Randall Kennedy on Why Critical Race Theory is Important

A longtime critic of CRT, Kennedy explains why the central tenets of CRT are nonetheless important. He also discusses the myth that law can be “apolitical.”

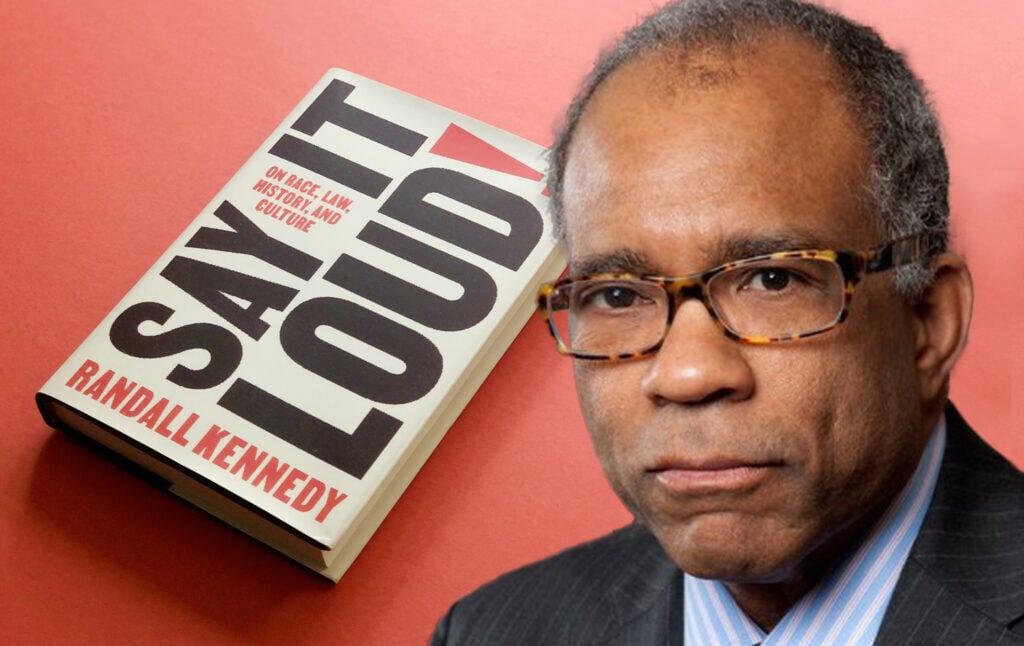

Professor Randall Kennedy of Harvard Law School is the author of a number of books, including For Discrimination: Race, Affirmative Action, and the Law, The Persistence of the Color Line: Racial Politics and the Obama Presidency, Sellout: The Politics of Racial Betrayal, and, most recently, Say it Loud!: On Race, Law, History and Culture. Kennedy recently came on the Current Affairs podcast to talk with editor in chief Nathan J. Robinson. This interview has been lightly edited for grammar and clarity.

Robinson

Randall Kennedy is always provocative, always fascinating. This new book, Say it Loud, covers everything from critical race theory to prison abolitionism to the career of Thurgood Marshall to an essay that I love called “Why Clarence Thomas Ought to be Ostracized.” Professor Kennedy, it is a delight to talk to you. Thank you so much for joining me.

Kennedy

Thank you very much for having me on.

Robinson

This book covers a lot of ground. I saw you recently on a Manhattan Institute panel about critical race theory. And I was really fascinated with your contribution. Manhattan Institute is pretty conservative, and they invited critics of critical race theory on the panel because the big thing that Republicans have been talking about is critical race theory in the schools. It’s a big issue in Virginia. And they had all these critics on including Christopher Rufo, who has been doing a lot to scare people about critical race theory. I think your perspective was the most interesting of the bunch. I’m not sure that they expected the take that you gave them. They invited you as a critic of critical race theory, I think, maybe expecting that you would concur with everyone there, who was talking about critical race theory as if it’s worthless. But you didn’t concur. And I think it’s very interesting. Throughout your book, you take ideas that you are critical of and deal with them in a way that is, to my mind, quite fair-minded. You see value even in things you disagree with. Critical race theory has been on people’s minds. You knew Derrick Bell, an early proponent of critical race theory. You write a whole essay about him, and your take on it, as I understand it—that you disagree with him but also find some value in his work—seems to have changed over time.

Kennedy

I’ll say two things about this. Firstly—this is apart from the substance of critical race theory. The campaign that is being waged against it is, in my view, abhorrent and dangerous and deeply disturbing. As we speak, there are now several states in the United States that have basically said that critical race theory cannot even be discussed in public schools, not just lower grades, but also in higher education. And so what we’re seeing is something that I think is a tremendous threat to learning, to academic freedom, to the freedom to read, and the freedom to think. And so that’s the first thing in my view of what’s been going on over the past few months. Let’s put quotation marks around critical race theory because, frankly, the people who are attacking critical race theory have concocted a boogeyman. They have put together a whole bunch of ideas that they think will be just totally unattractive. And they’ve attached the label critical race theory to that. And they’ve buffaloed people. Many people are unaware of and have never read anything about critical race theory. And so the critics have made critical race theory into a very unattractive idea and have attacked it in this way. And I think that’s very bad and very, very dangerous. So now let’s talk about critical race theory: the substance of ideas that have been propounded by people in legal academia and outside of legal academia. When I went on this program at the Manhattan Institute, I’m quite sure that I was invited on because I have written critically about certain features of critical race theory. They probably thought that I was going to damn it. But I did not.

In fact, I’m a little bit cross with myself that I didn’t come out a bit more aggressively in defense of some of the central ideas of critical race theory. There are two ideas that you don’t have to be a critical race theorist to embrace. One is simply the idea that racism has been pervasive and deeply entrenched in American life. Well, who can disagree with that? If you take a look at the most public activities—you know, voting, jury service—or even the most intimate activities like sex or marriage, race is everywhere in American life. And that’s one of the central ideas of critical race theory. It’s a good idea. It’s a very useful idea. And it has produced very useful scholarship.

The second idea is that the reforms of the second Reconstruction, the various anti-discrimination laws that were passed during the 1950s and the 1960s—some of the critical race theorists say that these reforms were welcome but not enough. Or inadequate. You don’t have to be a critical race theorist to embrace that proposition. I think that they are, again, correct. So there are very basic ideas within critical race theory that are useful, that are incisive, and that are productive. I think that there are people who call themselves critical race theorists who have written things that have certainly enlightened me.

Robinson

One of the things I like about your book is that you take a historical approach, and you ask us to understand ideas in context. So where did the term “critical race theory” come from? Where did this perspective come from? You talk about, for example, the optimistic versus pessimistic traditions in Black intellectual life and point out that, since the Civil War, and since the first Reconstruction, there has been a debate among Black Americans—between those who are roughly pessimistic about whether racism will ever go away and those who see this constant march of progress and look for the racial utopian promised land. And you encourage us to take those perspectives seriously, even if you are less of a racial pessimist than the critical race theory co-founder, Derrick Bell. You recognize that that pessimism comes from a place of the observation of real facts, that it is a legitimate perspective, and that it is not irrational especially given people’s personal experiences and observations of racism over the course of the 20th and now the 21st century.

Kennedy

Absolutely. In the essay that you mentioned—on optimism and pessimism and racial thought—that’s the essay that begins the book and I think that that struggle is probably the central intellectual struggle in the book. And I do count myself as an optimist though I am now not as confident as I once was. I’d say that I’m a chastened optimist, but I’m still in the optimistic camp. But one thing I do say is that the people who are pessimistic are smart people. It’s not like they just want to be pessimistic. Among the pessimists are Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Jefferson, Alexis de Tocqueville. And then among Black people, Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X. My father, whom I revere, was a thoroughgoing pessimist. And he was a smart man; he was a very observant man. The true tragedy is that the pessimistic view—the view that says, “unfortunately, we shall not overcome”— has a lot behind it. A person who has that view can point to a lot of things, including the ascendancy of Donald Trump. Here’s a person who openly trafficked in racial resentment, racial prejudice, racial bigotry, and he ascended to the White House. And then with respect to the reelection of Donald Trump, after he had shown himself to be a thoroughgoing bigot and thoroughgoing facilitator of bigotry, he almost won. Thank goodness he didn’t, but it was close.

Robinson

Yeah. If it wasn’t for the pandemic, he probably would have won.

Kennedy

Absolutely. And even losing, he got over 70 million votes. So people say, Gosh, if we’re going to change things, the change is going to have to come from sources outside of the conventional. The people who say that have a strong point. Again, I disagree. But I can’t just blithely say that they don’t have a point. They have a good point.

Robinson

One thing that is underappreciated about Donald Trump’s rise to power is the fact that his first entrance into politics was the birther conspiracy, which he rode for years. It was essentially his main political issue for the first couple of years in which he was talking about politics and was doing everything to delegitimize Barack Obama by suggesting that he wasn’t legally qualified to be president. Essentially, the claim was that Obama was a usurper. This was just a blatant racist conspiracy. And then through the strength of his public profile, Trump tries to undo as much of what Obama did as he could. There are very clear parallels with a period that you write about in the book, which is this so-called Redeemer period in the South after Reconstruction, which I think a lot of people still aren’t really taught about. We had a glimmer of equal rights for a short period after the Civil War. And then there was a massive [white supremacist] backlash to take it all back and to undo it. It succeeded [to give us Jim Crow]. And Donald Trump completely succeeded. Every time there was a step forward, there was a lot of backlash when you look at the history.

Kennedy

Absolutely. And we are in such a period now. Whether we will get to the other side in a good way is unfortunately a question. We cannot be assured that we will, but we are clearly in a period of racist reaction. Let me say one thing about the birther movement because this goes to an issue that’s very much in discussion today about the structure of American democracy. Donald Trump was able to mount his birther campaign, and it wasn’t just him. He was the one who rode it most effectively. But there were lots of others who were riding that horse, or trying to ride that horse. Where does that come from? What enables them to even make a claim that someone who was born abroad is ineligible to become President of the United States? That provision is in the United States Constitution. And, in fact, in my book, I have a chapter about it. It is an invidious discrimination that is built in to the United States Constitution. Americans are very happy to talk about the American creed. We welcome everybody in America. If you embrace certain ideals, it doesn’t matter where you came from. Not true. If you were not a native-born American, you cannot become President of the United States. What that means is that there are millions of people who are American citizens who cannot become President of the United States. There are people who are buried in Arlington National Cemetery, who have given their lives in defense of the United States of America, and they could not have become President of the United States because of a provision that is in the United States Constitution. It is an invidious discrimination. People have complained about it. I certainly have complained about it. There are people of all sorts of ideological persuasions who have complained about it. Has anything been done about this? No. And nothing will be done about it in the foreseeable future even though this is a terrible, invidious discrimination against millions of American citizens that is built into the United States Constitution.

Robinson

Well, you won’t find any disagreement from me. I’m actually disqualified under this provision as well because I was born in the United Kingdom. So there are two tiers of citizens: the citizens who can be president and those who can’t. I think it’s an important point to say that the only reason Donald Trump was even able to start casting this doubt is that we have this discriminatory provision, which ultimately is the real problem. What I like about your book is that you accept the legitimacy of the pessimist perspective. You call for a deeply empathetic understanding of its sources, and for actually looking at the facts that have given rise to it, actually confronting the history of racism and its continuation today. But you also say you classify yourself as an optimist. You do have an essay in here, called, “The Civil Rights Act did make a difference!” And in that essay, you recount being born in the Jim Crow South. And you recount what that actually meant in practice, which is that when you went on family trips, you had to load up all the food beforehand so that you didn’t have to stop at motels and restaurants. And then there are real obvious things where the law actually managed to change within your lifetime.

Kennedy

Yes. I was born in 1954, which is the same year as Brown v. Board of Education, which was the case in which the Supreme Court of the United States invalidated racial segregation in public primary and secondary schooling. Over the course of my lifetime, I have seen considerable change. Not only have I seen considerable change, but I have been the beneficiary of those changes. I have lived a very privileged life. And in my thinking about race, I think it’s important to remind myself of the way in which I have lived a privileged life, and I have tried to make sure that that privilege does not obscure my vision of some of the ways in which oppression is still very much a part of American life. I went to a fancy secondary school—St. Albans School for Boys. A wonderful school, a fancy private school. I went to Princeton University for college. I went to Oxford. I went to Yale Law School. I’ve been teaching for over 30 years at Harvard Law School. I’ve lived a very privileged existence. And that privilege was in part a consequence of the struggles waged by people like Derrick Bell. And I have to remember that. I want to remember that. I want to honor that. Now, is racism still a tremendous scandal in American life? Yes, it is. Take a look at any indicator of well- being in America—life expectancy, infant mortality, incarceration, risk of being a victim of crime—and we see a clear racial hierarchy. And if you’re dark-skinned, your risk for these bad things happening goes way up. That’s the way it is in America. And it’s absolutely scandalous. We have not done nearly enough about it. And so I want to be attentive to that. I also, however, want to be attentive to another tradition in American life, the antiracist tradition. Yes, we need to remember John C. Calhoun, who believed that slavery was a positive good. Yep, we need to be attentive to John C. Calhoun. But we also need to be attentive to William Lloyd Garrison, the great abolitionist. We also need to be attentive to the people who founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). By the way, the founders were mainly white. We need to be attentive to the antiracist of every complexion, including white people who were willing to give their lives for the struggle to overcome racial oppression. We live in a complicated world, and all I say to folks is, let’s embrace the complications.

Robinson

You have a passage in here critiquing the race blindness perspective, or colorblindness. This is the take on the right which asks, Why are we still talking about race? The problem is that we’re talking about it, not that there’s any actual real-life discrimination. We equalized the laws. We got racial language out of the laws in the 1960s. So anything since then is clearly something that Black people just need to work on within their culture. You say the fact that African Americans face a much greater risk than European Americans and suffer from a range of social catastrophes—unemployment, malnourishment, poverty, incarceration, eviction, vulnerability to infectious diseases—is not accidental. It’s the consequence of indefensible present or past discrimination based on race and unworthy of support is any vision of the racial promised land that accommodates complacently such pervasive harm stemming from racial wrongs. And I like that. I identify as my central problem with those on the right (in talking about race) a complacent accommodation of inequalities that I find repugnant. People on the right are just fine with it or find rationalizations for it. They find ways to shift the blame and avoid thinking seriously about what our responsibility is to continue the work of that first and second Reconstruction.

Kennedy

I agree completely with you. Unfortunately, I think it’s worse than what you just portrayed. There is the problem of complacency. And, of course, complacency is a big problem, as is accommodating the legacy of racial oppression. But what has crept into more prominence in American life recently is not mere complacency but actual racial hostility. The people who stormed the Capitol on January 6, 2021 with Confederate flags weren’t simply being complacent. Their flag was an emblem that was suggesting something else. It wasn’t just: you guys need to be quiet and just get on with things. No. It was: let’s make America great again. Let’s take back our country again. Let’s go back to the good old days. Well, the good old days were the days before 1860, the good old days of segregation. That’s the problem in America right now. It’s not mere complacency. Complacency can be deadly. I don’t want to go light on complacency. But the terrible thing is that we’ve got things that are even worse than complacency. And, in fact, we are facing sentiments that I actually thought had been consigned to the past. I really did. I’ve written in various places that no politician with national ambitions would dare use certain language, use certain tropes, use certain images, deploy certain ideas that could plausibly be viewed as just nakedly racist. I have written that. Well, guess what? I was clearly wrong. Clearly. We now have a situation in the United States of America in which one of the major parties clearly does not mind accommodating people who are actively and openly hostile to notions of racial justice. That is the serious plight of America. And it’s not simply something that is a threat to racial minorities, though it is a threat to racial minorities. It has become a threat to American democracy itself. And that is something that is new in my life. I was a teenager in 1968. Now remember, in 1968 we had the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, and rioting in the streets. 1968 is a year full of disruption. There was a presidential election that year. For all that was going on, no one was seriously concerned about the transfer of power. No one was concerned about the prospect of a coup. That was not on anybody’s mind. There was nobody writing serious editorials asking, What is the military going to do? There was nothing like that. In the last couple of years in the United States of America, there has been such talk and for good reason. These are the things that were once a threat to democracy in terms of Black Americans participating in American democracy. They have now been more generalized. And the problem is a general problem. That’s what we face.

Robinson

It is notable that under Trump there was a shift among pretty mainstream Republicans to the position that you should essentially never accept the outcome of an election that you lose as being legitimate. What that means is that it’s acceptable to try to cling to power by any means necessary. And what we see is the ramping up of efforts to disenfranchise people all across the country, like gerrymandering. You write a lot about the Supreme Court in this book. You are very blunt in saying that we need to acknowledge that the Supreme Court Justices are, in fact, politicians in robes. There are, in fact, Republican Justices and Democratic Justices. It is an illusion that the court is composed of people who are dispassionate legal analysts. A lot of people don’t believe this, but for some reason, a lot of law professors still seem to try to maintain this distinction. In practice, that means that the court has the power, essentially, to veto popular legislation, to overturn parts of the Voting Rights Act as it sees fit, and the court is now under the control of a right-wing faction. A core mechanism for guaranteeing the preservation of those democratic rights has disappeared or at least eroded.

Kennedy

Absolutely. The fact of the matter is, we have a reactionary Supreme Court. Sometimes I listen to newscasters and commentators, and they’ll talk about how the court has recently become conservative. The court has not recently become conservative. We’ve had a conservative Supreme Court since the early 1970s. What we have now is a right-wing, absolutely reactionary, Supreme Court. Let’s say you are a unionist and you take your legal complaint to the Supreme Court of the United States. Well, first of all, if you’re a unionist, you don’t want to take your case to the Supreme Court of the United States. A good unionist lawyer is going to try to keep his or her case away from the Supreme Court. And the same goes for a person that is fighting on behalf of women’s rights. If you’re a person who’s fighting on behalf of the rights of racial minorities, the last place you want to go is the Supreme Court of the United States. That’s the way it is, and that’s how it’s going to be for the foreseeable future. And you’re right. I’ve got a number of essays in the book in which I propound what I think is a realistic view of the Supreme Court. You don’t have to come at it with fancy theories. Just be realistic. And understand what the Supreme Court does, and how the Supreme Court is stocked. It’s really too bad. And you’re right to fault the law schools. The way in which people even talk about the Supreme Court is to give it this kind of meritocratic gloss, which would lead many people to think, well, the most esteemed jurists are the people who ascend to the Supreme Court of the United States. No, not true at all. Every now and then, you get a person on the Supreme Court who is an esteemed jurist. Every once in a while that happens. And in fact, when it happens, it’s talked about, because it doesn’t happen that often. The people who are on the Supreme Court are typically good lawyers. I didn’t say great lawyers. I said they’re good lawyers who I’m sure are politically connected. They are people who have come to the attention of a president and the president—for various political reasons—nominates them, and then they get enough support to be confirmed by the Senate. Now, in the law school world, once a person gets on the Supreme Court, they don’t have thoughts anymore. When they were regular folk, they had thoughts about the law. But once they get on the Supreme Court, they have a capital J, Jurisprudence. And then they go to the law schools and they’re treated as if they were philosopher kings or philosopher queens. It’s ridiculous. And in my book, I poke fun at that. And there’s a serious reason to poke fun at it because, actually, I think that the American public is really quite deeply misinformed about the function of the Supreme Court. They’re misinformed about the Justices. They’re misinformed about what the Supreme Court actually does. So what we have in America now is the following. The federal government has three big branches: the executive branch, the legislative branch, and the judicial branch. The judicial branch is firmly in the grip of a right-wing faction. And it’s going to be that way for a while. And in terms of American politics, that has to be considered very seriously.

Robinson

It’s consistently a source of frustration to me when I see people who should know better push the philosopher king view. When Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett were nominated, you saw some op-eds from liberal law professors saying, I am a liberal, but this isn’t about politics. They’re extremely competent and knowledgeable people. So there’s no reason to oppose them going to the Supreme Court. You point out that Justice Scalia was overwhelmingly confirmed because his intellect was respected. But we have to understand that oftentimes, people’s constitutional theories are derived from or built on their political ideologies. In the book, you’re scathing about Clarence Thomas. We interviewed Corey Robin about his Clarence Thomas book, and he situates Clarence Thomas in that pessimistic tradition and tries to give him a kind of intellectual credit, but you actually say that Robin has been hoodwinked by a con man, essentially, because Clarence Thomas is a right-wing political ideologue who advances right-wing political positions, and we need to understand that. When we don’t understand this, when only Donald Trump understands that the court is political and says, I’m going to get some Trump Justices on, I want some Trump judges, and when we buy into the bs of John Roberts who says, No, judges are umpires who call balls and strikes, then we get things like—and I wrote an article on this—Ruth Bader Ginsburg not retiring. And you say that Ginsburg not retiring was one of the most selfish acts by a public figure in recent memory. And I agree, but I think what is interesting about the reason that she didn’t retire is that she seems to have accepted the belief that if she retired, it would be an admission that the court was political, and she and Justice Breyer are so committed to this view, and they don’t like this grubby view of judges as being partisans. They don’t want to acknowledge through their retirement that this is, in fact—in some ways—a power struggle.

Kennedy

Just a few days ago, there was an argument about a law in Mississippi basically getting rid of a woman’s right to an abortion, or at least getting rid of the right as that right has been framed by Roe v. Wade. There was an argument. You listen to that argument. Justice Thomas asked several questions. And he asked these questions as if he’s seriously groping for an answer. Um, please. Cut the pretense. We all know what his view is. He has shown his view over the past 30 years. And he will show his view before the year is out. This idea that he comes to this issue with an open mind, and that he’s going to listen to these arguments, or take in the facts, these contending views, and then make up his mind—he’s trading on a naive view. And, unfortunately, that naive view is all too popular. You mentioned Chief Justice Roberts and his idea that the judges are not the players, the judges are the umpires. It’s not just Roberts who says things like that—ridiculous things like that. Quite literally, that warrants ridicule. The Justice who has come out with this ridiculous view, most recently, is not a conservative. The person who has come out with this most recently is the senior liberal judge on the Supreme Court. Justice Breyer talks about, quote unquote, the perils of politics, and says that he doesn’t know of judges who actually impose their politics in their judging. Well, I mean, where have you been? And furthermore, you’re right when you point out that he has suggested that one reason why he doesn’t want to retire is that it would suggest that it’s a political decision. Well, frankly, we saw Justice Ginsburg and her failure to be a responsible progressive, a liberal—whatever label you want. Here is a person who did a lot of good things in her career as a jurist. A lot of good things. Yet because of her unwillingness to retire, Barack Obama wasn’t able to put on the court someone who would have continued her way of thinking about the United States Constitution. What happened? It was completely foreseeable. There were people who were begging her to retire, and she did not. So she dies in office and gives Donald Trump the ability to appoint someone to replace her. Well, we are going to see over the coming months—the coming years, maybe the coming decades—the person who will contribute to attacking the things that Ruth Bader Ginsburg cared about the most. That’s very sad. And I hope that we don’t see that with Justice Breyer. But we might. And it seems to me that people ought to be very critical of Justice Breyer, and his naive view. It’s hard. In fact, it’s worse than naive because he’s a smart person. He’s been around the block a few times. I don’t take that seriously. I don’t think that it is mere naivete. I think that he is actually more thoughtful than what appears in his book. And that suggests to me something that is actually worse than naivete. I think that he is selling a naive view of the Supreme Court and willfully trying to pull the wool over the eyes of the public. And to that extent, he, in my view, is selling a mendacious view of the Supreme Court. So I’m upping the ante, actually, in my critique.

Robinson

Yeah. Everyone wants to present themselves as a wise philosopher king whose judgments have nothing to do with political values. One of the things about following Supreme Court decisions closely is that one might miss the fact that there’s a reason that politics are inherent to the Supreme Court. It’s not just that these people are fallible, or they’re corrupted by their political ideas, or that they could be neutral and they’re just not. It’s that the decisions that the Supreme Court is called upon to make require making these value judgments.

Kennedy

Absolutely.

Robinson

And these value judgments are necessarily influenced by your political inclinations—the relative weight that you give to the right of someone to eat at a lunch counter versus the right of a property owner to exclude someone, the relative weight that you give to the right of the fetus to the right of the mother. These things that seemed like constitutional judgments are necessarily built on things that are political to their core.

Kennedy

Absolutely. Due process, equal protection of the law—when you are weighing things, you have these controversies. They are disputes. They are contests. One person has a story, and oftentimes actually has a reasonable story. And then you have another person and they have a reasonable story. They both cite cases; they both have an argument. The question is, who’s going to prevail? And that is going to be a matter of political judgment, moral judgment, and intuition. What is your view about the state purposefully executing someone? What’s your view about that? There’s a lot that’s going to go into that: moral intuition, religious inclinations, and personal experience. I worked for a great man, Thurgood Marshall. He thought that the death penalty should just be outlawed entirely. He thought that never, ever should the government execute someone. Well, where did that come from? He could talk about the history of the 8th Amendment. He could talk about the history of the 14th amendment. He could talk about a lot of things. But certainly one thing that influenced him was that he himself represented people who were put to death and who were innocent. That had something to do with his ultimate calculation. And you’re absolutely right—and this is a good point. It’s not that some people are corrupted by politics. It’s not that some people descend into politics while they’re judges. They are necessarily political. You cannot be apolitical and do your work as a Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States, or, frankly, the work of any other judge. What I’m saying doesn’t just go for Justices. It doesn’t just go for judges on the United States Court of Appeals. It doesn’t just go for district court judges. It goes for all judges.

Robinson

You have an essay “Remembering Thurgood Marshall” in this book. What I like about the book is that you’re never not critical of any figure you profile, from Derrick Bell to Black nationalists to Thurgood Marshall. But you make a strong case for his quality as a jurist. Oftentimes, he was subjected to a number of unfair charges that essentially say, Oh, well, you bring politics into the court because you have these other things that you care about, unlike these other Justices. But you’re the one who’s a racial Justice, which kind of contaminates the pristine world of legal logic that otherwise would be apolitical. And it’s just not the case.

Kennedy

Thurgood Marshall was one of the great lawyers in the history of the world. I really enjoyed writing that essay about Thurgood Marshall. One of the reasons why I enjoyed it is because of course, it made me reminisce a bit when I worked for him in the 1983-84 Supreme Court term. And the cool thing about Thurgood Marshall is that many people who become Justices of the Supreme Court are remembered because they were Justices. A president nominated them, the Senate confirmed them, they were put on the court, and they made these important decisions. That’s their basic claim to fame. Not so with Thurgood Marshall. If Thurgood Marshall had not gone on the Supreme Court of the United States—if he had not—he would still be worthy of a big chapter in the history of American law. He would still be a more significant jurist than most people who have been Justices of the Supreme Court. He was an absolutely extraordinary person. And people have not given him his due. Now, you’re right. Am I critical of Thurgood Marshall in certain ways? Yeah. But frankly, I think that one ought to be critical of everyone and everything. I don’t think that you can actually take the measure of someone suitably without having a critical approach to them. After all, if you’re talking about John Stuart Mill, if you’re talking about John Rawls, if you’re talking about Nietzsche, if you’re talking about Machiavelli or Hobbes, people have a critical view of these people. They were remarkable thinkers, but you still have a critical view of them. And so I want to take thinkers—including Black thinkers—seriously. And in order to do that, it seems to me that one has to have a critical, skeptical view.

Robinson

I want to finish by asking about Derrick Bell. You have a long essay about Derrick Bell in the book. Derrick Bell, for people who don’t know, was the Harvard law professor who was the co-founder of critical race theory as it originally was propounded. You have a fascinating history of your relationship with the late Professor Bell. He certainly had some disparaging words for you at some point. He was definitely in that racial pessimist camp in that he basically thought that Brown v. Board of Education was almost worse than nothing. He thought that there would never be any kind of racial equality—not only in his lifetime, but ever—in the United States. And you were highly, highly critical of his work at your time. But you seem to have over time developed a kind of appreciation for him. The essay is a kind of encouragement to people to take his work and his life seriously even if they don’t agree with all of his conclusions.

Kennedy

Yes. That essay was very meaningful to me. I felt that during his lifetime, I had not given him his due. I knew him; we were friendly. We also crossed swords at various points. But I don’t think that I had given him his due and in this essay—which still has criticism in it—I wanted to point out to readers what a remarkable person he was. I wanted to point out the difficulties that he faced. He was senior to me. He was very helpful to me in my career. Even when he was critical of me, he was helpful to me. And as I’ve gotten older and looked back—as I was writing this and doing research for it—I was thinking to myself, what was it like to be the only Black professor at Harvard Law School in 1970? He had a different profile. He did not go to Harvard Law School. He did not go to Yale Law School. He did not go to Columbia Law School. He went to the University of Pittsburgh Law School. He did not have a fancy clerkship. He had worked in the Department of Justice. He had worked for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. He had a very different profile. He was looked down upon when he came to Harvard Law School. And he had to face that, and he had to overcome that. And he had to do work in an unwelcoming environment. And he did. He was a good teacher. He was a productive and insightful scholar. And I think that when he was alive, I didn’t see fully enough what he had faced and what he had overcome and what he had contributed. And in this piece, I tried to give him his due. And that’s why that piece meant and means so much to me.

Robinson

There’s also something remarkable about the fact of being looked down upon by a lot of his colleagues who see him as having the burden of proof to justify his presence there. He did not take the route of saying, Well, okay, I’m going to conform. Now that I’m at Harvard Law School, I’m going to embody the ideal of the Harvard law professor according to the standards of the institution. Instead, he took on the institution to the point of being ousted from the institution, and that takes a remarkable independence of character, the kind of aggressiveness with which he fought for the hiring of professors of color was not something that everyone who ascended to that position from his background would necessarily have done.

Kennedy

Absolutely. He gave an ultimatum to Harvard University. Now, the great irony is—you know this from my essay that I don’t agree fully with his judgment about what the Harvard University faculty was about—but I’ve got to salute a person who gives an ultimatum to Harvard University. And then when Harvard University didn’t meet the ultimatum, he walked. And not only that. In his scholarly life, he also showed tremendous independence. He was willing to go his own way. He was willing to write things in a fashion that had other people and me scratching our heads. He was independent. And again—I say this as a person who was critical of him, and who remains critical in important ways—even in the teeth of his disagreement with me, he still saw it as his responsibility, his duty, and his obligation to extend the borders of opportunity for people who had historically been marginalized, and that included people of color, that especially included women of color and women generally. And so Derrick Bell was an activist-scholar who looked behind him and was absolutely committed to pushing open the gates of opportunity. And for that, it seems to me, he is worthy of a salute. And he is worthy of our gratitude.

Robinson

It’s one of the most moving essays in the book because it’s very personal. Not every professor would dare to write science fiction stories because they think it would lower their standing among their colleagues. And I was baffled by some of his fiction when I first read it when I was assigned it as an undergraduate. It took years for me to appreciate his story of the space traders, which is about the United States voting to trade its Black population to aliens in exchange for vast riches. And I finally realized that this was a story not predicting what the United States would do, but that encouraged us to think about what we already had been willing to accept, and what horrible moral compromises this country’s white population would make, how much it would be willing to devalue the lives of others for the sake of enriching itself as it had over the course of its history. And after some years, I came to think that this was an incredibly challenging and profound story that I wanted everyone to read. But it took years to appreciate that.

Kennedy

During the COVID pandemic, how many times have I heard people in conversations bring up that very essay that you’re talking about? I have heard people of varying ideological persuasions say that the discussion going on about how the United States is dealing with this health crisis, puts me in mind of the piece that Derrick Bell wrote, and I said, You know what? You’re right. Ah, maybe I should go reread. Well, he wrote that a long time ago. Again, I’m critical of Derrick Bell in certain ways. But one thing I’ve got to say is that Derrick Bell would not have been caught unawares about the ascendancy of Donald Trump. He would not have been one of those people with eyes bulging and hands wringing, saying, Oh my gosh, where did this come from? He would have been prepared for this. And he would have actually helped prepare our society for the prospect of this happening. So Derrick Bell had some real insights to offer and his work bears reading and rereading.

Robinson

The critical race theorists have, in many ways, a more realistic perspective on American society than the race blindness people do. Well, Professor Randall Kennedy, thank you so much for this fascinating conversation. I really enjoyed it. People should pick up the book Say it Loud!: On Race, Law, History and Culture available now from Pantheon books. We couldn’t get into all of the essays because it collects a number of your pieces on many, many different topics over the past few years. Thank you so much.

Kennedy

I really appreciate it. Thank you for having me on. Keep on pushing.