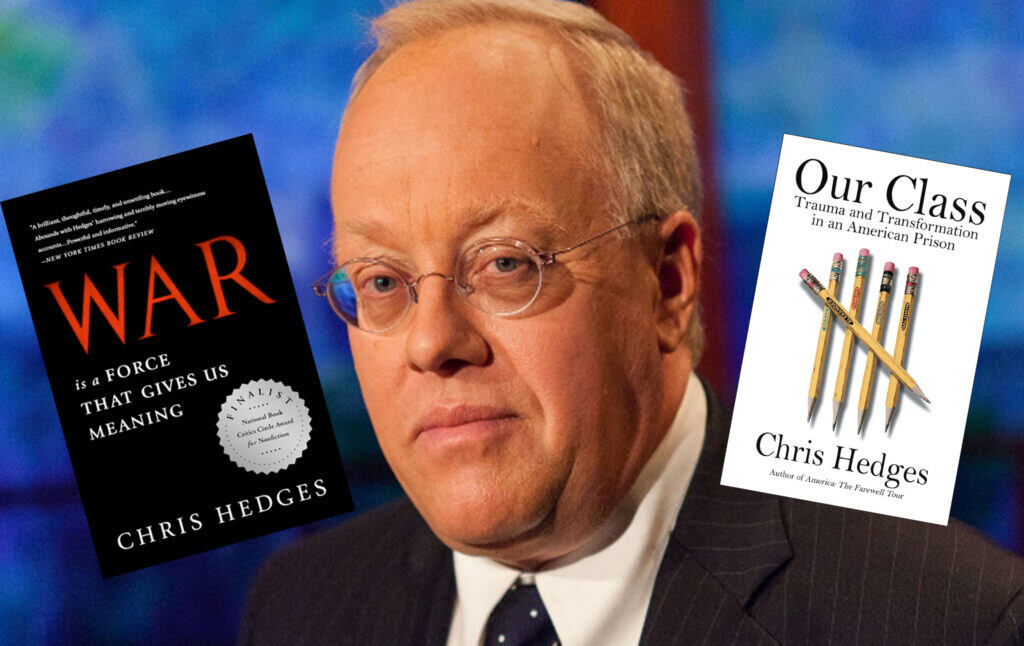

Chris Hedges on the Inhumanity of Wars and Prisons

Former war correspondent Chris Hedges discusses what war zones and prisons have in common: They’re the places where America hides victims of white supremacy.

Chris Hedges worked for many years as a war correspondent for the New York Times. He left the paper, in part, because of a difference of opinion over war. Hedges has spent his career writing about places Americans would prefer not to think about—the battlefields where the victims of our wars die, and the prisons where we discard and warehouse our fellow citizens. He has taught for many years in a New Jersey State Prison and other prisons. Teaching in prisons was the subject of his latest book, Our Class: Trauma and Transformation in an American Prison, available from Simon and Schuster. His other books include War is A Force That Gives Us Meaning, American Fascists: The Christian Right and the War on America, and The World As It Is. Hedges recently joined editor in chief Nathan J. Robinson on the Current Affairs podcast. This interview has been lightly condensed and edited for grammar and clarity.

Robinson

You’ve written several books. You’ve reported from many different places. A theme in your writing is to focus on some of the darker truths about the world and about the country that we live in and to face those truths squarely—whether it’s war, or, in the case of your new book, the prison system. One New York Times review of a book of yours read: “fire and brimstone preacher who preaches the damnation of America.” I don’t think that’s particularly fair. There is a lot we prefer not to look at, and you force us to look at those things. In your latest book, what is it that you want to open our eyes to?

Hedges

I suppose, at its core, the evil of white supremacy. I spent 20 years overseas on the outer reaches of the empire. The viciousness of empire is the external expression of white supremacy. And that internal expression of white supremacy, as you correctly pointed out, is masked, hidden in the same way that the crimes of empire are hidden. So there is a kind of continuity to my work. And it’s fed by the same understanding of the evils of the poison of nationalism, of self-exaltation, and of ignorance, which, as James Baldwin points out, many white Americans confuse for innocence. So yes, I would say that you’re right that that is probably the core characteristic of my reporting. I volunteered to go into places like Sarajevo. I remember when I told the executive editor of the New York Times—I was currently the Middle East Bureau Chief for the New York Times—that I wanted to cover the war in the former Yugoslavia, which meant going to Sarajevo when it was being shelled with hundreds of artillery pieces and 90 millimeter tank rounds and Katyusha rockets. Constant sniper fire, he said. The line starts and ends with you. I knew he was happy I went but it wasn’t a huge selection process. So I purposely put myself in those kinds of places to expose this reality which both the empire externally and the empire internally work so hard to hide. That’s right.

Robinson

You write that we tell ourselves stories about war, of our own goodness and the justice of our cause. But beneath the surface is horrific violence against human beings, people that we don’t see as human beings. In the case of the prison system, something rather similar is going on. We think of ourselves as being in a war against crime, and stopping a class of people who are the criminal class. But when you actually go beneath the stories that we tell ourselves, you see, once again, a set of human beings, the human beings you write about in your book that are full, three-dimensional people who are the victims of those who tell themselves the stories.

Hedges

It’s a process of dehumanization, both in terms of war, and in terms of relegating people—mostly poor people of color—to this criminal caste system. Of course, when they’re released, all of the impediments and barriers that are placed in front of people who get out of prison make it almost impossible for them to reenter the society in any meaningful way. Often, they can’t get employment. Because of their record, they are denied public assistance, public housing. Basically any job that requires a license—even hairdressing—you can’t get if you have a felony record. And then if they’re arrested again, especially when they’re on probation, they can be tossed back in prison for very trivial offenses. And that’s why we have within five years, a 76% recidivism rate. The size of our prison population is not accidental. We have 25% of the world’s prison population yet we’re less than 5% of the world’s population itself. Ninety-four percent of those in prison never got a jury trial. They were coerced—and I don’t use that word lightly. That’s what happens. They were coerced into taking a plea deal. And one of the dark ironies is that the students that I teach in the prison with the longest prison sentences are the ones who went to trial. And they usually went to trial because they didn’t commit the crime. But you stack all sorts of charges—the police and the prosecutors know that many of the charges are bogus, they didn’t actually commit them—but then you use them as bargaining chips. Kidnapping is a big one they’ll put you on because that’s 25 years. I spent a lot of time in places like Gaza. You see the demonization of Muslims, the same kind of demonization of poor people of color. And just one other point: there is a kind of dark logic to the carceral state that we have created. Under neoliberalism and deindustrialization, you’ve turned these urban enclaves into wastelands, places like Camden and Detroit and everywhere else. And you’ve ruptured—this is what Émile Durkheim writes about—these social bonds that knit you into a society: work, a sense of place, a sense of meaning, a sense of stability, a sense of worth. All of these are broken. And so with the rupturing of those social bonds, you create militarized police—in essence, internal armies of occupation—and a massive prison system as the primary forms of social control. So it’s not accidental that police have been militarized. And it’s not accidental that we have 25% of the world’s prison population. This is how the state has reacted to stripping a segment of the population of any place within the society, what Marx called surplus labor, and kind of casting them aside as human refuse.

Robinson

The dark irony that you noted about the innocent is the trial penalty. If you go to trial and are found guilty, you get a much longer sentence than if you take a plea deal. If you consider the person who is innocent to be the most likely to insist upon a trial, then they’re the ones who get that horrible penalty. You have these people who have, in fact, committed the crimes getting out, and you, the innocent person who insisted on the truth, are punished for it. You had someone in one of your classes who wrote “I am innocent” every time on the assignment when they turned it in, because they were so firmly insistent on this truth that no one would acknowledge. But we also need to understand that people—even those who did commit crimes—are still human beings. They’re often complicated human beings. They often have a mixture of good and bad qualities. You say in the book that in all your time teaching in prisons, you’ve met maybe a couple of people you could classify as genuine psychopaths, and everyone else is a multi-dimensional human being.

Hedges

Well, even psychopaths are multi-dimensional.

Robinson

That’s true.

Hedges

But yeah, they’re quite complex. The ones I’ve often taught are brilliant. Creepy, but brilliant. When you live in that culture—again, I spent 20 years in war around a lot of violence. There’s a story I relayed in the book. I helped students write a play that was eventually put on by a theater in Trenton and then eventually published. That is the conceit of the book—the process of writing that play. The students write about their own lives, it exposes what they’ve been through and what their families have been through, both inside and outside prison. But in the course of that, there’s a prison code. And again, the code is honored more in the breach than the observance. That’s kind of interesting. And as they’re writing the play, a guy comes into the prison for the murder of the brother of one of the people in the prison, and the code says, You have to kill them. And when we were working on that scene, I said to the class, Well, if you shank someone—a shank is a homemade knife—in prison, don’t they know they’re going to get another life bid, that it means they’ll never leave? And the whole class—most of the class—said, Oh, yes, they know. But it doesn’t matter. It’s the code, you have to. At the end of the class, one of the students stopped me and said, You know, I shanked someone in a youth correctional facility—Wagner, where I used to teach—and I killed him. I didn’t think about any of that. I was so enraged that I was just overpowered by my rage. And the next class, one of the students—another student who’d seen that interaction between me and the person who had shanked someone in the prison—came up and said, You know, it was interesting, I watched your face, and you didn’t register or react. And I said, Well, because I’ve spent my life around people who kill for a living. And all of you here are amateurs. Many of these people are in it because they come out of violent environments. They employ violence. It’s interesting: Within the prison, there’s real segregation. The two groups that get segregated are pedophiles and rapists. But also people who kill with their hands. That’s not something that I wouldn’t have necessarily known if I hadn’t worked in the prison. Touching the body—you know, either in the case of killing them, or afterward—is considered really creepy. And you’re kind of pushed out of the prison society. Most of the people have high-powered weapons, especially if they’re dealing drugs, and it’s not to shoot at the police. It’s because there’s a whole subset within those communities that prey on drug dealers because they have money and they have drugs. I was explaining to some of my students about being in firefights when I covered the war in El Salvador, with Salvadoran soldiers who really didn’t want to get killed. And they would just take their M16 up over their heads and spray it everywhere and somebody said, Oh, yeah, well, that’s just like a drive-by. I often teach in a maximum security prison. So a pretty significant segment of my students are in there for murder. But they’re not murderers. They’re not killers. There are killers—I’m not romantic about it, I’ve taught some of them, and you don’t want them walking the streets—but with that you usually have a mental health issue. But it’s more the environment in which they have easy access to weapons and everyone has weapons. So I think you’re right. It’s good that you brought that up. I’ve been teaching there for so long, many of my students are getting out. Several of them are working as community organizers. They graduated summa cum laude from Rutgers. But yes, they committed the crime. That’s the other interesting thing about being in prison. I don’t really have any power to impact whether they’re going to get an appeal or anything. I found people are quite up front. The people who tell me they didn’t commit the crime usually didn’t commit the crime. And the ones who did commit the crime are trying to process that—it’s usually in an altercation. It’s usually a fight. It’s a robbery that went wrong. Not to explain it away. But they’re consumed by the very negative passions of the moment, but are they actually killers? I would say the number of people I would consider killers in a prison is surprisingly small.

Robinson

Hmm. People might be surprised at first by the distinction between those that kill with their hands or handle the body and those who shoot somebody. But it does make sense—a hierarchy among murderers. There is a big difference between someone who is kind of sadistic, and someone who is a normal human being who gets into a fight that gets out of control or lets their emotions get the better of them. One of the things you’ve also pointed out many times from your experience with war is that it is conducted by ordinary people, that killers are people like us. Those of us who think we don’t have the capacity to do the deeds that we think are done by a class of “evil people”—we’re deluding ourselves. There is a darkness within normal human beings. When I first went into a maximum security prison, it really shocked me how similar to myself everyone I met was. There are cultural barriers, but as you get to know people, it’s very, very eerie, actually.

Hedges

Well, that’s what you find out in war. The line between victim and victimizer is razor thin. Most of us can be conditioned to do things that are wrong and evil. When you send people to basic training, they use operant conditioning the same way you train a dog through repetitive motion simulating a battlefield experience to teach people to kill. Christopher Browning’s book Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland does a really amazing job of explaining this. He looks at a police battalion. These weren’t Nazis. These men were usually in their 40s. They had families with children. And they were conscripted to go off to Poland and carry out wholesale massacres, mostly of Jews. And there was actually no punishment. They had no serious punishment for people who refused. But only a handful in the battalion, I think three or four, wouldn’t do it. And it’s what you learn in war. I’ll just give one story. So when I went to Harvard Divinity School, I lived in Roxbury and ran a small church there. And so I would commute to Cambridge to take my classes, and then I was back in the ghetto at night. And that’s an experience that will really teach you to hate Harvard liberals.

Robinson

Yeah. I didn’t have that experience. But I still came to the same conclusion.

Hedges

All those people who talk about empowering people they’ve never met. I was also a member of the Greater Boston YMCA boxing team. And I was living in a manse next to a church. It was very rundown in fact—the street in back of the manse had the most homicides of any street in the city of Boston. And there was one old air-conditioning unit. So in the summer, I would actually move my mattress down to the first floor and sleep on the floor. And there was a small alley between the church and the manse. And one night I heard screaming, and I ran outside. And I knew them. It was two heroin addicts who were attempting to rape a 14-year-old girl. I also knew they had knives. And I had to incapacitate them as swiftly as I could. And this isn’t bravado because heroin addicts are just skin and bones. There’s nothing to them. But I was throwing them against the brick wall. I was throwing them onto the sidewalk. And I was just trying to neutralize them so I could get the girl away from them. But I could have killed them. And one of my students who I love very much had just gotten out of the Marine Corps. He is a huge guy. And somebody took his girlfriend, offered his girlfriend a line of coke at a bar, took her to the bathroom, locked the door, and tried to rape her. She came out and he killed the man in a fight. And I thought, you know, I could have easily been that person at that moment. So yes, I think you’re exactly right. By the way, the Greeks, in Philoctetes and these kinds of plays, talk about putting yourself within the circle of suffering so that the contagion of suffering becomes part of your persona so that you begin to see yourself in the person (in this case Philoctetes) who’s suffering. That’s a good point you raise. That’s exactly what happens in a prison. It is a kind of “oh my God” moment. The difference between me and my students is often negligible and in some cases nonexistent.

Robinson

Here in New Orleans, we have the National World War II Museum. I’m writing about the way that America remembers World War II as the good war. It’s basically the Museum of American Greatness, about how we kicked Japan’s ass. When you actually go in, and you read about the war from the Japanese and German perspective, and you actually see the pictures of the ruined cities, and you see what actually happened in the war, your ability to conceive of it as a just war erodes. But it’s the most extreme example of what happens when you start thinking of the world in terms of your abstract ideas, and you’re just totally taken away from the actual sights and sounds and smells of human suffering. You mention how liberals don’t like the smell of poverty, or that they care about it in the abstract. The real experience of war is about the smell of death, which is one thing that you won’t get in the museum. There’s the visceral experience of real human suffering that we keep away from us so carefully through so many different mechanisms.

Hedges

Well, that’s war. The images—especially the Hollywood images that present war—are kind of the same as pornography. It’s pornography and violence. So you’re right. All of the actual forces that overpower you in the middle of combat—not just smell, but noise, and fear—and you will do things … Anyone who has spent long enough as I have in war, will do things out of fear that they’re ashamed of. And I write in my first book about being in Sudan with a very close friend of mine, Tony Horwitz, who was working for the Wall Street Journal. He went on to become a very good writer. And there was a coup or an attempted coup. And we were trying to get back before the curfew. And we walked down the wrong street toward the presidential palace. It was already dusk, and I heard the soldiers flick the safeties off their automatic weapons, and Tony was a couple of paces in front of me. He died. I unthinkingly stepped right in back of him so that the bullets would go through him first. You know, courage is not a constant. And so all of the actual sights, sounds, and emotions, including the adrenaline rushes of war—it’s hallucinogenic in the sense of what huge shells do to human bodies (I saw this in Sarajevo), severing them in half. One almost can’t absorb it. Even now, years later, I look back and I wonder, did I really see that? You question what you experienced because it’s so abnormal. You can perpetuate the myth of war very easily when you drain all of those realities from it. My uncle fought in the South Pacific; my father was a veteran in North Africa. Most of my uncles fought in the war. But I have one uncle in the South Pacific. They didn’t take any prisoners. I mean, it’s part of the reason why we don’t do a lot of films. We love to fight the Nazis. In Hollywood, they don’t do a lot of films about the South Pacific. They were wrenching out teeth for gold. I’m not going to excuse what the Japanese did—it was savage as well. But so was the U.S. Marine Corps.

Robinson

It was a mutual dissent into the moral abyss, right? Both sides committed horrible atrocities which fueled further atrocities.

Hedges

I would say that it was set up beforehand. So the Japanese propaganda machine was racist toward the Americans and the Americans were—you had Walt Disney cartoons of “slant-eyed Japs,” or whatever they called them. It was a whole different theater. But it was barbaric. We do have to look at the bombing of Dresden, which was a war crime. There’s just no way around it. Kurt Vonnegut has a great book, Slaughterhouse-Five.

Robinson

And every other city in Germany, by the way. We were willing to talk about Dresden, but it was Hamburg, Munich, and every city in Germany.

Hedges

Yeah, of course. And it was consciously done to displace and kill the civilian population. That was the goal. At the beginning of the war Churchill was kind of against that and then embraced it after a bomber bombed London. Churchill acknowledged that it was a war crime. So, yeah. Once you get on the ground, all those delineations that we use to define ourselves as, quote unquote, good people, break down.

Robinson

Paul Fussell wrote an excellent book, Wartime, which is all about the realities of combat and what happens to the human body and how the viciousness of what actually took place was concealed from the American public. He writes that the American public has not come into moral maturity yet because we don’t actually understand anything about how the world really works. And so to get back to the kind of less viscerally extreme case—but still the same phenomenon going on in the prison system—another thing is that human beings are kept out of sight. What happens is that people don’t necessarily realize just how horrific some of the conditions in American prisons are. I mean, they vary from place to place, but you describe some things in the book such as people being kept in solitary confinement, the toilets don’t flush, intentionally, and people are kept there with their own waste for days at a time. It’s just the most horrific condition you could imagine plunging a human being into, and keeping them there. And that’s going on all the time, every day, all around the country that we inhabit.

Hedges

Right, and to a certain segment of the population, not to you and me. But if you’re poor, and especially if you’re Black. It’s a common experience, probably to someone you know or someone in your family. One of my students—as an aside—gets out and graduates summa cum laude from Rutgers. The Rutgers program is a great program—NJ-STEP—if they have a 3.1 average, they can actually get out and matriculate to Rutgers. Some of them finish their degree in the prison, but they can actually go to the campus. So he’s sold a clandestine cell phone by a guard, there’s all sorts of corruption. That’s how drugs—or any kind of contraband—usually get into a prison. And he’s caught with it. And he’s sent into solitary confinement for a year for a cell phone, which has left lasting psychological scars. And he’s put in one of these cells where there is no toilet. It’s a hole in the wall. And the feces and urine is collected every few days. So the stench just permeates the entire cell. There are actually cells in the prison in Trenton, New Jersey, that were former horse stalls, but the prison is quite old. And again, they have no toilet, and there’s no running water. And after there’s an altercation or they’re attempting to investigate something that’s happened in the prison, they’ll move you to what they call “the hole” while you’re waiting for them to determine whether or not you’ve committed this infraction and you’ll go into solitary. And they will put you in what they call a dry cell, which means there’s no water. They will use sensory deprivation—constant light, constant cold, constant heat—to break you down. This is normal practice within American prisons. And in its cruder form—I did a story for the New York Times about the parish jail in New Orleans where the guards were organizing gladiatorial combat for the people in the jail. And jails are actually worse than prison. A lot of my students just want to get out of the county jail any way possible. There’s no education program. They’re locked in there 23-24 hours a day. Sometimes it’s kind of a relief to get into prison. This was in New Orleans. They were giving prisoners the garbage can lids and mop handles and making them attack each other in kind of battalions. Yeah. Savagery takes place within the prison system. 80,000 of our citizens, as I speak, are in solitary confinement. And, you know, six days is what my students say—after six days in solitary, you begin to go crazy. Many people break down, which is kind of the purpose. And then what they do is they drug you up. They give you psychotropic drugs, and you’re just a zombie. You sleep all day, your hands shake, you shuffle down the hall. We lock up 25% of the people because we don’t have a healthcare system that deals adequately with mental health issues for the poor. Twenty-five percent of people in the prison system have severe mental health issues. And they don’t get therapy or treatment. They’re re-traumatized and drugged up.

Robinson

The good thing is that in recent years—partially because of Michelle Alexander’s work [The New Jim Crow], which you mentioned in the book that you teach to your students—there’s been a great deal more attention to the problem of mass incarceration. But a lot of it is discussed in ways that are statistical or abstract. We use the term “solitary confinement,” we hear “mass incarceration,” and we hear the numbers on how many people America has locked away in its prisons. But the visceral, first-person reality of life in an American prison is hidden. One of the services that your book does—it really opens this institution up for inspection. You’ve got scenes in here that I’m never going to forget: the whole thing with the communication through the toilet bowl phone that you describe at some length. When you actually start hearing about what life is like and how ordinary people improvise under incredibly trying conditions of deprivation, you really begin to empathize more.

Hedges

Yeah. That’s why I wrote it. And I think there are some very good books on the carceral system. But you’re right. Michelle Alexander writes more about the law. Hers is a great book. But it’s more about the breakdown of the legal system and those who are railroaded into the prison system without getting any kind of adequate judicial representation. And then we also have to acknowledge that, courtesy of Bill Clinton and Joe Biden, sentences are disproportionate compared to anywhere else in the world. I always tell my students, Guess how many years Gavrilo Princip got for assassinating the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne and his wife, Sophie: 20. People are serving for life and they’ve never been charged with a violent crime. So the sentences themselves are so draconian. I have one student, a brilliant student. He was in for, I think, 26 years. He got out. Because we ‘ve just turned prisons into warehouses, inmates are not getting any training. The college programs were not funded by the state. They’re funded by donations from foundations. So he gets out, he has no vocational skills, his partner gets pregnant, they have a child that is born prematurely at 23 weeks. The baby’s on oxygen 24-hours a day. He doesn’t have any money, and he can’t pay the medical bills. And so he starts to sell drugs. And he’s picked up. I went up to Goshen, New York to sit through a sentencing. And he’s given two-and-a-half years, leaving the mother alone with the child. I met with his lawyer beforehand, and he said, Oh, well, I read that he was involved in a robbery. (He didn’t kill anyone. He was in a robbery.) I read that he was in prison in New Jersey. In New York State, he would have gotten three or four years. So it’s also this disparity. There’s no rhyme or reason to the sentences. And then, of course, you’ve got the three strikes you’re out laws. Kevin Sharp, who’s now Leonard Peltier’s lawyer, was a federal judge. He quit because he said, I’m sending people to prison and they shouldn’t go for life. We say the system doesn’t work. Unfortunately, the system works exactly as it is designed to work. And it’s now become a multi-billion dollar a year industry. Not because of private prisons—there are private prisons, ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] uses a lot of them—but because everything in the prison has become privatized. So the food service, Aramark (we have cases of food poisoning), Global Tel Link, the commissary—everything is designed to make money. It’s fleecing the most vulnerable, which is the people who are incarcerated and their families. I will just add that they’re all getting fined. They get thousands of dollars in fines when they receive a sentence, which they can’t pay off when they’re earning $20 a month. And so they get out owing fines. If they can’t get a job and pay it back, there will be a warrant out, and they’ll go back in.

Robinson

The most disturbing example from your book is that if you want to go to the funeral of a loved one, you have to pay for the cost of the guards to escort you there.

Hedges

Yeah, it’s overtime. So it’s hundreds of dollars; it can be $1,000 or more dollars. You get 15 minutes and you’re shackled. And you can’t be with any family. You’re only alone in the funeral parlor with a corpse for 15 minutes. That’s it. Then they haul you out. That’s why many of them don’t go. Suddenly they’re $1,000 or more in debt.

Robinson

The funeral of a parent or child…

Hedges

Well, it has to be immediate family. You can’t get out for anyone else.

Robinson

This is such pointless cruelty. It’s clearly poverty that keeps you from giving up that tiny little privilege of 15 minutes with someone who’s passed. You mentioned the fact that prisons have become warehouses. The Rutgers program that you described sounds very good. But the quality of the education system in prisons around the country is incredibly inconsistent. Some places provide almost nothing. And you and I talked over email briefly before about the fact that we both observed that there is extreme hostility among prison authorities to education programs. They throw in the way all kinds of unnecessary bureaucratic obstacles, a kind of apparent lack of desire for the prisoners who want to educate themselves to receive new skills or new knowledge.

Hedges

Yeah. That was especially true when we began. Some of the corrections officers could be pretty unpleasant. Like they were poking a stick at you. If you react, you’re treated, in many ways, like a prisoner. If you react, if you get angry at the guard, you’re out. You’ll never come back in. They put snitches in the class. I was a victim of that. It’s kind of ridiculous. So I had to go in and spend five hours with a Special Investigations Division being questioned, and it wasn’t even an adequate record of the kinds of things that I said, and they let me back in. But another great professor didn’t get back in. So these snitches have a vested interest in pleasing the authorities. They’ll distort anything that the professor says. In the supermax prison in Trenton, they won’t allow the college program at all, because one of the administrators told us they’re all going to die in here anyway, they don’t need an education program. I actually went in on my own, which I was doing before there was a college program, with the head of the History Department, Celia Chazelle, at The College of New Jersey. We were buying the books ourselves and teaching a semester-long course, the equivalent of a college course, for people who had their GED. It didn’t have any academic validity. We would come home and print out certificates on our computer if they completed the coursework, and it would go in their file. I was doing this in Trenton, and taught a few classes in there and then proposed another class, and the prison called back and said, Nobody wants to take your class. Well, I happened to find out from one of the social workers that they never posted it. They just didn’t want the headache of it. So, I would say it’s a little better now because in East Jersey State Prison where the book is set, you have 140 students in the college program. But there are about 2,000 people in the prison. There are hundreds that want to get into the program. And you can’t get in unless your disciplinary record is really clean. So, in fact, the program has created an environment where those who want to get into the program are rigorously screened, and have to obey the very military-like, draconian rules that the prison has in order to get in. That has reduced a lot of incidents within the prison. So it’s a little better now not because they love the program, but because of that residual effect. And then we should also add that most of the people who work in the prisons are vets who have spent a lot of time in Iraq and Afghanistan. They don’t have college degrees, and nobody’s offered them free college education. So there is a kind of understandable hostility on their part as to why do these people get it and nobody ever offered it to us?

Robinson

Well, this is a classic feature of American society: getting people to resent those who have slightly more advantages in a country where the working class as a whole is crushed. And your book opens people’s eyes to the things they don’t want to confront—many things that are very bleak. The book is also built around something very beautiful that you watched happen, built around the collective writing and performing of this play among the people in your class. In many ways, their full humanity comes out. They mine their souls for material. They come to love drama and understand and appreciate great works of art. There is something that is truly awe-inspiring about what you observed within this bleak, depressing, and unjust institution

Hedges

A classroom in a prison is sacred space. Prisoners are referred to in prison by their number, not by their name. And in there, they become people whose opinions and thoughts and dignity are all validated. But in this particular class, it was inadvertent, I didn’t plan it, because I stumbled into the project of writing a play, just by accident. They didn’t have much experience with drama. So I wanted them to write dramatic scenes. I had attracted some very fine writers in the prison. And when I saw the quality of the writing, that’s when this project began. You build emotional barriers in a prison. If you show vulnerability, there are predators in that environment that will prey on those expressions of pain or weakness or grief or anything else. But in the class, they were writing about their deepest experiences of loss and grief and suffering and loneliness and everything else. And so they would get up in the classroom and read the scene. For some of them, of course, it was so emotional they couldn’t. Sometimes their hands would shake. I had people fighting back tears. And those emotional walls just crumbled. And you could be in prison for decades and never tell even your own cellmate about your past. In a prison, they don’t even use their legal names; they all have nicknames. They all have prison names. And so that class became something very special and created a bond that has existed to this day between the people in that class and of course, myself—especially now, as my students begin to get out, and I write about it. I’m usually at the gate, with their parents, meeting them.

Robinson

That captures what was one of my frustrations, which is just a deep anger at seeing a kind of squandered potential and the destruction of intelligent, kind, interesting, curious people who are deprived of everything and an opportunity to flourish and contribute. It’s just a maddening destruction of human potential.

Hedges

Yeah. It’s not just they who are impoverished. It’s not just their families who are impoverished. We’re all impoverished. These are some of the most remarkable people I’ve ever met. Everything has been conspired against them. I don’t think that many of us could go through what they went through and become who they became. They turn their cells into libraries. They are, as Antonio Gramsci says, organic intellectuals. One of my students matriculated to Rutgers and graduated summa cum laude. He got the first Harry S. Truman Fellowship of any student at Rutgers in over a decade. He goes to the University of Cambridge in England, where he gets a master’s in philosophy. He’s also about six foot nine, 310 pounds and Black, and I’m walking down the street in Princeton with him and another one of my students—they’re all part of the 400 Club, which means they bench over 400 pounds—and I said to one of them, you know, I’m sure somebody is walking by is going, what are that old dweeby white guy and those Black guys doing together? And I said, I know what they don’t know, which is that you are book nerds, just like I am. And they never had what I or you or most of us had. They did this all by themselves. I don’t want to romanticize prison. There are people who spend all day watching ESPN, and there are people in prison you want to keep away from, but the ones that I teach … one of my students who graduated summa cum laude came into prison illiterate. Imagine graduating summa cum laude from Rutgers University from a jail cell. Let’s just be clear—these people work all day. There’s all the stress of jail, but they also have jobs. A prison wouldn’t function without them. All the work in a prison—the cleaning, the cooking—everything’s done by prisoners, by bonded labor. So they’re remarkable people. I taught Les Misérables one semester in the prison, just because that was the whole purpose of Victor Hugo’s book. And he really wrote it to expose and excoriate the horrible penal system in France—one, frankly, that is not much different from our own.

Robinson

Yeah. And one of those acts of petty cruelty is that when one of your students gets out, they don’t let him have his books. First thing he says is, I’ve got to rebuild my library.

Hedges

Yeah. He had 100 books. Now imagine that. And you have no money. A book is a very precious possession. He’s in for 11 years. That was my first student who got out. First thing he says to me after 11 years in prison is, I have to rebuild my library.

Robinson

Well, the book Our Class will make you angry, but it will also inspire. People should pick up the book and also the play that was written which has been published, which is Caged, available from Haymarket Books by the New Jersey Prison Theater cooperative. Chris Hedges, thank you so much for talking to me.

Hedges

Thank you, Nathan.