How Did the COVID-19 Pandemic Start?

Dr. Alina Chan has been one of the most prominent commentators on the origins of COVID-19. Here, she explains why the binary of “natural origin” versus “lab leak” is misleading and simplistic.

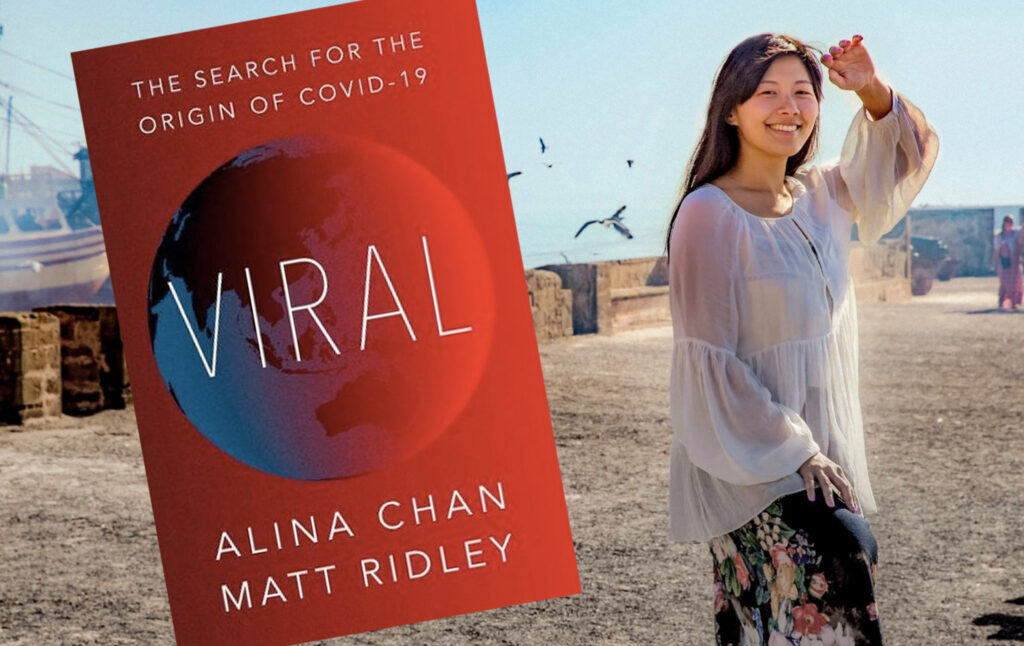

Dr. Alina Chan is a molecular biologist and a postdoctoral fellow at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. She is the co-author of the new book, Viral: The Search for the Origin of COVID-19. Dr. Chan has developed a reputation as one of the foremost commentators on the debate over the origins of the COVID pandemic, and was one of the people most instrumental in forcing a greater discussion of the possibility that the virus may have emerged from a lab in China. She recently spoke with Current Affairs editor in chief Nathan J. Robinson on an episode of the Current Affairs podcast. The following transcript has been lightly edited for grammar and clarity.

Robinson

When you read articles on this topic, they talk about the “hypothesis of a zoonotic spillover” versus a “lab leak.” One of the values of your work has been to try to make clear the different possibilities of the origin of the virus and what they really mean. What exactly are the alternatives here that are being considered for the origins of COVID-19?

Chan

This topic is really complicated. And one of the biggest challenges is that, because it’s so complicated, people like to talk about it in really overly simplified terms. So when we’re talking about “natural spillover,” immediately, most people will think about bats or the wildlife trade, such as pangolins, civet cats, raccoon dogs being traded and eaten. And this is certainly still a plausible way that COVID-19 could have emerged, that it was a virus inside a bat or another animal in the wildlife trade. The animal was caught, handled, consumed, and, in that process, a person was infected and started the pandemic.

But for a lab-based scenario, it’s actually quite complicated. It’s not just a Frankenstein creation in the lab that escapes and causes a pandemic. It involves a whole range of research activities, including collecting the viruses in the wild. There are thousands of researchers going out into the wild collecting viruses from not just bats but even from the wild animals in the animal trade. They also collect samples from humans; they look specifically for people who are sick. And they search for those viruses. And they bring them back to the lab to study them. So by this pathway, there’s quite a bit of overlap with the wildlife trade, right? So researchers are collecting the viruses from these animals in the wildlife trade. But some people classify this as a research-related origin, because without the research activity, those viruses would never have been transported into a city like Wuhan, for example, and allowed to start an outbreak.

Robinson

So much of this discussion has become so political with Donald Trump and the Republicans being associated with the lab leak theory. And of course, Democrats are vigorously pushing back on it in part because I think there is a fear that the lab leak theory comes not out of science, but out of a desire to inflame tensions with China. So, often in the discourse, it’s talked about like the two poles of the political system, with the lab leak on one side and the natural spillover on the other. But what you were just saying was that you could have a natural spillover that is associated with a lab. If a researcher went to a cave and was studying bats and got infected, this would be both natural and lab-based, right?

Chan

Yes, that’s right. And the reason why I personally choose to identify that pathway as a research-related pathway is because the strategies to prevent outbreaks stemming from these activities are different. So even though it starts with a bat and a cave, if you want to prevent that outbreak, you have to either stop tourists and farmers and cave miners from going into these places, or you have to stop the researchers from going into these caves and bringing the viruses back to the city. So I classified the pathway based on the mitigation strategy. So, again, with the research-related pathway, you’ve got all these activities from collecting and bringing the virus back to the lab, growing them up, manipulating the viruses, studying them in different cells—bat cells, human cells, raccoon dog cells, even, if you have them—growing them up in animals, animal models of disease like civet cats, ferrets, and even humanized mice. So it runs the whole gamut of research activities that we have to look at and see what the risks are of these activities resulting in a lab escape.

Robinson

It’s often said that the virus has been manipulated artificially in the lab. And there’s all this controversy over what is called “gain of function” research. And this was what the big clash between Senator Rand Paul and Anthony Fauci was about. But that’s not the only possibility. As you say, there are lots of different ways in which a researcher could come into contact with a virus. So you said that we’re talking about different mitigation strategies for different pathways. Lay out why it’s important. We know that it’s important to discover the origins of this virus, obviously, so we can prevent the next pandemic. But what are the implications of one hypothesis versus another being true?

Chan

The natural spillover hypothesis is a story we’ve been told thousands of times. It’s a mantra that scientists and nonscientists have, the idea that the ways that human beings interact with nature are inappropriate, that we’re invading their habitat, we’re poaching animals and carrying them thousands of kilometers to different places. At the same time, we’re transferring pathogens from remote natural habitat out into urban centers. That’s real. I’m not denying that at all. And there should definitely be strategies adopted more rigorously to stop these activities from happening. But as we move into the 2020s, there are so many new technologies at our fingertips to manipulate viruses to study and enhance them in the lab, unfortunately. And so we have to start taking into account new risks and new sources of outbreaks. To not take steps to address this risk would be to put millions of lives at risk in the future. So the old risks are real, and so are the new risks.

Robinson

One of the things that struck me when I started reading and researching this is what’s at stake for human safety if it turns out to be from the wildlife trade. Obviously, that implies the wildlife trade is very dangerous and we ought to be more careful. And if it turns out to be the result of an experiment to increase the infectiousness of viruses, that also implies that there’s something that’s terribly unsafe about that kind of research. But it’s also the case, isn’t it, that there’s something at stake for peoples’ stories about the world, right? I think that’s one of the reasons it’s been so difficult to have this conversation. You’re describing the scientific stakes and the stakes for prevention strategies. But there’s more at stake. Democrats are now very invested in Anthony Fauci. Republicans obviously tend to make China seem nefarious. And it’s all wrapped up in people wanting one explanation to be true because it fits with their narrative. If you have the EcoHealth Alliance—which we’ll get into—their guy was saying that he’s been warning for years about the wildlife trade. So if this is the correct explanation, it proves right someone’s story about the world.

Chan

Yes, and if it’s wrong, it completely destroys the narrative of how things work in this universe. So even though scientists had completely good intentions—they were trying to prevent the next pandemic, yet that approach led to this pandemic—that has unparalleled consequences for the scientists doing this type of work for the scientific community, and for anyone who shuts down discourse on a possible lab origin of COVID-19.

Robinson

A lot of people are very invested in it now. You mentioned researchers collecting viruses in the wild. I think that’s pretty clear to people. But when we’re talking about the possibility that the virus was somehow enhanced, what is going on? What is this? What is the kind of research that we would be talking about that would involve that?

Chan

When scientists collect viruses from nature—from animals or even other human beings in remote areas—the first thing they want to do is figure out what they are dealing with. So they take the virus, they sequence it, they take a look at this completely new and mysterious sequence, and they try to make sense of it. But to really understand how these viruses work, they will try to grow them in cells, they will try to infect different cells with them, or even animals with them. If they cannot grow the virus in the lab, they will take parts of it that they can put into other viruses that they have in the lab and try to study these parts in the lab. And so this research is pretty routine. I’d say it’s not something that’s generally viewed as extremely dangerous or risky. But there is a different category of research, which is called “gain of function research of concern,” where there’s a reasonable expectation that an outcome could be the enhancement of that pathogen. So that pathogen could be made—accidentally or unintentionally—to be more transmissible amongst humans or mammals, or to be more dangerous, more severe, causing disease. So the challenge here, though, is separating what is “gain of function research of concern” versus what is just regular research or “gain of function research.” So the arguments have been about what crosses that boundary into “gain of function research of concern.”

Robinson

As I understand it, this research is not necessarily a nefarious thing that is going on by people who are trying to create bioweapons. It’s mainstream virus researchers who are studying viruses in ways that others in the community have warned are more dangerous, almost, than the thing that they’re trying to prevent. And this has been a debate for years over whether some of this research is extremely dangerous, is that right?

Chan

Yes. So when I started looking into the origin of COVID-19, I was not aware of this really toxic kind of argument about “gain of function research of concern.” This argument has been going on for more than a decade. And there are scientists on both sides of the issue with equally strong opinions. On the one hand, you’ve got scientists who didn’t think that the risk of a lab-enhanced pathogen escaping was that high. So I think they really underestimated the scenario where one day, a lab somewhere out here in the world, working with viruses in a way that is less than safe, would result in a pandemic. So that’s that side of it. And they argued that the risks were worth taking in order to learn more about the pathogens in nature. And on the other hand, you’ve got scientists who believe that we shouldn’t be so reckless, because even though the risk, the probability is low, just a single accident has the potential to take millions of lives. And so they argue that the risks are not worth taking. And so this debate has been ongoing for years, long before I even started looking into COVID-19.

Robinson

That’s another instance in which someone’s gonna be proven right, and someone’s gonna be proven wrong. So it’s the argument that some people have been making half their lives. So it’s all wrapped up in their identity. So, a lot of what you’ve done is try to determine what is the evidence that we know. Can we start with the most important hard facts that we do know for sure that bear on what possibly is true? What do you think is most important for people to bear in mind about what we do know?

Chan

What we do know for sure is that this pandemic could have started from a lab or research activity, whether or not it did start from research activity. But I’d say that we know now that a pandemic can start from a lab. And so we don’t need to wait till we find the actual origin of COVID-19 in order to start implementing regulation, and preventative measures, to make sure that in the next 5-10 years, we don’t have another one of these pandemics in a city where there’s a lab dealing with exactly that type of virus. So, in terms of the available evidence, right now, I’d say that there’s no definitive evidence for either natural research-related or lab origin scenarios. But there is a lot of circumstantial evidence piling up on both sides. For the moment, I’d say that I lean more towards a lab origin, because there have been so many documents recently leaked, or obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, showing that there was a large volume of pathogen research being conducted in Wuhan city in the years leading up to the emergence of COVID-19. So right now, I don’t think that we should be placing our bets. I think that we should be calling for more information. And there are so many routes of inquiry that are unfortunately blocked to us right now. A lot of it is inside China. But there are many things we can look into outside of China.

Robinson

It’s interesting that we might in fact face an outcome in which it turns out that risky research was in fact being done on bat coronaviruses in Wuhan, it didn’t cause this pandemic, but now we know what a pandemic from a novel coronavirus can be like—that is to say, it’s terrible. So either way, regardless of the precise facts, we really need a lot more scrutiny into the kind of research that is being done, now that we have firsthand experiences with the consequences of a pandemic coming from this type of virus.

Chan

Yes. I don’t judge the decisions that were made pre-COVID using post-COVID hindsight. I have tried to be as generous as I can in looking back on this debate on “gain of function research of concern.” I don’t think anyone really thought, in the past, that experimenting with a bat coronavirus—fresh from bats—would lead to a virus with the potential to cause a human pandemic. Okay, maybe not no one. But I’d say that the number of scientists who believed that could happen were in the minority. But post-COVID, now we know that—some people are saying that a virus directly from a bat could cause a human pandemic. So I think now we have a heightened sense of danger when dealing with novel coronaviruses.

Robinson

One of the things that stuck out to me from when I was researching this—first to write an article I did a while back, and then, of course, when I was reading your book—is that we do know that there is a lot about the Wuhan Institute of Virology to be concerned about. The investigation of the Wuhan Institute of Virology by the World Health Organization was really compromised by a severe conflict of interest by Peter Daszak, who had worked with the Institute on a project. We do know that they were working with coronaviruses at a lower level of safety than one would be comfortable with. There are facts that should make us concerned about what was going on at that Institute in particular.

Chan

I’d say that the information about the type of research—and the level of safety that that research was done at—trickled out very slowly throughout 2020. So if you look back at early 2020, I think that the picture that people had was that there was this extremely high biosafety lab, BSL-4, the top biosafety level laboratory in Wuhan. So there was speculation about bioweapons and that maybe a virus being experimented with at BSL-4, the highest level, could lead to a pandemic. A lot of experts pushed back because they thought that BSL-4 was so high a level that barely anything could ever escape. But in 2020 and by early and mid-2021, more information started to come out. And we discovered that a lot of this live coronavirus research had been done at a very low level of safety, at BSL-2 level. So I know that some experts have compared this to a dental office. I’d say it’s quite different, but it still doesn’t protect you from an airborne virus. BLS-2 cannot protect you from a respiratory virus, and many virologists will agree that this is not appropriate. You’re not supposed to work with SARS-like viruses in a BSL-2 lab.

Robinson

How important in the assessment is the coincidence of the fact that the leading research on novel bat-borne coronaviruses—and the closest known relatives of COVID—were being done in the city where the pandemic was first traced to? How much weight do you put on that particular coincidence?

Chan

I think the weight that different experts put on this coincidence differs based on their priors. So you’ve got some very pro-natural-origins experts who spent their entire lives investigating naturally emerging viruses. So they’ve spent years in markets and bat caves, digging around in really remote areas, looking for naturally emerging viruses. So when they see this happen again, even though it’s in the city where there’s a lab looking at that virus, they’re like, Oh, it just must be from the Huanan seafood market where there was an early cluster of cases. For them, it must be. On the other hand, you’ve got people a bit more removed from this zoonotic virus work. And they see that this virus, instead of emerging in the natural spillover zone of SARS viruses in South China or Southeast Asia, emerges in central China more than a thousand miles away from the spillover zone. And when they see that they think, what are the odds of a virus like this emerging in Wuhan City? So there are quite a few factors to take into consideration. One, Wuhan is a very central hub in China. There’s a lot of traffic passing through there. Two, there is still a bit of wildlife trade happening in Wuhan City. It’s not a booming wildlife trade like you see in Southeast Asia and South China. But there are still some animals being trafficked, although no bats or pangolins were ever found to be trafficked around there. But on the other hand, you’ve got this lab, which is collecting and creating the largest collection of diverse, novel SARS-like viruses. We have no insight as to what viruses they’ve found over the years. We barely know what they’re doing in the lab there. They are doing some fairly risky experiments. One of the leaked documents showed that in early 2018, they had a roadmap for inserting novel genetic modifications into novel SARS-like viruses. So when you look at that, and you see a novel SARS-like coronavirus with a novel genetic feature emerge in the city where scientists are doing this type of work, I think the coincidence is even more coincidental. It almost seems like it would be the most cruel irony that a lab seeking to prevent such a pandemic had this happening in their backyard, to borrow the words of Robin Jacobson.

Robinson

It would be a spectacular coincidence. There was an article recently in Science that’s called “Why many scientists say it’s unlikely that COVID originated from a lab leak.” And there’s a sentence that says, “At its core, the lab-origin hypothesis rests on proximity. A novel coronavirus, genetically linked to bats, surfaced in a city that’s home to the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV), which has long specialized in studying bat coronaviruses, and two smaller labs that also handle those viruses.” Would you say the case rests on the proximity?

Chan

I’d say that comparing the categories of evidence between natural and lab-based origins, they’re pretty even. But it’s true that the proximity factor favors the lab leak hypothesis. So if you look at historical evidence, precedents of natural viruses versus those that have escaped from labs, there’s pretty strong cases for both natural and lab. So even the first SARS virus, after being studied in labs, leaked at least four times from labs as high as even a BSL-4 lab. So there’s pretty strong historical evidence for both natural and lab origin viruses. If you look at plausibility—is there a pathway for this to happen? Yes, there was wildlife being sold in Wuhan. So a natural spillover is still on the table. But there’s also that lab that’s doing a large volume of research to the point that it’s not surprising to me that one day, over 10 years of doing this work, some of the pathogens would escape, especially if they were doing work in BSL-2. Not BSL-4. You know, if you drop something on the floor, everyone’s immediately exposed to an airborne virus.

Robinson

Is that how easy it is? And what is the kind of scenario in which a virus would escape from a lab in those conditions? I mean, what are we talking about when we’re talking about an escape?

Chan

Matt Ridley and I get into this in detail in the book. There’s a whole chapter on that leak. And I really like that chapter because it brings a nonscientist into the lab. It helps you see what it’s like working in the lab, and how easy it is for a single accident to result in a lab escape, unfortunately. So the good thing is that not too many labs around the world work with human pathogens or pathogens that can cause pandemics. The bad thing is that there’s a really low level of transparency. Very few lab-acquired infections, accidents, are reported and tracked and recorded and made public. But if you look at those that are in the public record, you’ll see that it is so easy to get infected by a virus in the lab, especially if you’re working with them at a lower than expected biosafety level. But let’s go through the SARS-1 cases. For example, in one case, a researcher was working at BSL-4, the highest biosafety level. But in a single moment, he made a human error. He decided to take off his protective equipment and clean up a mess in the back of the lab. And because of that, he got infected with SARS. So even though the whole facility and the protocol were solid and could protect you against a SARS virus, human error led to him being infected. There are so many ways for this to happen. You don’t need to be growing buckets of viruses. It could just be a very small experiment. A single error can lead to infection.

Robinson

Separate from the politics, one reason it is difficult for people to contemplate the lab leak—I call it the lab accident theory—is because if nature did this, well, you know, we can’t control nature, you know, that’s the wild, it’s the wilderness. Yes, we came too close to the uncontrollable wilderness surrounding us and maybe we should be careful. But it’s very hard to accept the almost absurdity and human tragedy and folly of the fact that we were trying to stop a virus and some small mistake killed millions of people. But I think humans often overestimate how sophisticated we are, despite our advances, and assume that scientists know what they’re doing. And one of the things that comes across in your lab leak chapter is that researchers do not always know what they’re doing. I mean, they know what they’re doing to some degree, but they make elementary oversights.

Chan

Researchers are humans, too. We make errors; we have accidents. We have bad days. We have moments where we lose focus, and accidents can happen. So even machines break down. There’s no printer or fax machine that hasn’t broken down before, right? Unless you’ve never used it. It’s just incredible to have this illusion that scientists never make mistakes, never violate protocol, that they’re always in control. That can’t be. What we can have control over is, at least, doing this type of research in a much safer way. So first of all, increasing transparency, making sure that other people are aware that you’re working with these viruses so that they can keep a watch out for you. The second thing is moving them out of metropolitan cities where a single flight can take you to any tourist destination in the world. Why is this the case? Why are we working with pandemic pathogens in the middle of cities where you can take a plane from there to anywhere? This doesn’t make any sense to me. And there are many steps we can take. We shouldn’t see scientists as gods, but we shouldn’t see them as demons, either. So I think the problem here is that people don’t see scientists as humans, people in the middle of this mess, struggling every day to make sense of it as well, and not knowing what exactly they’re doing. Scientists are not evil people who are deliberately doing this dangerous research to cause pandemics.

Robinson

I think it would be very, very difficult for someone who had been engaging in this research to accept the possibility that they might have contributed to something so horrible. One of the points that you raised is that one of the reasons that we don’t have good answers is that there really has not been much transparency from the lab. And in fact, there has been what I think can only be described as the covering up of important data that is useful to assessing and answering this question definitively. Is that right?

Chan

Yes. Lab accidents happen everywhere around the world. This is not a culturally specific thing. I mean, in the U.S. alone, accidents happened an estimated four times a week in 2019. Dangerous pathogens were exposed in some way. They didn’t result in infections, but in some way they had breached their safety protocol or containment. So that’s in the U.S. alone, four times a week in 2019. If you look at the whole world, there must be so many of these accidents happening. But not all of them lead to outbreaks, to sustained transmission of the pathogen in the human population. And everyone who does this work, I suspect, does not think that they are going to be the one starting the next pandemic. They’re always like, It’s another lab in a different country that’s setting this pandemic. It’s not me, it’s not my team. But when it does happen to you, what do you do at that point, right? And so I think at that point, it becomes a human decision, like, do I admit to it now and pay the penalty? Or do I wait and see what happens? And if you wait, what if the pandemic gets bigger and bigger, and at some point, you have a million people infected, and at that point, you may not want to say anything at all, because you cannot shoulder that burden. So I’d say that, at least from someone looking from the outside in to people doing the SARS pathogen research, we should not be putting this kind of burden on researchers. To have the risk of one person alone causing an accident, and suddenly 100 million people get infected—no one should be doing this type of research.

Robinson

You begin the book with the story of the miners who got infected in 2012 or 2013 with a very similar virus that was studied at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. And I think we know that the virus’s closest known relative was housed at the Institute. But one of the things I don’t quite understand—because I don’t understand the science and you do—is, how close a resemblance does something have to be to COVID-19 for that resemblance to be significant? The number 96% similar doesn’t really mean anything to me, because I don’t know what lies in that 4%. And whether it’s 96% and not 100%. So what is the significance of the evidence that we do have about things that were similar to COVID being studied at the Wuhan Institute?

Chan

Up until recently, the closest virus relative to SARS-CoV-2 was collected from this Mojiang mine where six miners had sickened with a mysterious pneumonia and half of them died from it. This was a 96.2% match to SARS-CoV-2, not close enough for it to be considered a precursor, or even the direct ancestor. But quite close within the ballpark that you wonder whether the scientists collecting viruses from this area had found a direct ancestor or precursor to SARS-CoV-2. So we don’t know that. But…coming from this mine where people had sickened, possibly from a bat SARS-like virus, it does raise the question: over the past 10-20 years that this research has been happening, have scientists collected the ancestor of SARS-CoV-2 and just not told anyone about it? But for a virus to be seen as a direct ancestor, we are looking for something like a 99% match or even higher, so anything above 99% would be very interesting. Recently, there was another close relative found at 96.8% match; it was found in Laos. So just across the border from Yunnan province where this mine is located. So we know that in that area, where the mine is, and possibly down into Laos, there are many viruses quite similar to SARS-CoV-2.

Robinson

I want to ask you about the investigation so far. One of the things that is rather striking is that the World Health Organization sent a team to Wuhan that investigated the market and did very briefly visit the Wuhan Institute of Virology. They put out a report. I read it. It basically said that a lab origin was unlikely, and it put the emphasis on the quote natural spillover. What is it about that World Health Organization report, its methods, its conclusions, that you disagree with?

Chan

This is in another chapter in the book, which I think is really exciting. And so we described the China WHO joint study. They don’t even call themselves an investigation because they didn’t have the mandate, or even the plan, to investigate. So all they could do was send a small team of international experts to China to meet the other half of the team, which was all Chinese scientists, to go over the analysis already done by the Chinese scientists. So the international experts had zero access to any of the full datasets, any of the primary data, used to inform this analysis, and then went on a tour around the city. And at the end of those two weeks of touring, they signed off on the report that said that a lab leak was extremely unlikely, but they also thought that a cold chain frozen food origin of SARS-CoV-2 was possible. So they ranked a scenario where a frozen block of meat gives a human being the virus and causes the pandemic as more likely than a lab origin. So I think that this investigation was compromised at several levels. So first of all, the team membership had to be approved by China, and half of the team is from China. They didn’t have access to data. They didn’t have control over where they were taken to see anything. And so a lot of extremely basic follow-up for an investigation was not even conducted by China, apparently. So they didn’t contact trace the earliest cases—that’s still shocking to me. And they didn’t test any blood banks to check samples of patients in Wuhan to see when the virus had first emerged in the city. They did not go to the most upstream sources of animals, the seafood market, so they didn’t even pursue the market hypothesis in China. They didn’t go and check and test animals on the farms that had sent animals to hunt. There are so many things that were not done, despite a killer virus emerging in central China—where it’s not supposed to be found—and causing this massive pandemic. So I think that this study was a complete failure. I don’t know how else to say it. There’s nothing redeemable about it.

Robinson

I was shocked by the degree of credulity with which it treated the assertions by the lab of its safety methods. I just could not get over the fact that the U.S. member of the WHO team is this guy, Peter Daszak, who was involved with the very bat coronavirus research at the Wuhan Institute that if we were talking about a lab accident, would be responsible. So it was like having a potential suspect to lead the prosecution in the criminal investigation team. It was totally bizarre. They appeared to just go and ask the lab, “Did you follow safety precautions?” Yep. Daszak said, at one point, “Well, we asked them, and they said it was safe.”

Chan

Yeah. I remember the day when I saw the list of international experts that the WHO had recruited for this mission. And I was in disbelief. I think I was just shocked to see Peter Daszak’s name on this list, because he stands to lose so much if this comes from a lab. So if this virus comes from a lab that he had funded in Wuhan and has been a longtime collaborator with, he could lose everything. So his legacy gone, future funding gone, reputation gone, even personal safety might be gone. So how can you ask him to lead an investigation of a possible lab origin of COVID-19? When I saw that list, I was like, alright, let’s just see what happens. How bad could it be? Well, they showed us how bad it could be. So the study conducted in Wuhan was, I think, pushing the boundaries of what scientists could find acceptable. So, as you said, they went to the Wuhan lab for a few hours, and then they got to tour the BSL-4 facility, even though the work had been all done outside of BSL-4 at lower biosafety levels. And then they sat down in a conference room and they all asked each other, “Did this come from the lab?” And, of course, the people from Wuhan said it didn’t come from the lab. It came from frozen pangolins or something. And then they voted. So apparently the process of determining whether a lab origin was likely or not was for everyone in that room to vote on it together. So you’ve got half the team, as Chinese scientists, and the other half of the team includes this man and other people who are conflicted, because they’re involved in virus hunting. That was not a scientific process to me. It doesn’t look scientific at all.

Robinson

I noticed that Daszak is quoted as a commentator everywhere. He is quoted as an authoritative expert, and really aggressive in attacking anyone who suggests that it was not of natural spillover through these markets. The discourse around this has been very, very poisonous and the opposite of what you’d want in a neutral scientific investigation, isn’t it?

Chan

Yes. And I’m afraid that the WHO is repeating this mistake with its new SAGO committee. The WHO is now convening a new committee to advise future outbreak investigations, origin investigations. And for some reason, they decided to put six out of 10 of the original study members back onto this new team. So instead of starting with a fresh slate, with no conflicts of interest, for some reason, the WHO decided to go back and take most of the old team that was built and put them on this new team. I don’t think that they have learned from their mistakes. I think that they’ve once again included several members who have called the lab origin hypothesis a conspiracy theory, who have very strong competing interests, like some of them are longtime collaborators of the EcoHealth Alliance, where Peter Daszak is the president. So I don’t understand why the WHO hasn’t tried to do the right thing.

Robinson

The idea that it is a conspiracy theory is very frustrating, because an accident is the opposite of a conspiracy. An accident doesn’t require anyone to plot with anyone else. I don’t want to ask you to speculate, but if this was a genuine accident, why are the Chinese government and the WHO and all these people so very, very heavily invested in trying to discredit that theory?

Chan

This is a question I’ve asked myself quite a bit since the beginning of the pandemic. Why is the lab accident so much more dangerous than a wildlife trade accident? Because either way, it’s unintended. Either way, it’s still a pandemic. The virus is still killing people. So I don’t understand why if it came from a researcher, or from a research accident, that suddenly the whole world needs to be in chaos. Whereas if it came from a market, then that’s like, oh, no big deal. Let’s just go back to daily life, just keep trading animals, nobody cares. Let’s just wait for the next pandemic to come from the market like nobody cares. So I think that somehow the public response and the response from leadership doesn’t make any sense to me. But I suspect that a lot of the reasons why one might want to cover up a lab origin is because of this extremist response to a lab accident. So a lot of people are afraid that if it is found that this virus came from a lab that there is going to be a tsunami of anti-science people, that a lot of people will take down scientists and refuse vaccines, that kind of thing. Some people fear that if it’s found to be from a lab, no one will trust scientists anymore. And everyone was thinking about bioweapons and dual use research and pandemics and things like that. So I think a lot of the reasons why one might try to cover up a lab origin is that they fear this enormous backlash.

Robinson

Yeah. And the problem is that if you get so invested in defending that story, and if it turns out that it is in fact from a lab, you get the same backlash against scientists because you’ve actually proven that…

Chan

Maybe much worse backlash because people have seen that you have covered it up or refused to allow a credible investigation.

Robinson

Right. That does make sense. I want to just read to you from a couple of critical articles that suggest far more that the natural origin—again, I find myself slipping into “natural origin” which is very imprecise because it’s a “natural origin” even if you follow the research pathway, as we described earlier. What term do you use to describe the market wildlife hypothesis?

Chan

I also call it a natural origin.

Robinson

Is it natural versus research, that we consider research the opposite of natural here?

Chan

I think it’s problematic that people see it as opposite ends when it’s actually a spectrum.

Robinson

Right.

Chan

Some people can rule out the extreme end of a lab origin, which is a bioweapon. But there are so many things blending into natural origins that you can’t use the same approach to rule out all of these intermediary pathways.

Robinson

Yeah. A researcher going to a bat cave and getting infected is natural in pretty much every sense. The Los Angeles Times has an article stating that “New evidence undermines the COVID lab leak theory, but the press keeps pushing it.” It says there’s mounting evidence that it reached humans through natural pathways. It says that “the idea that the virus escaped from a lab is being treated credulously, ignoring the latest scientific findings supporting the theory that the virus’s origin can be found in the animal kingdom, which is accepted by the preponderance of experts in virology.” It says “a paper posted online this month by researchers in France reports three viruses were found in bats living in caves in Northern Laos with features very similar. Nature says these viruses are more similar to SARS-CoV-2 than any known viruses. Another paper reports on viruses in rats with similar features.” And it says that “given the idea that a laboratory leak would find its way to the very place where you’d expect to find zoonotic transmission, that is to say a wet market, is quite unlikely.” That’s a professor at UC San Diego’s Medical School. And a virologist at Tulane, Robert Garry, has said that “the new findings are a dagger into the heart”—again, the rhetoric around all this is ridiculous—“a dagger into the heart of the lab leak hypothesis,” and says there’s a new critical review of virological findings concluding there is no evidence that SARS-CoV-2 had a laboratory origin. So that’s then finally the Los Angeles Times. But I quoted you earlier from this article in Science about why many scientists say it’s unlikely that there was a lab leak. What is your response to these?

Chan

This is why I really think that we should have more events where scientists on different sides of the issue debate each other live. The problem here is miscommunication, or maybe over-exaggeration of what novel findings mean, for the origins of COVID, for example. So this idea that we found more close relatives of SARS-CoV-2 in nature, and some people interpreting that as evidence for natural origin—I think it’s a fundamental misunderstanding of how pathogens escape from labs. So if you find more SARS-like viruses in nature, it still just means that these viruses have been collected by researchers too, right? So it’s not that researchers magically create viruses you’ve never seen before and never found in nature in the lab. No, they use pieces that they find in nature, and they put together viruses in the lab. So finding natural viruses that are closely related to SARS-CoV-2 doesn’t tell us how a bat virus got to Wuhan. It just tells us that there are lots of bat viruses or SARS-CoV-2-like viruses. And so the question is, how did those bat SARS-CoV-2-like viruses make their way to Wuhan? Was it through the wildlife trade? Or was it collected by a researcher? So that really is an important point to communicate to the public. So I would love to debate Robert Garry. Get him one-on-one with me, and we will talk it out live on the show. I’d love to do that.

Robinson

Yes. It should be pointed out, by the way, that Alina did ask me beforehand specifically to bring on someone who disagreed so she could debate them. I declined because I thought that I was a critical enough questioner myself, but in case anyone thinks that Dr. Chan chose to shy away from confrontation, she actually did ask me to have an opponent on. There’s so much here that we’ve really just scratched the surface. People should pick up the book Viral: The Search for the Origin of COVID-19, co-authored by Matt Ridley. Dr. Chan, thank you so much for talking to me and explaining all of these things that I don’t understand in terms that I can understand.

Chan

It was really great talking. I really enjoyed this.