Why Leftists Should Embrace Our Proud History, from Thomas Paine to the New Deal

Historian Harvey J. Kaye on why we need to do more than just “debunk” nationalist myths. We also need to tell great historical stories of our own.

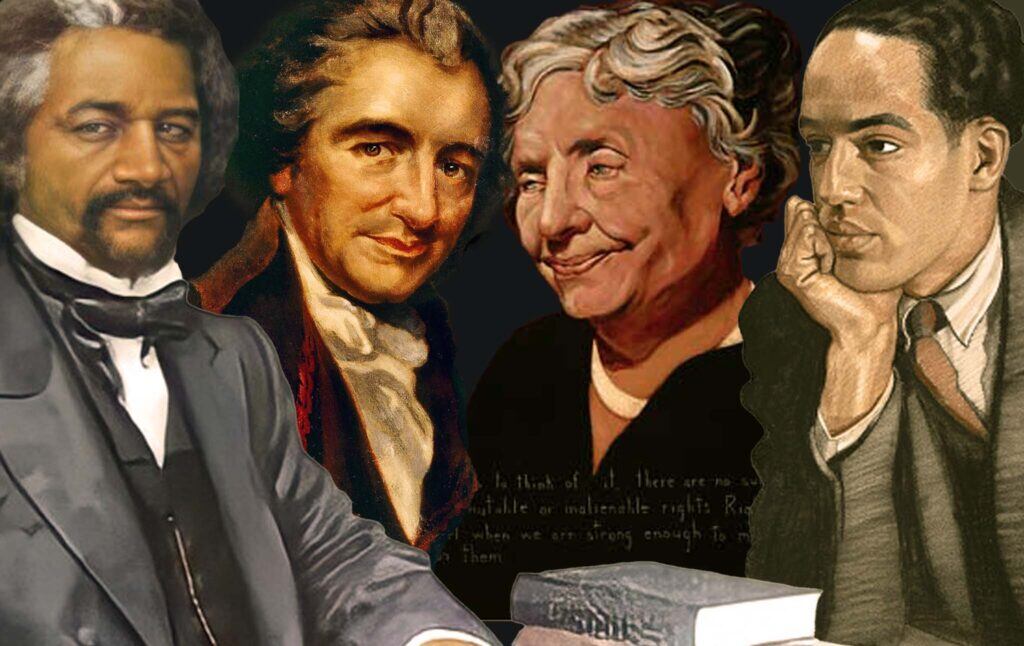

Historian Harvey J. Kaye has long argued that leftists are too negative about American history, and that our focus on its horrors and miseries risks downplaying the other side of the story: the great radicals in every generation who have fought, and often died, to make the country better, and whose legacy (and unfulfilled mission) we inherit. History is a rich source of inspiration and we have a great deal to gain by studying and learning from the inspiring figures who challenged the unjust social systems of their time, under even more trying conditions than we face today. Kaye recently joined us on the Current Affairs podcast to discuss his work.

Kaye is professor of Democracy and Justice Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay. He is the author of a number of books, including Thomas Paine and the Promise of America, The Fight for the Four Freedoms: What Made FDR and the Greatest Generation Truly Great, Why Do Ruling Classes Fear History? and most recently the book Take Hold of Our History: Make America Radical Again. The new book features a blurb from legendary TV producer Norman Lear, creator of All in the Family, who says “no one has ever loved a nation more or spanked it harder for straying from its premise than Harvey Kaye.”

The following transcript has been lightly edited for grammar and clarity.

Robinson

I love that Norman Lear quote because it does really capture one the central themes that runs through all of your work, all of these different books that you’ve put out over the years. They have a common underpinning, which is trying to dig out and redeem what is best and most noble about American history, while as Lear says, spanking the country hard for its various transgressions.

This latest book that you have put out is a kind of recapitulation of this argument. Take Hold of Our History: That title captures something that also comes up in the Thomas Paine book and in the Four Freedoms book. You have that wonderful question: why do the ruling classes fear history? It seems like as a historian, and correct me if this is an unfair or imprecise characterization, you are exasperated by the way that reactionaries seize the story of American history and tell a nationalist myth. They tell a story about the country. In Take Hold of Our History, you have this fascinating chapter about Newt Gingrich, who you almost admire in a certain way. Newt Gingrich has a PhD in history, and you talk about the way that Gingrich weaves this story about the role of religion in American life, and how skillfully he does that. He creates a compelling narrative about America and sells it successfully.

And it seems that a common theme in your work is a frustration that we on the left—who have so many things that we can be proud of in American history—lose sight of all these great people who came before us and this wonderful story that we have to tell. And sometimes we lapse into a cynicism about American history. And we see it as a parade of exploitation and imperialism, which in many ways it is. But we also have this great democratic legacy and tradition that we can, as you say, “take hold of.” Is that fair?

Kaye

It is. Let me just say, I’m old enough to have a past even before Why Do Ruling Classes Fear History?, which was, I think, published in 1994. Just for the record, my childhood hero was Thomas Paine. So we’ll set that out as a marker. But it’s also the case that almost all of my studies—bachelor’s, master’s, and PhD—were in Latin American Studies. And I worked on landlord/peasant relations and things like that. And because of a whole long story that would take us a whole night to discuss, I ended up shifting radically to work on the British Marxist historians. And I published a first book, The British Marxist Historians—which, by the way, is coming out again this spring in a third edition—and it was in the British Marxist historians’ work that I really discovered a sense of how to write history that really did enable me to think about history in a more dialectical and class struggle kind of way. And in that sense, not to assume that the role of the left is simply to debunk, but actually, to ask ourselves: Why do our fellow Americans evidently feel so unsettled and so anxious and increasingly so angry about the state of America? I mean, we can answer that question. If we don’t consider the degree to which—this is going to sound a little culturalist, I admit—we carry a kind of deep cultural memory of the struggles that went into making not only an American republic, but all the more the struggles that in every generation have arisen to challenge the powers that be and make demands for the people, based on the original promise that was inscribed in American history by Thomas Paine and then officially pronounced in the Declaration of Independence and the preamble to the Constitution.

I wrote a book about Thatcher and Reagan, The Powers of the Past, in which I actually detail the way in which not only Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan grabbed hold of and made use of and abused British and American history to create a narrative that would obscure the struggles that I thought were important. And then in the 90s, I was pushed by a few of the British Marxist historians themselves saying, why don’t you write American history? Well, I ended up writing about Paine. And what I discovered was that I was wrong, that historians and biographers were wrong about Paine’s place in American history, that he had been so fundamental to the American Revolution, but that his memory had been suppressed for generations. And yet what I discovered—in some ways serendipitously spending all day in a library—is that in every single generation, every struggle that emerged—whether it was the free thinkers, the working mens’ parties, the abolitionists, the suffragists, the populists, the progressives, the socialists, labor unionists, and others—when they asserted themselves in a radical fashion, they often reached back to the American Revolution, and laid claim to Paine himself and Paine’s arguments to validate their claims, not only on the past, but their claims on the future.

And I thought, “Where are we, on the left, that we’ve become so good at debunking and critiquing?” And my generation wrote a lot of history from the bottom up. But why is it that, on the left, whether we’re talking about liberals, progressives, or socialists—why is it that those works have not found their way into the discourse of American politics through those who claim to be progressives? As a friend of mine said, “Why is it that the left refuses to lay claim to the heroes who are rightly theirs?” Why do they feel it necessary to take down the folks who—look, nobody is a saint, okay? We can lay out the names of people who are treated as heroes who weren’t, who were by no means saints. But the left has this instinctive look at history where they want to smack and debunk and deconstruct.

And I’m not saying everyone. But I asked myself the question: “How can this be?” And here’s what I think it is. In the wake of the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s, the left was in such retreat, that the instinctive response on a lot of people’s parts was to point fingers at the kinds of things that had been so long suppressed from the schoolbooks such as slavery, the marginalization of women, the suppression of labor movements—all things that we know about, and, by the way, are in the history books today. But it’s the case that the movements on the left will say—call it political correctness in a way—God forbid, somebody should talk favorably about Lincoln. Someone’s gonna say, “But didn’t you know that Lincoln did such and such?” Or about FDR. “Didn’t you know that such and such?” Well, I actually do think that liberal Democratic politicians—especially the neoliberal but liberal, Democratic politicians—ran and continue to run from history. I don’t think it’s just ignorance. I think they just literally run from history, because they’re afraid that Black Lives Matter, or the socialist left, or you know, the women’s movement will take them down. And as a consequence, they turn their backs on a history that also fails to consider the struggles from the bottom up—the struggles of slaves, the struggles of women, the struggles of workers. I can go right through American history.

So I mean, my point was that we have to speak—and I’m saying this in a political way—to the anxieties of our fellow citizens, and let history, in essence, remind them of who they are. We have to master the narrative far more effectively than we’ve done probably since, well, indeed, since FDR.

By the way, I’ll give you a footnote to that. Back in 1986, we were living over in England, and it was election year, ‘87. That summer Labour got walloped by the Tories. Absolutely walloped. Thatcher just triumphed. And I thought to myself, well, when did we hear Labour remind the Brits themselves of their own grand story of struggles, whether going back to the peasant rising or the labor movement? I wrote a piece for the Guardian. I wrote it so effectively that the editor titled it, “Our Island Story Retold,” and it clearly wasn’t my island, but it was the case. And I think that that made me all the more determined to ask similar kinds of questions here in the States.

I’m sorry, I went on so long.

Robinson

That’s a good place to start. Speaking of British Labour in that period, I was recently reading G.A. (Jerry) Cohen’s piece that he wrote in the 1990s about why Labour needed to get back to first principles. And he was looking at some of the arguments that they’d been making, the rhetoric they’d been using. And he pointed out something that recently showed how the Tories were actually raising taxes rather than cutting taxes. And he said, Well, you know, what are you doing with this kind of rhetoric? Well, you’re pointing out the hypocrisy of the other side, but you’re almost reinforcing the idea that raising taxes is a bad thing by establishing yourself in opposition to the hypocrisy of the other side. But what the other side are doing is weaving a narrative, a story, something inspiring. And he said: We need to get back to our socialist principles. We have something that we can be proud of. We have good ideas, we have an inheritance, we have a tradition. There’s so much that we shouldn’t give up in favor of pure critique, because pure critique inspires nobody.

Kaye

I was thinking about this whole idea of critique. This goes back probably to the ‘80s, the Reagan years, and I remembered somebody saying that the left always falls back on critique when it’s out of power. But it never really seeks to remind Americans of a story that would enable them to realize that the way things are is not the way they have to be, that you can critique and just satisfy people’s anxieties by letting them, you know, bellyache about things.

Before we started talking today, I was thinking about this project of mine that I’ve been pursuing all these years. And I was remembering that in the 1920s, the term debunk became part of the political discourse. And there was a popular historical writer who went after the idea that George Washington was the father of our country. And he made the case that it was really Thomas Paine. Now all well and good. But the point is, it’s in the ‘20s when the left really was marginalized. And labor unions had really been pushed aside after World War I. And you had the Red Scare, and then you had the immigration quotas. The left barely existed in the ‘20s. There was the new Communist Party, but the numbers were hardly worth talking about. The socialists were significant, but would never be as significant as they had been when Eugene Debs was alive. And I was thinking it wasn’t interesting. So in the ‘20s debunking became the thing for the left. And then, in the late ‘70s through the ‘80s, we fell back on that again. The tragedy is that we’ve been falling back on it for the last 45 years. On behalf of my fellow left historians from whose generation we call the ‘60s and ‘70s, there’s a hell of a lot of good history that ought to be articulated into a form that politicians on the left—AOC and Bernie—ought to grab hold of.

As much as I love Bernie and I voted for him—in the ‘80s I wondered if I’d ever get to vote for a guy like Bernie Sanders, and then he was on the ballot for the Democratic nomination in 2015-2016—I have a critique of Bernie in those terms. Okay. In 2015, Bernie Sanders was clearly the rising star—he’s not a Democrat with a capital d—but of the Democratic Party. And the Clintonites clearly were worried. However effective the machine might be that they’d created, they were worried. I think it was November of 2015. Bernie went to Georgetown University to give a speech to explain democratic socialism. Now, look, there’s a role for you writing about democratic socialism and Bhaskar [Sunkara] and all the rest of us. But if a politician has to go before the American people to explain what democratic socialism is, we’re in trouble. What I mean by that is, if you’re gonna have to spend part of your time explaining yourself, you’re not going to win the final election.

But more important than that, he did an incredibly amazing and brilliant thing. He linked himself to the tradition of FDR, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the better angels of LBJ’s nature. Now that was marvelous. Then what he did is he grabbed hold of the FDR that most Americans actually, deep down, admire, even if they couldn’t tell you the story of FDR. Okay. So I thought, this will be the turning point. This is where the Clintons will be on the run. And then what did Bernie do? He went back on the campaign trail and never mentioned FDR in any major fashion again. And Hillary, of course, picked on him because instead of Bernie talking about the New Deal and reviving it, he talked about Scandinavia. And she said, “Well, we’re not Denmark.” And she won that debate. And nobody remembers anything about it.

Robinson

Because Americans are suspicious of Europe and know nothing about it.

Kaye

Right. Look, I’ve been living in the Midwest for 40 years. I can tell you, you’re not going to convince any midwesterner, however much they may have Scandinavian roots, to vote for someone who’s gonna pitch a foreign country. Now, let me come to 2019. So now Sanders runs again. Great. And if one looked at his website, one would have said this is the FDR of the 21st century. I mean, it had everything, the labor question, it had the economic Bill of Rights and all that. But out on the campaign trail, he didn’t talk FDR. And I think it was probably November of 2019 when he decided he’s going to explain democratic socialism again. He did the same thing. He made a really great speech. And then he went back out on the campaign trail, and he didn’t pick up on it. And I can tell you that when the debates began, he should have done what Eugene Debs did in 1918, defending himself to the jury. Debs was convicted of sedition under the Wilson administration during World War I. And what he did in his own defense is he stood before the jury, and he actually started to call into the courtroom Thomas Paine, Patrick Henry, and Abraham Lincoln. He actually called into the room radical and progressive figures from American history in defense of his own politics and his socialist understanding of the world. Well, Bernie, on that debate stage, every time he spoke of, say, Medicare for All or anything else, the likes of Buttigieg, or Harris, or somebody came at him for being ready to bankrupt the United States. What Bernie should have done is called FDR into the room and reminded the Democrats that if they think they’re the Democrats with a capital d, that he’s the socialist with a capital s, they’re missing out on the fact that he stands alongside the greatest Democratic politician ever.

Robinson

So the argument here would be that instead of saying, “Well, you have all these social democracies in Europe, and they seem to do quite well,” you don’t need look at these other places that Americans don’t know about. In fact, you can appeal to things that Americans have just forgotten in their own past. You can say, “Well, what has actually happened is that the Democratic Party has lost everything that made it worth voting for.” There’s something that we can be proud of, that has been abandoned and betrayed.

I mean, obviously, I really don’t like the word patriotism, because I just think the connotations are so ugly that I never agree with those who say, “Oh, we want the left to reclaim patriotism.” But I do think pride in various parts of the American story and American culture is something that I have. I mean, there’s so much that has just been deliberately suppressed. Of course, you can speak about the radical King. We have this advantage with Martin Luther King, Jr. where he’s been elevated to sainthood, essentially, where no one can speak ill of him. But what they do is they just make sure that nobody actually listens to anything he said, right? But what that means is that we have one of the American saints that you can’t speak ill of who endorses, basically, the entire Bernie program.

Kaye

Two things I’ll remind you of. Do you remember Michael Moore’s film, Where to Invade Next?

Robinson

Yes.

Kaye

Well, most people seem to have missed the point of that movie. He was not praising the Europeans for their innovations in social policy. His whole point of the movie was to say, every one of these things, as a progressive initiative, was rooted actually in the American story. He says it.

Robinson

I remember. If people aren’t familiar with it, Michael Moore basically goes and looks at other countries—he looks at the school lunches in France, and health care in different countries. And he looks at all of these things they have. The title is like, we should invade these countries and take their innovations, but then the twist that he puts on it is, then he comes back to America. He’s like, Well, wait a second, all of these things have deep American roots. And we don’t have to necessarily look around the world. The answer was within ourselves all along.

Kaye

We’re not going to get anywhere telling people how good it is in Sweden. For example, how many people do you think in America would know who the father of Social Security is? And maybe you don’t, either?

Robinson

Who is the father? Thomas Paine?

Kaye

Thomas Paine! “Agrarian Justice.” He begins with the rights of mankind.

Robinson

I want to talk about Thomas Paine. You’re one of the foremost Thomas Paine experts in the country. You’ve written about him extensively. He’s in this new book. And one of the arguments that you make in the piece on Thomas Paine and in the new book is that we need to read Paine and reclaim Paine. And it is absolutely true that, of the Founding Fathers, Thomas Paine is the least discussed, despite being probably the single most influential—or at least a man without whom I think it’s pretty clear the American Revolution would not have happened.

People who discover Paine always all go through this wonderful revelation, where you realize that this person without whom the country would not exist, was so bitingly critical of religions, such a strong defender of democracy, was against slavery. He lacked all of the vices that make so many of the other Founding Fathers such an embarrassment and so difficult to take true pride in—because whatever their accomplishments, it’s very difficult to celebrate anyone who owned human beings. But Thomas Paine is a very different story. And because Thomas Paine is someone you could be proud of, who stood up on principle, there was a deliberate effort to suppress and forget Thomas Paine’s contribution.

Kaye

And if Paine were alive, he would say, “But please understand, what I really did was to show Americans what they were already doing.” In 1774 and 1775, Americans literally rose up and ejected British authority from government roles. And they created committees. It was an anarchist’s dream. The colonials literally established committees to govern themselves through the course of 1775. In fact, the irony is, the first person to realize what was at stake in all of it wasn’t an American. Paine hadn’t even arrived in America, other than some weeks before this speech was given. Edmund Burke, the father of modern conservatism, went before Parliament to warn his fellow parliamentarians and said not to push the Americans any further, that they might realize they’ve already carried out a revolution. Nine months after he gave that speech in Parliament, Paine publishes, with the encouragement of Ben Franklin and others, the call for the revolution.

But even then, the first call in the pamphlet “Common Sense” is to remind Americans that they were instinctively democratic, that humanity is instinctively sociable and democratic, and that it’s the British who have imposed this terrible regime on us. And it’s imperative to get rid of kings and literally create a democratic republic. Paine’s brilliance was that he saw his fellow citizens and held up a mirror to that. To go back to Bernie, Bernie recognized how angry Americans were, and that’s why he harped on the billionaires. What Bernie didn’t do was remind Americans why they might feel that way. Indeed, socialism is back on the agenda in various forms. But in my mind Bernie could have created a narrative that other politicians would have either had to embrace or, literally, switch parties.

Robinson

And by that you mean the idea that we don’t like kings. We’re a country founded in opposition to the rule of kings, and billionaires essentially have become monarchs, right? They are unaccountable, right?

Kaye

Right. Well, even FDR called the likes of the billionaires—the multimillionaires of the ‘30s—he called them economic royalists.

Robinson

Yeah. And drawing that connection in people’s heads between King George and Jeff Bezos can really be quite powerful.

Kaye

Or Donald Trump. A petty king.

Robinson

In a golden tower ruling over you.

Kaye

Yeah. Exactly.

Robinson

There are a number of inspiring things about Paine. As a writer, I’ve taken a lot of inspiration from him because he is someone who is a debunker, right? He essentially debunks the Bible. He goes through and points out all the eternal contradictions meticulously. In “The Rights of Man,” he’s debunking Edmund Burke while writing this takedown of Edmund Burke. But the other thing is that he is a democratic (small d) writer in that he has faith in the public, in a wide public to be able to appreciate sophisticated ideas, and one of the incredibly inspiring things about Thomas Paine’s writings about Common Sense is you realize that this is a guy who did not dumb anything down for people. He had a great faith in people’s ability to understand his argument and he managed to succeed in getting really strong, radical political writing to an absolutely massive audience with actual historical effect.

Kaye

Everyone should realize that he was raised in an artisan household, in the upper reaches of the working class. His father was a corset maker. Paine apprenticed as a corset maker. But it’s also the case that he did attend school up until the age of 13. He loved British literature, Shakespeare, Milton, and Bunyan, apparently, and he actually aspired to be a poet, which did not happen and his poetry is fairly mediocre. But his writing has a poetic character to it. Paine really understood that working-class people were underestimated because he was one of them. And so he knew how to speak in a way that didn’t speak down to people. So the debunking that he does starts by opening with a question of democracy. And he reveals to his readers, who he knows are going to be predominantly Americans, the degree to which what they are already doing is carrying out a revolution for—he never uses the word—democracy. Okay, he actually envisioned a community meeting under a big oak tree to deliberate and create rules that would govern everyday life. And then he goes on to debunk the revered English Constitution, the role that kings have played. He uses reason; he uses history. He uses incredible, even vulgar, humor to pull them down. And then he comes back. He comes back to the people. And, by the way, he drops hints. We should be wary of rich people, too, not just kings. At one point, he says that the rich are afraid. He doesn’t mean they’re afraid to make money. What he means is they’re afraid to say what needs to be said. We need a revolution.

Robinson

One of the pieces of advice you have in the book is that we should read Paine, not just respect Paine. Some of Thomas Paine’s writing is incredible. You really don’t get it until you read it. I am a strong advocate of going back to primary sources because oftentimes historical characters are so much more interesting than the third person description of them. As I was reading Thomas Paine’s writing, I found things about corporations. There’s anti-corporate stuff in there. You mentioned the humor. I’m a big fan of the “snarky parenthetical aside,” and at one point he quotes a Bible passage: “And the Lord ordered all of them slain.” He just puts in a parenthetical: “(the Bible is full of murder).” It’s just so funny, so snarky, so irreverent, and it’s so fresh. And to hear that voice coming to us from hundreds of years in the past is just an amazing feeling.

Kaye

You know, his mother, who was an Anglican, made him memorize the Bible. His father was a Quaker. The Quakers believed in a sort of an inner light. There was this contradiction in the family in terms of religion. And he could probably sense the contradiction. And the more he reads the Bible at his mother’s command, he basically realizes that this can’t be God. He believes in God. He’s young. He thinks God would not be this cruel. He rejects that. Okay. That’s that parenthetical statement about the murderousness. That’s the same Paine who was commanded to read the Bible.

Robinson

He detests the Bible. I mean, what’s so interesting is that he’s scathing about the Bible, and organized religion, but he’s such a strong defender of God. In fact, he says, “There is a Bible, and the Bible is the natural world. We need to be inspired by the world around us, which is what has been actually created or revealed to us by God.” Basically, he doesn’t like the Bible because he finds that it cheapens our wonder at the natural world, at all of creation around us.

Kaye

He says, “My religion is to do good.” And he says, “The model for that is the creation itself, that God, an all-powerful being, created the earth and humanity, and that this was an incredibly generous gift. And we should all take that as an example of what we should be to each other.” I first read The Age of Reason when I was 15. And I remember there was this question: Well, where is God if God created all of this, and what is he or she doing now? Somewhere in The Age of Reason, there is an answer, which is probably what the physicists came to believe. It’s the idea that the universe is expanding, and maybe the creation is continuing. And I do believe that Paine makes a reference to that. It’s just an aside that I remember from when I was 15.

Robinson

When you tell me that his mother made him memorize it, that makes sense. At one point, he says something like, I’ve not been able to access an actual Bible because I’ve been writing this while I’ve been imprisoned. And yet, he’s quoting chapter and verse from the Bible. He says, I’m sorry that I haven’t been able to check this in an actual Bible, but I know it’s there. It puzzled me when I read it, but now I understand. He just knew it by heart.

Kaye

One of the things that for generations British school boys had to memorize was poetry. And when I was living in England on sabbatical, when I was just living there for a while, I could not get over that men my age, more so than women, really did know poetry. They could recite it without having to look at it. Over dinner they could bring it up. I used to think to myself, Oh, God, if I could do that, I’d really be effective. Paine basically learned how to remember these words in books. Don’t people marvel when they discover that figures like Marx and others learn more than one language? I mean, damn the television, right? That’s all I can say.

Robinson

It’s just a fascinating life and someone from the founding generation worth reclaiming, someone who can be considered pretty heroic. And then Paine’s internationalism. Not only does he help set off the American Revolution, but then goes in support of the French Revolution. And then he’s turned upon, basically by everyone. He’s a person of principle. It’s also a story of what happens if you refuse to flatter the powerful. He ends up alienating himself from the rest of the founding generation of Americans, from the French revolutionaries, from British elites, right? In the end he’s a man without a country and then infamously dies in poverty.

Kaye

To his credit, one of the founders who never turned on Paine was Jefferson. Somebody wrote a letter to Jefferson—I don’t remember whether it was an American or British or French person—to ask, Who do you believe the greatest writer of The Revolution was? And Jefferson was a renowned writer, but he knew that he himself wasn’t the greatest writer of The Revolution. And Jefferson said Paine was that man. He said Paine’s words made The Revolution happen. It’s the very same Paine who utterly pissed off the likes of John Adams, and those who were destined to become Federalists, and the worst of the elitist bunch.

Robinson

Which is what you have to do if you’re going to be a person of principle.

Kaye

If anyone wants some entertainment at night, get a copy of the letters between Jefferson and Adams. Jefferson is always careful about what he says. He’s always careful. They call him the Sphinx because you never quite know. And Adams writes as if he’s on a therapist’s couch. He lets everything out. The words he uses to describe Thomas Paine and his writings are utterly gross. Then there’s Jefferson sort of not responding, which pisses Adams off all the more.

Robinson

Judicious silence. You cite that quote from Teddy Roosevelt calling Paine the filthy little atheist?

Kaye

Yeah. Paine was neither filthy nor little nor an atheist. There were times he may well have been so deeply immersed in his work that he probably needed a bath and probably had had a few drinks too many. He was not little in terms of the times in which he lived. He was five foot nine or five foot 10, which was actually rather athletic in those days. And he was no atheist. He was a deist. But it’s Teddy Roosevelt, not Franklin Roosevelt.

Robinson

It is quite easy to mistake him for an atheist at various points. If you take the quotes that he has about the Bible and religion, and miss the other half of it where he’s talking about the wonders of God’s creation—he’s just as scathing about organized religion as Richard Dawkins.

Kaye

Absolutely. There’s no question about that. He said that one of the reasons he wrote The Age of Reason was the fact that the Jacobins, those who had come to prevail in the course of the French Revolution, were not only shutting down Catholic churches, but persecuting religious believers, and then constructing their own church of reason or temple. In other words, his feeling was that it was imperative for him to defend God. Paine believed he was defending God.

Robinson

Nobody religious believed that Paine was defending God.

Kaye

Nobody. Absolutely not.

Robinson

He did not successfully persuade anyone that that was what he was doing.

Kaye

No, absolutely not. It is the case that throughout American history, those who never failed to grab hold of Thomas Paine were, in fact, the atheists through the years. It’s a fascinating story. Paine’s legacy really did inspire radical ideas and radical politics and labor unionism and socialism and all the rest. And it’s a shame that we spend more of our time on the left going after the Founders rather than promoting Paine the Founder, you might say. By the way, Ronald Reagan, who was far more brilliant than anyone on the left ever appreciated, when he was running for president and finally won the presidential nomination—

Robinson

That’s a controversial statement you just threw out there.

Kaye

Ronald Reagan was brilliant. I’m not saying he was an intellectual. I’m saying he was a brilliant politician.

Robinson

Right.

Kaye

In 1980, running for president once again, on the campaign trail, Reagan grabbed hold of the most radical line in modern history, which was from Common Sense. “We have it in our power to begin the world over again.” And it was his acceptance speech at the Republican Convention. Now keep this in mind. In that very same speech, he quotes Thomas Paine’s most radical line, and one I would argue is the most radical in modern history. He quotes Abraham Lincoln, and then he quotes Franklin Roosevelt. The conservative Republicans didn’t know what to make of Reagan when he did that. George Will—can I use the s word?

Robinson

Yeah.

Kaye

I’m sure George Will shit his pants. Because he wrote about it. He said, What kind of conservative quotes Paine and not Burke? Reagan knew that Americans had a deep affection for Paine, even if they couldn’t recount Paine’s life and words. And a deep affection for Lincoln, and for FDR. And he used it in a magnificent way in his acceptance speech.

Robinson

Conservatives are engaged in a project to select little pieces of history in order to create national myths and stories that are erroneous. But if no one’s going to tell the true story, then they can get away with it. So you point out in your book that Glenn Beck wrote a book called Glenn Beck’s Common Sense and said that Thomas Paine was the Glenn Beck of his time.

Kaye

That book he wrote was disgusting. Glenn Beck literally turned every single one of Paine’s arguments inside out and upside down. There was no link between Glenn Beck and Thomas Paine.

Robinson

That’s why it’s important to return to the original writings. You can’t lie when you actually open up The Age of Reason. It’s incredible, scandalous. Some of the stuff he says still feels provocative, even here in 2021, even now that organized religion has been on the decline for a while. He’s so aggressive. It’s amazing how fresh it seems. We’ve dwelled upon Paine, but he’s a case study. Paine, as you say, is the greatest of the founding generation, and someone who obviously we need to reclaim. But in every single generation, there are figures who were doing the work and who were invoking the values that we hold, and they have all disappeared from view. If no one tells their stories or quotes from them, and if no one tells the truth, they become neutralized. Martin Luther King, Jr. is the obvious example. He becomes a series of uplifting platitudes about how we all want to get along with one another, and then you lose all of the force of his anti-imperialism and his radical calls for economic democracy and his tributes to the labor movement. Take Frederick Douglass. A few months ago, I read a speech of his where he’s talking about labor in the post-slavery south. And he’s talking about the sharecropping system. He’s talking about exploitation. And he’s talking about how emancipation had become a joke. It’s a sick, twisted joke because of the reality of what it means to have no capital and to have everything you earn be taken away by your landlord. All of this stuff that Frederick Douglass said, I never knew because nobody ever teaches it.

Kaye

Well, yes. And in the 20th century, how many Americans recognize the name A. Philip Randolph? He was not simply a major labor leader and a major civil rights figure, but was also a socialist. He gave a speech in the middle of the 1920s in the sesquicentennial of the American Revolution. He said that the historians really failed on the question of Reconstruction. How often do they point out that Reconstruction is the time in which African Americans brought democracy to the south for the first time ever? And then he says—and I love this line, I wish he were alive during the Black Lives Matter movement—”In this century, we will bring economic democracy to all of America.” You know, it was the sense of these radical figures who knew how to speak in a way that both didn’t just offer a vision and a promise, but spoke deeply to what it meant to be an American. You know, I’ll give you a sidebar example of what I’ve been talking about. So when AOC was elected to Congress, because she was a democratic socialist and a young woman, Anderson Cooper or somebody of his ilk interviewed her. But he basically asked her if she had any hope for American progressive politics, and she cited Franklin Roosevelt. Sorry, Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Roosevelt. She cited them as proof of what might be possible. Two presidents who in their respective ways radically transformed America in the midst of tremendous crisis, empowered, in the first instance, by white workers who fought in the war and African American slaves who made it a point of going to the Union lines such that hundreds of thousands of them would serve in the Union forces. And with FDR, the labor movement of the 1930s. And would you believe, the New York Times interviews a few historians, a couple of them leftists. And they all offer a little critique of her references to Lincoln, and to FDR. Well, why the hell would you offer a critique from the left of references like that? Because of the need to debunk it. They should have said that it’s great to hear an American political figure of the left lay claim to the American progressive story. I mean, that’s the thing. We’ve just got to do this.

Robinson

Well, I want to ask you about how you think about FDR. Leftists typically talk rather cynically about everything FDR did: that he was trying to preserve capitalism and the labor movement had to force him to do various things. And he wanted to preserve the ruling class and therefore had to make concessions. And also, the hideous human rights abuses of the internment of the Japanese is a really serious blot on his legacy. So what do you think is the correct story to tell about Roosevelt and the New Deal?

Kaye

Let me make clear: there are three major political tragedies of FDR. The first one is the internment of Japanese Americans. I think it was called one of the worst civil rights abuses in American history. Okay. But it’s worse. I mean, it’s tragic. The second one is the fact that he did not purge the State Department in order to possibly enable more Jewish refugees to escape Hitler’s Germany. But it’s also the case that Congress was filled with antisemitism, and they were determined not to allow it. And even Robert F. Wagner, the German American Senator from New York, could not get them to lift the immigration quotas. And the third one is the fact that he allowed the military to talk him into setting a 10% limit on African Americans serving in the military and created a Jim Crow military. There’s no denying that.

So, first of all, this idea that the labor movement made him do it. Well, in the first 100 days, the labor movement itself was still reeling from 1920 and the Great Depression of 1930, and FDR signed into law the National Industrial Recovery Act—which is not the National Labor Relations Act, that’s ‘35—in ‘33 he signed into law the NIRA, and that included collective bargaining rights for workers and the very first minimum wage in America. So the fact is that FDR empowers labor, in good part by his own account, to push him all the more.

There’s an increase in the dialectic between Roosevelt and working people that is fascinating. FDR encourages and engages Americans in their labors for the New Deal, but also to empower them to organize. In 1935, FDR gave a speech and he said, new laws in themselves do not bring the millennium, and what he meant by that is you’re still gonna have to fight. So I think the knee-jerk response of the left is actually just dumb. FDR was undeniably a progressive and a social democrat who made some terrible, terrible decisions along the way.

But if you put together the first 100 days, the second New Deal, Social Security, the National Labor Relations Act, the Fair Labor Standards Act, and then during the war, a whole host of—it’s almost like a third New Deal, you might say. And then in 1944, he called for an economic Bill of Rights, knowing that Americans want social democracy (he’s run a bunch of surveys), and he puts it on the agenda. So I think the left has really done damage to ourselves by not laying claim to Lincoln and FDR. I really do.

Robinson

And it’s other figures, too. When I was writing my book about socialism, I wanted to talk about Helen Keller and Albert Einstein. And you can talk about Eleanor Roosevelt. You can go through history. When you read people’s actual writings, you find so much to inspire you, so many brilliant people who struggled against the oppressive conditions of their time.

Kaye

Listen to this. Here’s an argument, and you can debunk it, if you wish, okay? Even though I’m your guest, take it on if you wish.

Robinson

Okay.

Kaye

I thought about this after I did the Paine stuff, and then they did the FDR Greatest Generation stuff. I am absolutely convinced that Americans are essentially radicals at heart. And the first proof is the degree to which in every single generation, there has been a significant radical—or if you prefer, progressive movement—that has emerged to challenge the status quo. And I mean, this is over and over again, and in its diversity alone, it’s extremely impressive. That’s the first point. But more important than that, in a punchline kind of way, is this. The three greatest crises in American history were in the 1770s, the 1860s, and the 1930s and ‘40s, a dual set of crises. I would say to students: Why, when asked, do Americans believe the three greatest presidents or leaders were Washington, Lincoln, and FDR? And inevitably, the answers they gave were something like, well, they led us through wars that we won. But FDR’s greatness is predicated as much on the ‘30s as anything to do with the ‘40s, World War II. What we don’t realize is that they not only led us in the midst of crises, in order to transcend the crises, and Americans actually radically transformed America in each instance. So The Revolution was only won because Americans followed the spirit of Paine’s Common Sense and created a democratic republic. Look, a lot of folks would not have lined up in The Revolution if it wasn’t for the promise of democracy and separation of church and state. That’s fundamental. And both of those are at the heart of Paine’s Common Sense. I’m not exactly sure the North would have won the Civil War had it not been for the Emancipation Proclamation and the fact that a quarter of a million African Americans ended up serving in the Union ranks. And I can tell you that the New Deal would never have prevailed had it not been for the empowerment of labor—by the way, that labor and working people demanded. So, FDR was not as aggressive on the labor question as the bills he signed into law. But in those moments, it’s the case that the only way America transcends a crisis is that Americans, despite everything, radically transform what they’re about. Of course, later, things are sometimes shoved back into place. Reconstruction gave rise to bourbon regime, the Cold War, McCarthyism, and everything else. But when push comes to shove, Americans have asserted a radicalism—by the way, I’m going to really shock the shit out of you now. Conservatives love to talk about American exceptionalism. And the left says, F you, there is no such thing. The exceptional part of the American story is the radical story, the unparalleled radicalism of the American story, however sad it may look today. Things are happening. Things have been happening. And, you know, we ought to draw inspiration and encouragement from that.

Robinson

Well, this is what I like about your work. Many leftists, as you mentioned earlier, will react with our typical cynicism. You know, LBJ, Vietnam, horrible. But to the extent that LBJ is fondly remembered, it’s because of the Great Society. It’s because of civil rights and voting rights. And these are things that we need to know. We can take the good, and we can condemn the bad. We don’t have to think in binary about the villains, put everyone in the villain box. We need to mine the rich storehouse of history for those things that we can cobble together into a story of the country that inspires us and into a program for the future. What I like about your books is that there is something that runs through all of them. The final chapter of this book says, we are radicals at heart, don’t you forget it. This captures what you’ve just been saying. In the post Bernie moment, the American Left is somewhat adrift. People don’t know what we’re going to do next. People feel very hopeless, especially because of climate change. And what you give us in these various works is a way to look forward by looking backward, to look at the utopians, to look at the labor organizers, to look at the civil rights movements, socialists, and to take all of it and notice that they worked under conditions often much harder than we face. I mean, they faced kinds of oppression that, we have managed to, for the most part, eradicate, and that gives us a place to start. And it gives us a leftist philosophy that I think can really fill our souls, and you’ve got to fill people’s souls. I think when you said Reagan was clever, I think you were right. And one reason Reagan was clever is Reagan knew how to fill people’s souls. And until we learn how to do that, I don’t know that we’re going to capture the public imagination.

Kaye

I mentioned poetry earlier, and that I couldn’t memorize it very effectively. But there are a series of poets in American history who really do capture the American story. With my students, before we started the course in historical perspectives on American democracy, I had them read the poem by Langston Hughes, “Let America be America Again.” Let America be America, again, the land that never was, but must be. And he really does capture the struggle that has always been at the heart of the American story for all of the exploitation and all of the oppression.

People should go back and read Douglass’, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” I used to assign it to my students and say, Tell me—and you’ll excuse the word I’m about to use—is Douglass an antagonist or a patriot of America? And I always knew who read it all the way through because it’s a lengthy sermon/speech that he gave in 1852. And those who came back and said he was an antagonist only read halfway through, because you can’t read the last half a dozen paragraphs without realizing that Douglass, despite all of the berating of the American story, says, and yet, there’s an American promise that is so powerful, that we can prevail. You might read it at bedtime. If you’re feeling despondent, keep in mind that it was the age of slavery in which half of the United States was dominated by white supremacists who could decide on life and death for an individual.

Robinson

If Martin Luther King, Jr., days before his assassination, could say that he could see the promised land, that he could keep moving forward, then who are we to lapse into cynicism, despair, and inaction?

Well, professor Harvey Kaye, thank you so much. I wanted to talk to you for a long time because your books are rich with inspiration for people and inform readers about many things about the past and things about their country that they didn’t know. The most recent book is Take Hold of Our History: Make America Radical Again. Professor Harvey Kaye, thank you so much for joining me.

Kaye

Nathan, thank you very much. I really have been looking forward to this opportunity. Thank you.