How Creative Writing Programs De-Politicized Fiction

In the shadow of the Cold War, the rise of creative writing programs and ‘show don’t tell’ philosophy drained fiction of its political bite.

If I were to devise a scene that showed the starting point for modern American literature, I would begin in a creative writing classroom in the 1950s. A group of young people has been corralled into a seminar room where an instructor, in horn rim glasses and herringbone blazer, is torturing the adverbs out of first drafts. The writing program has been created in the hope that under no circumstances should these students engage in ideology or broad societal critique in their work. Instead, the individual was to be the ceiling and the floor of literature.

Eric Bennett, an English professor and graduate of the MFA program at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, in 2015 published Workshops of Empire, a book about how creative writing emerged as a discipline used to promote capitalist values during the Cold War. In America’s creative writing programs, Bennett writes, “the artistic mind found protection from the dangerous influence of Communism.” Through university programs, “the aspiring writer embraced the dream of a nuclear family and a steady job at the same time he was learning the techniques of the modernist form.” Writers, like everyone else, had to get dressed in the morning and head to the office. It was the Cold War. Political quietism and introspection were in. Communism and broad societal critique were out. Literary fashion followed the conservative Flannery O’Connor, a writer who, however brilliant, dealt exclusively in the scouring of atomized souls. Left-leaning authors who wrote with a wide scope about communities and politics—writers like John Dos Passos, Langston Hughes, and John Steinbeck—were passé.

Following the passage of the GI Bill of 1944, which funded higher education for armed service members, creative writing programs began popping up across the nation after the war. They were mainly modeled on the Iowa Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa, established in 1936. Many were founded by graduates of that program. The design of these programs has essentially remained the same to this day. Up-and-coming writers are placed in micro-communities of competitive peers in isolated academic environments. They attend workshops, led by professional writers, in which new pieces of student writing are critiqued each week. Following these workshops, students are supposed to return to their work with a broadened perspective, enlightened by the opinions of their peers and professor.

Sandra Cisneros, author of the novel The House on Mango Street, earned an MFA at Iowa in 1978. Writing about the program in her 2015 memoir A House of My Own: Stories from My Life, she wrote, “How can art make a difference in the world? This was never asked at Iowa.” “In grad school, I’d never been trained to think of poems or stories as something that could change anyone’s life but the writer’s. I’d been trained to think about where a line ended or how best to work a metaphor. It was always the ‘how’ and not the ‘what’ we talked about in class.”

This emphasis on form over content was still common when I became a creative writing student thirty years later. As a student in the late aughts, I wrote an (overambitious) story in which a male sex worker, a drag queen, and a club bouncer discuss theology with a Catholic monk in a gay bar in Manhattan. When the story was workshopped, the professor went around the seminar table and asked everyone to draw a diagram of the bar. My classmates spent an hour analyzing this space: where the tables, dance floor, and exit were located in my fictional bar. Not one comment did I receive about the actual content of the story. It was all “how” and not “what.” The subject matter, the “what,” was treated as ornamental and didn’t enter into the analysis. Approaching the form of writing in this way can be useful: you clear away the facade and work on the foundation. Here, however, the foundation of my story was treated as if it was devoid of content. What mattered to my teacher was where the tables and chairs were. The moral dimensions of my story and its topic of sex work were pushed completely aside.

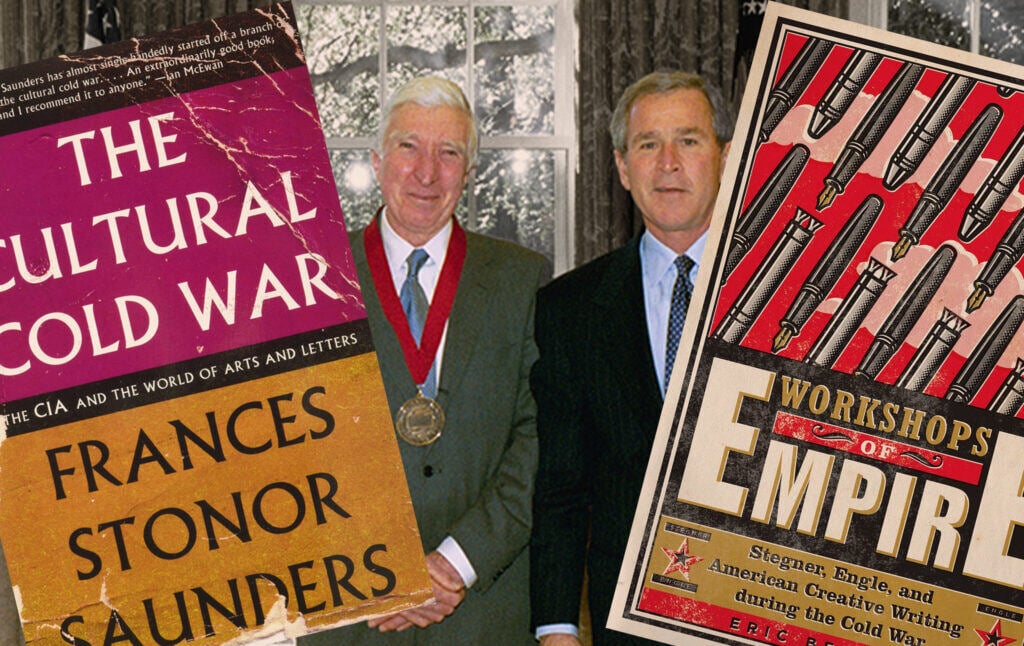

While divorcing the craft of writing from the content of writing is not explicitly anticommunist or pro-capitalist, it is notable that teaching writing in this way grew to popularity during the Cold War and was popularized by vocal anticommunists. Paul Engle, the Iowa Writers’ Workshop director from 1941 to 1964, fundraised for the program using explicitly anticommunist rhetoric: he communicated with private and public donors that Iowa was in the business of bringing writers together in one place to train them to compete against their ideologically-driven counterparts in the Soviet Union. In his essay “How Iowa Flattened Literature,” Eric Bennett writes that Engle was explicit in his political motivations in his fundraising for the program. “Iowa prospered on donations from conservative businessmen persuaded by Engle that the program fortified democratic values at home and abroad: It fought Communism,” Bennett writes. Through these efforts, Engle brought in money from the Rockefeller Foundation, The State Department, and CIA front groups the Farfield Foundation and the Asia Foundation.

These organizations were giving money to Iowa at the same time that the CIA was funding literary magazines worldwide through the Congress for Cultural Freedom. In the U.S., they supported The Kenyon Review, to this day one of the most prestigious literary reviews in the nation. The review was a proponent of The New Criticism, a form of literary criticism in which the critic avoids making reference to the historical, political, or personal context in which a work of literature was written. In The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters, Frances Stonor Saunders describes how the review’s founder, John Crowe Ransom, had ties to the CIA. He received funding from the CIA through the Congress for Cultural Freedom, and had some of his students recruited to the CIA. The Paris Review, another mainstream literary light influenced by the apolitical New Critics, began as a front group for the CIA. Its founder, Peter Mathiessen, was himself a CIA agent.

We know that the CIA was interested in art and literature during the Cold War. Exactly what impact this interest had on literature itself is hard to quantify. However, looking at the literature of the period through a wide angle lens, you can see a shift away from political literature or literature of broad cultural scope. When I was first studying literature in college, I started putting a dividing line between literary novels written before and after World War II. It seemed like the books from the before times were good at doing lots of things. They could world build and philosophize. They could be love story, adventure novel, and satire all in one. Books written after the war, however, could only do one thing at a time. Mostly that one thing was soul-searching or introspection. Serious postwar fiction, whether it was what I was being fed in school or read in the pages of The New Yorker, was about sad white people with relationship problems.

Cold War writers like John Updike, J.D. Salinger, Flannery O’Connor, and John Cheever—soul-scouring chroniclers of the small—were beloved of my baby boomer teachers in high school and college. When I was being educated, I was assigned John Updike’s often anthologized “A&P,” first published in 1961, in four separate academic classes. This is a story about a supermarket cashier who gets turned on by a teenage girl in a bathing suit. The narrator watches the girl and her friends wander through an A&P in bathing suits. The writing is gorgeous, and very much of its time: the girl’s bare chest in a strapless bathing suit is “like a dented sheet of metal tilted in the light.” At the end of the story, the store manager tells the girls to put some clothes on. The cashier responds by quitting his job. His dramatic gesture isn’t perceived by the girls, and the cashier wanders away, sad and jobless. It ends, “My stomach kind of fell as I felt how hard the world was going to be to me hereafter.” That’s the entire story.

The writing is well crafted. It’s not a bad story. But not only does it foreground the male gaze and very little else, it also reads as though cut off from time and space and other people. The narrator’s coworker is “married, with two babies chalked up on his fuselage already.” His coworker cannot do anything so effeminate as to father babies, so he instead guns them down over Normandy. Slave to his hormones, the narrator doesn’t make choices. He reacts. One minute he is watching the girl blush, and the next he is throwing in his bowtie and walking out the door. The store, the character, the scenario, are all vehicles for describing a girl with “a good tan and a sweet broad soft-looking can with those two crescents of white just under it, where the sun never seems to hit.” Lean, sculpted sentences all. But in service of what, exactly?

I don’t believe that fiction must have deep societal meaning. Of course, stories can exist for themselves. Writing about his literary vocation towards the end of his life, Updike wrote “my only duty was to describe reality as it had come to me – to give the mundane its beautiful due.” I find Updike’s vision very noble. What is unique in Updike’s writing, however, and in much writing from the postwar period, is how little it does beyond this beautification of the mundane. Whereas a more politically-oriented writer might take the scenario in “A&P” and use it as a vehicle for the class inequalities on display—the poor cashier, his overbearing boss, the privileged teen girl who doesn’t know he exists—and ask questions of the reader or draw moral assessments, Updike’s story stands for itself. The story is experienced almost in real time, like a film. Updike keeps our attention on the object of consumption: the bare shoulders of the teenage girl. Given a different ending, I can imagine the story as a beer commercial (toss the bowtie, kiss the girl, drink Miller High Life). There are moral or spiritual or societal dimensions that could be dealt with in “A&P,” but the text is stripped clean of much beyond the beautifully rendered surface.

Midcentury writing like Updike’s would be a historical footnote had its tenets not been ingrained in writing programs nationwide. Bennett, in Workshops of Empire, describes the teaching philosophy of creative writing programs at mid-century as supporting “Sensations, not doctrines; experiences, not dogmas; memories, not philosophies.” The primacy of this type of writing, buoyed up by MFA programs, publishing houses, and (sometimes CIA-funded) magazines, was long lasting. If you have taken a writing class in the United States in the last seventy years, you have probably received lessons that have been handed down from this period: from the New Critics and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. You may, for instance, have been told that writing should “show and not tell.” In some ways, this advice is sound. To show (sensations, experiences, and memories) and not tell (doctrines, dogmas, and philosophies) in narrative fiction is a good idea. While people love to enthuse over what interests them, what readers need to know to understand what is happening usually needs to take precedence over a writer’s passions. In the decade in which I taught writing I had to steer plenty of students away from “info-dumping,” from giving a lecture about family genealogies, magical powers, or how physics works in a fantasy universe—and to structure stories around action. It’s a way to get a student to stop thinking of themselves and to start thinking about their reader.

The problem with “show don’t tell” is that applied to actual literature it becomes over-simplistic. Literature historically is full of dogmas, doctrines, and philosophies. It’s full of writers telling you things. Thomas Mann philosophizes at great length; Leo Tolstoy fills chapter after chapter with moralizing dogma; and certainly no one ever applied to Herman Melville the rule about showing and not telling regarding his whale taxonomy lists in Moby Dick.

Even on the most practical level of information delivery, showing and not telling isn’t always the best option. Consider the following passage from Pride and Prejudice, published in 1813, in which Jane Austen introduces the novel’s famous love interest:

Mr. Darcy soon drew the attention of the room by his fine, tall person, handsome features, noble mien, and the report which was in general circulation within five minutes after his entrance, of his having ten thousand a year. The gentlemen pronounced him to be a fine figure of a man, the ladies declared he was much handsomer than Mr. Bingley, and he was looked at with great admiration for about half the evening, till his manners gave a disgust which turned the tide of his popularity; for he was discovered to be proud, to be above his company, and above being pleased; and not all his large estate in Derbyshire could then save him from having a most forbidding, disagreeable countenance, and being unworthy to be compared with his friend.

Here telling instead of showing—giving the action in exposition, as background information— allows for a multivalenced perspective: we see how everyone at the party came to perceive Mr. Darcy. He is handsome, rich, and kind of an asshole. Darcy is filleted by the protagonist’s community before the characters meet. He doesn’t arise out of nowhere, a singular highlight upon which her imagination can run wild with metaphors. Instead of showing him walking into a room, Austen tells us what everyone in the room thinks of him after an evening of conversation. Just as we view people in real life, his character is a composite of many perceptions at the same time.

Shown detail, which can be affecting and beautiful, has an entirely different impact and narrative purpose. In Updike’s “A&P,” the “shown” object of affection is introduced as follows:

She didn’t look around, not this queen, she just walked straight on slowly, on these long white primadonna legs. She came down a little hard on her heels, as if she didn’t walk in bare feet that much, putting down her heels and then letting the weight move along to her toes as if she was testing the floor with every step, putting a little extra action into it. You never know for sure how girls’ minds work (do you really think it’s a mind in there or just a little buzz like a bee in a glass jar?) but you got the idea she had talked the other two into coming here with her, and now she was showing them how to do it, walk slow and hold yourself straight.

Written in first person, from the point of view of Updike’s horny teen protagonist, we linger for sentences on the girl’s footsteps. In Austen, through the told description, we become a part of the hive digestion of Darcy. In Updike, outside perspectives are dismissed (A&P shoppers are “houseslaves in pin curlers”) and the narrator, the independent soul reveling in the girl’s freedom and beauty, is—like you, the reader at home—different and special. Only he is consuming her in the right way, even if it gets him into trouble. On the level of language economy, Updike spends several sentences of a very short story writing about a girl’s footsteps. In Austen’s novel, in exactly the same number of words, a major character is introduced and physically and morally dissected by an entire community.

Austen is telling. Updike is showing. The deft handling of these tools, knowing when to use one and when the other, is the art of fiction writing. Updike also does his share of ‘telling’ in “A&P,” although the writing is stream-of-consciousness and the reading experience is more like showing than telling. Yet, how to ‘tell,’ how to give concise and witty information in exposition (à la Austen), is rarely taught in a classroom. How to ‘show,’ meanwhile, how to describe a girl walking barefoot across a supermarket, is the bread and butter of every fiction workshop in the land.

Writing teachers like to say that great writers can break the rules because they know the rules to begin with. But this idea implies that the rules have always been the same and the needs of readers have always been static. The notion that “giving the mundane its beautiful due,” describing a barefoot girl walking across supermarket tile, is the purpose of fiction, may have come as news to a writer like Jane Austen. She was as much moral philosopher and social satirist as she was crafter of fine sentences about the mundane. These static mid-century rules imply a stultifying sameness throughout the whole of world literature. Their continued adherence in academia implies that we are stuck. Just as it is hard to imagine a world after capitalism, it is hard for American fiction writers to imagine a literature after Updike and Salinger. The midcentury poetics that were institutionalized during the Cold War, at least partially for political reasons, have, I believe, brought literary fiction to a dead end.

Here in the third decade of the 21st century, according to NEA statistics, readers of literature have become steadily fewer and fewer in the last forty years. Writers’ incomes have also decreased. The transforming market, new technology, and shorter attention spans are all being blamed for the shrinking of fiction’s readership. I would further add that trends in fiction writing itself, in which stories are built upon narrower and narrower subjectivities until the only readership left is that of the writer alone, is also to blame for this exodus. These combined factors have driven literature towards contemporary obsolescence.

In the last forty years, in the same time that readership has declined, creative writing programs have blossomed. There were 52 MFA programs in 1975, whereas as of 2016 there were 350. The creative writing business makes over $200 million a year in revenue. There are more MFAs and other businesses that grew out of the Iowa workshop model, and more people willing to spend real money to go to MFA programs and attend conferences and workshops where authors, agents, and editors dole out advice on how to get that book deal. The literary world once looked to readers of (relatively inexpensive) books for its sustenance. Now, it relies upon costly creative writing education products, and hopeful writer-consumers willing to buy them.

Literature, part of our human birthright, has, like our food and water supply, our systems of care and education, and so many other things, been ransacked and misused by capitalism. Retaking that birthright, I believe, is a small part of the struggle to build a better world. I believe that writers have a duty to use their talents, their ability to show and tell—“to give the mundane its beautiful due” and to channel broad and diverse perspectives in narrative form—to help build that better world. Not only can writers envision new worlds, they can also build schools, publishing houses, and publications that work against the capitalist ethics enthroned in the American literary establishment. They can widely broadcast stories about mass climate action, the labor movement, and left-wing solidarity. Where literary institutions during the Cold War popularized a fiction of atomized soul scouring—a flattened formalism that is still being taught in academia—new institutions can help conceptualize a post-capitalist world. Writers and artists, taking their cues from creative writing programs themselves, can build institutions. After all, institutions have created the stranglehold of liberal capitalism on the arts. Perhaps institutions, built and sustained by the left, have the chance to break that stranglehold.