How America Criminalizes Black Youth

From stop and frisk to metal detectors in schools, many Black youngsters are regularly treated with suspicion in their own communities. This has damaging and lasting effects on their lives.

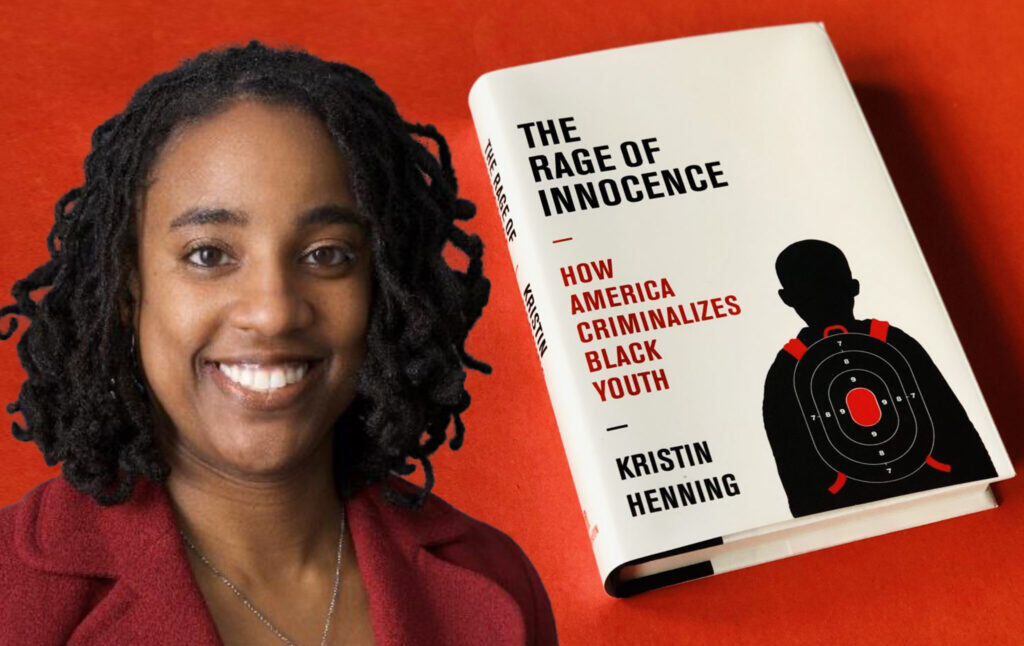

Professor Kristin Henning directs the Juvenile Justice Clinic at Georgetown University Law Center. She is the author of the book, The Rage of Innocence: How America Criminalizes Black Youth. Prof. Henning recently discussed her book on an episode of the Current Affairs podcast with editor in chief Nathan J. Robinson. The interview has been lightly edited for grammar and clarity.

Robinson

There has been a lot of national attention paid to the shootings of young Black men and women by police in the United States. And when there are fatal shootings of children, like that of Tamir Rice, for example, they do get national news coverage. You write about those cases in your book. But you also draw our attention to the fact that apart from the cases of deadly violence by police, there is a whole everyday regime of surveillance and violence that young Black boys and girls grow up with. Could you explain the aspects of life for Black youth that you really want to draw attention to by writing and publishing this book?

Henning

Yes. Thank you so much for that question, because it so often gets missed in the hubbub of the conversation about extreme examples of violence. But in a city like Washington, D.C.—and it’s not just D.C., it’s throughout the country—there are pockets of communities where Black and Brown children have grown up under the constant surveillance of police officers. So I talk about my clients, who share stories of literally coming outside of their homes and seeing police officers parked on a street corner, parked in the nearby recreation center. They encounter police officers when they enter a convenience store. They might encounter them on the way out. Police officers stop them and ask them, “Where are you going? Where are you coming from?” They get asked, “Can you lift your shirt?” The police officer asks a young person, “Can you lift your shirt so that I can see your waistband and be sure that you are not carrying a weapon?” And I think most of us take it for granted that we can walk through our neighborhoods and our communities and not experience these undue intrusions by law enforcement. But so many Black and Brown children don’t enjoy that basic privilege. And it’s really traumatic for them.

Robinson

What does it do to a child to be raised and to go through life every day encountering police officers routinely? I assume it creates a constant state of fear and anxiety at a kind of low level.

Henning

You nailed it. There is now a growing body of empirical research that documents the extraordinary psychological trauma that policing imposes on Black children at the most important time in their lives, their adolescent development years. That research shows that Black children—and also Latino children as well—who live in heavily surveilled neighborhoods, and who are the frequent targets of stop and frisk, have high rates of fear, anxiety, depression, and hopelessness. They become hypervigilant, meaning that they’re always on guard and distrusting of police officers. And what’s really significant is that the distress transfers over to other adult authority figures, like teachers, at times. And then the research goes on to show us that young people in these communities also report great disruption in their sleep patterns. Sleep is something that we take for granted. Young people who have been the frequent target of stop and frisk report really poor sleep quality, or not being able to sleep at all. It has a profound impact on adolescent identity formation, which is one of the most important things that happens in our adolescent years. So negative encounters with the police have an impact on the way young people see themselves, feel about themselves, and how they think they fit into the world and in relationships with other people. And then the final thing that I think is really important for all of us who care about public safety is that early negative encounters with the police have a profound impact on the ways in which young people think about law and law enforcement, whether or not law enforcement is legitimate and fair, and whether it’s even worth it to participate in mainstream society, based upon how how they are treated.

Robinson

For every incident of the police doing something to someone, that has ramifications beyond even its consequences for the person who is targeted. It’s like with the history of lynching. The number of lynchings was very high. But also the ramification of lynching was that every single other person was on notice and had to live in constant fear. So even the youth who are not, in fact, stopped or frisked are affected by the fact that at any time they could be stopped or frisked.

Henning

Absolutely. And I write about that quite a bit. Just having to get up in the morning and worry about whether or not you will be the next target of some sort of police violence, is significant. And when I talk to police officers, I say to them, You have to remember that the blue uniform carries with it the history of race relations in America, and so even when you approach a young person with the best of intentions, even in a wellness check, you have to understand that that Black child has now watched on TV or on the internet other examples of police violence. And research shows, just as you talked about, that there is an association between what they call traumatic events online and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). So just watching on TV or the internet the killing of George Floyd or the death of Tamir Rice is truly just as traumatic as being there and leads to post-traumatic stress disorder—in the same way people experience PTSD from watching on television the Twin Towers collapse, the Boston Marathon bombing, and watching people stranded on bridges after Hurricane Katrina. These examples show evidence of PTSD throughout the community. That research is now being replicated in light of what people are seeing police do on television. And one thing that I’ll say response to your question is that, in the era of lynching, that was very much intentional. The lynching of Emmett Till was absolutely a symbolic statement in the heart of the civil rights era, after Brown v. Board of Education, that we will not tolerate integration. And so it became, as you said, a symbol. It put everyone on notice, to stay in their places. And now, I think much of the police violence operates in the same way, even if it’s not intentionally laid out and methodically planned in that way. We have biases as a society, and the fears that we have of Black children are just unfounded, even in the face of temporary upticks in violent crime. The data does not support this notion that Black children, collectively, are a terror in society. But it is those types of biases that lead to the shootings that indeed set the stage and frighten all Black children into some sort of submission, and it can limit opportunities and lead to death.

Robinson

And every day these children have to live knowing that the burden of proof is on them to show that they’re not a danger. If they don’t want to be asked to lift their shirt, if they don’t want to have a gun pointed at them, they have to monitor all of their behaviors to try and not give any tip offs or signs to authority figures that are going to lead to an incident. That effort must occupy an enormous portion of a child’s brain power. They go through the day thinking, how am I going to get through the day? How am I going to avoid an unpleasant confrontation?

Henning

And think about how incredibly hard it is to do for an adult, right? So you just articulated what the survival mechanism is for a Black person trying to navigate policing in America, or perceptions of policing in America. You can see how much psychological space it occupies. But what do we know about adolescents? Adolescents are impulsive. They’re reactive. They’re emotional. They’re fairness fanatics. They often lack the language to articulate to a police officer, “Mr. Officer, I comply.” Anything that we expect adults to do is that much harder for an adolescent whose brain is still developing. So it’s a tall order. Sometimes Black children have been told by their parents—they have been given the talk: “Do whatever you have to do to get home safely. Just do what the officer tells you to do.” Black children try to do so, to the best of their ability. But that moment of impulsivity kicks in, and they act like any teenager of any race would act in that moment. Part of the title of my book is “the rage of innocence.” At a macro level, the “rage of innocence” is that rage that any of us should have, or all of us should have, when any one child is deprived of an opportunity to be a child. But here’s the deal. The “rage of innocence” also refers to the rage that Black children have when they are told over and over again that they’re bad and that they’re criminal, that they’re not worthy, that they should be excluded from society. And any self-respecting human being with an ounce of dignity is going to resist those labels. So they might speak out, and they might push back, and they’re not gonna be able to do it like you and me. They’re not gonna say, “Mr. Officer, I don’t appreciate the way you’ve talked to me.”

Robinson

“Excuse me, sir, I object to my treatment.” Kids are kids. This is one of the important things that comes out in your book: the idea that every child deserves to be a child. And that even includes some level of sympathy for misbehavior, or acting out. You begin the book with this story of your client, Eric, who tried to make a “Molotov cocktail”—in the way that kids who have only seen something on television try to do, because they have no idea what they’re doing. And then the reaction of the system to that is as if he was actually some kind of terrorist threat to the school. Instead of going like, Oh, my God, Eric tried to make a “Molotov cocktail,” because he saw it on TV, because kids are kids and they do silly things. You have to have some kind of indulgence. I got plenty of indulgence as a child.

Henning

Exactly. In this book, I really try hard to tell stories that will allow the reader to see themselves—just as you just said—as a child or to see their own children in the stories doing what children do. This notion of not giving grace and indulgence for children to be children really has a racial overlay, right? As you point out, I tell the story about Eric making this “Molotov cocktail.” Or attempting to make it without researching it at all. He’s not getting on the internet, but he’s literally throwing liquids in a bottle—mind you, the liquids that he chose would not be flammable—and so he accidentally puts the bottle in his book bag. And he forgets all about it. This was on a Saturday night. Monday, he goes to school and puts his book bag through the metal detector. And a school resource officer [law-enforcement officer in school] finds it and says, “What is this?” The boy immediately says, “Oh, that’s nothing, you can throw it away.” And he doesn’t think anything of it. Next thing he knows, he gets arrested, the fire department comes, and they haul him off to court where he has a nine month ordeal. But here’s the racial overlay. This is really part of why I wanted to write this book. I’m giving a lecture in Connecticut some time later, and I share Eric’s story with the audience. And a white woman comes up to me after. She says, “My son did the exact same thing.” And I asked her what happened. And she says, “He got placed in advanced chemistry classes.” That’s what we do. I mean, he’s 13 years old.

Robinson

He had to put his book bag through the metal detector—I never had to put my book bag through a metal detector. Never once. That never happened. That’s another thing, the presumption against young people. Every young person is suspect. They have the burden to prove that they are not bringing some kind of weapon into school to hurt people. Instead, we could just assume these are children that are almost certainly not trying to hurt people since they’re children.

Henning

Right. The data shows, again, that school resource officers are disproportionately present in schools that have a high percentage of Black and Brown children. And what was so fascinating about doing some of the research on the presence of police in schools, is that I bought into the long-repeated narrative that we have police in schools because of the mass shootings that took place in the 90’s, like Columbine. One thing that I learned in the research was that, actually, the first police officers in schools appeared back in 1939, in Indianapolis, with the earliest conversations about integration. And then the school police presence increased dramatically in the civil rights era, when police officers were set under the purported mission of facilitating integration. And we know through iconic pictures all across the country, and through the research that we have, that many police went to those schools to impede those integration efforts. And the National Association of School Resource Officers was actually founded in 1991. That is eight years before the mass shooting in Columbine, Colorado. The National Association of School Resource Officers really grew up in response to that temporary uptick in crime in the 1990s. That led to the super predator myth, this pseudoscientific myth that Black children were going to run amok and maim and kill and rape all these people. None of that turned out to be true. There was a temporary uptick in crime, but none of that became true. Crime plummeted. But yet Black children became the primary targets of police surveillance following the 1990s. So now we have schools that have received federal funding to increase their presence of school resource officers. And guess where the police officers go? They don’t go to the suburbs like Columbine, where many wealthy white youth or middle-class youth appear. Instead they get sent to predominantly Black and Brown schools.

Robinson

In your career as a defense attorney and leading the Juvenile Justice Clinic, you’ve dealt with so many children, and you must find that it really turns kids off to school when schools resemble prisons. Schools are full of guards, right? To have to go through the metal detector to get there—to build this kind of institution where the authority figures dehumanize you—has got to have an effect in making children less likely to be interested in whatever school has to teach them.

Henning

Absolutely. And there’s been research to back it up. And it’s absolutely right. Young people say, I don’t want to go to school, I don’t want to be harassed. Every time I walk through the front door—Black and Brown children with disabilities experience the brunt of use of force by police officers. There is case after case. Lately we’ve seen school resource officers body slamming a child in school or arresting a child in school for normal adolescent behaviors. And I want to be really clear about this: I’m not implicating all school police officers by any stretch of the imagination. Many police officers asked to be assigned to school, because they care about children. But what we’re talking about is the phrase you used: the extension of policing, from the community into the schoolhouse, and creating a school climate that is indeed dehumanizing. That makes young people feel like they are always being critiqued and not welcome. And school is the one place that children are allowed to go and feel safe. And they don’t feel physically safe. They don’t feel psychologically safe. The empirical research shows that in schools where there’s a heavy police presence, the related stress that arises from that reduces academic performance. It increases school discipline beyond what is traditional and normal as a response to adolescent behavior. Therefore, it becomes easier for teachers to rely on police officers in schools to handle routine matters of school discipline. You see children getting arrested and the like.

Robinson

It’s also notable that a lot of the disciplinary procedures further impede students’ ability to learn. I always found it weird that if you misbehaved in school, you got suspended from school. That can’t possibly help at all. And when it’s more extreme, when it’s arresting kids and thrusting them into the bureaucratic machine of the juvenile justice system, which takes a ton of time, a ton of energy, which introduces this whole new procedure that is about to occupy the child’s life. I mean, it just makes it harder and harder for a child to have the time to focus on the things that supposedly we want them to do. The sensible thing to do with a kid with a Molotov cocktail is to say, Okay, well, we’re going to use this as an opportunity to have you focus on chemistry because what we want the child to do at school is to learn chemistry. So how can we take this and channel it into something that is going to make them better at school, rather than do something that is going to actually make it even harder for them to be engaged?

Henning

Absolutely. That is true. Our responses are counterintuitive, and more harmful than helpful. And we see this over and over again, and particularly during adolescence, I mean, the absolute worst thing you want to do during adolescence is stifle creativity. The brain is the most malleable, and positive reinforcement, positive supports, rehabilitative strategies, corrective engagement, ways of redirecting young people towards positive activities is the most effective during adolescence. So instead though, what we’re doing is we send them to juvenile detention facilities, and even juvenile prisons where it’s the opposite of creativity. In fact, it’s regimented routine activities so that more than anything you just reinforce negative behaviors among young people. So it is truly the worst thing that we can do. And we need to keep kids in school. The more you suspend a child, discipline a child, the more likely they’re going to drop out of school altogether and never go back. So they never become productive citizens, both in an economic sense and in a law-abiding sense. So we’re not doing ourselves any favors, either, in terms of public safety.

Robinson

Yeah. When I was growing up in Florida, I worked at the local teen court in Sarasota. I had a kind of revelation, a good experience that made me want to be a lawyer. It was a diversionary program in the teen court, and they were bringing in 16 to 17-year-old white kids who smoked pot, and they would get to do the diversionary program. The kids got to do this volunteer thing. Then, when Black children came in from the Black school in the city, they were younger. They were like 10 years old, and they’d been arrested. There was a 9-year-old girl who’d been arrested because she threw a tantrum in class and kicked her teacher. Okay, so you definitely shouldn’t kick your teacher. But this is something that was clearly, in all of the other schools, being dealt with administratively. If you kick your teacher, you go to the office, and then you have to write a note to your teacher saying, I’m sorry I kicked you. But in this school, she was dragged away in handcuffs, and then put into a court proceeding that is then going to occupy the next months of her life as a 9-year-old child. A 9-year-old child doesn’t even understand what a court is. How could we possibly think that this is helping this child? As you say, it happens all around the country. When a small Black child commits an offense that in a white school would be dealt with in the normal, regular, sane way that you would deal with a child misbehaving, the handcuffs come out.

Henning

Absolutely. And it’s just so sad. That story is so painful to contemplate, right? Taking a 9-year-old out in handcuffs is just so appalling. There are so many pieces to that. Black children do tend to be younger, it’s true. The racial disparities in arrest are even greater the younger the child is. So the essence of childhood is lost earlier and earlier for Black children. And, in fact, there is research showing that civilians and police officers often perceive Black children as older than they are—in fact, four and a half years older. There’s research by Dr. Phillip Atiba Goff and colleagues. Tamir Rice, for example, who was 12 years old, was seen as being 16 or 17 years old. But if a 16-year-old is being looked at like a 20 or 21-year-old, it really has profound impacts. And then think about how these young ages of 8 and 9 years are being perceived and treated. I assume you know about the report from ProPublica, about those children in Rutherford County, Tennessee, who were arrested—they were between the ages of 8 and 12—for a crime that did not even exist. The police officers came into their school and took them out. And what was so tragic about that when all the information came out was that these children were watching after school a pickup game of basketball. Little bitty children. Then there’s a little fight that breaks out. These children were watching the fight—they weren’t in the fight, but they were watching the fight. And so they got arrested for that. Again, little Black children who are 8 years old. When they got arrested, they were crying hysterically out of fear and terror. For example, in D.C. there was the story of a 10-year-old child who got placed in handcuffs and soiled his pants because he was so afraid. We would never ever think about treating white children this way, to be quite frank.

Robinson

Black children are perceived as being older but even sometimes are tried as adults and are thrust into adult facilities. We could get into all the true horrors of prison and what that could do to a child. Oftentimes the child is disciplined for disobedience or for not obeying the rules rather than the punishment being calculated towards the goal of the child doing well in school. Another case that comes to mind is a kid who’d been suspended from school, but he went back to school to get his homework from his locker. He was like, while I am suspended, I want to do my homework. This is a Black kid in middle school arrested for trespassing. They said, Oh, you were banned from the school. But he was like, I came back to get my homework. Now, a normal approach to that is to say, Good, glad you came back for your homework. You can actually use your suspension to do schoolwork. But as is often the case with police encounters, what the police detest most is any sign of defying police authority, which is punished incredibly harshly.

Henning

Yes. I actually wrote a chapter called “Contempt of Cop.”

Robinson

Oh, yes. Right.

Henning

It’s a play on a concept. I didn’t come up with it. But journalists have written about it. And they’re able to document the offenses across the country for which police officers arrest folks—especially young people, but it could be anyone—for disobedience or disregard of authority or showing disrespect to a police officer. And again, this really ties back to what we talked about earlier about adolescents. Adolescents are fairness fanatics. So you’ve got a kid who gets stopped by the police. They believe they’ve been stopped unfairly. So they speak out, and the officer doesn’t have any real reason to arrest them. There’s no drugs, there’s no gun, there’s no assault. Instead, the officer arrests them for these low level offenses like disorderly conduct or disturbing the peace. In some states, there’s a statute called disturbing schools, and folks across the country have been trying to advocate for those statutes to be removed, particularly as they relate to children. That’s one of the ways in which Black and Brown people are arrested for standing up for their rights. It’s similar to your story about perceived disobedience to some rule or authority. I told you to sit down, so you must sit down. We hear this all the time. People and police officers will say, Well, if you just obeyed, if you just did what I said, then I wouldn’t have had to beat you with my baton. Or I wouldn’t have had to arrest you. This ignores the extraordinary psychological trauma that’s associated with a false arrest or an illegal stop and frisk. We actually have rules in the country about when a police officer can stop you. And so any effort of a Black child to speak out is treated as absolute contempt and can lead to force.

Robinson

It’s very difficult for a child to accept something perceived as unfair. We know that kids say, but that’s not fair. That’s not fair. Children throw a tantrum if something’s not fair. And it’s actually a rather lovely quality of children, and they have this very deep sense of justice. And if you can’t offer them an explanation that is satisfactory as to why you’re doing something, it makes a child angry. That shows children to be really quite precocious reasoners. They want reasons for things; they want the world to make sense. They get frustrated and angry when the world doesn’t make sense; whereas as adults, we’re so worn down that we just go, Yeah, the world doesn’t make sense. You just gotta accept arbitrary positions of authority over you, and you’ve just got to be quiet, and that’s the way it is because you want to get along in the world. And that’s sad. There’s this spark of rebellious fire in children that we should admire and love about them.

Henning

Absolutely.

Robinson

You must have seen a lot of really bright and wonderful and curious young people who just get beaten down by this system and who just lose that spark of joy and delight. I mean, Eric has a happy ending. In the book, you do give some hope, but there are a number of really tragic cases of wonderful kids who are just subjected to this brutal, brutal system, and it’s really gonna destroy their souls.

Henning

Right. We should recognize this phenomenon is happening. I mean, we know enough now about children who are subjected, for example, to parental abuse and neglect, and what happens to them when they’re given limited opportunities. Now, imagine an entire society, which is manifested by the policing and criminalization of Black children. And when I talk about policing, I should point out that I’m not just talking about police in a blue uniform. I’m talking about all civilians who are afraid of Black children and treat them with fear and rejection, and who call the police on a Black child. Over time, that does real damage to the psyche of a Black child—their sense of hope, their sense of what they can achieve, and whether they should participate in mainstream society. We should not be surprised by that, right? You can’t beat a dog until they’re down, and then expect them to get up, and children aren’t dogs. So you just can’t expect them to get back up without some support, and so I do want to offer a word of hope for all the children, which is what one of my psychologist friends said to me. It’s that every single child deserves one irrationally caring adult, and children do better with a team of irrationally caring adults. And that we can shift that tide, for one thing, by treating children like children—and especially Black and Brown children who are disproportionately adultified, for lack of a better word—so that when children make mistakes, what it means to be an irrationally caring adult, is to recognize that children will make mistakes, they will do things that we don’t approve of, but we will still stand by them, we will offer them guidance, and we will offer them redirection. And even when there are more serious offenses, when there has been criminal behavior, we show the same grace and tolerance to the Black children as we would to a white child. So that means mental health supports, that means vocational opportunities, that means taking advantage of what is evidence based best practices for dealing with children who have been engaged in violence. There are programmatic frameworks for dealing with young people. There are strategies for teaching conflict resolution to young people. So yeah, there are ways in which we can treat children with grace and give them hope, and help them get to a place of resilience.

Robinson

Yes. I wanted to conclude by asking you about the programmatic alternative to the dysfunction you see. In many ways, it is simple and straightforward, which is that once you begin from the premise that Black children have equal humanity and deserve the same things—you cite some of the “criming while white” cases. Or if we think about teenagers like Brock Turner or Kyle Rittenhouse, who had judges draw attention to the fact that they are teenagers and teenagers are impulsive, then it really is just a matter of applying the same set of standards equally so that we recognize what a child is and what a child deserves and that that doesn’t vary by race.

Henning

Yes, that’s it. You nailed it. That’s it. It’s applying those principles that we know. We have more research on the adolescent brain and how it works and how to rehabilitate it and how to nurture it to its best place—from adolescence to adulthood—than we ever have. And it is about applying those same principles to Black children as we do to white children. Your examples are spot on. Kyle Rittenhouse was just such a quintessential example of adolescent behavior. He tracked over state lines with a rifle attached across his body with minimal experience with handling a weapon. He had this hunting license, but he’s still a kid. He’s got no level of expertise. That’s why, you know, this situation went so awry so quickly. It’s irrational. It’s not thoughtful. He wasn’t thinking through the consequences. What really struck me about the Rittenhouse case is how his mother almost pleaded with the public to see him, or pleaded with the officers, to see him as a child. She was quite distraught when the police told her that her son would be tried as an adult. Kyle Rittenhouse cried as if he was a child. And so there was a sense that this was a teenager. And you’re absolutely right that when we see Black children coming in on serious cases—even without a death involved—as you mentioned earlier, they are absolutely transferred into adult court, not given the benefit and the second chance, not given mental health support and the like. So we really just need to apply the same principles that we would apply to any adolescent who either makes a mistake or who just does something very stupid, irrational, and poorly conceived.

Robinson

A number of my progressive comrades saw the Rittenhouse case and wanted the kid sent to prison because he was a murderer and he went to a Black Lives Matter protests and killed two people. But there’s a different reaction which says, Okay, well, we can be angry at him or we could take our anger in a different direction. Why don’t we ensure that everyone gets the kind of mercy that someone like Rittenhouse gets? I mean, he got a lot of understanding. And yes, that’s deeply unfair, because not everyone gets that level of understanding. But why don’t we expand our circle of empathy and exclude the possibility of sending a minor to an adult prison for decades from the range of possible solutions to social harm?

Henning

Absolutely. It’s not only empathy, but also due process. Let’s start there right at the beginning. He got a fair trial. So notice what I’m doing. I’m taking race and politics out of the conversation about Rittenhouse for the moment. Truly it is due process as we envision it. It was an opportunity to confront the witnesses and the like. You think about Tamir Rice, who had a toy gun that he was playing with—not an assault rifle strapped around his body. Tamir Rice didn’t kill anybody. But within less than three seconds he was shot down by police. That’s the difference. Kyle Rittenhouse got due process, and Tamir Rice got killed. Forget empathy on the back end for Tamir Rice. Even when Kyle Rittenhouse is the clear perpetrator—he had a weapon with live ammo that could kill people and he did kill people—he still got mercy.

Robinson

Well, Professor Kristin Henning, thank you so much for this fascinating and very important conversation. The book is The Rage of Innocence: How America Criminalizes Black Youth, available from Pantheon books.

Henning

Thank you again for having me. I appreciate your attention to this conversation.