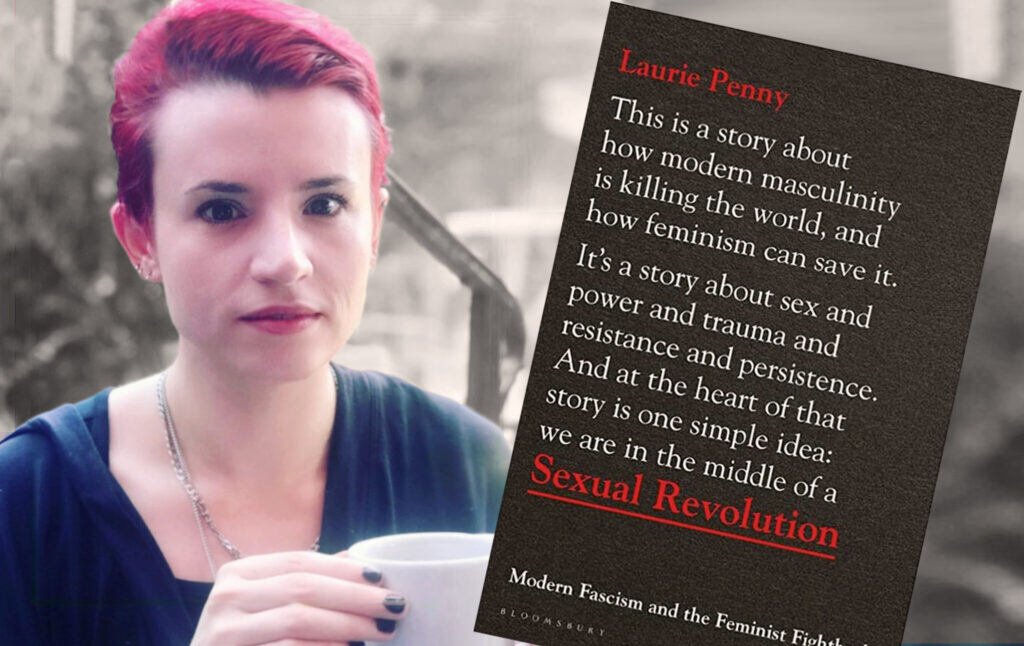

Laurie Penny on The Sexual Revolution

While gendered power dynamics have changed over the last several decades, Penny argues that gender relations have been framed by the logic of the market, which conflates nominal choice with liberation.

Laurie Penny is a journalist and activist who has written seven books including Unspeakable Things: Sex, Lies and Revolution, Bitch Doctrine: Essays for Dissenting Adults, and most recently, Sexual Revolution: Modern Fascism and the Feminist Fightback. Penny came on the Current Affairs podcast to talk to editor in chief Nathan J. Robinson about the “sexual revolution” of Penny’s book. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity and grammar.

Robinson

I thought we could start with the positive, before we get to pervasive sexual authoritarianism and patriarchy. In many ways, your book celebrates changes that have occurred in the last decade. You’ve been a political writer now for over ten years. There are positives in the world. You point out the increasing visibility of queer, non binary, and trans people these days, and the #MeToo movement. The book is about a sexual revolution taking place now, about women asserting autonomy and demanding consent.

Penny

It’s about a sexual revolution that is already happening. That’s the key. And thanks for opening with that—it’s one of the hardest things to get across to people. This is an exercise in pointing out the obvious. There is a slow-moving sea change happening in gendered power relations. It’s been building for decades now. And it has to do with economics; it has to do with imbalances and rebalances in structural violence and how power is organized and operates. And the reaction to that sexual revolution explains a great deal of modern politics.

It’s surprising to me that it hasn’t been directly named. The rise of the far right around the world, particularly around the global north, the rise of misogyny, and changes in how progressive politics are countered—a lot of that can be explained as a reaction and a backlash to the enormous changes in relations between the genders and in economic relations, which are experienced in very gendered ways.

This is one of the things that I point out in the book: a lot of the changes in people’s lives—even if you just look at millennials, and how our expectations in life have been very different from how our lives have turned out—are not, at their root, problems of sex and gender, but they’re experienced in highly gendered ways. American Twitter is great for concisely naming political phenomena, like the idea of the “failson.” I find it absolutely fascinating. Hundreds of thousands of young men are failsons. They’ve just had this failure to launch. They’re people who in previous generations would have found their niche; they would have found a job they could tolerate that would pay them a decent amount; they would have found a place to live; they would have been able to form relationships. But there’s just this sense that there’s no longer room or opportunity in their lives to access all of the things that they’re still raised to feel entitled to, some of which are things everyone should be entitled to. That’s an economic issue experienced in highly gendered ways.

Robinson

So these are young men who essentially don’t live up to what they feel like they ought to have. Perhaps they achieve a lower level of status than their parents did. And they experience that as a kind of humiliation. And then they desire something that will affirm them as important or give them some sense of power.

Penny

Absolutely. Status, pride, and dignity. Neoliberalism does not make room for the concept of human dignity. And that is an enormous problem especially among centrists and traditional American liberals. One of the reasons that they found it so hard to understand Trump is that what Trump offered a certain kind of person who voted for him was pride and a reason to feel that their dignity mattered. There were all kinds of toxic heuristics behind that. But the fact is that everyday life under late stage capitalism—which I insist on saying, even though it annoys people so much—but our lives and the lives of young and not-so-young men under late stage capitalism, are full of indignities and everyday humiliations. And so the one place they feel they can control or demand a restoration of status is in their relationships with women and within sexuality, which has become incredibly freighted by this howling vortex of straight male need. It’s about politics, and it’s about gender. I was trained as a journalist to think that those were two separate things. You had your political writers, and then you had the people who wrote for the women’s pages. And that has actually gone away—not so much with the women’s section anymore. But it’s almost like the politics of sex and gender are real politics.

You asked me about what is positive about the sexual revolution. A great deal. If you look at women’s lives and the real options that women have today, even a generation ago, those things were just slightly out of reach.

Robinson

Well, let’s go a little deeper. You said there have been profound changes in relations between the genders. Could you describe what you think are the most important of those changes?

Penny

There are enormous economic and social changes happening in the balance of power between men and women in most parts of the world. (When I say men and women, I am referring to political categories, the broad gender binary.) Let’s take an example. One thing that lawmakers and news outlets are suddenly paying attention to in an extremely panicked way is the plummeting birth rate across the global north and beyond. Birth rates have been dropping steadily over the past several decades. But over the past seven or eight years, they’ve really started to go down very fast. And in the last two years, they just fell off a cliff because women are not having babies anymore. And there are lots of reasons for that. I find it amusing reading. Some articles attempt to be objective about this, the collapse in birth rates and the change in women’s employment—that’s the way the BBC and the New York Times put it—increasing opportunities for women at work, as if the only reason that women weren’t having babies was because they would rather have a career.

But there are other things that have changed. The first thing that has changed is that it is much, much more expensive to have a child right now. Everything else in most people’s lives is much more expensive for millennials, who are the people who are actively not having babies right now. Most millennials have debt. They are not able to afford secure housing; there is no such thing as a secure job. Meanwhile, the costs of child care, education, and health care are going through the roof. People can barely afford to support themselves. What was the one thing we all grew up being told if we were a socialized female? Don’t have a baby you can’t afford. That was the message of ‘90s liberal anti-welfare ideology. If you can’t afford a baby, don’t have a baby. Well, many of us listened and lo and behold, it’s a problem because society is meant to collectively afford to raise children.

But the other big reason that women are choosing not to have babies is that more and more women are choosing not to be in long term relationships with men. The number of single women in America is higher than the number of married women, at least for the first time in history if you treat anybody who’s not literally married as single, which a lot of the statistics still do.The reason for that is that women can walk away from men now. It is no longer essential to a woman’s economic survival, or the survival of her kids, that she form some sort of partnership with a man. And for most of recent human history—particularly under capitalism—women’s dependence on men has been a basic artifact of our economy. And now it isn’t. Now in many, many cases, you’ll be poorer, perhaps, if you try to raise a kid on your own. But the difference won’t be that much, especially considering what you have to give up. And a lot of women are just walking away. That is one change that people are contorting themselves into to try to prevent.

Robinson

An analogous way of thinking about these kinds of shifts in power is employment. Employers complain that if unemployment benefits are generous, then all the workers start making demands because they know they can quit. So when the prospect of poverty is not the alternative—when it’s not work or starvation, but it’s work or doing something else—then people are able to make demands, and it changes the power relationship between the employer and the employee. Not to say that all marriages are employer-employee relationships…

Penny

Well if you were saying that, I would agree.

Robinson

But it used to be the case, right? So women are now in a position to raise their expectations and make more demands. They’re not forced into marriage because they have an alternative.

Penny

Absolutely.

Robinson

And this is why conservatives complain that Western civilization collapsed when no-fault divorce was introduced, because it actually meant that women could evaluate their marriages and decide for themselves whether they wanted to stay in them.

Penny

Absolutely. And if you consider Western civilization to be a certain form of patriarchal assumption, then yeah, it did collapse. A hundred percent. I’m writing a piece about this. And that is entirely correct. I believe that the collapse in birth rate is the real “great resignation” that has been happening for even longer than it’s been in the headlines. Lower paid workers all over the world are just walking out of their job saying, This is not worth it. If I’m going to be paid this pittance, I would rather not work in an Amazon warehouse. Exactly the same thing is going on within heterosexuality. It’s the “great resignation.” Women see that one has to spend their entire life looking after a husband, children, and anybody else who was around who needed looking after. And now the additional requirement is that one also work outside the home for money. So if one looks at how exhausted the women one knows are or at one’s parents or grandparents, one could say, I’d rather not.

Robinson

You also write a lot in the book about not just long-term marital relationships but about sex and consent, the way women are beginning to demand meaningful consent…

Penny

Absolutely.

Robinson

In which the sexual relationship has changed from something that men feel they are entitled to. And this causes a great backlash and consternation for many men, the idea that they might have to empathize with or convince someone to go to bed with them by making it something that the other person would enjoy, which was not necessarily previously the case.

Penny

Absolutely. I wouldn’s say that sex has forever been thought of as something that men just impose on women and women sort of put up with. But honestly quite a lot of modern heterosexuality—even the most explicit mainstream porn does make that assumption, which is you know, you can have people doing full frontal, you know, multi-orifice pornography, but it’s still essentially conservative. It’s very conservative if its base assumption is that sexuality is something that men do to women and that’s the only way that that relation goes. The logic of heterosexuality under neoliberalism one of exploitation and extraction. And a couple of times in the book, I call this sexual neoliberalism as opposed to actual sexual liberation. Because in modern, straight culture, I keep saying heterosexual culture, too, because heterosexuality is the oily water we all swim in. But I do think there are subtleties and differences in particularly the experience with people who are gay or bisexual. But homosexuality is still experienced within a broader world of heteronormative power relations. But within heterosexuality, we’ve mistaken sexual license for sexual liberation, in exactly the same way that we’ve mistaken the free market for actual freedom. Actual sexual liberation is not something that most people can afford, even if it’s allowed. You or I technically could buy a giant mansion. And—what’s the stupid thing you would get if you had millions and millions of dollars?

Robinson

Oh, gosh, fancy dressing gowns, I don’t know.

Penny

Fancy dressing gowns! Nothing is stopping you from having a fancy dressing gown for every day of the year.

Robinson

Other than a leftist magazine editor’s salary. Yes.

Penny

But nothing is stopping me from buying a giant mansion and filling it with things. Basically half the queer people I know need to have the same alternative to the white picket fence dream, which is either, I’m going to beat get a big house and it will be a commune and a safe space for queers, and nobody mean will be allowed to come in, or the version of that which is, I’m going to have a bookshop, and it’s also a cafe. It’s a safe space for queers. And nobody’s stopping me from doing that right now apart from the fact that I can’t afford to.

Robinson

I have no money. Yeah.

Penny

Exactly. And this is the difference between liberation and life under neoliberalism. Gender relations have been collapsed into the logic of the market. That is interpreted as freedom when it isn’t.

Robinson

I think the idea of sexual neoliberalism is fascinating. So just to draw out the parallel, the leftist critique of the market starts with the notion that you are nominally free to enter into whatever exchange you like. No one actually drags you into it by force. But underlying all of that, there are still some people who have power over others, and these power relations are disguised under the market. So the the parallel would be that in the world of sexual relationships between people, obviously, there’s plenty of actual coerced sex, but even plenty of sex that is not coerced still occurs in this environment where what looks like choice has power behind it. And that’s even true in the case of sex work. It can be freely chosen. But it depends on the alternatives that people have. That’s how you evaluate whether there’s exploitation occurring: what alternatives do people have? And when you evaluate power in sexual relationships, you’re thinking, well, do people have real meaningful choice here, even if they have nominal market choice?

Penny

That’s a really, really good way of summing it up. But you started out saying, well, nobody’s coerced into this stuff. And then you corrected yourself. And I’m like, that is also true in the world of work, because…

Robinson

Nobody’s coerced, but they are coerced.

Penny

Yeah. The fact that some people are coerced is essential to that logic, because it’s like, well, at least I’m not being coerced. So when you’re working for this low wage in America, and you’re paying off your student debt, you’re thinking, well, at least I’m not in prison being forced to work for nothing. Britain has its own issues of exploitation. But I was really, really shocked when I found out just how many people in prison were being forced to work for nothing for private companies in the United States. There’s a lot of people outside the U.S. who simply don’t know that that’s going on. It’s one of those things that outside America, people just wouldn’t think that that would happen. And within the U.S., people just assume it’s normal. Like your healthcare system, all the guns. Americans don’t seem to know [that this isn’t normal].

Robinson

You know, the U.S. Constitution explicitly legalizes slavery in prison. The 13th Amendment says that slavery is abolished, except as if you’re convicted of a crime.

Penny

Yeah, exactly. Within sexual neoliberalism, the analogy really does extend because in many ways, it’s not an analogy at all. It’s the same imposed market relation. If your baseline of what a non exploitative relationship should look like is, well, at least I’m not being raped and beaten, then… I don’t know if you’ve ever seen someone say, “well, you know, he’s a good guy. He’s never hit me.” Well, that’s great. But it’s like saying, “This is a good boss. Sometimes they let me go home.”

Robinson

The bar is very low.

Penny

Yeah, the bar is on the floor. And actually, #MeToo movement was in some ways a reaction against women saying: What if let’s not rape each other wasn’t the gold standard? But what if that was the baseline? Can we do better? In the same way that the great resignation in terms of sexual power relations is women walking away from marriage, walking away from something that doesn’t serve our interests, walking away from motherhood, but also walking away from shitty dreadful sexual relationships. It’s not a demand that all men be some kind of like … Whenever I try to describe an attractive man… Have you ever seen Brooklyn Nine-Nine?

Robinson

No.

Penny

Oh, it’s wonderful. There’s a character Captain Holt, who is gay and head of the precinct who occasionally has to go undercover as a straight man. And he will describe a woman he has found attractive as, “Yes, she has very pendulous breasts.” Even though I fancy boys, whenever I try to describe an attractive man, I sound like that. I sound like I’m saying, a ripped, Adonis-looking man with many muscles. Like I don’t know what I’m talking about. But anyway, the demand for better sex isn’t a demand that all men everywhere suddenly become some sort of 18th-century Casanova. It’s just sex where you’re treated like a person.

Robinson

Right. The idea that people care about each other and each other’s pleasure. You’ve convinced me of something. You say in the book that sex parallels a bigger political project of building a society where people care about what happens to each other, and that we need to not keep accepting the idea that mere consent means that nothing has gone wrong.

Penny

Exactly.

Robinson

Because that is neoliberal thinking, right? That’s what libertarians say: Well, you signed the contract. So now you can’t complain.

Penny

You accepted the terms and conditions. Yeah. Exactly.

Robinson

You accepted the terms and conditions. But what we’re advocating is something where you say, No, it’s more than just technically entering into—in the most limited sense—a free exchange. It’s thinking about people’s desires, their fulfillment, and they are entitled to be dissatisfied if all of their intimate relations with other people are unsatisfying and unfulfilling and uncaring…

Penny

Absolutely. And even when that dissatisfaction veers into hateful arenas, the basic feeling that the way we treat each other could be better—and could be far more fulfilling—is not wrong. I think it’s getting worse. The language of heterosexuality more and more emotionally cauterizes masculine desire in the way that all emotions are meant to be reduced into the key of anger. All sexual desire is meant to be the sort of desire to dominate and own and conquer and penetrate. And it’s very limiting. There have been some really good books lately by people like Peggy Orenstein. I met her once; she’s a fantastic woman. She interviewed hundreds of young men including frat boys and asked them what they really thought and felt about sex. One of the things that these studies have found is that a lot of young men are really scared and unhappy at the kind of sexuality that they think they need to perform in order to access any intimacy, particularly when for men in general, sexuality and sex with women is the only way they’re allowed to want to be touched.

Robinson

You talk a lot about fascism in the book, and you talk about the way in which the demand by women for real autonomy, for accountability, for misbehavior, for real consent—and not just formal consent—leads to this horrific backlash that could be embodied in, well, obviously, the President of the United States and the Prime Minister of Great Britain…

Penny

The former president of the U.S.

Robinson

He’s coming back. But yeah.

Penny

Oh God. Yeah.

Robinson

Biden also has sexual misconduct allegations. Trump is the one who brags about it. He doesn’t deny it. Which is to say, “Yes, I did. Because I have an entitlement.” You write about that ideology of entitlement.

Penny

There was that moment about a week before the elections in 2016, when the Access Hollywood tapes came out, and everybody heard Trump bragging, you can just “grab her by the pussy.” You can do whatever you want. And liberals and nice centrist people around the world thought, Oh, well, he’s done now.

Robinson

Yeah. I did.

Penny

But I didn’t think so. But I didn’t think he was gonna win anyway. And I was proven very, very wrong. So I’m not coming to it from some great wisdom. But people thought, Oh, he was elected in spite of it. He was elected even though those tapes showed him bragging about being a sexual aggressor. He wasn’t elected in spite of it; he was elected because of it. He said the quiet part out loud. That’s the kind of entitlement that is valorized. Now people say, actually, we want to grab what we want. That’s what strong powerful men do. And that’s what we want our leaders to be able to do. Boris Johnson—exactly the same. The idea that you’re entitled to a certain kind of service from women. And that real strong, powerful dominant men—patriarchs—should be able to just take what they want. Like you’re the ultimate silverback. And the idea that that is synonymous with abuse. Within the #MeToo movement, and afterwards, the outrage from men and from people defending the sexual status quo wasn’t that firstly, Oh, my God, there’s been so much violence that we didn’t know it was happening. The outrage wasn’t even that we’re being shown things we didn’t want to know about. The outrage was about the fact that people were saying it was a problem. Everybody knows it. We don’t talk about it, mostly because it’s not polite. Why is this a problem now? It’s never been a problem before. Well, actually, it was a problem before, but as we already said, when you’re in a situation where your well-being and your economic survival depends on not pissing off the powerful or relatively powerful men around you, you’re not going to complain. You’re going to put up with as much as you can. It’s risky.

Robinson

I feel like an example of this is the popularity of Jordan Peterson, who became famous, essentially, because he refused to use people’s preferred pronouns. He drew this line in the sand and said, I will not do this. He also explicitly advocated what he called dominance hierarchies. Organize our society like lobster society, where we just have these powerful men on top.

Penny

I’d forgotten the lobster…

Robinson

Yeah, the lobster is a big part of it.

Penny

Lobster daddy.

Robinson

Essentially his argument is that now there are suddenly all these new demands being placed on me, like people’s pronouns. Why these unreasonable changes? And the answer is, well, before, you didn’t care about people, and now you’re being asked to. And then you see that as this incredibly confusing challenge to everything you thought…

Penny

Oppressive. There is an economic and class logic to the idea that caring about other people is for suckers. There’s that line—let’s find and attribute the person because I know the person who came up with this line has not been credited enough1—but the line is, I don’t know how to explain to you that you should care about other people. And I’ve been doing a lot of research into the social history of Victorian England, and how much of the logic and cultural weirdness at that time is in the DNA of our culture now. The intense social hierarchy of those times mandated that most people in society who were members of the working class—or the serving class, there were far more servants back then than anybody realizes—you had to be polite. You had to care about other people as that was your job. What you aspired to be—or you knew you never could be good enough to be—was the kind of person who doesn’t have to care about anybody else. An aristocrat is somebody who, by right or might, doesn’t have to care about other people.

That’s how gendered power relations are also increasingly organized. The work of caring for other people is feminized, both when it’s paid and when it isn’t. And that work is considered for the suckers. Only women do that. Women care about other people so that men don’t have to, because to care about people would be seen as weak or gay. You see that with the reactions to mask mandate or even just masks suggestions, the idea that just mildly inconveniencing yourself in order to protect other people from a potentially deadly disease is an unacceptable intrusion into your personal freedom. Just being asked to use someone’s correct pronouns or to call somebody by the name that they choose. That’s the requirement that you treat other people with basic consideration. If you think that that is the greatest possible attack on your freedom—well, firstly, you don’t understand what oppression is or you’ve never experienced it. It is a wild attitude of toxic individualism—and the fact that rugged individualism was only ever meant to apply to men.

And how many of the same people who are saying, Oh, I shouldn’t have to inconvenience myself for other people, I hate wearing a mask, are the same people who are, ironically, trying to make it illegal for women to not carry an unwanted pregnancy to term, which is more than a minor inconvenience? Just have the baby and seek adoption. That is really doing a lot of work there. And that’s an old, old idea, in new terms, the idea that women should suffer—it’s in the Bible—that women’s suffering is somehow natural and normal and good and women ought to suffer so that men can enjoy a certain kind of freedom.

Robinson

That’s a really important comparison. The argument that is made is that bodily autonomy is violated if you make me get vaccinated, even though what’s being “bodily autonomy” would end up killing other people, right, by giving them a horrible deadly disease? I have a right to infect and kill people. But then why doesn’t bodily autonomy apply to abortion? Oh, well, your bodily autonomy is nothing compared to the life of the fetus because we really care about protecting life. Just not about taking life by giving everyone coronavirus.

Penny

Exactly. There’s a whole other podcast to talk about moral panics and notional children, who are so much easier to fight for than real children. But that is the idea, the idea that only women should be expected to make sacrifices for other people, that the basic work of care and of social reproduction and of looking after other people is something that women should be forced to do even at the cost of their own lives. And it tallies absolutely with the destruction of social welfare, with the fallen wages and the idea that women’s bodies are meant to be the safety net that allows the rest of society to continue. They’re meant to be the baseline communism that David Graeber talks about. There’s a baseline communism in society without which even the most strictly capitalist economies wouldn’t function. People do help each other. But now even just basic considerations for others are now considered foolish because you’re not profiting from that. So you’re a sucker. Unless you’re a woman, in which case, you should be legally mandated to do that work. Otherwise, you’re evil in some way.

Robinson

There’s one last thing that I wanted to bring up, which is that there’s one way that we could respond to this, which is by saying that, well, women should get to be sociopathic individualists, too. Women should get to rise to the top of Wall Street and emulate all this horrible behavior. It’s not the path that you go down. I think one of the things that may surprise people about your writing is that you try to muster a deep empathy even for the people you completely despise. There’s righteous anger right at sexual authoritarianism, but you’ve even attracted a controversy for your willingness to try to understand the followers of Milo Yiannopoulos.

Penny

Oh God. Yeah.

Robinson

To try to see everyone, even oppressive people, as human beings. To try to understand the ways that patriarchy destroys men, and that their lives are ultimately empty and unsatisfying and pathetic. It’s not to say that because there’s this baseline communism, women shouldn’t have to be empathetic and kind; it’s to extend the demand and say, We need to build the kind of society in which everyone cares about each other’s pleasures and desires.

Penny

There is enough caring work to go around, it’s just not evenly distributed. Thank you for mentioning empathy. For me, that kind of empathy is not about morality; it’s about strategy. You try to understand people who are behaving horrifically, not because you condone them, but because you want to know what they’re going to do, why they’re doing it, and how to stop them from doing it. And that’s partly because I’m an airbender (Avatar: The Last Airbender). My fighting style is magic, magic, conflict avoidance. I’m aware that that’s not everybody’s attitude. I’m also female, I’m white, and I’m physically tiny. I’m five feet tall. I’m also quite a timid person.

So my model for conflict avoidance or my way of protecting myself is considering, What if we were all a bit nicer to each other? And maybe if I try to understand people, they’ll understand me, but also because I’m a tiny white lady, that actually works for me. It wouldn’t work for everyone. “Oh gosh, don’t hurt each other.” Not everybody gets to say that and not be considered ridiculous. I think that’s a shame.

So for me, the way I have protected myself in past situations that were dangerous or scary is by trying to empathize, trying to understand what the other person is feeling so I can predict their reactions. And that’s not approval at all. That’s threat modeling. And my threat modeling is empathy. For me, it’s a strategic way to think about it. But I do think empathy of all kinds, including cognitive empathy, is politically useful. It doesn’t mean that you extend sympathy. You extend compassion and mercy.

That doesn’t mean you don’t hold people to standards. There is a fallacy that showing empathy, or even just trying to understand somebody’s point of view, means letting them off the hook. And it means indulging them and not creating consequences. And that comes from how many of us—white men in particular—have often been treated down the centuries. White men are the only people who are allowed mercy and forgiveness and tolerance and understanding. And actually, I think everybody should be offered all of those things and be held to expectations of behavior. And just because women should not be forced or coerced into the work of social reproduction doesn’t mean that we don’t need to do social reproduction. We all need to do it. That work needs to be distributed more evenly. Somebody still needs to take care of old people; somebody still needs to clean the house. Somebody needs to do all of those things. And actually, it’s not about not doing that work. It’s about making sure that that work is valued differently and distributed better. I wrote a book called Sexual Revolution and it’s about fascism and sex. It doesn’t sound like it’s gonna be as much about the economic implications of who does the dishes, but it is largely about that.

Robinson

The book is Sexual Revolution: Modern Fascism and the Feminist Fightback, available from Bloomsbury publishing. Laurie Penny, thank you so much for talking to me today.

Penny

Thank you very, very much.

Lauren Morril, although the line was wrongly attributed to Anthony Fauci ↩