A Brief History of the Bourgeois Safari

Safari is a popular form of ecotourism often billed as a benefit for conservation. But this colonial practice cannot make up for centuries of exploitation of Africa’s people, wildlife, and lands.

“African development is possible only on the basis of a radical break with the international capitalist system, which has been the principal agency of underdevelopment of Africa over the last five centuries.”

Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, 1972

“The only positive development in colonialism was when it ended.”

Walter Rodney

“Natives live in harmony with nature but outsiders destroy it.”

Ernest Hemingway, Green Hills of Africa, 1935

In April 1991, a few years before he would be elected President of South Africa in the country’s first election based on universal suffrage, Nelson Mandela appeared on the cover of the newspaper Weekly Mail, kneeling in grass at the Mthethomusha Game Reserve. In one hand, he held a hunting rifle; in the other, the horn of a blesbok, a species of antelope that he had killed moments before while on safari. The headline declared, “Mandela goes Green. A hunting trip converts ANC [African National Congress] leader to conservation.” Mandela had gone on a two-week safari to hunt and learn about ecology—“at a time when most blacks could still not hunt legally, let alone own guns” and when “conservation [had been] long identified with the marginalization of blacks in South Africa,” writes Jacob S.T. Dlamini, author of Safari Nation: A Social History of the Kruger National Park, the cover of which features the newspaper image of Mandela. Mandela also went to visit Kruger National Park, one of the most popular national parks in the world. His trip would mark the beginning of the ANC’s commitment to conservation in postapartheid South Africa, as well as to reforming the national parks system into one accessible for all people and one which considered the needs of locals. Kruger in particular had represented, from colonial times, the government’s efforts to “promote a ‘national feeling’ among whites” and to “promote a sense of nationhood built on the exclusion of indigenous peoples,” writes Dlamini. (Dlamini notes that there was a similar attitude in the U.S. around the creation of Yellowstone National Park in 1872; South African parks documents at the time of the creation of Kruger show numerous references to Yellowstone. Indigenous Americans were forcibly relocated for the creation of that park. Jessica Hernández, cited later in this article, notes that the 1906 Antiquities Act, which gave the president the authority to “protect prehistoric Native American ruins and artifacts,” did not do anything to protect Indigenous people, who were denied access to the park around that time.)

The Mandela article highlights some familiar themes in modern conservation. The land for the reserve was said to have been “donated” by the leader of the “local Mpakeni clan,” a more “sensitive approach” than that which usually happened when parks and reserves (including Kruger National Park) had been created in Africa, whether under colonial or postcolonial governments: displacement of area natives. Mandela said in the article that conservation ought to aid local development and be done in consideration of the needs of local people. The tourist proceeds from this particular reserve, including those from hunting, were split more or less between the parks authority and the Mpakeni clan, which used the money for “schools, clinics, and other social services.” The reserve only allowed the hunting of “overpopulated species,” which was noted to be beneficial to the ecosystem as well as a deterrent to poaching. “As a result local people develop a deep respect for animals and other species to be protected.”

Put another way, the article promoted the following ideas: the idea of enclosing land to make parks or reserves, often separating land and wildlife from people; the idea of partnering with local people on conservation projects, as opposed to displacing them or evicting them outright; the idea that conservation projects, especially safari hunting tourism, could be used to promote human development (and/or poverty alleviation) along with wildlife conservation; the idea that killing animals via hunting is preferable to killing them via poaching; and also an assumption that the local people need to be taught “respect” for nature. For the latter, depending on the historical time frame under consideration, local people may have been living on the land in question for decades or longer, in which case their connection to the landscape (and their knowledge) would be much deeper than that of outside conservationists. In other cases, if people in a natural area migrated from urban areas and did not know about or practice the traditional lifestyles of the area, they may not know as much about the natural environment (a key legacy of colonial “education” was that Africans were left largely uneducated about their own culture, history, and landscape and educated instead about European culture, history, and landscape). If one takes the idea of teaching local people how to respect nature to its logical conclusion, we get to an assumption that tends to underlie conservation projects on the continent. That assumption, as Benjamin Gardner writes in Selling the Serengeti: The Cultural Politics of Safari Tourism, is that “African nature is too valuable to be managed by Africans.”

Dlamini notes that “Mandela’s hunt actually took place … at the Songimvelo Game Reserve.” In any case, both that reserve and the Mthethomusha Reserve were under the domain of the KaNgwane Parks Board. KaNgwane was a Swazi-speaking non independent Bantustan. Bantustans, also called homelands, were areas to where native black people were forcibly relocated under apartheid. Dlamini said in an online discussion that the purpose of these homelands was to “dilute and neutralize” black claims to political power. Even though the scenario in the Mandela article appears to involve Africans managing an African landscape, it will become more apparent in other scenarios who the outside Westerners or conservationists are and why some African groups choose to cooperate with conservation projects, and their reasons for doing so. It should also be noted that the National Parks Board of South Africa was a thoroughly white institution, seating its first black member in 1991. KaNgwane would ultimately be reincorporated into South Africa in 1994 at the end of apartheid.

Modern conservation as applied to African wildlife and landscape is rooted in Western colonial attitudes and practices that have, in the past and modern times, been carried out to the detriment of Indigenous people and land, causing disruptions to communities that can lead to “famine, disease, and death.” Indigenous scientist Jessica Hernández, author of Fresh Banana Leaves: Healing Indigenous Landscapes Through Indigenous Science, writes about Western conservation from the perspective of an Indigenous person of the Americas. In the book, she explains:

Conservation is a Western construct that was created as a result of settlers overexploiting Indigenous lands, natural resources, and depleting entire ecosystems. According to National Geographic, conservation is defined as “the care and protection of … resources so that they can persist for future generations. It includes maintaining diversity of species, genes, and ecosystems, as well as functions of the environment, such as nutrient cycling.“

Furthermore, Indigenous people were already “conserving” their land prior to colonization. And as Hernández explains: “Conservation did not exist precolonization because Indigenous peoples viewed land as communal, meaning no one person owned it.” Western and capitalist notions of private ownership were exported by Europeans onto the African continent as well.

Economic anthropologist Jason Hickel (who is from Eswatini) has written about the roots of European enclosure, or the privatization of land in order to create resource scarcity. This was employed by Europeans during colonization:

The same process unfolded around the world during European colonization. In South Africa, colonizers faced what they called “The Labour Question”: How do we get Africans to work in our mines and on our plantations for paltry wages? At the time, Africans were quite content with their subsistence lifestyles, where they had all the land and the water and the livestock they needed to thrive, and showed no inclination to do back-breaking work in European mines. The solution? Force them off their land, or make them pay taxes in European currency, which can only be acquired in exchange for labour. And if they don’t pay, punish them.

In his 1972 book How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, the Guyanese Marxist historian Walter Rodney argued that African nations, having been formally colonized by Europe for just over 70 years, had ended up underdeveloped (socially, politically, culturally, and economically) to the degree that Europe had become developed in that same time period. Colonization was a large part of the reason that, upon independence, African nations emerged stunted. Rodney wrote that, prior to the arrival of Europeans in the 15th century, the African continent was unevenly developed. Some societies existed closer to a state of feudalism, as Europe had been on the eve of its transition to capitalism. But many African societies resided in a state of communalism, which, unlike feudalism, was non exploitative and was governed by customary land rights. This meant that the land was communally owned on the basis of ethnic or tribal ties and history of occupancy to the land. “Customary and collective land rights … were dismissed under colonial rule,” writes Gardner. Land was thus used to serve colonial economic interests, whether for natural resource extraction (such as mining), to build transit, or to build reserves, especially for big game hunting, a favorite sport of gentlemanly European elites that peaked in British East Africa (which approximates modern-day Kenya) in the early 20th century prior to the outbreak of World War I.

Furthermore, the idea of separating people from land and wildlife forms an important underlying assumption in modern Western conservation. This is the idea of “fortress” conservation, an idea

based on the belief that biodiversity protection is best achieved by creating protected areas where ecosystems can function in isolation from human disturbance. Fortress, or protectionist, conservation assumes that local people use natural resources in irrational and destructive ways, and as a result cause biodiversity loss and environmental degradation. Protected areas following the fortress model can be characterized by three principles: local people dependent on the natural resource base are excluded; enforcement is implemented by park rangers patrolling the boundaries, using a ‘fines and fences’ approach to ensure compliance; and only tourism, safari hunting, and scientific research are considered as appropriate uses within protected areas. Because local people are labeled as criminals, poachers, and squatters on lands they have occupied for decades or centuries, they tend to be antagonistic toward fortress-style conservation initiatives and less likely to support the conservation goals.

Separating people and land under the “fortress” conservation model “denies the possibility of people sharing the land with wildlife as a viable practice,” writes Gardner. This is a problem for Indigenous people all over the world whose livelihoods depend on their access to and relationship to the land and its flora and fauna. The roots of this modern trend in land enclosure can be seen in the colonial practices around hunting. Colonial administrators needed tracts of land which could ensure that elites, mostly from Europe, had undisturbed access to ample big game. In fact, the Europeans were so fond of hunting that they “shot out” the big game and had to impose regulations. In one review of books in the white-man-goes-trophy-hunting genre, there’s a quote from John Tinney McCutcheon’s 1910 memoir In Africa: Hunting Adventures in the Big Game Country: “The Belgians place no limit upon the number of elephants one may shoot. … In British territory, however, sportsmen are limited to only two elephants a year to those holding licenses to shoot.”

The Germans gained control of Tanganyika (which, along with Zanzibar, became modern day Tanzania) in 1885, and they preferred ivory. Writes Gardner, “Soon after colonizing the country the Germans created regulations to protect the remaining wildlife and regulate its use for hunting. Colonial laws effectively banned customary hunting,” although locals could “apply for a license to hunt” or else had “severely limited” access to what eventually became formal game reserves. Thus, wildlife went from being a communal natural resource to being mostly for European use and profit. The British would gain control of Tanganyika after World War I, at which point they enacted game ordinances which kept locals out. Gardner writes that in Tanzania, whether under colonial or postcolonial governments, “controlling wildlife” would remain “central to accumulating state wealth and maintaining authority.” In neighboring East Africa (Kenya), by the 1930s, the British realized they would need to conserve wildlife if hunting was to remain a viable industry; that was thus one impetus for the creation of national parks around that time.

In Selling the Serengeti, Gardner gets to know Maasai activist and former Tanzanian MP (Member of Parliament) Lazaro Parkipuny, who had this to say about the settlers’ appetite for the hunt:

Indeed the excitement of the whites, colonial civil servants, missionaries and settlers alike was not climaxed in watching, photographing and describing the scenery and wealth of wildlife they found here. Their pleasure was only recorded and hearts fulfilled at sights such as the heaviest ivory from the biggest horn of a ferocious rhino that took a bullet in his brain, the display of the biggest horns of a sable antelope shot; the distance at which an eland was killed with a small caliber rifle, etc. … The main attraction of the Serengeti to Europeans at the time, up until the 1930s, was shooting lions [that were] helpless in the extended [plains].1

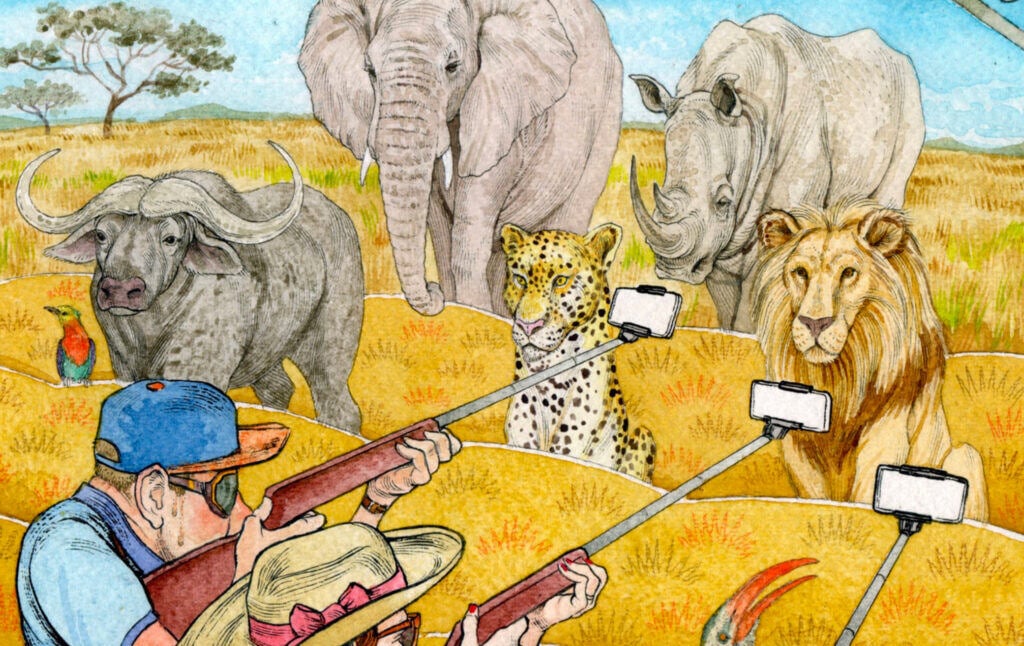

The colonial attitudes and practices that lie at the origin of Western conservation show up conspicuously in the modern safari, whether for sightseeing, photography, or trophy hunting. Essentially, safaris glorify the European colonialism from which they originate. Note the following aspects of safaris:

- The iconic Hemingway-style tents and “colonial style safaris. ”

- The practice of having “sundowners,” also referred to as “happy hour in the bush.” (Referring to the G&T or gin and tonic, the author writes of a sundowner: “It’s quite tasty. And it’s historical. Yes. Historical.” By this she means that the quinine in the tonic water had antimalarial properties that came in handy as the Brits “trundled on into more and more malaria-infested lands” in Africa.)

- The focus on the Big 5, a term referring to big game species that were considered the most difficult to hunt by foot: the African buffalo, African bush elephant, leopard, black rhinoceros, and lion.

- The practice of posing with one’s kill. (See photos of Theodore Roosevelt’s safari, to be discussed, here).

Safaris purchased today descend conceptually from safaris that originated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as European powers were “carving up” Africa into various regions under their rule and bringing in white settlers. “Safari emerged as a form of tourism at the precise moment that imperial expansion in Africa was reaching its peak,” writes Trevor Mark Simmons in Selling the African Wilds: A History of the Safari Tourism Industry in East Africa 1900-1939, from which most of the details in this sketch of the colonial origins of safari have been drawn. As Simmons quotes Elspeth Huxley’s 1948 Settlers of Kenya, he notes that Sir Charles Eliot, the Governor of the British East Africa Protectorate, said in 1903 that “the main object of our policy and legislation must be to found a white colony.” Indeed, these former “white colonies” are now some of the top tourist destinations for safari: Kenya, Tanzania, and South Africa.

Simmons explains that the safari is a “transcultural innovation that combined African and Arab travel methods with European notions of the hunt.” The word safari originated from Swahili and Arabic; both languages had words connoting voyage or discovery. Technological advances in transportation, including steamships and the completion of the Suez Canal in 1869, enabled Europeans to travel from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea, ending up in Mombasa, Kenya, where “clubs, a gymkhana (sports club), a well-appointed race course, luxury hotels, cricket and polo fields, and golf courses, all beautifully kept and frequented by white settlers” awaited them. From there they would embark on the next phase of their journey into the interior of the continent via the Uganda Railway, a controversial and expensive project that one critic called the “lunatic line.” From the train cars travelers saw a landscape “teeming” with wildlife. Simmons quotes Winston Churchill describing the railway as “a slender thread of scientific civilization, of order, authority, and arrangement, drawn from across the primeval chaos of the world.” The whole affair appealed to those who “were attracted by colonial fantasies, ideas about exotic Africa, nostalgia for the great past age of exploration and adventure, and admiration for what they regarded as the beneficent effects of the British colonial project in Africa.” Safari satisfied their desire for a “natural environment increasingly … seen as healthful, beautiful, and reinvigorating, a reprieve from the trauma of rapid industrialization and urbanization in the West.” (Before the creation of the railway, safaris relied on human porters to transport supplies, a truly hellish job considering the hazards of foot-based travel at the time, which included malaria and sleeping sickness, a disease spread from the tsetse fly.)

Safari tourism created an entire industry in the service of Europeans, including stores for supplies and clothing, taxidermists, travel agencies, and so forth. The foundation of the industry was the labor of Africans and Asians. Laborers from India were brought in to build the Uganda Railway. Africans were “guides, trackers, skinners, porters, cooks, guards, drivers, servants, camp attendants, and general assistants” and “professionals in the full sense of the word, working in the industry their entire lives” even as their people were “forcibly relocated” to create tourist areas. Their labor produced wealth that allowed the industry to become “a leading sector of the East African colonial economy.”

In the 1920s and ’30s, the years corresponding to the Great Depression and the time between the two World Wars, technological developments helped the safari industry stay afloat: advances in optics (cameras and binoculars) and improvements in wildlife photography; filmmaking, which saw the rise of wildlife documentaries; and air travel. During this time, “royalty, celebrities, plutocrats, and big-spending filmmaking productions … provided invaluable publicity and shored up the profits of the safari industry.” American filmmakers Martin and Osa Johnson, whose films achieved critical success, embarked on an “immense” undertaking in 1924, utilizing “six Willys-Knight cars with customized safari bodies, four lorries, five muledrawn wagons, four ox-carts, and some 230 porters” to transport, over 500 miles, “255 crates of supplies, including eighteen guns, twenty-one cameras, and large quantities of supplies, photographic equipment, camp furniture, tents, and food.” Just a decade prior, in 1909-10, Theodore Roosevelt had made his famed Smithsonian-Roosevelt African expedition, during which he and his son killed 512 animals (some brought back to American museums) at an estimated cost of the equivalent of $1.5-2 million in today’s dollars. Roosevelt’s crew also included professional photographers eager to demonstrate the advances of wildlife photography and filming. In 1926, George Eastman, of Eastman Kodak, went on a four-month safari. Ernest Hemingway wrote Green Hills of Africa based on his safari in Tanganyika (1933-34). “Hemingway relished the hunt. He killed three lions, a buffalo, a rhino, a kudu, and twenty-five other animals during seventy two days in Africa,” Simmons writes. Hemingway also suffered a dangerous bout of dysentery, or intestinal infection, from which he eventually recovered. He mentions it only briefly in the book. Simmons points out that this was “not the kind of story Hemingway wanted to tell.”

In Green Hills Hemingway portrayed himself in ways reminiscent of the “gentleman hunter” of the “leisure class.” He noted the following about the noble ethics of the kill: there was to be “no killing on the side, no ornamental killing, no killing to kill, only when you wanted it more than you wanted not to kill it.” He seems to have had a romantic idea about hunting, observing that it was like writing or painting, this essential thing you had to do as long as there was available game, the way one wrote or painted as long as one had pencil and paper or paint and canvas. He characterized the African landscape as “like an abandoned New England orchard to walk through.” (Of course, the area had likely been abandoned under more malignant circumstances. Hemingway noted seeing African people walking to escape famine. It turns out that periodic famines, as well as chronic undernourishment, were a feature of colonialism, as Rodney explained.) Hemingway clearly got enjoyment out of the horns of animals he’d killed, even though his jealousy comes through when describing the horns on a fellow hunter’s kill. The horns were “the biggest, widest, darkest, longest-curling, heaviest, most unbelievable pair of kudu horns in the world. Suddenly, poisoned with envy, I did not want to see mine again; never, never.” He also described killing the creatures: “This new country was a gift. Kudu came out into the open and you sat and waited for the more enormous ones and selecting a suitable head, blasted him over.” He described the dead kudu bull: “He smelled sweet and lovely like the breath of cattle and the odor of thyme after rain.” He wrote that he was taking back horns for his “wealthiest friends.”

From Hemingway’s account, one understands that this kind of hunting was dangerous and time consuming. Hemingway and his native guides needed tips and information from other native people in the area to know where to pursue the game. The party had to note which direction the wind was blowing to avoid being smelled by an animal, which could charge at the party before or after it was shot. They used a “blood spoor,” or bloodstain, to determine the animal’s whereabouts. The color, the wetness, and the quantity of blood all gave clues as to how briskly the animal was losing blood and in which direction it might have headed, and after how much time. After the hunt, which often left the party dehydrated and exhausted, they would sit around with food (canned fruits, meat from their kills), beer, and books—all transported by human porters—and eventually doze off under the shade of a tree. (Hemingway’s treatment of Africans, generally regarded as racist, swung wildly from friendly to mocking to homicidal. One “savage” he made fun of by calling the man “Garrick,” alluding to British actor and playwright David Garrick because the man pantomimed to communicate. Frustrated during a difficult hunt, Hemingway wrote, “If there had been no law I would have shot Garrick.” This is not even getting into the sexism toward his wife, who is referred to by her initials P.O.M. (“Poor Old Mama”) or as a little dog (“a little terrier”), or his offhand remarks about Muslim people. An updated edition of the book released in 2015 includes diary entries by Hemingway’s wife.)

The 1920s and ’30s marked the beginning of national park formation on the continent. The oldest colonial national park in Africa, Virunga National Park, in present-day Democratic Republic of Congo, was created by the Belgians in 1925.2 Kruger National Park was formed at the turn of the century as the Sabi Game reserve and formally named Kruger (after Paul Kruger, the head of the South African Republic, which was an independent republic derived from descendants of Dutch-speaking inhabitants until 1902, when it was annexed by the British after the Second Boer War) in 1926, and is one of the continent’s largest national parks. Dlamini notes that in 2009, half of Kruger National Park was under a “land claim,” which means a dispute over the land by locals which has been verified by the government, a process legally created in 1994 at the end of apartheid (the Restitution of Land Rights Act 22). Then South African President Jacob Zuma issued, in 2009, an injunction that all land claims were to be compensated financially since Kruger was considered a “national icon” that had to be preserved. There are still Kruger land claims under review, although a number of them were settled financially in 2016. It turns out that the game reserve I visited with my partner in 2019, Manyeleti, which is just outside Kruger National Park, is claimed by the Mnisi community, who settled there in 1922 for “grazing and subsistence farming” but were removed in 1964 “without their consent or compensation.” One academic report from the Netherlands notes the complexity of the claim on Manyeleti, specifically around who gets to be a claimant. It appears the claim is not fully resolved at least as of 2019, although the reserve’s web site notes that it is “owned and managed by the local Mnisi tribe. They successfully claimed the land as they have been living in the area for many generations.”

In 1933, the British passed the “Convention for the Protection of the Flora and Fauna of Africa, which called for the creation of national parks in Africa,” writes Gardner. A string of national parks followed in Kenya in the 1940s. In Tanganyika (Tanzania), Serengeti National Park and the nearby Ngorongoro Conservation Area were created in 1959. Gardner’s Selling the Serengeti tells the story of Tanzania’s Maasai people, who are semi-nomadic pastoralists (a way of life that relies on livestock that must be moved around periodically to graze). They have struggled under colonial and postcolonial governments to maintain land rights and to maintain their lives on their ancestral land according to their traditional ways of life and in the face of state-sponsored and Western market-based ecotourism and conservation projects. Theirs is a story to which we will return.

Safaris That Don’t Involve Killing Things

Safaris for non-hunter tourists often appear on travel bucket lists and are expensive. (While the U.S. has a number of “Safari Parks” that feature exotic animals, the discussion here pertains to safaris in Africa.) One tour operator lists price ranges for the safari itself and they start at around $400 per person per night. A look at one award-winning “super-high-end tour operator” (price listed as “from $7,500 per person for a ten-day trip”) is instructive. They show you how you can follow in the footsteps of safari-going former presidents and Hollywood celebrities. What’s more, “your safari will change a life” via the company’s nonprofit that helps African school children’s education. This messaging sounds fairly standard for modern times, when, increasingly, consumption of products and experiences is transformed into social uplift or social justice. (For example, RED, which was co-founded by Bono in 2006, boasts a collection of products and experiences the proceeds from which go toward The Global Fund, a private financing group founded by Bill Gates and others that aims to “defeat” HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria. You can purchase products like “earth rated” bags for doggie poop or a $3,250 gita robot that doubles as a walking buddy and a cargo carrier.) What Gardner writes to describe tourism in the Serengeti, we could apply to African safari generally: “It is a particular form of consumption in which the landscape is the commodity itself.”

Safaris are a form of ecotourism, which includes activities like visiting national parks, cultural heritage sites or monuments, or other natural areas of interest. One 1991 New York Times article noted the rise of ecotourism. “Born of the environmental movement, ecotourism promises the traveler an opportunity to help save the planet and get a suntan in the process.” According to The International Ecotourism Society, ecotourism is “responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment, sustains the well-being of the local people, and involves interpretation and education.” Gardner writes that “high-end safari companies attract tourists who are willing to pay extra for an exclusive experience that they believe has a positive impact on the environment and the local communities.” Safari is often billed as a boon for conservation. Now there is talk of regenerative travel, or “leaving a place better than you found it,” but this sounds like a marketing plan to revitalize the tourism industry, which has been “decimated by the pandemic,” a loss to the tune of $3.4 trillion. The New York Times reported in September of 2021 that “the loss of international tourism in Kenya and other East African nations, with little assistance from local governments or elsewhere, has decimated the livelihoods of thousands of travel and hospitality workers, who have had to take on odd jobs and borrow money to survive.” Travel bans around the Omicron variant of the coronavirus have affected South Africa particularly hard as well, where the pandemic is said to have “brought the hunting and ecotourism sector of South Africa to a complete standstill.”

Generally speaking, a safari’s main feature is the game drive. Two guides—a driver and a tracker (someone who looks out for the animals)—take a group of tourists out in a 4×4 for a few hours to see large game. The vehicles can get fairly close to the animals—within a few feet—which the guides say is safe because the animals have been desensitized to people (we got close to lions more than once, which is unnerving when you stop photographing the creature and actually think about the situation). The drivers are in communication by walkie-talkie, so they can alert each other to salient findings in the bush. In my personal experience, safari focused on Big 5 and other big game to the exclusion of much other wildlife. To say this is not to slight safari tour guides, who are certainly catering to tourist demand as defined by private tour operators. We had requested a bird guide on our safari. In order to accommodate our request, the guides separated us from the other riding groups. It was fairly obvious why: the search for birds would detract from prime Big 5 viewing experiences of the other tourists, which, certainly, was not going to be acceptable from a customer service standpoint. But this separation was slightly awkward because it made us seem like tourist-divas when in reality we wanted to see the big game, too. We just didn’t want to see Big 5 to the exclusion of, well, birds and everything else.

Consider this online customer testimonial taken from the web site of the private reserve in South Africa where my partner and I went on safari:

I saw the big five within two game drives. … Enough said right? Let’s just say I saw wild dogs mating, went on a hunt with a leopard and saw him pursue and kill a warthog, and a pride of lions?!?!?! Crazy right? … This is the place for people who like being out in nature but not having to rough it in any way! The food is three course and the guides make you feel at home. I didn’t suffer a single mosquito bite and was able to fall asleep to the sounds of nature (sometimes lions right near my tent… ) and then was awakened with the rising of the sun.

Manyeleti private game reserve, where we stayed, abuts Kruger National Park, an area which is said to be home to a great variety and number of species. One checklist from the South African parks department lists 296 species, a fascinating list that includes bats, mice, shrews, and bush babies; a list of several notable tree species (I am partial to baobabs, of which there are several species, because of their unique oddly-shaped trunks that store water and because they stood out to me when I lived in Angola some years ago); and over 500 species of birds. To focus mostly on large game, for which popularity grew under colonialism, is to get a stunted and, well, colonial view of African wildlife and landscape. Would people pay as much for safari to learn about African shrews and trees? Probably not. In the cold calculus of market logic, getting a thorough understanding of African nature isn’t on the menu, likely because it hasn’t been made profitable and because tourists may come to the experience with a relatively limited view of the natural world in Africa.3

If safari ecotourism—and, by extension, the conservation it claims to promote—focuses on a few species of African wildlife, the focus is even less on individual animals. As Abraham Rowe wrote for this publication last year, “Conservation as it exists today pays little attention to the actual interests or well-being of wild animals, like an individual toad, cricket, or giraffe, and instead places value in species. But species do not experience harms—individuals do.” Perhaps there is no better way to think about the lived experience—and suffering—of animals, as caused by humans, than by taking a look at trophy hunting, or “killing wild animals for their body parts.”

Trophy Hunting Safaris

Just as the colonialists “shot out” their game, so do modern safari operators who cater to Big 5 hunters. You need to buy “new blood,” as one operator explains in the 2017 documentary Trophy. Replenishing the stock, especially for “canned” hunting—the (in my opinion, sadistic) practice of raising animals in captivity for the purpose of hunting in a controlled environment—is key, because eager trophy hunters await the opportunity for another kill. The film gives a glimpse into the trophy hunting industry, showing the Safari Club International (SCI is headquartered in the U.S.) hunting convention, “the largest hunting convention on the planet.” According to the SCI web site, their mission is to “protect the freedom to hunt and to promote wildlife conservation worldwide.” In the film, an SCI leader explains that auctioned hunts raise funds that “go back into conservation.” The film then cuts to a woman at the convention. “Crocodiles are really mean. So I don’t feel bad about killing one of those,” she says. Besides, she confesses, she wants a purse, boots, wallet, and belt made out of crocodile skins. The prized goal for some hunters is the Big 5 Grand Slam. The film shows hunt prices ranging from $50,000 (lion) to $350,000 (rhino). As one Times writer put it: “Big-game hunters operate in a separate world from weekend deer hunters in the United States.” It’s an “elite person” who can afford to purchase “plane tickets, specialized gear and weapons, safari guides and astronomical hunting fees determined by what kind of animal you want to kill.” “These are salt-of-the-earth people,” one tour operator says in the article. “They may be wealthy, but people who hunt consider themselves conservationists.” As the saying goes, “if it pays it stays,” referring to the argument that hunting promotes species conservation.

Trophy hunting is legal in over a dozen African countries, with the most popular destinations being South Africa, Tanzania, Botswana and Zimbabwe. (Trophy hunting was banned in Kenya in 1977.) According to Gardner, a typical 21-day hunting safari in Tanzania, which offers seventy species to hunt, cost $50-150,000 in 2010. Once you take into account the various fees, “estimates suggest that a single visiting hunter brings in anywhere from fifty to one hundred times more revenue than a non hunting tourist.”

Notorious American Big 5 hunters include the Trump sons Don, Jr., and Eric as well as Walter Palmer, a Minnesota dentist who paid around $50,000 to kill a “celebrity lion” named Cecil in 2015 in Zimbabwe (which sparked “outrage around the world,” but not so much, apparently, among local Africans). The U.S. plays an outsize role in trophy hunting, as we “import more animal trophies than any other country in the world,” estimated at “over 650,000 trophies in 2017 alone.” As noted in The Hill article:

When most people think of a hunting trophy, they imagine elephant heads and tusks, maned lion mounts and leopard skins. But U.S. trophy imports include everything from fish and birds to reptiles and lots of mammals. It can get bizarre: baboons stuffed with a hand held out to hold your keys, or 7-foot-tall giraffe neck-and-head mounts. Some of these ‘trophy’ species are listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Roughly 640 foreign species are protected under the act (although many are not trophy hunted). While the Endangered Species Act does not stop U.S. citizens from killing these species in other countries, it generally prohibits imports of endangered species and allows for a prohibition on the import of trophies taken from threatened species. Yet, trophy hunters still bring in the bodies, heads, tails, legs and skins of threatened and endangered species all the time. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service permits these imports under an exception limited to activities that ‘enhance the species’ survival.

Furthermore, according to Trophy, 70 percent of hunters in the South African market, one of the largest, come from the U.S. and Canada. These statistics belie another reality: that fewer than a third of Americans surveyed in 2019 said they approved of trophy hunting (a much lower number than the approval ratings for hunting for other reasons).

In 2017, President Trump reversed an Obama-era ban on imports of elephant trophies (African elephants are endangered) killed in Zimbabwe and Zambia and then qualified the reversal in 2018 by announcing a “case-by-case” review of the imports. Although President Biden had previously expressed a desire to limit hunting imports, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recently announced it would permit some trophy imports again. The UK has plans to ban the import of trophies, which Boris Johnson has called a “disgusting trade.”

One idea explored in Trophy is that what used to be a “sport” is now “just killing,” as pointed out by American ecologist Craig Packer, who has studied lions in the Serengeti. The idea is that if the hunt is too easy—there’s no “fair chase”—then it could be objectionable. But the distinction between sport and just killing is meaningful only for the human involved. As pointed out by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA):

Hunting is often called a sport as a way to pass off a cruel, needless killing spree as a socially acceptable, wholesome activity. However, sports involve competition between two consenting parties and the mediation of a referee. And no sport ends with the deliberate death of one unwilling participant.

The reality is that hunters nowadays, just like in the past, go out of their way to kill animals. Hunters book flights and safaris to private reserves on the other side of the world in order to stalk and kill a creature that has their name on it. Canning doesn’t make hunting less cruel; it makes it more calculating, which, in a sense, makes it worse. It says something unsettling about the human doing the killing. (This situation is reminiscent of arguments about the cruelty of the death penalty, in which someone’s death is pre-ordained and they suffer the anxiety of knowing this, which, it could be argued, is a form of torture or cruel and unusual punishment inflicted upon the person. The animal in question, of course, doesn’t know it has been ordained to die, but the cruelty of the hunter’s premeditated actions is still significant in this light.)

Ultimately, doesn’t the creature suffer whether it’s killed for sport or just killing? In another scene in the film, a hunter from Texas has made his way to a reserve to hunt. He and the guide have identified an elephant that is too small to be a trophy. It will be killed and given to the local community as part of a “quota” arrangement with the safari company. After the initial shot, the elephant falls onto its side. The poor creature lies groaning, breathing heavily, eyes blinking. The men hover around it. The guide tells the hunter where to shoot. He shoots. Another groan, along with deep breaths, and then eventually the elephant goes still.

Hemingway’s companions described a wounded animal’s vocalizations in the following way: “It was wonderful when we heard him bellow. … It’s such a sad sound. It’s like hearing a horn in the woods,” Hemingway’s wife said. To which another man on the safari responded, “It sounded awfully jolly to me.” Hemingway also noted scenes of shot-and-dying animals: “Nothing could be more jolly than the hyena … who raced his tail in three narrowing, scampering circles until he died.” Or “the classic hyena, that, hit too far back while running, would circle madly, snapping and tearing at himself until he pulled his own intestines out, and then stood there, jerking them out and eating them with relish.” Or the “deep, moaning sort of groan … like a blood-choked sigh” of a dying rhinoceros.

One of the quietly disturbing parts of Trophy is when they show the cosmetic touch ups performed on the dead animal to prepare it for a photo shoot. The guides pour bottled water over the gunshot wounds to wash away the blood; they kick dirt onto large droplets of blood (or flesh) that stain the dirt around the animal; they prop up the creature to position it just so. The hunter is photographed in a position of domination over the lifeless and sanitized creature.

Another way to cleanse the debate about hunting is to argue that it aids conservation. “Hunting is the most successful tool for maintaining incentives to conserve lions,” wrote two SCI leaders in a 2011 op-ed. They argue that hunting in Africa brings in $200 million annually and that this “gives wildlife value,” as if wildlife have no intrinsic value or other right to exist. If lions cannot be hunted, they argue, lions will not have value, and then people cannot pay to protect them, and so inevitable wildlife-people conflict will cause people to kill all the lions. Thus, hunters are “truly the greatest stewards of our wildlife.”

Packer, the ecologist, counters this assertion in Trophy. About hunting in Africa, he says, “in many places, the economics don’t add up.” He also authored a 2011 paper which found that trophy hunting led to declines in lion populations in Tanzania due to “poor” management. The paper recommended a numerical limit on lions hunted. Even this kind of argument, though, reduces the issue to a calculation, similar to the SCI authors’ assumption that only a market price can impart value onto something or ought to guide our actions. This resembles “economistic logic,” which, as Nathan J. Robinson has written, “in the absence of a clear moral understanding of what creatures deserve, can lead you to justify the most horrifying things imaginable.” (For the creatures being hunted—or butchered, as I will explain below—such experience could very well be the animal equivalent of horrifying.)

But as Kevin Bixby writes in “Why Hunting Isn’t Conservation, and Why it Matters” (featured on “Rewildingearth,” a conservation website):

It is a question of equity. Everyone benefits from wildlife, everyone should share in the cost of protecting wildlife, and everyone deserves a say in determining how best to conserve wildlife. If hunters’ claim that they pay more than their share for wildlife conservation is true, the solution is not to exclude others from a seat at the table, but to find new, more equitable sources of funding to support the work.

While Bixby was specifically writing about the situation in the U.S., the logic applies to trophy hunting in Africa. Furthermore, he writes:

Hunters and their allies are quick to assert that wildlife management decisions should be dictated solely by science, not emotion, as if science could adjudicate among what are essentially value matters. Science can tell us, for example, how many mountain lions can be removed by hunters without causing an unsustainable decline in their numbers, but it can’t tell us whether we ought to be hunting mountain lions in the first place.

The idea of harming some creatures to save more of them is the same argument used in the effort around rhinoceros conservation, which is also explored in the film. John Hume, a famous rhino breeder in South Africa, says that dehorning rhinos every two years—a procedure involving sedating the creature and sawing off its horn—saves the creatures’ lives because they are not valuable to poachers without their horn. There is a lucrative market for rhino horns, which have been thought to possess medicinal properties in some forms of traditional medicine in Asia. Rhino horn, made of keratin (which makes up human fingernails), is “more expensive than gold or heroin by weight,” Hume says. He also insists: not one creature that people breed goes extinct. While this might be technically true, on grounds that something being bred continues to live, we have to ask under what conditions the animals are allowed to live. Hume insists dehorning is painless, but mutilating a creature on a scheduled basis does seem “like a brutal process”—because it probably is. The general idea in articles about rhino dehorning is that it is appears to be a “harmless” process, similar to trimming one’s nails, but this seems like a very anthropocentric interpretation—how do we know that drilling a thick rhino horn with a saw is experienced by the animal as inconsequentially as we experience the filing of our nails? Not to mention the animal has then been deprived of the use of its horn for social or behavioral or other purposes.

What about the harm to the individual animal in the calculus? To return to Rowe: ”It is a spectacular moral failure that we do not act to address the vast animal suffering occurring in the natural world, human-caused and otherwise, and instead focus only on increasing biodiversity and protecting wild spaces. While the current goals of conservation are important, they miss something fundamental: that wild animals are individuals with their own needs and concerns.”

Where proponents would consider the harm to the animals, it’s in comparison to poaching. Trophy observes that the yearly animal deaths by trophy hunters (1,100) constitute but a tiny fraction of the animal deaths caused by poachers (30,000). (Dehorning advocates note that the poacher has no economic incentive to kill the rhino if it has been dehorned.) But this argument is a form of lesser-evilism at work. Whenever we’re dealing with harmful behavior like poaching, which is presented as criminal, we need to ask: whose harmful behaviors are legal and whose are illegal? If killing an animal that we don’t have to kill causes it to suffer, and if suffering that can be avoided is therefore harmful and even undesirable, then why is it legal for a wealthy (often white) man to do it on a hunting safari but illegal for, say, an African poacher to do it, whether that person is part of a larger criminal network or just an individual looking for a way to make money? I find it hard to see trophy hunting as noble and poaching as depraved.

Poaching is clearly a complex problem that people can reasonably agree needs to be addressed. It’s not hard to understand why people in economic need might turn to illegal activities to meet their needs (poverty is indeed one reason people go into poaching). This is a basic observation abolitionists on the left make all the time in regard to what drives people to commit illegal acts that cause harm. At the very least, we need to focus on all aspects of the treatment of wildlife by people: how can harm be reduced? If we focus on reducing harm for all animals and people, we don’t have to trap ourselves in the we have to kill or harm to save mode of thinking.

Ultimately, despite the claim that hunting is so beneficial for conserving wildlife, the Big 5 are not doing so well at the species level. According to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species: the buffalo is threatened, the lion and leopard are vulnerable, the elephant is endangered, and the black rhinoceros is critically endangered.

Maasai Case Study: The Market ‘Solution’ to Dispossession

Gardner, an American professor of geography, spent nearly twenty years researching and living in Tanzania to write Selling the Serengeti. He studied how tourism affected the Maasai people in the Loliondo division, a tourist hotspot in the north of the country, located east of Serengeti National Park and near the border with Kenya. The story of the Maasai people is instructive because it illustrates many of the problems with Western ecotourism/conservation on the continent, as well as highlights African perspectives on the issues.

Gardner interviews a number of Maasai leaders, villagers, and activists. Some notable quotes give a sense of the thinking behind Maasai actions over the years:

- “Conservation are the people who stole our land.” —a man Gardner shares a car ride with, 1992

- “We don’t want tourist money. We want our land.” —Lucy Asioki, leader of a women’s organization in Loliondo, 2010, in response to Thomson Safari lease of Maasai land

- “What we need are real private sector partnerships that empower us.” —activist David Methau (a pseudonym), 2008

The Maasai are “one of the world’s largest ethnic groups,” and their population is spread over Tanzania and Kenya. They have “strict taboos against hunting and eating wild animals,” Gardner writes. They do, however, hunt lions on occasion. Since they practice a traditional way of life that requires them to access land throughout which their livestock can disperse (they also depend on some small-scale agriculture), they have resisted fortress conservation efforts over the years yet have cooperated with some private tourism projects in an effort to take advantage of contracts, which they believe will strengthen their claim to their land (and even earn them property ownership under the law). Just under 25 percent of Tanzania’s land is “under state protection and control as either a national park, a game reserve, a forest reserve, or a hunting concession.” Gardner writes:

Without Maasai stewardship … much of the current wildlife habitat in many of the country’s national parks, as well as in adjacent areas like Loliondo, would not exist. Once vilified as a destructive land use, since the late 1980s pastoralism has come to be understood as the livelihood system most compatible with wildlife. Unlike agriculturalists, who directly compete with wildlife habitat for productive land, pastoralists typically manage their rangelands in ways that support both wildlife and livestock.

The Maasai have essentially faced the threat of a “global land grab” from colonial times onward. Over the years, the government has enclosed their land and even evicted them, tried multiple times to convert their land to other uses in a series of failed projects (sometimes aided by the U.S.), and allowed neoliberal notions of private property and market value to be placed onto traditionally communally held land. The rise of modern conservation and neoliberal market policies and structural adjustment programs (SAPs) of the ‘80s led to increased foreign investment in the region, which ultimately led to the commodification of wildlife and landscape. Throughout this time, the Maasai have organized and demonstrated against initiatives that would hurt their access to land.

The area that would become the Serengeti National Park (SNP) and Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA, which is home to a large crater) was created by the colonial Game Ordinance of 1940. Although the colonial government said that the Maasai would be able to live there, they eventually placed restrictions on peoples’ movement and on burning and hunting, and they banned agriculture outright in 1954. Even though the government let up on some of these restrictions in later years, for people around Loliondo, the NCA “came to symbolize loss of pastoralist land and rights through state-led conservation.” Gardner discovered that Maasai often used the word “conservation” to refer to the government agency that manages the NCA.

Researchers from the Oakland Institute, a think tank that published a report about the Maasai’s plight in the region in 2018, interviewed villagers in the Ngorongoro district. One anonymous villager had this to say:

We are Tanzanians but the laws that govern the others do not apply to us. Instead, we are still governed by the colonial laws of the past. The Maasai, chased from the Serengeti, were tricked into believing that we will have Ngorongoro as compensation and that we will never be evacuated from here. We were even promised priority in a case of conflict. But today we cannot use the land for grazing or for cultivation—the end result is starvation of our families. The only use left for this land is to be our burial ground. … We were then promised food aid. But little assistance came and when it did, leaders sold it at exorbitant prices. So we live in dire poverty and face malnutrition. Families have sold cows to buy food. With cattle gone, nothing more is left. Men have been forced to look for jobs in urban areas. They work as night guards in South Sudan where several have been killed. Poverty, hunger, and illiteracy have increased. There is no money for education and those who go to school are still starving. In 2012-2013, close to 500 children from 30 villages, faced with malnutrition, were taken to the hospitals. … Hunger is a sensitive political matter in the village and we are not allowed to speak of it.

Tanzania gained independence from the British in 1961, and its first President, Julius Nyerere, a socialist, became leader in 1964. His main program was ujamaa (Swahili for family bond) socialism or “villagization,” in which the government attempted to unite different ethnic groups into villages in which democratically elected representatives could manage the interests of a diverse group and which could function as socialist agrarian collectives (Nyerere believed the country had to begin producing food crops to modernize). People were even pressured at gunpoint. The Indian Marxist historian Vijay Prashad has referred to Tanzanian socialism of the period as “typical of the ‘socialism in a hurry that became undemocratic and authoritarian.’” In Maasailand, villagization took place later than in the rest of the country, as government officials initially avoided efforts in places they saw as potentially noncompliant. Villagization was potentially incompatible with pastoralism, which required “dispersed” peoples to manage resources such as salt, water, and grass for livestock. Gardner notes that the government failed to understand the distinction between concentrating people for social services delivery and dispersing livestock to “safeguard the range land from the destructive power of large herds.”

Over the years, there were various failed projects in Maasailand—one to convert the Maasai into ranchers, and another to grow barley on the land in order to service the beer industry. The 1964 rancher project was largely an influence of USAID, created with the idea that the Maasai could produce meat for export to Europe and other countries. The project failed due to overgrazing and problematic water sourcing. When USAID got formally involved with the project in 1970, they shut down their efforts after ten years. The barley project was a state-run project from 1987-89. That, too, failed because of lack of adequate rainfall and the remote location making transportation difficult. After the government abandoned the land for the barley project in 1989, Maasai people in the area agreed to share use of the land for livestock grazing and watering—that is, until 2006, when the owners of Thomson Safaris, a popular American safari tourism company, announced they had acquired (via their organization Tanzania Conservation Limited, or TCL) a 96-year lease on the land, completely taking it away from Maasai use without their prior notice or consent. One man, Ole Pertese, said people with the safari company came to survey his family’s homestead, telling him, “You can no longer use this land. It is the land of a mzungu [Swahili for white person], not of Maasai.” The Thomson lease triggered fierce resistance from the Maasai over the eight-year period in which Gardner covered the story, what he calls a “remarkable political achievement,” given that at the time the book was published in 2016, the legal issues were still unresolved. As Garder notes, Thomson Safaris claimed their project “preserve[s] fragile ecosystems and protect[s] vulnerable wildlife populations,” promoting the idea that the Maasai were destroying the ecosystem. Thomson also pitted ethnic groups against each other by hiring certain ethnic minorities over others and portraying the conflict as one about ethnic tensions, the latter which Gardner found to be largely unsubstantiated. The Oakland Institute report noted that the conflict between the Maasai and Thomson “rages on.” The report notes the “climate of fear” that has pervaded the area, as the Maasai have been subject to “violence, harassment, and arrest, at the hands of local police officers, who are called in by TCL for trespassing” on its nature reserve.

The neoliberal structural adjustment programs (SAPs) of the ’80s , writes Gardner, aimed to “reduce the role of the public sector, prioritize balancing national budgets, promote foreign trade, privatize state-owned companies, and rationalize social service provision.” This encouraged privatization of the hunting industry (the socialist government banned sport hunting from 1970-78 and had intended to nationalize the industry but never did). In 1992, the Dubai based Ortello Business Corporation (OBC) trophy hunting company gained hunting rights in Loliondo. OBC was required to do development projects (involving water and the building of primary schools and medical clinics), as was the trend at the time, as part of the agreement. However, a decade after initiation, “very few of the development projects initially promised by the OBC had been realized.” For some years, however, the Maasai tolerated the hunting because the company only used the land certain times of year, and initially people were still able to graze their livestock on the land; besides, the Maasai weren’t particularly concerned about the hunting of game. Eventually, things came to a head in 2009, when a drought forced Maasai people to congregate in search of water outside their usual range. State police responded by evicting hundreds of people and thousands of cattle and jailing or harassing many people. It was an “unprecedented event in Loliondo.” Gardner notes that, “for many of the Maasai residents I interviewed, the OBC and the Thomson Safaris … land deals were considered a ‘government effort to complete the land grab started under colonial rule.’” (Gardner notes that “conservation refugees” exist all over the world; he cites one estimate that puts their number at “14 million in Africa alone.” One recent report by Minority Rights Group, a human rights NGO for Indigenous peoples’ rights, details the eviction of and violence against Indigenous groups in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, and India.)

The Oakland report also details events of 2017, when government-inflicted fires struck Maasai homesteads (also called bomas) around Loliondo and further worsened tensions between Maasai and OBC:

According to the Tanzanian Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism, the violent evictions began on August 10, 2017 and were set to last for two weeks. The Ministry’s press release notes that bomas were being burned under government orders, in order to preserve the ecosystems in the region and attract more tourists.

The same report noted that OBC’s license had been cancelled that year due to concerns of corruption, but a 2018 update noted that OBC was still active in the region. A 2019 document signed by the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the environment also noted that OBC maintained activity in the region.

In the ‘90s, direct contracts arose between villages and safari companies. This was seen by the villagers as a way to cement their own land rights, since under these agreements, they could still have access to the land. The Maasai thought they, not the government, should negotiate the terms of use of their land; the government they saw as a force that would only take away their land and livelihood. In 1991, Dorobo Safaris, owned by expatriates, started to contract directly with villages, essentially leasing their land for tourism use. The villages would receive direct payment, which they could use to build schools and meet other needs. Around this time, some villages around Loliondo got “legal title deeds for 99 years” for their traditional land, which was seen as a win. But in the early 2000’s, the government declared direct contracts with companies to be illegal; they started enforcing the policy some years later (although Gardner noted that not all companies “responded” to the enforcement). He writes that “a large number of Maasai leaders and citizens have embraced village-based tourism contracts despite such agreements’ uncertain and unfulfilled promises.”

So where is all the money going? To quote Rodney:

Under colonialism, the ownership was complete and backed by military domination. Today, in many African countries the foreign ownership is still present, although the armies and flags of foreign powers have been removed. … In other words, in the absence of direct political control, foreign investment insures [sic] that the natural resources and the labor of Africa produce economic value which is lost to the continent.

Putting together Gardner’s and Rodney’s analyses, we can clearly see that the economic extraction of conservation ecotourism has inflicted great harms upon the Maasai, who continue to protest government efforts to expand conservation areas.

Moving Past Bourgeois Tourism

Some years ago, I spent a year living and working in Luanda, Angola, a sub-Saharan city of over 2 million people (Angola was a major point of departure in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade) as part of an international health program. The country had gained independence from the Portuguese in 1975 and then endured a 30 year civil war which ended in 2002. The countryside remains littered with landmines, which tend to leave people as amputees if they manage to survive their encounter with the deadly explosives. The inequality there was stark and visible. Nearly half of all Angolans lived on less than $2 a day in a city noted to be, at the time, one of the most expensive cities in the world for expatriates. I lived in a gritty urban midrise, probably a Cold War-era building, that had a busted elevator and stairs so worn they were depressed in the middle. Sometimes there was running water, but mostly not. Tin roof neighborhoods—settlements called musseques—abutted a $500 a night hotel a couple of blocks from where I lived. My neighbor was a Portuguese woman who had relocated from Lisbon to escape the unemployment and austerity of the eurozone crisis there. The hospital where I worked had a small library, where I went sometimes to read. Bookshelves held textbooks and some international medical journals. Outside the window I could see the reddish-colored dirt of the musseque, small people moving in the distance. All this knowledge, I thought, yet such extreme poverty and inequality. At the time, I became disillusioned with the Western NGO-private corporation approach to international health in the Global South.

Around that time, the then president’s daughter, Isabel dos Santos, became the continent’s first female billionaire. She was later caught up in a corruption scandal. Angola may not be a safari destination—indeed, Westerners need a visa and a good reason to be allowed in—but the country is impacted like others on the continent by the continued extraction of its wealth, often by its own leaders who are aided by the West, and by Western corporations (oil and gas companies active in the country include Total, Exxon Mobil, Chevron, and BP) that distribute this wealth in the form of compensation packages to expatriate employees in the country as well as to their shareholders. Colonialism may have formally ended, but now we have capitalism (fueled by extraction of natural resources, in Angola’s case—oil and diamonds) and corruption to continue the tradition.

African nations generally suffer disproportionately from global wealth inequality and tax avoidance. Despite decades of international development goals, including the UN Sustainable Development goals, the #1 of which is to “end poverty in all its forms everywhere” with a 2030 timeline, poverty remains at persistently high levels, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, and these levels are expected to worsen throughout the course of the pandemic (WHO reported that a mere 9 percent of all Africans had been fully vaccinated against COVID as of late 2021, in no small part due to wealthy countries hoarding vaccines). There’s also the “bottomless bottom-line cruelty” of the IMF and the World Bank, which keeps poor countries poor and in a state of debt servitude. Almost all of the world’s poorest countries are in Africa.

As French economist Thomas Piketty argues, we need to tax global wealth to tax billionaires out of existence. Beyond returning stolen art and artifacts to former colonies, the West owes Africa for what the imperial powers took from the continent and continue to extract today. This cannot be made up by bourgeois tourism,4 particularly when safari companies and lodges tend to be foreign-owned or otherwise white-owned businesses.

According to a 2022 article in Condé Nast Traveler, “across the continent, black Africans have very little stake in the safari industry—most owners (and, in South Africa especially, managers and guides, too) are white. The African Travel and Tourism Association estimates that at most 15 percent of its 600-plus members are black owners.” Most companies on Travel + Leisure’s top 10 safaris for 2021 list (notably, a survey-based list biased by its respondents’ experiences) appear to be owned by white people (whether from Africa or outside of Africa), and “the most profitable tour companies, lodges, and private game reserves surrounding the [Kruger National] park are owned and operated by whites,” according to a 2009 article in Slate.

Recently, I attended an online symposium by the Walter Rodney Foundation commemorating what would have been the 80th birthday of Rodney, who was assassinated in 1980 at the age of 38. At the symposium, Robin D. G. Kelley noted that Rodney’s How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, in detailing the extensive harms of European colonialism, presented a compelling case for reparations. The evidence in the book “exceeds” the U.N. standard for reparations, Kelley said. There ought to be more demands for reparations from the European colonial powers, such as happened recently when Prince William and Duchess Kate visited Jamaica on their Royal Caribbean Tour. They were received with demands from activists and leaders for reparations and an apology for slavery. The Prince gave a speech expressing his “profound sorrow” over slavery but, notably, did not apologize.

I have deeply ambivalent feelings about having been on a safari. I’d bought into something that was billed as a bucket experience to help save Africa for humanity but was the West’s idea of a commodified Africa. Safari ecotourism and trophy hunting, we’re told, will fund conservation for humanity and development for people in Africa in general. But did humanity vote on Western conservation? And what are Africans telling us in the West to conserve for humanity? (I doubt the U.S. would care to ask or listen.) All we do in the U.S. is develop and destroy.

One argument is that the human species tends to destroy other species, as we have done by killing to extinction other megafauna throughout the world. If we don’t consciously save the megafauna, by sectioning them off in discrete reserves, the argument goes, humans will kill all the creatures that threaten humans.5 Perhaps. But if killing is a constant (now and in the hypothetical scenario given), I cannot see how it is just or even fair to allow wealthy people to kill animals or to butcher them or to pay large sums to drive in cars to see animals so that we can say we’re saving other animals, meanwhile Africans, whose countries were held back from development by colonial powers for hundreds of years and who lost rights to their own land, work to provide these services to said wealthy people because development and conservation. You cannot fight the legacy of colonialism with neoliberalism, because they are cut from similar cloths.

The problem is not, as the enthusiasts of neoliberalism tell us, that nature has no value other than what the market will assign to it. The problem is that way of thinking and the growthism, excess of development, and anthropocentrism under global capitalism. You cannot realistically expect to conserve natural areas and wildlife by utilizing the same logic which has led to the destruction of nature. Recall that Kenya banned hunting in 1977, yet its wildlife habitat is under increasing threat from development and privatization of land, two tendencies that we see commonly in the West. (Banning trophy hunting is still good, in my opinion, but that act alone cannot stop the destruction of nature in other ways.)

The neoliberal choice forces us to accept the suffering and commodification of the vulnerable (people, animals, land) in order to supposedly save or uplift the same vulnerable living things. We have to kill some lions to save the rest. We have to butcher some of the rhinos to save the rest. We have to let Africans choose market schemes so that they can develop themselves out of poverty while mostly non-Africans (or white people) profit. We have to accept unsavory things because that’s how the world works—the lesser of two evils. But this is a false choice. It’s the same logic that says we should accept sweatshops because some job is better than nothing for the world’s poorest. It is also the same logic that says that the agents or institutions of harm will bring solutions to that harm. If colonialists inflicted destruction upon animals and the land (necessitating conservation in the first place) and underdeveloped a place, now their descendants (literal or figurative) will operate safaris to promote conservation and development. (Or, in the case of climate change, the fossil fuel companies will save us with their corporate responsibility.)

The subjugation of people and the commodification of land and living things is at least something we should agree is bad, and keeping African development tied to ecotourism and conservation certainly appears to keep Africans in a kind of colonial relationship with the West which is unacceptable. It’s one thing to support Indigenous people, such as the Maasai or the Mnisi tribe, in their decisions to contract directly with tour companies to sustain their livelihood. I would rather see the Maasai’s and the Mnisi’s material conditions improve than not. I would rather see the Maasai keep their land and way of life. But these kinds of market decisions, made under economic duress and without other alternatives, are compromises. They shouldn’t be seen as liberatory. (As a person from the U.S., I don’t claim to speak for Africans. Yet, as a concerned citizen of the world, I believe the evidence presented demonstrates that market conservation projects are not generally liberatory.) Our goal on the left ought to be the liberation of all peoples from economic, social, and political compromise under global capitalism.

Safaris, as conceived of and operated by Westerners, shouldn’t be a thing anymore. (Nor should “safari chic” as a fashion trend, a notable example of which was Melania Trump sporting a pith helmet on a 2018 visit to Kenya.) Trophy hunting (along with other forms of animal cruelty, like factory farming) needs to go, too. Safaris also shouldn’t be the things that fund conservation and development. I don’t think it’s anyone’s right to trophy hunt or go on safari. People don’t have the right to make other creatures suffer for no good reason other than their egos or some emotional rush. I don’t have any more right to see the last of the world’s great megafauna than Europe had in underdeveloping the continent of Africa to begin with. And as an anticapitalist, I am against peoples’ livelihoods and other living things’ existence depending on someone else’s profit, particularly when that profit extracts wealth from a continent that has endured centuries of exploitation.

If moving past a colonial and capitalist past and present requires learning different ways of relating to each other and to the natural world, we need to shed old practices, and that includes safari-going. We have to counter the colonial and imperialist tendencies alive in the world with a robust anticapitalist internationalism—the thing we need anyway if we want to have any hope of human survival on a warming planet. We need a different form of conservation. As Rowe put it: “Conservation could take a more transformative approach, and consider not only human interests, but the lives of all beings impacted by nature.” To do this, we need to center Indigenous people and knowledge. While Indigenous people do not embody a monolithic outlook (nor do they necessarily practice traditional ways of life), Indigenous communities tend not to destroy the environment the way capitalist societies do. In fact, although Indigenous knowledge and practices are routinely ignored in international conservation efforts, Indigenous people are the best conservationists. (The pastoralist Maasai in Tanzania were not destroying their land before the hunting and safari companies came to cash in on their resources. Other traditional African cultural practices may benefit ecosystems as well.)

On one of our last days on safari, we saw a memorable sunset on our evening game drive sundowner. The sky turned orange. We heard the strange horn-like sound of the Southern Ground-Hornbill, a bulky red and black bird. There was no sound pollution, nothing overhead, only sky and land in every direction. We drank dark amber-colored rooibos tea from tin cups. We looked around. The experience was nothing like happy hour.

Clarification 4/28/22: An earlier version of this article stated that OBC had lost its hunting license in Tanzania in 2017. It turns out that OBC has maintained activity in the region. The article was updated to reflect this information.

“Ivory” here is likely being used colloquially to refer to something valuable. Rhino horn is not made of ivory; it is made of keratin. Ivory refers to the substance that makes up the teeth and tusks of certain large animals such as elephants. ↩

The ongoing conflict in and around the park, involving armed groups, militarized park rangers, local inhabitants, and oil exploration companies was explored in the 2014 documentary Virunga. Virunga is managed by a partnership between the Congolese National Parks Authority and an EU-owned NGO, the Virunga Foundation. The park website notes that 4 million people live in the region, which is home to endangered mountain gorillas and designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. ↩

In his 1993 book The Age of Missing Information, Bill McKibben argued that television, particularly nature documentaries, does not give us very good information about the natural world because it obscures the reality of the limits of the natural world (an important thing to know if you want to do something about climate change, since unlimited natural resource extraction and consumption are incompatible with efforts to stop fossil fuel use) and focuses on drama and entertainment, instead of helping us to “understand that they’re [animals] marvelous for their own reasons, that they matter independently of us.” ↩

As Gardner writes, in 1970, Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere convened a student inquiry at the University of Dar es Salaam into “the merits and limits of pursuing tourism as a strategy for socialist economic development.” The students criticized what was seen as an effort “geared towards producing tourist goods” such as “tapestry for the hotel room, a fan, water-heater, or a whisky.” They predicted tourism would “reinforce colonial relationships” and would “mainly benefit the elites or the ‘international bourgeoisie.’” ↩

Human-wildlife conflict that results in human deaths or injury remains a problem, particularly in areas of habitat overlap. ↩