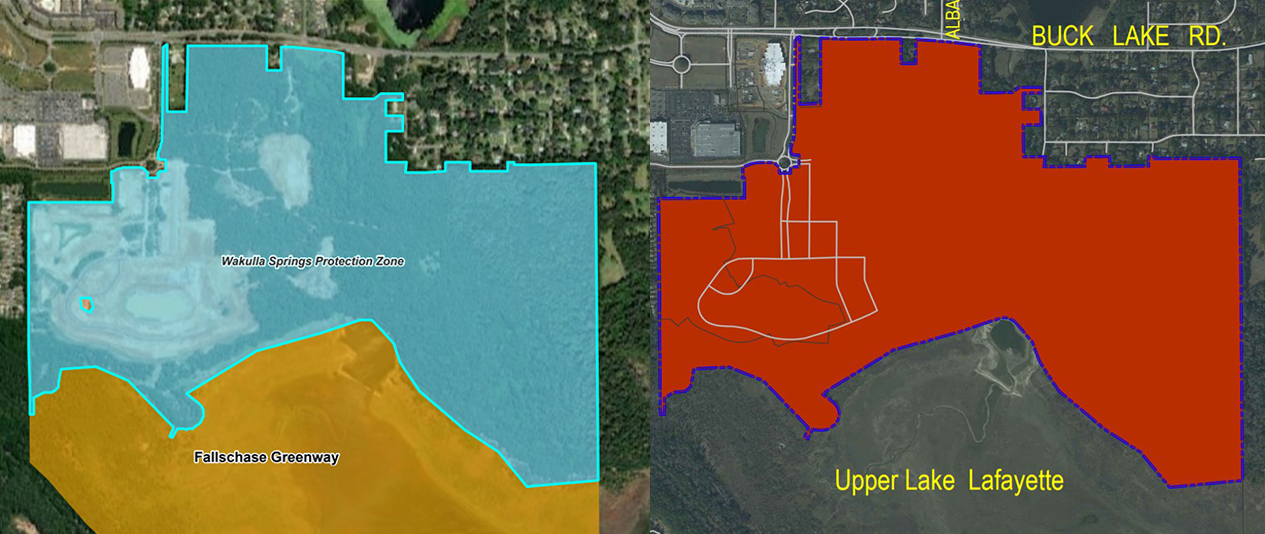

Recently, a premonition of the future for Welaunee was visited upon what’s known as the Fallschase development, above Tallahassee’s Upper Lake Lafayette. Following a sad history of potential conservation, a preliminary 80 acres was clearcut and the topsoil removed, on a slope leading down into the lake and eventually feeding into the sensitive aquifer in another county altogether. Later phases of the development will clear cut roughly another 200 acres.

As our local WFSU station reported, the developer, RMDC, did not have to include 10-percent affordable housing for “households that earn below the area median income” because of the timing of approval versus annexation by the city. RMDC will use the Ghazvini family’s Premier Fine Homes as builders.

On the page, the development of Fallschase looks sensible, the planning document prepared by Moore Bass Consulting delineating easements, cost per unit, number of units, with diagrams. There is no mention at all, of course, of what would soon be razed to the ground, as if an army had fought a battle there and its general decided to make that land of no use to the enemy. Yet the people involved in these decisions almost certainly do not see their actions as part of the problem—rather, this is the solution.

According to John Outland, a retired FDEP environmental administrator, contacted via email, developing Fallschase is “a travesty” as the site “was found to be environmentally worthy and added to the State’s Florida Forever Land Acquisition List. The loss of the forest canopy and understory vegetation on the heavily sloped land draining to the sinkholes of Upper Lake Lafayette will further threaten the quality of our drinking water supply and [nearby] Wakulla Springs.” Outland further noted that the clearcutting has continued into 2022 without any homes being built.

On the map showing desired Florida Forever conservation areas, the area being developed was marked as a “Wakulla Springs Protection Zone.” That protection, for both Leon County and Wakulla County, is gone for good and the Florida Forever program has removed Fallschase from their list of properties to acquire for conservation. The forest and water features protect nearby Piney Z Lake and Lower Lafayette Lake from pollution and runoff.

Systematic destruction and death came to the Fallschase property in April of 2021. The box turtles hibernating in their burrows would likely have been smothered or killed outright, along with the skinks and ring-necked snakes in the leaf debris. The frogs and the toads would also have had little chance to escape, nor would the flying squirrels, hibernating bats, or anything other than foxes, deer, coyotes, or bobcats. Migrating bird species known to frequent the site, some already nesting, would have had to leave rapidly, including the Hermit Thrush, Blue-headed Vireo, Yellow-billed Cuckoo, and Swallow-tailed Kite.The salamanders would not have had this luxury. Native plants and trees did not have that luxury.

We will never know any of these beings; we hardly knew of them before. Their deaths occurred off-camera, out of sight and mind, and few in the human world care that they are gone. But all of these lives existed and had meaning. Box turtles, some as old as 50 years, would have had their own nuanced understanding of the world they moved through.

Did we have a right to kill them? Do we always have a right to kill them?

Where is the Future?

The Florida Wildlife Corridor will fail—if not because of toll roads then because of the back door built for developers that allows them to treat corridor-acquired lands as mitigation for destruction elsewhere. But some failures are still successes. The Florida Wildlife Corridor can still deliver into protection many hundreds of thousands of acres of land.

The toll roads may be built, but the resistance may delay each new section long enough that conservation groups can acquire enough land in North Florida to curtail the damage, to cauterize the wound and bandage it. There is also hope in efforts like the OUTSIDE conference, which preaches a kinder, gentler kind of terraforming of Florida.

We have an urgent need for affordable housing that no amount of urban sprawl can provide and every day in my house on the edge of a ravine, I see the wasted opportunity. Instead of half-acre lots with houses built along the top of this ravine, we could have had the vision and imagination for high-density, affordable housing, while still leaving the trough of woodlands below intact. This is perhaps the most terrible truth about all of this maximized destruction: It wasn’t necessary. It wasn’t necessary, given even moderately good and sane urban planning.

Hard choices about the environment and about housing are not really hard—the hard part is that it’s impossible to get most politicians in Florida to roll up their sleeves and do the work necessary to make the right decisions. And how much more impossible is that task when it seems like decision makers loathe the place in which they live and care about power but not the fate of whole communities? Or, worse, believe the destruction they cause is the hard—or correct—choice?

In this context, and many others, the sloppy “wacky Florida Man” narrative invested in by so many journalists and pundits stings because it makes a joke out of what is deadly serious and becoming more so: A state that had been among the wildest outside of Alaska or Montana asks its citizens to passively watch as the nonhuman world is liquidated while we go on about our daily lives and others look on and say we deserve it as a “red” state.

Worse, foundational ideas buried in a settler colonialism mindset, which previously brought us the slaughter of indigenous people amid “Manifest Destiny,” are still hardwired into our society and these ideas help support the destruction. Trump wanted to “drain the swamp,” Disney literally did, and Elon Musk now wants to do it again to build more of his Space X near Cape Canaveral, in a biodiversity and carbon sink hotspot.8

One narrative that perfectly describes the situation in Florida right now is that of a death cult. Florida’s leaders are engaged in acts many societies and cultures would deem evil. They have been given the green light to exploit the state in an extractive way similar to events unfolding in Brazil, Indonesia, and other places we think of undergoing deforestation while not always realizing our complicity and our own perilous condition.

Our current way of life, centered on growth and development and material consumption, continues to use the world’s resources at a rapacious, unsustainable rate. Last year, the so-called “Earth Overshoot Day” that charts sustainable resource use fell on July 29, rather than in December. This means that once again, our use of resources outstripped the Earth’s ability to regenerate them, by a wide margin.

Our leaders perversely require of us a “pragmatism” in our observations of human predation of the nonhuman world. The moral and ethical considerations of entire species being exterminated for the cause of untenable, unplanned, unaffordable development, or even just another Wal-Mart or a parking lot, are absent from most public narrative. The modern version of capitalism-on-steroids has made the burden of explaining the intrinsic worth of anything very difficult. No gust of wind through mature pine trees, no quiet moment with bird song, could ever mean a thing.

When I was born, in 1968, the world had 50 percent more terrestrial wildlife than now. I was born into a world still alive and I will die in a world near death, brought to that condition by our own hand.

Someday, the animals may have no place to go, and neither will we. Because one thing I know is that big developers and the special interests that back them don’t stop—it’s never enough, it’s never enough, it’s never enough.

Currently, in Florida, where we still have so much to preserve, so much to fight for, we live simultaneously with a vision of the future that may be purgatory, heaven, or hell.

Which will we choose, ultimately, and what will be chosen for us?

Thanks to journalist CD Davidson-Hiers for advice and help while writing this article and to Craig Pittman for environmental reporting that allowed the most accurate sourcing of some information in this article. Further thanks to designer Jeremy Zerfoss for side-by-side map comparisons.

Correction 5/23/2022: A previous version of this article stated that William Hatfield was the publisher of the Tallahassee Democrat. However, he is the Executive Editor. The article has been updated accordingly.

Jeff VanderMeer’s nonfiction has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, New York Times, Washington Post, and the Atlantic. His critically acclaimed bestselling novels include Annihilation, Borne, and, most recently, Hummingbird Salamander.

In Tallahassee, for example, valuable infrastructure like a multi-modal pathway, is proposed for wealthy neighborhoods, while poor neighborhoods don’t even have sidewalks. The annexation of county land for a huge development with infrastructure paid for by taxpayers makes basic services harder to fund, especially improvements in the poorer parts of Tallahassee. ↩

For 2020 and 2021, Global Forest Watch estimates a total of roughly 80,000 acres of deforestation, or 40,000 acres per year. A football field covers 1.3 acres. Therefore, even being extremely conservative, Florida loses several football fields-worth of forest each day. ↩

All data according to Priceless Florida: Natural Ecosystems and Native Species. ↩

This is purely due to pressure from special interests, as these toll roads are, as pointed out by the Florida Wildlife Federation, useless and devastating projects that will cost billions. The last time the governor and state legislature tried to shove them through, in 2019-2020, their own project task forces preferred an option of “no build.” ↩

A live oak can support the life cycles of about 500 species, including various insects, and pines about 200. By contrast, an invasive camphor tree will provide berries for birds but only supports the lifecycle of one species. So a live oak or a pine tree is like a mini-ark in a sense. ↩

As separate from their environmental footprint in good land use plans compared to sustainable high-density. ↩

Public records, for example, show that almost all publicly disclosed Grow Tallahassee PAC money was contributed by a central Ghazvini family member using an address associated with the Ghazvini family. ↩

About his Space X base near a similarly sensitive wildlife refuge on the coast of Texas, Musk said, “We’ve got a lot of land with nobody around, and so if it blows up, it’s cool.” ↩