Unfortunately We Are Not Living in a “Simulation”

A dangerous new religious belief offers grounds for giving up on the physical world and living 100% online.

More and more people are apparently asking the question: “How do we know we’re not all living in a big computer simulation like in The Matrix?” It seems they are asking seriously. Scientific American has run articles on the idea that the world might be some kind of video game being played by someone outside the Universe. (One piece argues—I hope facetiously—that the speed of light proves that a computer made the universe.) Elon Musk evidently believes this idea wholeheartedly, saying there is almost no chance we are not living in a “computer simulation.” David Chalmers’ new book Reality+: Virtual Worlds and the Problems of Philosophy gives the idea very thorough consideration. Chalmers is not fringe; he is one of the world’s leading philosophers of mind, and his views are taken seriously. (In addition to his professional philosophical work, Chalmers has performed unlistenable music with a band at a music festival for philosophy nerds “where various bands composed of philosophers of mind and neuroscientists perform music about consciousness and qualia.”)

The “How do we know life is real and not just a dream or a hallucination or a kind of sophisticated video game?” question is a longstanding preoccupation of philosophy. Variations on this kind of puzzle have baffled and entranced epistemologists from Plato to Descartes to the present day. I confess they have never held any fascination for me. I have actual work to do on ideas and problems that affect human beings, and wondering whether all of life is actually a dream in the mind of a sleeping butterfly, or the external world is a mere illusion and I am actually a brain in a jar, has long struck me as something of a waste of time. When I took my first philosophy class as an undergraduate, and we were asked to prove that our hands existed, I realized that philosophers would never be my people and resolved that I would stay well clear of their department for the rest of my university years.1 (Amusingly, a Cambridge philosopher once shocked his colleagues when he proved his hands existed by holding them in the air. This was considered an act so daring that it became famous, along the lines of Marcel Duchamp presenting a urinal as an objet d’art, and other philosophers have since issued many very serious responses explaining at length why you cannot prove your hands exist merely by holding them in the air.)

You might be surprised to learn that in Reality+, Chalmers does not just ask how we know we’re not all living in The Matrix. He concludes that there’s a good chance we actually are—in fact, he gives fairly precise odds of it (at least 25%). His book has so blown the mind of New York Times columnist Farhad Manjoo that Manjoo is now a “hard-core simulationist,” meaning they very seriously think the entire world around them might be a big computer simulation produced by the superhumans of another world.

For the same reason I declined to spend more than a single semester debating the reality of my hands, I would rather not give this peculiar delusion the time of day. But at least one of the richest and most powerful (albeit not the brightest) men in the world, Musk, fully believes it. Professional science pedant Neil DeGrasse Tyson says he thinks the “likelihood might be very high.” Chalmers’ new book might make some more converts—the Guardian calls it “convincing.” It worries me that anyone can believe something so silly, partly because I think as a general matter it is better not to be delusional, but also because this type of thinking can actually lead to conclusions that have dangerous real-world implications. So let us consider it for a moment, even if I personally see it as roughly on par with the theory that all of our political leaders are secretly a race of giant lizards. (The lizard stuff is, if anything, more plausible.)

Before we get to the “Is Life Real?” question, let’s start by discussing this whole idea of “simulated worlds.” Reality+ starts with the observation that video games are becoming more and more realistic, and it looks like the trend will continue. Chalmers speculates that, in time, as technology improves, “virtual reality” will become so sophisticated that it is indistinguishable from reality itself. We will someday be able to simulate whole universes, just like in The Matrix. When this happens, we could spend our entire lives living in what is essentially a big video game, without even knowing it.

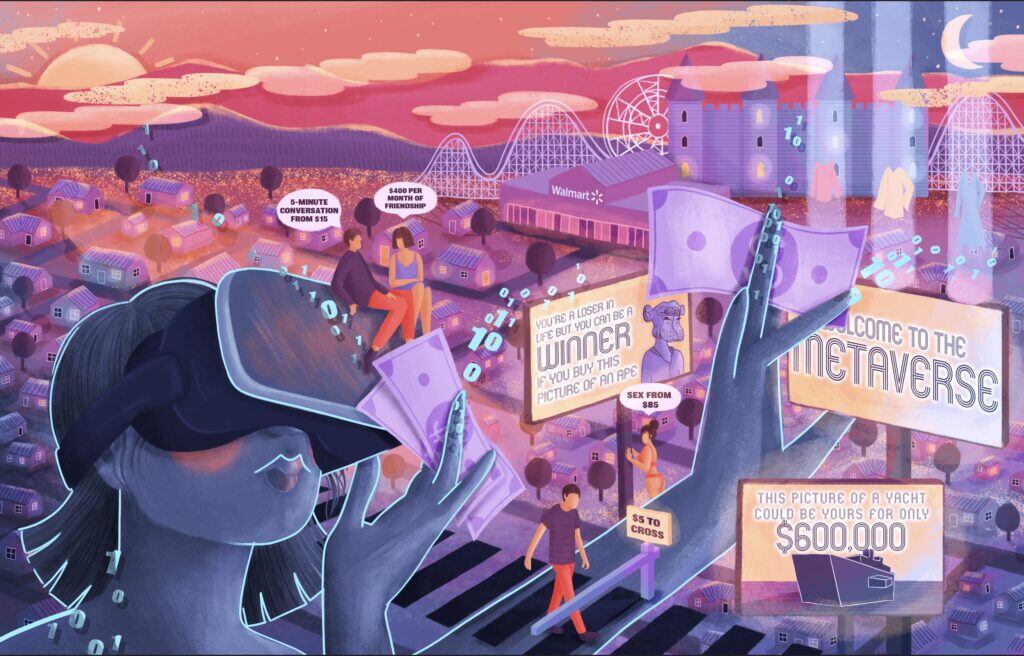

In fact, making “virtual reality” more and more realistic, and getting humans to spend as much of their time in it as possible, seems to be the present ambition of Mark Zuckerberg. He calls this nightmare the Metaverse and has rebranded Facebook as “Meta” to indicate the shift in the company’s ambition from a glorified “book of faces” to an entire simulated universe atop our own. There is much buzz about this “metaverse” that goes beyond Facebook, although the term is still imprecise. But all of it seems to presume we’ll be spending even more time online, whether that’s through “augmented reality” glasses that project our Twitter feeds directly into our eyeballs and populate our surroundings with holograms of catchable Pokémon, or a full Matrix-like VR world, where instead of going to a theme park with your family or climbing a mountain, you visit virtual theme parks with your virtual family and climb virtual mountains of your own creation. In Zuckerberg’s promotional video for the Metaverse, he shows himself living in a virtual dream house, picking out virtual clothes, and attending a virtual card game with virtual friends in virtual outer space, and promises that soon all of these virtual pleasures could be our own. (Forget a future of “sex with robots.” We’ll actually be having sex with virtual robots, mere images, but our brains will be plugged into devices that make our bodies think we are having sex with robots.) Chalmers describes the delights awaiting us:

Sometimes VR will place us in other versions of ordinary physical reality. Sometimes it will immerse us in worlds entirely new. People will enter some worlds temporarily for work or for pleasure. Perhaps Apple will have its own workplace world [oh, joy!], with special protections so that no one can leak its latest Reality system under development. [Workplace protections, on the other hand…] NASA will set up a world with spaceships in which people can explore the galaxy at faster-than-light speed. Other worlds will be worlds in which people can live indefinitely. Virtual real estate developers will compete to offer worlds with perfect weather near the beach,2 or with glorious apartments in a vibrant city, depending on what customers want.

Some of the people who are excited about this whole Metaverse concept see in it the possibility of transcending our earthly limitations and becoming godlike. Humans cannot fly in reality, but in video games they can. You may not be a war hero, but you can play Call of Duty and be a simulated decorated veteran in a simulated world war. You may not be an athlete, but you can be an e-athlete. And the verisimilitude is only going to increase. Considering that we’ve gone from Pong to almost photorealistic video games within a single human lifetime, what will things look like in a hundred years? A thousand? Four million? Surely such things as the Star Trek Holodeck are within reach.

As I say, some people may look forward to this because life is limited and often dreary, and I am sure there are nerds who would love it if they could just live in their video games 24/7. I also like many aspects of the Star Trek future, and there could be something egalitarian about virtual worlds; it’s good that people who can’t compete physically on the football field can still be champions. But I suspect part of the reason Silicon Valley is suddenly excited by the notion of a “metaverse” is that many see a glorious new frontier on which to build their neo-feudal dream world. Once it is agreed that virtual realities are a big part of our future, forward-thinking Entrepreneurs realize that an awful lot of money and power stands to be gained by those who become the gatekeepers of people’s virtual experiences. Jeff Bezos got immensely excited by the internet in 1994 because he saw that it could make him filthy rich: whoever built the first big successful online marketplace could use their power to crush competitors, and basically own the infrastructure through which buying and selling occurred online. It’s like building all the roads in a new country, and getting to keep private control of them. Becoming the person who owns the basic infrastructure and charges usage fees in perpetuity will be immensely lucrative. If Mark Zuckerberg establishes a colossal virtual reality platform that becomes the default way that people get online, the Company Formerly Known As Facebook can apply its existing business model: selling people’s attention to advertisers, only this time it won’t just be things that pop up in your news feed. The entire “virtual world” itself can be constructed in whatever way will most effectively manipulate its users and enrich its creators. Plus, Zuckerberg himself can feel like a human deity who has created the world, which I am sure is part of the appeal. (I realize this sounds ludicrous, but a popular Silicon Valley “intellectual” literally has a book called Homo Deus telling these people that their destiny is to become living gods.)

One of the problems with selling people on the idea of spending more time in virtual reality is that, at the end of the day, it is still virtual. Even if your simulated house in the “Metaverse” has a better view than your real house, it’s a fake house, and you know it’s a fake house. A picture of a thing is not the same as the thing itself. The YouTube comments section on Zuckerberg’s promotional Metaverse is not exactly full of people elated by the idea of replacing their dismal “meatspace” experiences with the infinite possibilities that come with living full-time in a cyber-world. The word “terrifying” is used frequently. “Mark’s vision of the future is a massive escape from reality,” says one. Someone else comments that it seems an “incredibly hollow and depressing existence.”

But in Reality+, David Chalmers argues that these people are wrong. Chalmers is excited by the possibilities of living in virtual reality. In fact, one of the main arguments of the book is that living in virtual reality is not a “detachment” from reality, because a sufficiently immersive digital world becomes the real world. He writes that:

“Virtual worlds are not illusions or fictions, or at least they need not be. What happens in VR really happens. The objects we interact with in VR are real. Life in virtual worlds can be as good, in principle, as life outside virtual worlds. You can lead a fully meaningful life in a virtual world.”

To make this case, Chalmers offers a definition of “real” that departs from everyday usage, and encourages us to adopt it. He gives the example of two kittens: a live kitten and a virtual kitten simulated by a computer. We may say that the live kitten is “real” and the virtual kitten is “not real.” But, he says, both are real. One is a biological entity and one is a computer program. But both exist, and are therefore real. Likewise, if you buy a house in the Metaverse, the house is real. It’s virtual. But it’s real. He is not saying there is no difference between the two things, but rather that since “reality” encompasses both things that happen in simulations and things that happen in the offline world, virtual realities are real. “[Virtual kittens] exist, they have causal powers, they’re independent of our minds, and they need not be illusory. One day in the virtual future, we may even recognize virtual kittens and biological kittens alike as genuine kittens.”

I am not particularly impressed by this. Essentially, Chalmers enumerates a checklist of things that make things “real.” He says a thing is “real” if it exists, if it can cause things to happen, if we can’t wish them away with our minds, if it is what it seems, and if it is genuine. Then he proceeds to argue that in a sufficiently immersive virtual world, virtual things can possess all these qualities. One’s instinct might be to argue that he’s wrong to say a digi-kitty “is what it seems.” But more importantly, this is his personal list of criteria for applying the word “real.” It departs from ordinary usage, in which in order for a thing to be “real” it is “not simulated on a computer.” If you want to redefine the word “real” in order to include virtual kittens, by dropping “not simulated on a computer” from our understanding of what makes something “real,” you’re not wrong. But it’s not “true” or “false” that a “virtual kitten is real.” It just depends on how we want to define the term.

Many arguments that are ostensibly about what things “are” are actually about what words we should use to describe them. Noam Chomsky, discussing the question “can computers think?” says that it is like asking “do submarines swim?” The answer in each case is “it depends how you choose to define the word.” If you define swimming as self-propulsion through water, then, yes, submarines “swim.” If you define swimming as self-propulsion through water by animals, then, no, submarines don’t “swim.” We could have a long debate about whether computers “can” or “can’t” think, but we’re really just debating whether the thing that computers do is something we want to attach the word “think” to. There is no right answer to the question. (This happens to also be why transphobes like Ben Shapiro are in error when they say that trans women “aren’t” women. What they’re really saying is that they use the word “woman” in a particular way—to refer solely to cisgender women—and they’re unwilling to alter their usage.)

Chalmers’ idiosyncratic definition of the word “real” leads him to odd places. If we all wear “augmented reality” headsets that produce a believable hologram of a piano in the park, and if when you move your fingers through space, the piano “plays,” Chalmers says the piano is a “real piano.” It’s not a physical piano, he freely admits. But it’s real. He even suggests that the Pokémon in Pokémon Go may be considered real.

As I say, this isn’t “wrong,” it’s just advocating for a new kind of usage that may lead to misunderstanding. In everyday use as it stands now, we do not say that the Pokémon in Pokémon Go are “real,” because in that context “real” is understood to mean “things that are not simulated by computers.” If I told you I saw a real Pokémon in the park while I was playing Pokémon Go, you would understand me to be saying that I had seen something outside the simulated reality of the game, even though the game is obviously “part of reality” in a different sense. I essentially think Chalmers is just making an argument for adopting a confusing new convention for applying the word “real” that will make it harder to tell the difference between virtual reality and physical reality. Indeed, that is precisely what Chalmers foresees happening: eventually, as our simulations become more precise, the distinction between virtual kittens and real ones may cease to matter to us. We will no longer consider time spent in the Metaverse, or the Holodeck, or virtual reality to be “detachment from reality,” because we will have adopted Chalmers’ definition, according to which things once described as “fake” or “illusions” are now indistinguishable from the real world. Chalmers does not consider this a bad thing. He writes:

Many of us already spend a great deal of time in virtual worlds. In the future, we may well face the option of spending more time there, or even spending most of our lives there. If I’m right, this will be a reasonable choice. Many would see this as a dystopia. I do not.

Chalmers goes on to make the argument that “meaningful lives” can be lived in “virtual worlds.” I don’t necessarily disagree with this, since “meaningful lives” have been lived even in concentration camps. Humans are very resilient. But I do think if you admit that a whole lot of people find the world you’re proposing to be “a dystopia”—that is, a horrific nightmare of a place—and you find yourself having to try to convince them that they are wrong and actually can live meaningful lives there, perhaps it is not they who are mistaken about the wonderfulness of the brave new world. Perhaps you are mistaken about what makes life meaningful to people who are not like yourself.

That’s where I think all of this becomes downright dangerous rather than merely irritatingly masturbatory. I would not be surprised if the tech community signs on wholeheartedly to Chalmers’ view that we should cease to even make the distinction between virtual reality and reality itself. Fortunately, the virtual worlds that Zuckerberg et al. have envisioned thus far are so bleak and soulless that it’s hard to imagine them being voluntarily inhabited by anyone who doesn’t already spend most of their waking life plugged into a gaming console. But I can certainly imagine that our corporate overlords are going to put a great deal of effort into convincing people that their lives in the insipid soulless metaverse are just as good as life here in the actual universe.

Ah, but is it the Actual Universe? That is the question. Chalmers not only thinks virtual reality will someday be worth living in on a full-time basis, but that we may well already be living in it. This is what is known as the “simulation hypothesis.”

Why should anyone believe that we are living in a computer simulation? Is there any observable evidence for this? Well, no (setting aside the guy who thinks the speed of light proves it to be the case). The arguments Chalmers cites are based on a story, and some speculative probabilities. The most popular formulation of this comes from Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom (a popular thinker among Silicon Valley “rationalists,” whose work has been critically discussed in this magazine on multiple occasions) in a 2003 article called “Are You Living In A Computer Simulation?” The rough idea is that virtual reality will continue on the path toward greater and greater realism, to the point where everything we experience could be replicated virtually. We will have the technology to produce something like the Matrix, an entire simulated universe. Perhaps this will be in the far future, but it will happen. Once it does, future-beings will create lots of simulations of the past and populate them with simulated creatures (sometimes the argument is that they will be humans plugged into computers, sometimes it’s that they will be computers themselves, somehow made sentient). They will do this so much that there are billions more simulated realities than the one actual reality. Statistically, then, the odds are that any given creature that finds itself conscious is probably in one of these simulations, rather than the “real world.”3 As Musk articulately puts it:

“Even if the rate [of technological advancement] drops by a thousand from right now—imagine it’s 10,000 years in the future, which is nothing in the evolutionary scale. So given we’re clearly on a trajectory to have games that are indistinguishable from reality and those games could be played on a set top box or on a PC or whatever and there would be billions of such computers or set top boxes, it would seem to follow the odds we’re in base reality is one in billions … Tell me what’s wrong with that argument. Is there a flaw in that argument?” 4

I realize you might find this all batshit crazy. I can promise you that I do not take it seriously either. But it is one of those ideas that sounds self-evidently nutty but can be difficult to spot the actual flaw in. Neil deGrasse Tyson said that “I wish I could summon a strong argument against it, but I can find none.” Tyson may be very, very annoying, but he is not stupid, and it may be hard to identify what precisely is objectionable about the reasoning: Are we confident that human technology won’t advance to the point where we can create realistic simulations of a human life? Do we think future people wouldn’t create simulations? Do we think that it would always be easy to tell if one was in a real reality or a simulated one?

In seeing why the “simulation hypothesis” doesn’t make sense, I think it helps to first notice that in many ways, it simply re-words the foundational concepts of theism in language more palatable to technophiles who don’t think of themselves as religious. What, after all, is this hypothesis arguing? It’s saying that the world we live in, the universe and all that we see and experience, was intentionally created by a human-like someone. It was designed. That someone is essentially omnipotent (if the world is a big computer program, presumably the programmer could reprogram it or turn it off). And if they wanted to, they could be omniscient, although perhaps they’re not watching us all the time. They live outside the world we see. They are, then, an invisible creator-being who put all this here for a reason.

Chalmers admits that the simulation hypothesis is essentially theism. “The simulation hypothesis has made me take the existence of a god more seriously than I ever had before,” he says. But he insists that believing we “live in a simulation” (again, a techie’s way of saying that our world was intelligently designed by a powerful human-like creator for a reason) does not make one religious, because religions have moral codes and demand you worship the deity:

“Religions … typically entail forms of worship. … [W]here gods are involved, worship is the rule… [E]ven if our simulator is our creator, is all-knowing, is all-powerful, and is all-good, I still don’t think of her as a god. The reason is that the simulator is not worthy of worship. And to be a god in the genuine sense, one must be worthy of worship. For me, this is helpful in understanding why I’m not religious and why I consider myself an atheist. It turns out that I’m open to the idea of a creator who is close to all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-good. I had once thought this idea is inconsistent with a naturalistic view of the world, but the simulation idea makes it consistent. There remains a more fundamental reason for my atheism, however: I do not think any being is worthy of worship.”

Just as Chalmers redefined reality to include things nobody currently considers to be real, he has here redefined “atheism” to include the very thing that atheism is not, i.e., believing in a god. Chalmers insists that so long as you don’t advocate worshiping God, you can still be an atheist. But unless we grant him a personal exemption from the dictionary definition of words, this isn’t so. Chalmers is a deist or theist. I think this is embarrassing for him to admit, because he is a committed rationalist. But if he is religious, he should own up to it, and not pretend to be an atheist. (As I said before, we’re allowed to redefine words if we want to, so we can start using the word “atheist” to mean “deist” if we find that useful, but since the word “deist” is tailor-made for the position Chalmers is describing, there’s no reason not to stick with it.) Chalmers is reluctant to admit that the stance is religious, and must cling to the incoherent idea that he’s “an atheist who believes there might be an all-powerful, all-knowing, all-good god.” Once reason for his reluctance may be that once we notice this whole “simulation hypothesis” really isn’t different from good old fashioned belief in a god (except that God is a computer now, or a humanlike person operating one), the old arguments against believing in God now come up against the simulation hypothesis—and many of those arguments are quite good.

The big problem with believing that our world and everything in it was created on purpose by an intelligent being is that our world is incredibly fucked-up and absurd, and in order for our world to have been created by an omnipotent, omniscient Somebody, said Somebody would have to be a sadistic psychopath who chose to create a world featuring horrible pain and suffering on a colossal scale when they could just as well have not done so. The problem of evil is one of the major intellectual challenges to religion and debates about it have gone on for many centuries. Chalmers addresses it briefly and inadequately, saying in part:

A theodicy is a theological explanation of why God might permit evil in the world. A simulation theodicy does the same for simulators. One simulation theodicy says that a good simulator should create all worlds with a balance of happiness over suffering. This will lead to worlds with considerable suffering, so long as it is outweighed by happiness. If the simulation hypothesis is true, perhaps this idea could even explain the existence of evil in our world. Or perhaps our simulators are not especially benevolent and have priorities other than the well-being of the creatures they create. Another simulation theodicy says that simulators aren’t omnipotent and so cannot predict everything that will happen in a simulation.

These are the same old excuses for God’s misdeeds that have long been given by theologians. Maybe the world is good on balance. (But, still, why the horror?) Maybe God created the world but doesn’t or can’t intervene. (He’s unable? Unwilling? Why?) Or maybe we’re dealing with a vengeful Old Testament type.

I never found any of it persuasive, and I don’t even when God has been rebranded The Great Simulator. Atheist Stephen Fry, asked what he would say if he found himself face to face with God in the afterlife, replied: “I’d say: Bone cancer in children? … Why should I respect a capricious, mean-minded, stupid God who creates a world that is so full of injustice and pain?” Joseph Heller, in Catch-22, had Yossarian articulate a version of the same argument:

“Good God, how much reverence can you have for a Supreme Being who finds it necessary to include tooth decay in His divine system of creation? Why in the world did He ever create pain?”

“Pain?” Lieutenant Shiesskopf’s wife pounced upon the word victoriously. “Pain is a warning to us of bodily dangers.”

“And who created the dangers?” Yossarian demanded. “Why couldn’t He have used a doorbell to notify us, or one of His celestial choirs? Or a system of blue-and-red neon tubes right in the middle of each person’s forehead?”

“People would certainly look silly walking around with red neon tubes right in the middle of their foreheads.”

“They certainly look beautiful now writhing in agony, don’t they?”

Now, you can reply that just because The Simulator a.k.a. God has chosen to create a world filled with horrible injustice, this does not mean they don’t exist. But note a critical point in the argument that we “are probably living in a simulation”: it says that when technology gets to the point where a universe like this, filled with first-person experiences like ours, could be “simulated” with computers, humans would and will do this. Bostrom tells some story about how they’ll want to replicate the experiences of their ancestors in order to learn things, and that they’ll do it billions of times or something. But I happen to think that building giant (universe-sized) “Truman Show” type experiments, and reenacting World War II and watching children die of preventable cancers, is such a profoundly immoral act that our future-human descendants would have to have become complete monsters in order to do it.

Remember what we’re talking about in this ridiculous speculative scenario: we’re talking about people creating immersive virtual worlds. And we have to come up with a story in which they chose to create this one. This is the “video game” that someone chose to play. To look over history, to see all the famines and wars and plagues, to see all the broken hearts and maimings and airplane accidents, one cannot possibly give a reasonable explanation why anyone would do this. Supposedly these future humans have such powerful computers that they can do things far beyond what we are capable of now. They could program anything. If we can reprogram The Sims, they could certainly answer the prayers of people who are watching their loved ones die. If, as Chalmers promises, NASA can build us a “world with spaceships in which people can explore the galaxy at faster-than-light speed,” why did the much-more-advanced post-human future-race build this bullshit world in which the goddamn arbitrary speed of light is keeping us from meeting cool aliens? We are apparently to believe that these “post-humans” decided that instead of using their technology to have endless orgiastic fun in ways presently unfathomable to us, they used it to make a world in which everything is killing each other pretty much all of the time and Hiroshima got wiped out with a nuke. Why, God, why?

There’s a quote I like from Kurt Vonnegut: “I do feel that evolution is being controlled by some sort of divine engineer. I can’t help thinking that. And this engineer knows exactly what he or she is doing and why, and where evolution is headed. That’s why we’ve got giraffes and hippopotami and the clap.” Our world is not just full of evil, but is fundamentally ridiculous, littered with signs of accident rather than intentionality. Accepting that the world wasn’t designed by an intelligent being ends up being liberating. You cease having to wonder why there is so much horror and meaninglessness in it, and can start being amazed that there is so much that is wonderful in it.

So one good reason to think this world is not a video game is that it is nothing like the sort of worlds we would “simulate” if we had the technology. The whole point, presumably, is that we want to transcend the stupid, awful things that make this life so tragic. Our simulations are supposed to be places where we don’t spend hours sitting in a hospital waiting room dreading bad news about our loved ones’ conditions, and as our technology improves, presumably we’re not going to get any more likely to want to “simulate” the feeling of suicidal depression or back pain. (One of the reasons the original The Sims game got boring is because it too closely simulated this world, and you had to spend a lot of time exercising and going to the bathroom and working. This is why they soon added an expansion pack with robots and genies.)

I actually do not think it is an accident that the people to whom the “simulation hypothesis” has been most appealing are wealthy, comfortable, mostly-white men. The better your life is, the more it resembles the kind of story you might find in a video game (e.g., you’re a billionaire who makes rockets), and the more plausible this nonsense becomes. Those who believe this seem oblivious to what the world is really like for many of its residents, and just how drastically it departs from “a really complicated video game.” In fact, I would go so far as to say that the hypothesis is most plausible for a certain type of blinkered extremely-online guy, who does not read much history or spend much time in nature. (Indeed, Chalmers’ reference points outside philosophy tend to be things like Marvel movies and Rick & Morty.) I think the people who don’t see too much of a difference between a tree or kitten in real life and a tree or kitten in a video game simply don’t know much about trees or kittens, and already live mostly in a cheap simulation made of very superficial images. I also do not think it is entirely coincidental that two of the prominent scientists I have seen heaping cold water on this hypothesis in the press are women. Harvard theoretical physicist Lisa Randall has said that the chances that we are “in a simulation” are “effectively zero,” and “I don’t know why this higher species would want to simulate us.” She says the actual interesting question is “why so many people think it’s an interesting question.” Another theoretical physicist, Sabine Hossenfelder, has said that it “just isn’t a serious scientific hypothesis” and “you’d have to believe it because you have faith, not because you have logic on your side.” She notes that those who find this plausible seem to take the idea of reproducing the entire known universe on a computer as not just possibly feasible, but virtually inevitable, but that “they don’t explain how this is supposed to work.” Indeed, in Reality+, Chalmers doesn’t give much actual detail of how computers are going to create the entire universe, beyond the fact that Call of Duty games are better than they were in 2003, time and the market will bring further improvements, and time and the market will presumably keep going for a good long while.

I see no good argument for believing that “we are in a simulation.” I think people who conflate virtual reality and reality will someday discover that the real world was a much richer place than they knew, and that their excessive confidence that the “metaverse” could be just as good came from the fact that they’d failed to notice all the ways in which simulated things are woefully inferior. (“Ah, but if they keep improving, then eventually…!” Okay, call me when they do.) But people who are—and I realize this sounds snobby—uncultured, by which I mainly mean raised on video games, might not notice the difference between an “NFT” of an ape and an actual beautiful piece of physical artwork. If you are raised in a world of images, if you rarely go offline these days, you might indeed find yourself in the very sad position of forgetting what it’s like outside, and wondering why we even bother distinguishing between images and reality at all. I pity those who tell themselves they’re happy in Chalmers’ Definitely-Not-A-Dystopia. They will be missing so much out here. They’ll be like those who erect a giant photo of a tree when they could have an actual forest. They will unintentionally obliterate everything with value because they couldn’t see how ignorant they were.

These ideas are not just sad, they’re disturbing. You might be tempted to think it makes no difference whether we’re in a “simulation” or not, since we’re stuck in the world either way, but economist Robin Hanson has argued that those who believe they are in simulations might find themselves coming to different conclusions about how to act: “your motivation to save for retirement, or to help the poor in Ethiopia, might be muted by realizing that in your simulation, you will never retire and there is no Ethiopia.” If you genuinely did think the world was a big video game in which you were the protagonist, you might feel justified in acting as if other people didn’t matter. “There is no Ethiopia,” just as “there is no spoon.” People blurring the lines between virtual reality and reality might develop frightening kinds of mental illness—notably, the Christchurch mosque shooter in New Zealand live-streamed his rampage as if it was a first-person shooter video game, and probably thought of the worshipers he massacred as mere “NPCs.”

Chalmers acknowledges that his “virtual reality is reality” stance leads to some uncomfortable places, citing an episode of the sci-fi TV show Black Mirror in which a soldier kills creatures he perceives to be insects, but which are in fact humans, his perception having been altered through a neural implant. Under Chalmers’ framework, the roaches are “real.” He notes that humans are still dying, which is true, but the equality of the two realities has troubling implications when we combine it with Chalmers’ idea that computer-simulated people could themselves be conscious, and “we have roughly the same obligation toward sims [computer-simulated people] that we have toward nonsims [non-computer-simulated people].” He seems to think that video game characters could be sentient (after all, the world might be a video game, and we’re sentient ourselves), which leads to the possibility that one should commit harm against human beings in order to be heroic in the virtual world. If virtual people are treated as real and morally worthy, then the rights of real people might be abridged to favor the interests of the “sims.” Chalmers even says that “It’s easy to imagine a struggle to grant sims the same rights as ordinary humans … if Martin Luther King Jr. was right that the long arc of the moral universe bends toward justice, then the arc will bend toward granting equal rights to sims.” We need the MLK of NPCs!

Personally, I think treating computer simulations of humans as if they can be conscious human beings is a deranged kind of anthropomorphization—like drawing a happy face on a rock and claiming the rock has actually become happy. But to those who believe that human beings themselves are probably just computer programs, and pictures of trees are trees if they convince you they are, there is no limit to the loopy moral conclusions you can come to. I only pray that nobody ever actually takes this very seriously. (You can do a public service by savagely mocking anyone who believes it.)

Chalmers is probably the kind of philosopher who has just spent too much time living in his head and forgotten what the world is like. I don’t think he’s malevolent. But people who believe his theories pose a serious threat. I am certain that the wealthy and powerful will eat up the idea that virtual reality is just as good as this reality, because it gives a great new rationalization for trashing the Earth. After all, who needs it? The Earth is probably just a simulation anyway, and we will soon make better ones with more varied animals and where you can be anyone you like. The climate never changes in the Metaverse.

Reality+ will hopefully remain obscure and be read by few, but it could be used to justify a quite demented kind of vision: the rich keep this world as their playground, the rest of us are shunted into the Metaverse, which we’re told is actually even better. It’s not far from what is actually happening, of course: Facebook and video games can addict and deactivate people, making the corporate conquest of our politics easier. The good news is that any virtual reality designed by the boring, cultureless weirdos of Silicon Valley is not going to attract many voluntary permanent occupants. The bad news is that a class of people with a lot of power may be losing touch with reality and convincing themselves that their destiny is to become earthly gods who control our every experience. Those of us who still inhabit reality must do our best to keep our friends and loved ones anchored here.

Maybe it’s unfortunate that we’re not living in a “simulation.” It would certainly put my mind at ease. Even the destruction of the world wouldn’t matter too much, since someone could just fire up the program again and start anew. Alas, we do live in the world, and it’s really real, and we’ve only got one of them. We’d better take good care of it, because there are no “billions of simulations” to take its place.

Illustration by Kasia Kozakiewicz.

A confession I must make is that I occasionally go so far as to suspect the world would be better off without any philosophers. As far as we know, there are no philosophers among the bonobos or the manatees, and they’ve managed to produce far more attractive societies than we homo sapiens have put together. Has philosophy ever really done us any good? Can the act of philosophizing even be morally justified? Has the “trolley problem” ever actually improved anyone’s real-world moral decision-making? Whenever I read the pedantic, unproductive, smug terminological quibbling of Socrates in the Platonic dialogues, I am honestly surprised the ancient Athenians did not get out the hemlock sooner. I realize this may be an intellectually indefensible position, but I just suspect I would personally be happier living in a town composed of gardeners and lighthouse-keepers than a town with philosophers in it. Letters to the editor in response to this endnote will be discarded unread. ↩

Note: theoretically the one distinct advantage to living in a virtual economy is that it should be a “post-scarcity” world in which anyone can have anything they want, but the capitalists who are plotting out our virtual future are trying their best to think up ways to impose artificial scarcity, e.g., by selling virtual real estate for real money. ↩

Note: the “real world” from which these simulations come may or may not also be a simulation. ↩

Incidentally, Musk admits he has become rather unhealthily obsessed with this pet thought experiment: “I’ve had so many simulation discussions it’s crazy… It got to the point where every discussion was the AI or simulation conversation and my brother and I finally agreed we would ban such conversations if we were ever in a hot tub because it really kills the magic.” ↩