The Rise of Pentecostal Christianity

While the world’s fastest-growing religious faith offers material benefits and psychological uplift to many people, it also pushes a reactionary political agenda aligned with dangerous far-right leaders.

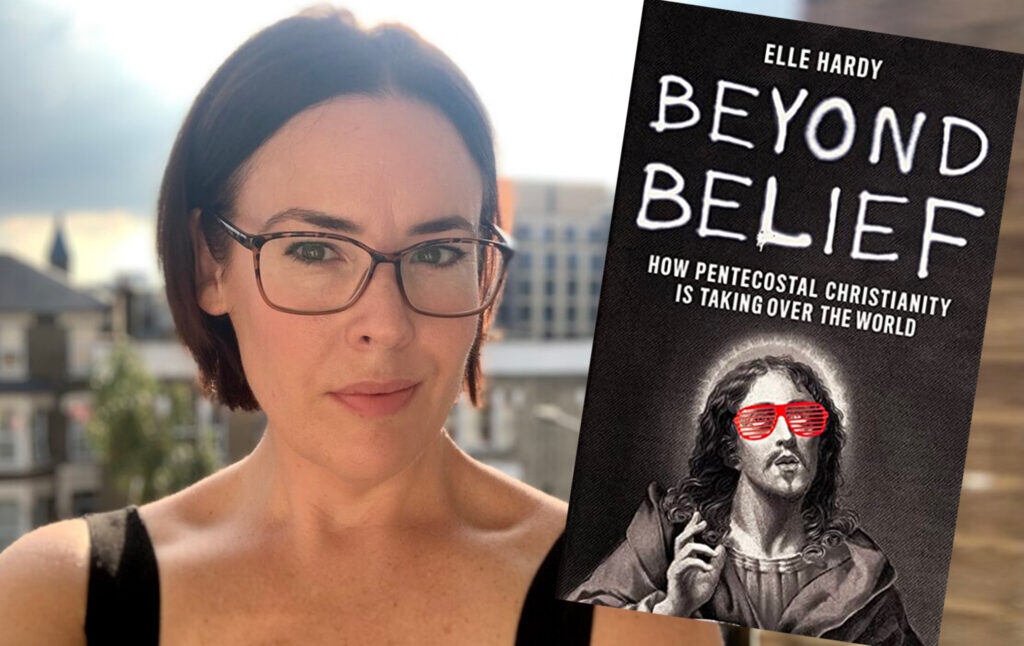

Elle Hardy is a journalist who has reported from all over the world and written for GQ, Foreign Policy, Business Insider, and Current Affairs. Her new book is Beyond Belief: How Pentecostal Christianity is Taking Over the World. The Sunday Times says Hardy is a “first-class reporter. Beyond Belief makes for an often gripping story full of twists and turns.” The Telegraph calls it an “elegant account” and says that Hardy is an engaging usher around the Pentecostal world. The Irish Times calls it a lively book and a useful introduction to the world’s fastest growing faith. She recently came on the Current Affairs podcast to talk to editor in chief Nathan J. Robinson about the rise of Pentecostalism. This interview has been edited for grammar and clarity.

Robinson

So, Pentecostal Christianity is taking over the world. For our listeners and readers who may not be familiar with the distinctiveness of the Pentecostal movement, which you have now studied in many different countries and many different U.S. states: What is Pentecostalism, and how does it differ from the rest of Christianity?

Hardy

The easiest way to think of it is that it’s a branch of evangelical Christianity. Or, as I call it, “born again plus.” First, like any other evangelical, you are born again. You accept Jesus as your Lord and Savior. Pentecostals tend to do full immersion baptism. But then Pentecostals are also born again into the Holy Spirit. So that means that they’re filled with the Holy Spirit, often by praying and hoping for it to come on. And it’s generally best known as speaking in tongues. That’s what Pentecostals are probably most famous for. So it often manifests that way, but also the Holy Spirit entering you gives you the 9 Gifts of the Spirit, things like healing and divination. And those things are also pretty important to Pentecostals.

Robinson

So not all evangelicals are Pentecostals but all Pentecostals are evangelicals. Is that right?

Hardy

Yeah. That’s the way to think of it for sure. We can get into some of the facts and figures a bit more, but we’re seeing in the U.S. a lot of churches calling themselves nondenominational, and that’s been led by Pentecostal churches. So it’s gonna be pretty hard to tell what they are. And you’re really seeing the influence of the Holy Spirit, which is the big Pentecostal thing, and all sorts of other Southern Baptists and all sorts of other churches, even Catholic churches. So you can’t always tell. A lot of churches don’t advertise themselves as Pentecostal anymore. But definitely any sort of spirit led charismatic church I broadly call Pentecostal because within the movement that’s fairly significant.

Robinson

Do they all speak in tongues?

Hardy

It’s probably becoming less common. It was certainly the big feature early on because in 1906 people thought that they were learning to speak in Chinese and setting sail for China and dying of dysentery and other horrible things by the time they got there because they were totally unprepared. So it’s not as common now and probably younger people at Hillsong churches and things like that might find it a bit weird. Often, people just have quiet communion with God. And some people might do more of a silent prayer but definitely some people love the tongues. It gives them something a bit more, and they really feel as though God is speaking through them.

Robinson

What is it, exactly? Is it a dead language or…?

Hardy

Yeah, there is some interesting research on it. It’s very difficult to tell. Often, it’s just a completely nonsensical language. People once thought that they were speaking in Chinese or Swedish and they would go out and evangelize these people. So because it comes from the Bible, that the Holy Spirit on the day of Pentecost descended on the disciples 50 days after Jesus rose from the dead, and was supposed to give them foreign tongues to speak so they could go out and make disciples of all nations. The original Pentecostals at the turn of the 20th century thought that they were doing that. These days it’s more thought of as probably your unique and private language with God, that the Holy Spirit tries to give you a message or you’re just communicating in some other language. So it can really mean different things to different people now.

Robinson

I am not a close reader of the Holy Bible. So that was new to me. The passage that it’s taken from—Mark 16: 17-18—says something like, Follow those who believe in my name, they shall cast out devils. They shall speak with new tongues. Then it says they shall take up serpents and if they drink the deadly thing, it shall not hurt them. So people take it literally, but some of them even take the serpents and ‘drink deadly things’ seriously.

Hardy

Yeah, that’s right. So it’s a fairly small movement within the Appalachians. They’re called With Signs churches; they’re the snake handling churches. In the book, I visit a fairly small congregation in Alabama that’s still practicing it. They do the rattlesnakes. I couldn’t do it because it’s more of a male thing. And they were out of poison, so I couldn’t drink the poison with them. They drink—I think it’s rat poison. I was just going to have a sip. But it’s kind of hard to get. You just can’t get it on Amazon these days, apparently. But yeah, they still practice that. Interestingly, someone in the congregation up there told me that they started doing that because in Prohibition times, the Christians were taking away some of the moonshiners’ business. And the moonshiners had started putting snakes in their things to try and run them out of town. I hadn’t seen that anywhere in the academic literature—the religious scholars are always going up there to study this quite bizarre practice. So one of these guys reckoned that it came from Prohibition times. And obviously, the biblical justification.

Robinson

In fairness, they’re taking the Bible very seriously.

Hardy

That’s right. Yeah. And they will get bitten a lot. The Alabama congregation was pretty upset because Alabama recently changed the laws that you can get picked up by an ambulance without consent. So when they get bitten they don’t really like to get picked up by an ambulance. You can pray it away, and your ability to heal reveals the extent to which you are a good Christian. So for them, it’s quite a profound moment, and they’re very upset with the new ambulance laws. If you get bitten in that church, no one’s going to be calling an ambulance too quickly.

Robinson

Yeah. It doesn’t specifically say in Mark to take up serpents without getting bitten. So it doesn’t promise you the snakes aren’t going to bite you.

Hardy

That’s right. Yeah.

Robinson

That’s interesting. Where does the word Pentecostal come from?

Hardy

It comes from the Bible, from the book of Acts. It’s sometimes known in some places as the seventh Sunday, the 50th day after Easter Sunday. So it was when the Holy Spirit descended on the disciples. And he descended on them in the form of the Holy Spirit and gave them this ability to speak in tongues, to go out to foreign lands and convert new people. These days, a lot of places don’t call themselves Pentecostal. They started being called Pentecostals in the 1910s-1920s. And they kind of took on that name. But these days, they’re so media savvy and so brand conscious that they deliberately won’t call themselves Pentecostal. They’ll call themselves Hillsong and have the tagline “one house with many rooms.” Or they’ll quite specifically be nondenominational but you can usually find out it’s a Pentecostal church through their references to the Holy Spirit and so they might be spirit led or talk about things in those sorts of terms. That’s what tends to differentiate them from other evangelical churches.

Robinson

I do want to discuss the ways that your book documents how these churches are adapting to the 21st century through being very social media savvy. But first, let’s go back. Where did this come from? This distinct Holy Spirit-infused sub-branch of evangelical Christianity?

Hardy

So it’s generally attributed to what’s called the Azusa Street Revival, which happened in Los Angeles in 1906. And it was led by the son of freed slaves from Louisiana, a man named William J. Seymour. He’s credited as the founder of Pentecostalism, although I think his mentor, who was a white man, probably has a better claim. His name was Charles Fox Parham, an itinerant Methodist preacher from Kansas. And he was practicing a lot of stuff that was coming around in 19th-century America, with frontier culture and all sorts of things that happened after the Civil War—whether it was women starting to preach or people perhaps angry with organized religion or things just changing and that real kind of wandering, conquering spirit that I think was going on in America. Some strains of new thought, like Ralph Waldo Emerson.

So it really emerged out of Methodism. And that’s where Charles Fox Parham really got going. He had a dispute pretty early, because he wanted to practice some of these new bents on really taking on the Holy Spirit, and speaking in tongues, and getting those blessings bestowed upon you that people started to talk about. This stuff had really died out a couple of centuries after Jesus. Things like speaking in tongues were really confined to the monastery for millennia, and people started bringing some of these ideas back. So he and a group of followers in Kansas were really interested in healing; Parham and his young son were both quite sickly. If there isn’t great health care now, there certainly wasn’t back then. So a group got together in 1901, they were fasting and praying. And the Spirit came upon a woman called Agnes Ozman, and she started speaking in tongues. And I believe that at the time, they thought it was Chinese, and they were mocked in the press. They said that this wonderful moment had happened, and they were called the Tower of Babel and really ridiculed. But Parham was a pretty headstrong dude. And he began taking it around Kansas and Texas and Oklahoma and preaching this new bent on faith. And in Houston in 1906, he met his protégé, William J. Seymour. Because of Jim Crow laws at the time, Seymour had to take his instruction out in the corridor while the white men sat inside. But obviously, they were very, very different men in every way. But they had something in common and saw something in each other, and they used to go out preaching on street corners. Parham preached to the whites, and Seymour would preach to the Black people, and Seymour was then invited up to a church in Los Angeles and pretty soon locked out, which always seemed to happen to Pentecostals—someone would lock them out. He had this huge moment. He had a group of followers then and they were praying and fasting for days on end.

And eventually the Spirit came to the congregation. And it was a huge moment. People were rolling around and filled with this ecstasy in quite a strange moment of faith. Los Angeles was a real burgeoning city; there were migrants coming from all over the country and all over the world. There was a very lively press. The same day that the news of the Azusa Street Revival hit the LA papers, the news of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake hit the papers, and a lot of people saw this as a sign that it was the End Times, and these guys seemed to have something pretty profound happening to them, and it just took off from there.

Robinson

Los Angeles is not necessarily a city associated with evangelical Christianity. There’s a lot fascinating about the history you’ve laid out here. Martin Luther King, Jr. famously said that the most segregated hour in American life is 11 o’clock on Sunday morning because of the deep segregation of the churches. But you’re saying that, in fact, the man considered the founder of Pentecostalism is a Black man, son of freed slaves? Does that mean that there is a direct line from the preaching of this Black man to the Appalachian snake handlers of today?

Hardy

There was obviously word of these ideas and a really fast developing and changing faith that was unique to 19th century America. But certainly, this word really spread out of Los Angeles. And one of the things that Seymour allowed from the beginning—and was quite headstrong about—was that Blacks and whites and all sorts of people were allowed to pray and would sit side by side in his church. Women were allowed to preach. And that’s always been a distinctive hallmark of Pentecostals from the beginning.

Worldwide, most of the preachers are men but often have very prominent wives or very prominent women within the ministry. It’s the faith of the working poor, especially in Brazil. It’s sweeping through Catholicism because your traditional priest in Brazil is probably a white man who has been educated in Spain or Portugal, whereas the Pentecostal preacher is a mixed-race person who came up from the favela. To this day, that is certainly something significant to people. I think that makes Pentecostalism feel more authentic to the average person, to have someone that looks and sounds like them and understands their lived experience.

Robinson

The current growth of Pentecostalism across the world is quite remarkable. Why would you be interested in this particular branch of Christianity? There are good reasons for this. As you say, it’s the fastest growing religion on earth. You cite some extraordinary statistics. By some accounts, 35,000 people a day are becoming Pentecostal around around the world.

Hardy

Yeah. There are about 600 million Pentecostals worldwide, out of about 2 billion Christians. I would venture to say that the number is probably higher. The Catholic church in Latin America had to do a special rebranding of charismatic Catholicism. There are other regions where Pentecostalism just seems to fit in well with local culture, particularly in parts of sub-Saharan Africa. But yes, 600 million people in the world out of about 2 billion Christians. You’ve got Catholic churches playing Hillsong music to keep people coming through the doors. One of the great not-so-secrets is that you don’t convert atheists, you tend to convert existing believers. In places like Brazil it’s going to overtake Catholicism as the dominant religion in the country in the next decade. Even in Nigeria, there’s a born-again, Islamic mosque, that is really having to incorporate Pentecostal practices into their Islamic preaching, because they’re losing so many young people, particularly to the Pentecostal churches.

Robinson

So how does a church Pentecostal-ize or rebrand itself in order to take advantage of the popularity of this new Christian movement sweeping the world?

Hardy

A lot of the big churches were originally under one of the umbrellas of Pentecostalism like Assemblies of God, so your Hillsongs and your Bethels and some of the big churches such as Universal Church of Kingdom of God in Brazil. But there, they all tend to be leaving those umbrella groups now because they don’t want any oversight. They really want to be their own brands. And as I talk about in the book, it’s bizarre but you see quite a lot of Silicon Valley influence and things like that coming into the mindset. Many of the big churches almost see themselves as CEOs of a morally charged business. Tithing and things like that don’t account so much for their fundraising as things like having their own colleges and selling do-it-yourself, at-home courses and things like that. If a church is wanting to Pentecostal-ize itself, it all depends on the preacher. It all depends on what direction that they want to go, but it probably would be taking more of a Holy Spirit-led focus again.

The Holy Spirit is really the main distinction here. So it’s like a more spirit-led focus. In some ways, that can look a bit different from traditional Christianity. It’s in many ways much more spiritual. This will sometimes attract more spiritual, but not religious, types of people. You’re even seeing some QAnon-aligned churches within the Pentecostal movement. So it really depends on the preacher. And, largely, it tends to just look and feel like the local culture. So there are Islamic mosques Pentecostal-izing in Lagos, Nigeria in order to cater to what people want. People might have grown up with one Muslim parent and one Christian parent. It really all depends on the look and feel of the local culture. But you’re certainly seeing a move toward the Holy Spirit being more improvised, often being quite more austere, without all the bells and smells and all the big things of Catholicism in the beautiful cathedrals. Often they’re very pared back. But that seems to have some appeal to people. All the money within the congregation is going to the preacher or back into the congregation.

Robinson

You mentioned the QAnon-aligned churches. So there are as many varieties of Pentecostalism as there are local cultures. But to what extent in your observations is this movement political? There are obviously certain religious sects that tend to shun political activity. And there are those that have strong political ideologies. What do you tend to see?

Hardy

It’s really quite profound, how political some of these churches are. In many parts of the world, it’s really the theological wing of the new radical right populists that we’re seeing. There was a huge movement behind Bolsonaro in Brazil, particularly on WhatsApp. I think WhatsApp actually had to change its messaging system so that you could only forward a message to 64 people at once after the Brazilian election. There was so much fake news going around about little boys being made to be gay at school, and things like that, that was really coming out of the evangelicals who are almost entirely Pentecostal in Brazil today. Duterte in the Philippines had a really prominent Pentecostal preacher behind him. The first evangelicals to get behind Trump were the Pentecostals. It was people like Paula White-Cain. Even Viktor Orbán in Hungary had a Pentecostal preacher behind him, and his son is quite a well-known Pentecostal preacher now as well. So it certainly really aligns with the radical right. We’ve all talked about it to death. But what it really has in common [with the right] is a real disdain for experts, the idea that what I feel is more important than what you’re telling me to think. That ability to fire people up at rallies, captivate an audience, and things like that.

Pentecostal preachers often have that in common with those sorts of politicians. In the West, we tend to think that everything’s getting more secular. People say to me that nones are the fastest growing religious group in America. But, this certainly isn’t the case in the rest of the world. I would say that they really feel that there is a liberal secularism that is corrupting the world. Gay marriage comes up all the time, climate change, feeling like people of faith are besieged by liberal secularism around them. There really is a big move in parts of the Global South, particularly Brazil and Nigeria, to re-evangelize the West. They say, Hey, you guys brought us the good news. And now you’re secularizing and you’ve completely fallen apart. Look at your societies—the gays getting married, Brexit—things like that are all happening and we need to help you get your faith back.

Robinson

So it is very socially conservative. Opposition to abortion, opposition to gay rights, cracking down on sex workers because of the noble concern for child trafficking.

Hardy

One of the really notable things about modern Pentecostals is that it’s a real shift away from your Billy Grahams and Jerry Falwells and your old-school evangelicals, some old white man yelling at you about abortion or whatever and saving your soul. Pentecostals don’t just want to save your soul; they really want to transform society. And they have this eerie ability to embrace new media, so they’re really really good at online stuff and social media. You see a lot of groups popping up. I have a whole chapter on this—air quotes—the “anti-human trafficking” movement and things like the John School Movement, which is reform class for men caught soliciting prostitution. There are private classes often run by different church groups, in cooperation with the state, obviously. I think Texas has a law now that anyone can start one or something like that. That’s so like Texas. And they’re completely unregulated.

But yeah, so you have a movement and it’s largely led by women. Some of the most prominent voices in this space are women. Young, savvy women who are leading this. They’re really, really interested in “girl boss” ideas. They’re certainly not feminists—they would certainly never call themselves that. They’re into having a moral entrepreneurship role. One of their main causes is being very anti-pornography and very anti-sex work. Obviously, we’re starting to see a lot more focus on picking on trans kids as well. They have these grand visions of society. It’s a rebranding of Christian dominionism. A lot of these groups do some good work, and they’re very modern and savvy. They might not be necessarily storming the local school board, but there are certainly some elements very inspired by some doctrines of Pentecostal thought who are really trying to transform things and manipulate ideas in quite opposite ways compared to what many people working in social justice spaces are trying to do.

Robinson

Dominionism being the sort of collapsing of church and state into the…

Hardy

The divine right to rule. This is obviously pretty prevalent in America right now. Many on the radical right of the Republican Party know that they’ve lost the battle of democracy and demographics. So it’s just really straight up Christian dominionism coming out of these guys in the form of the seven mountain mandate and spiritual warfare. You’re seeing it get picked up by Charlie Kirk. He was saying some of this stuff, and I don’t think that he’s particularly religious at all. But there are some of these divine right to rule mandates really coming through. These guys know that they’re a minority now, and it’s only a sleight of hand. They’re really just picking up anything they can and really firing up the radical right in the U.S. It just came out in the last 10 years by a really awful guy called Lance Wallnau. Now he’s the one whose sermons you can see on Facebook; he’s really preaching MAGA stuff most nights. Believers say that there are seven mountains or spheres of influence in society. So it’s business, governments, entertainment, media. There’s always one that I forget: most notably, education. And that’s where these guys get really, really fired up. So you’re seeing quite a lot of school board stuff, like in Colorado. People are trying to take over the school boards, saying that there’s no such thing as secular employment for the believer. So it’s really inspiring people to do anything in your personal power to basically employ Christian dominionism. They say that the world has been conquered by evil spirits, that the devil has conquered the seven mountains. Now believers have to take them back for themselves. And it really just appeals to that very conservative instinct and tradition in America. Democrats always want to be Obama, they always want to give the big speech, or whatever. Republicans are really good at stuff, saying, No, go into your school board and say, no more Harry Potter. And so it’s really appealing to that sort of sensibility that’s in a lot of conservatives and the religious right in the U.S.

Robinson

To what extent is this faith apocalyptic? Or does it believe in the End Times?

Hardy

I mentioned the San Francisco earthquake. That was really profound in Guatemala, which now might be the most Pentecostal nation on earth. But in terms of people in 1906, the earthquake really pushed people as well. So there was always that sort of trembling fear that the End Times are about to happen anytime. Back then, though, they were notably pre-millennialists. Now, most Pentecostals and probably most evangelicals are post-millennials. So that’s a pretty profound theological shift, because it means that they believe that they’ve got to create the conditions on Earth for Jesus to return to. So that’s when you get that real fixation with Israel. It’s quite bizarre. It’s almost totemic. I wrote a piece for Current Affairs on visiting the IDF fantasy camp a couple of years ago, where Jerry Seinfeld had visited and kind of got canceled for posing with these IDF commanders. And it was really interesting. I went with a group of American evangelicals, and the IDF guys were laughing at us. Why are a bunch of Americans coming over here to shoot things? You can do that wherever you want back home.

And the American guy who was running it was originally from Louisiana. He was saying, Oh, every Jew is a miracle. And we’re seeing miracles taking place all over the state of Israel. And I was thinking to myself, you know, 40 years ago, this kind of person would have been an anti-Semite. There’s a real fixation on the state of Israel. That was why Trump moved the embassy to Jerusalem, and it was a really big deal for these guys. Trump even gave a speech to some sort of Israeli American business group or something like that. And he said, Yeah, the Evangelicals liked that even more than you guys did when I moved the embassy. So there really is that focus on End Times. That, and speaking to people’s material conditions. That’s given it a rapid rise in the last 40 years. There’s a focus on health and wealth and things that really matter to people. The End Times apocalypticism is still definitely there. Most importantly, there have been real theological shifts, and now that they believe that they’ve got to create the conditions on Earth for Jesus to return. And obviously, that’s where it becomes really politically charged with Christian dominionism. So it can be quite motivating, I suppose, to some people in the short term.

Robinson

What does pre-millennial mean?

Hardy

The millennials said that God would come back so Jesus would return to Earth first. And then you’d have the tribulations and the rapture and all of that kind of stuff. So then he would rule for a thousand years. Post-millennialists say that we’ve got to create the conditions and then he comes back—I’m not a theological scholar or anything like that, so there might be some things I’ve not explained very well. But it doesn’t sound all that profound. But the political consequences are pretty clear.

Robinson

Right. You’ve talked to a lot of people who have converted and have undergone what they see as deeply profound, transformative experiences. And what is common among those people? What do you see as drawing people into this? What is the story they tell about why this faith lured them in?

Hardy

It’s really interesting. The first thing to understand is that conversion is very meaningful to people. Part of the success and the fervor of Pentecostalism has been about being born again; it’s that real, clear demarcation of your life before and after. And a lot of people do tend to have this moment when they’re at their lowest in life. In Latin America, it’s often the only form of addiction treatment. So men in particular may struggle with alcohol and drugs and gambling and things. Oftentimes, it’s only a Pentecostal church that will provide any sort of base level of support. And that’s where these people go. And if they’re able to kick the habit, they have a very clear demarcation of before and after. And they get really good at converting other people by telling their story. If there was a really clear driver, it’s health and wealth. Health care by way of miracles. Often, Pentecostal churches are almost parasitic institutions in a lot of places in the world. Tithing is a form of taxation. Parts of South Africa and Nigeria and Latin America that I’ve been to will have a small medical clinic. There’s not a lot of state health care or anything like that. So, this might be the only place you can get that bit of health care or child care, or at least you’re able to put your child in an after-school choir or something like that, and they’re not running around on the street.

For example, in South Africa, there’s 75% youth unemployment. So these are really important things that the church is offering that the state simply isn’t. And then wealth. The prosperity gospel is a pretty Pentecostal doctrine. And obviously, it’s pretty awful when you see some of these guys that have their private jets and Rolls-Royce in some of the most impoverished parts of the world. But there’s a lot of evidence coming out of Brazil particularly that the prosperity gospel works. People tend to see an uptick in their circumstances when they start going to Pentecostal church. Part of my theory on this is that you’re buying into an accountability network. People are putting something on the line. When you get into this church, you’re hoping to see something in return. We also live in a society where we equate value in something with paying for it. So it’s not so unusual.

You can understand the logic. You might be giving to this preacher that really inspires you—your Tony Robbins seminar, or whatever. It’s quite a similar principle. Pentecostalism is particularly thriving in really big cities like São Paulo, Moscow, Los Angeles, Sydney, London—it tends to be people who are migrants or minorities or people that might have moved from a small town. And as São Paulo was growing in Brazil, people were moving from all over the country, from small villages to São Paulo to work in big factories. And those are pretty tough life circumstances. And maybe going to a church is a way of replicating some sense of community and culture. In London the churches are really big among the West African and Caribbean diasporas. You can be a Nigerian kid in London in this huge cosmopolitan city, but also retain some of your Nigerian or Romani background. Gypsies and Romani and traveler people are converting really rapidly in Europe. And it’s often quite tied up with identity and the way that you can almost be yourself privately on Sunday, or whenever you go to church. And then you can be another face in this big, crazy city for the rest of the week.

Robinson

I don’t mean to sound Marxist, but it sounds as if part of the explanation from your observations seems to be related to material conditions. It almost seems linked in some way to what is known as neoliberalism. You point out the lack of state services for people, that they’re moving into places where they are economically deprived, and the church is giving them things that they have been deprived of. And that seems pretty straightforward. So what the person experiences as a conversion of ideas—a shift into believing in something—is built on this foundation of the conditions in which they’re living.

Hardy

There’s a thing in Pentecostalism that Pentecostals preach for Monday, not for Sunday. So it really is all about just trying to exist in the modern world. Part of the appeal of modern Pentecostalism through things like Hillsong music is that it says, You can be a Christian in the modern world and you don’t have to go without things. Pentecostalism is, I think, part of a shift to post-millennialism. But it’s really good at uplifting and making people feel good. A Pentecostal sermon is like a self-help talk a lot of the time. It’s very modern. I met a really lovely Pentecostal preacher in Mozambique who gave this really profound sermon about Facebook and how everyone’s coming to him. And they’re upset because they’re seeing that other people’s lives seem to look better on Facebook. He talked about how he works through that with people and explains that everyone’s only putting their best face forward on Facebook. They’re not showing the difficult parts of their lives. That’s obviously sort of a riff on not coveting your neighbors, the Ten Commandments. These things really seem to matter to people.

In particular, in post-apartheid South Africa, I think there’s a really interesting lesson in Pentecostalism. People are flocking to the churches because they’ve been so let down since ‘94. These were young people who were promised a lot. All the bad stuff was meant to be over, and it’s just been more corruption. There’s still discrimination there in many forms, and church is a place where you can go and be uplifted. South Africa itself has failed, but there also is a real sense that things like the IMF and the European way—they were promised, if they neoliberalized, that everything would be fine—just haven’t worked. So the Pentecostal preachers are quite big and really extreme in South Africa. One is called the “church of horror.” Sometimes they’ll eat snakes and things like that. But they’re millennial guys, and they’re anti-everything that’s come before because they’ve been let down by that. Again, part of the Pentecostal appeal is that it’s not coming down from Rome. It’s bubbling up from within the community. So it really speaks to anger and resentment, but also hope and opportunity and possibility, and maybe branching out and doing things your own way because everything else you’ve been promised sucks.

Robinson

Yeah. Some of the things that you write about are quite alarming. The reactionary politics is a serious concern. But I’m sure you also saw things in your travels and observations that were quite moving. When did you say to yourself, Oh, people seem to really be getting something good out of a community that they didn’t have before?

Hardy

One of the groups that I’ve found most fascinating is the North Korean defectors to the south. Pentecostals and Christians mostly run the underground railroads. True believers are the ones that tend to put things on the line. People sometimes convert because they have to. If someone’s going to risk their life in China having you in their house, they might insist on your reading the Bible. It’s a really profound moment when you’re leaving everything behind. And so a lot of people do tend to convert, but then they get to Seoul, and they just can’t cope. It’s this huge city. It’s alienating. And once again, the only real places that offer them stuff are the churches. There’s a thing that North Korean defectors talk about. It’s called showing your face. It means having to go around to all the different churches and get a bit of a stipend. Someone will bring some used clothes for you, and there might be a dentist who goes to your church and gives you some free services. But, again, it’s often the only game in town for a lot of people. Even in parts of America, these are often the only philanthropic and charitable places that are actually providing these services.

Robinson

You’ve mentioned Hillsong a couple of times. Explain to unfamiliar readers and listeners what that is. It comes from your own home country of Australia, as I understand it. That’s not a place I would necessarily associate with having created a successful—would you call it a branch or a sect of Pentecostalism?

Hardy

It comes out of my hometown of Sydney, from the early ‘80s. And it’s quite bizarre. Australia is still, to this day, very hostile to evangelicals. It’s not a common faith in Australia, where we tend to be of people who are Christian—it would be 50/50 Catholic and Church of England Anglicanism. Evangelicals are still a pretty small minority. So it really came about with what we call the third wave of Pentecostalism. That’s that early ‘80s and ‘90s globalization, end of history, whatever you want to call it. But what Hillsong really popularized was the music. They had an in-house band that just did really modern music that was good and uplifting, which sounds like something that could sneak in on the end of your Spotify playlist. You can have the good stuff of this world. To be a Christian, you don’t have to be apart from everything. Some Hillsong guys are really good at social media, and it’s really spreading. So now they’re a real leading light in how to commercialize your church. A very similar church in the U.S. is Bethel. They’re a bit more fire and brimstone, but they actually opened their books, kind of, at one point a few years ago, and 19% of their revenue comes from tithing. Eighty-one percent comes from music sales, merchandise, and their college, and I’d say Hillsong would be pretty similar. Hillsong became known as Justin Bieber’s Church, the celebrity church. Carl Lentz was the preacher who had a real fall from grace—I think in 2020—for having affairs and whatnot. Many celebrities were turning up to the LA churches: Kardashians, Jenners, and things like that. The church became really well known for just that. They pioneered that uplifting style that you can feel good about. People don’t want to feel like shit. People are working two jobs and studying and all that kind of stuff. You can go to church and be uplifted, feel really inspired for your week, and then get on with your day. It’s not like Reverend Lovejoy in The Simpsons who’s preaching to you while you’re falling asleep and telling you about damnation. It’s really all about feeling good and uplifted and inspired and being around young people.

Robinson

The Church of England is not known for inspiring people. These days, you almost get the sense that the Church of England vicars barely believe the faith themselves a lot of the time. I consider myself a leftist. I consider myself an enemy of reactionary, anti-LGBT, anti-trans politics and Christian dominionism, which terrifies me a little bit. A lot of this seems relatively benign. And a lot of it doesn’t. When people are going in, they’re having a good time and they feel full of the Holy Spirit. If I think it’s bunk, it’s because I’m a secular, atheist/agnostic. But good for them. I’m glad they’re being fulfilled by it. But there are other signs, like the links to Trump and Bolsonaro, that are really quite concerning. So what is the lesson for those of us on the left? One of the things you point out is that people have material needs. They have spiritual needs. Those needs have to be fulfilled somehow, and if they’re not being fulfilled, then there can be charlatans and pretty scary ideologies that step in to fill those needs. And if society can’t offer people something to fill the belly and fill the soul, we’re not going to succeed, and clearly secular liberalism has not given many people what they need.

Hardy

Western secular types, agnostic types—I fall into a similar category as you—we often forget that many people in the world have a really spiritual conception of the world. Nourishment is important. I’m not a religious scholar. And I’m not a person of faith myself. But the book focuses on those material needs and what the faith gives people. There’s a failure of so much of secular liberal democracy—which has certainly done a fair bit of good—but in so many parts of the world, it isn’t working. And so many times it’s only the churches that are there to pick up the pieces for people. Who else is providing this stuff? I’ve done the odd bit of volunteer work in a homeless shelter, but not with any great commitment or regularity. True believers are the people that tend to do this stuff, and that’s why they can be pretty troubling politically. Sometimes they will force their ideas onto other people. But I just don’t know who else is doing this stuff. Maybe it’s just worth thinking about instead of worrying so much about what other people’s faith is saying. It’s maybe saying, Well, how can we do things a bit better?

Robinson

You must have had times where you wished you could be filled with the Holy Spirit.

Hardy

Sometimes I did. In South Africa when I saw a sangoma, or a faith healer. And I did have those moments where I envied their faith and their certainty and their community and what it provides, for sure.

Robinson

Your book is totally fascinating. You’ve reported from many countries and many states, and you tell many really interesting stories. You excavate the history, and you show why it matters for our world. Thank you so much for talking to me.

Hardy

Thank you for having me.