Why American Culture is So Disturbing

Societies can carry out Nazi-level atrocities without most people noticing the moral depravity around them. We need to be more disturbed by things commonly assumed to be normal.

When I talked recently to Noam Chomsky for the Current Affairs podcast, I didn’t expect him to begin an answer by saying: “Let me recount one of the most horrible experiences of my life…” The subject of the conversation was nuclear weapons, and I had mentioned the strange indifference Americans often show to the suffering of non-Americans. The “horrible experience” Chomsky proceeded to recount was something that might seem quite ordinary: a time he and his wife went to see a movie in Boston in the early 1950s. The film was about the Hiroshima bombing, and what made the experience so disturbing for Chomsky, to the point where he recounts it with a shudder even today at 93 years old, is that he realized when he got to the cinema that the film was being presented as an exploitation film, playing in a theater that usually showed porn. (There is a whole genre of lurid real-world footage of atrocities presented for entertainment.) As footage of Japanese civilians with their skin peeling off played on the screen, the audience of Americans was laughing hysterically as if they were watching Charlie Chaplin or the Marx Brothers.

For Chomsky, the experience was so disturbing because it showed that his fellow Americans could become so unmoved by the suffering of others that they could watch footage of the worst atrocity imaginable and enjoy themselves.1 To see this total lack of empathy in perfectly normal, “freedom-loving” people was frightening. It is one thing for people to not realize what it means for their country to have dropped nuclear weapons on civilian populations. It is a whole other level of depravity to be able to see the results and laugh.

In our interview, I also asked Chomsky if he remembered where he was when he found out about the Hiroshima bombing itself. He said he recalled the moment vividly: he was a junior counselor at a summer camp, and an announcement was made that the United States had just destroyed a Japanese city with an atomic bomb. Chomsky says that he experienced a “double terror”: first from the realization that we were now in the age where cities could be destroyed with nuclear weapons, and second from the response of those around him at the camp: they barely reacted, and quickly went back to playing games.

Chomsky has published over 100 books, and one of the themes that comes up again and again is the tragic apathy that people in the U.S. show toward the consequences of our actions for non-Americans. The invasion and occupation of South Vietnam killed millions of Vietnamese people, but it’s still treated in this country as a kind of noble mistake. The Biden administration is currently starving the people of Afghanistan to death. It’s hardly discussed in the media, and as a result, nobody seems to care.

If you are a person who is sensitive to the pain of others, and who does not discriminate morally between Americans and non-Americans, the U.S. can seem a downright perverse place. Donald Trump might be elected president again, even though his climate policy (which can be summarized as burn as many fossil fuels as possible) will result in the spread of death and mayhem around the world. The architects of the Iraq War, from public intellectual Bill Kristol to George W. Bush himself, are seen as respectable and even moderate. Ronald Reagan, routinely voted the greatest American president, “turned Central America into a killing field.”

Part of the problem is that the U.S. is geographically isolated from most countries that fall on the receiving end of its foreign policy decisions, a kind of cocoon, where most people have never had to see the aftermath of a city being bombed. Despite the undercurrent of violence in American life domestically—the police killings, the prisons, the shootings—the country has not had its cities ravaged by war like so many others. This may be why we do not really grasp the full extent of the horror signified by phrases like “children killed by a drone strike.” Even when foreign policy consequences are covered by the media, pictures on the news are carefully censored so as not to be too disturbing, and Central Americans, Iraqis, Afghans, Yemenis, etc. become a distant abstract Other whose pain doesn’t register. In the press, there is a straightforward hierarchy of lives, in which European and U.S. victims of crimes and natural disasters are given far more attention than African, Asian, and Latin American lives. U.S. policy and drug consumption has fueled monstrous violence just over the border in Mexico, but things that happen on the other side of the border might as well be happening on a distant planet for all the attention they get in the U.S. press.

One of the most important facts to understand about atrocities is that to the people perpetrating them, they often don’t seem like atrocities at all. Chomsky quoted a passage from John Stuart Mill, who condemned other countries’ violent interventions in global affairs, but thought the British empire was a shining exception, and the British were an angelic people whose colonial conquests were conducted for the benefit of the colonized. Chomsky commented that if even John Stuart Mill, the most morally sophisticated intellectual of his era, could not see through the dehumanizing racist myths used to rationalize imperial conquest, we can see why those contemporary American intellectuals Chomsky calls “not fit to shine Mill’s shoes” are similarly oblivious.

In fact, if you are not a member of the group on the receiving end of particular acts of subjugation and oppression, it can very difficult indeed to see through the stories that are told to justify that subjugation and oppression, or to find the ugly facts that are kept out of the mainstream. Americans still do not really understand the truth about what our country did in Vietnam and Central America, let alone Afghanistan and Iraq, just as Brits generally still think their empire was something noble to be proud of. Most of us in our everyday lives don’t run into people like, say, the maimed victims of the U.S. bombing campaign in Laos, so nobody thinks about it.

One of the reasons reading Chomsky was life-changing for me as a teenager was because he helped me see the world, and my country, through fresh eyes—the eyes of someone who valued every life equally and wondered how American actions looked to those on the “other side.” When you start thinking this way, things many accept as normal come to seem deeply disturbing. Here, for instance, is a photo of a U.S. training camp for soldiers being sent to Vietnam:

As you can see, the sign has a horrible racist caricature of a Vietnamese person who has been shot. But to the soldiers, the sign is perfectly normal. They aren’t horrified by it, or if they are, it does not stop them from continuing on their course. (U.S. soldiers were systematically trained to dehumanize the Vietnamese, to the point of always using racial slurs rather than the word “Vietnamese.”)

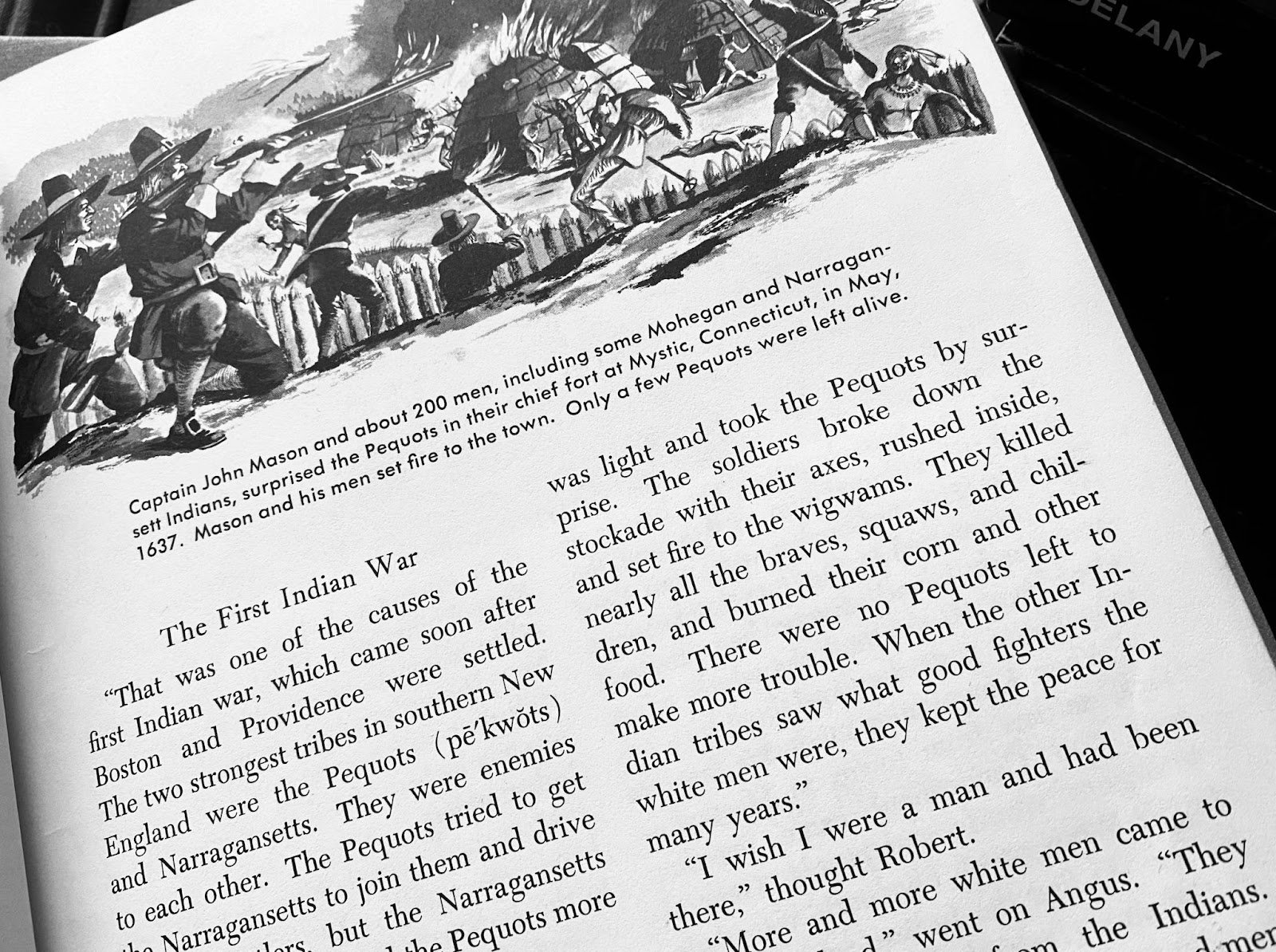

Chomsky once quoted a disturbing passage from a textbook that his children were assigned at school, in which the Pequot massacre was described as a benign or even exciting event in American history. I actually found an old copy of the book (Exploring New England, 1961) so I could see for myself. In it, a little boy named Robert who is being given a guided tour of New England history hears about the massacre and thinks: “I wish I were a man and had been there”:

Textbooks have had white supremacist assumptions built into them for generations, with the incredible violence of European colonialism simply left out of historical instruction. Since the 60s, when members of marginalized groups rose up and began demanding that subjects like Black history and women’s history be treated seriously, there have thankfully efforts to correct the propaganda, to tell a “people’s history” in which thieves and enslavers are not the heroes. The 1619 Project, for instance, is an effort to tell the truth about the ugly, racist parts of American history, and to teach the story of the country with Black lives mattering just as much as white lives. It tells us something that this rather mild attempt to show the basic facts of what happened has been met with a massive right-wing backlash. The Trump administration launched its own 1776 Project in a desperate attempt to keep history well-whitewashed.

One of the facts I return to again and again is that in Nazi Germany, the most hideously psychopathic racist society in human history, many perfectly ordinary people thought that their society was good and decent. In fact, Heinrich Himmler once told a group of SS officers that they ought to be proud of the fact that they had been able to “remain decent” while conducting an extermination campaign. Robert J. Lifton, author of The Nazi Doctors, talks about how the killer doctors of Auschwitz almost had two selves—a concentration camp self carrying out killings and a perfectly ordinary family self back home. A book called They Thought They Were Free shows how many “ordinary” Nazis saw themselves, and why they had trouble recognizing that they were not on the side of good, but of evil.

The fact that should disturb us all is that those who do the worst things imaginable often think of themselves as engaging in praiseworthy acts. The brutal British empire, the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the current Russian invasion of Ukraine—in each case, the perpetrators think of themselves as acting rightly against an evil enemy. If there is ever a war that ends all of human civilization, one thing we can predict with certainty is that both sides will see themselves as fighting for the cause of justice, even as each commits genocide on an unprecedented scale.

Philosopher David Livingstone Smith, in a valuable critical review of Rutger Bregman’s Humanity: A Hopeful History, says that one problem with human beings is that while we are generally “ultrasocial” and “disinclined to do violence to others” we “have developed cultural practices for short-circuiting our gut-level inhibitions against perpetrating such acts.” I reviewed Humanity: A Hopeful History myself—it argues that human beings are generally sociable and generous rather than malevolent. Livingstone Smith points out that, even if this is true, we can easily dehumanize each other in ways that make it essentially irrelevant. War is an act of sociability and solidarity: nobody is more altruistic than the soldier willing to die for others. But soldiers can be brave and selfless even in defense of absolutely horrifying causes. The building of the atomic bomb was a giant collaborative, cooperative project to try to build a genocide machine. Within a society, we can see abundant kindness and love and compassion, but that society may still be unleashing utter destruction on those unfortunate enough not to live within its borders or be within its empathy circle. The British could only see how they looked to each other, not how they looked to Indians starving to death under their rule. Even history’s worst monster, Adolf Hitler, did not think of himself as a bad man.

Is American society psychopathic, then, for its indifference to the suffering we cause? Not uniquely so. But this country does have a long record of violence to ignore—in fact, the whole country is built on violence and maintained by violence—and we are just as reluctant to apply serious self-scrutiny as Vladimir Putin is to question his bizarre fantasies about the need to “de-Nazify” Ukraine. We have an obligation to morally awaken ourselves and those around us, to “get woke” and start caring just as much about the victims of our own crimes as we do about the crimes of others.

We need to start noticing the “normalization” of the atrocious. Chomsky has cited a Vietnam-war era instance in which a children’s museum offered an exhibit where patrons could simulate attacking a Vietnamese village. This insane simulation of psychopathic destruction was installed by people who probably had no qualms about it—normal Americans who loved their families and believed in Freedom. I was similarly disturbed when I went to the National World War II Museum, where one can buy Iwo Jima playsets for kids and simulate one of history’s most horrifying orgies of bloodshed, joyfully massacring the Japanese. It is our job, when we see such things around us, to feel like Chomsky in that 1950s movie theater, to keep our empathy alive and not let the indifference of those around us justify lapsing into apathy ourselves.

Although note that some of this apparent enjoyment may have come from the fact that this event was public, and people feel pressure to appear to enjoy things those around them enjoy. ↩