Why Is The Pursuit of Money Such an American Obsession?

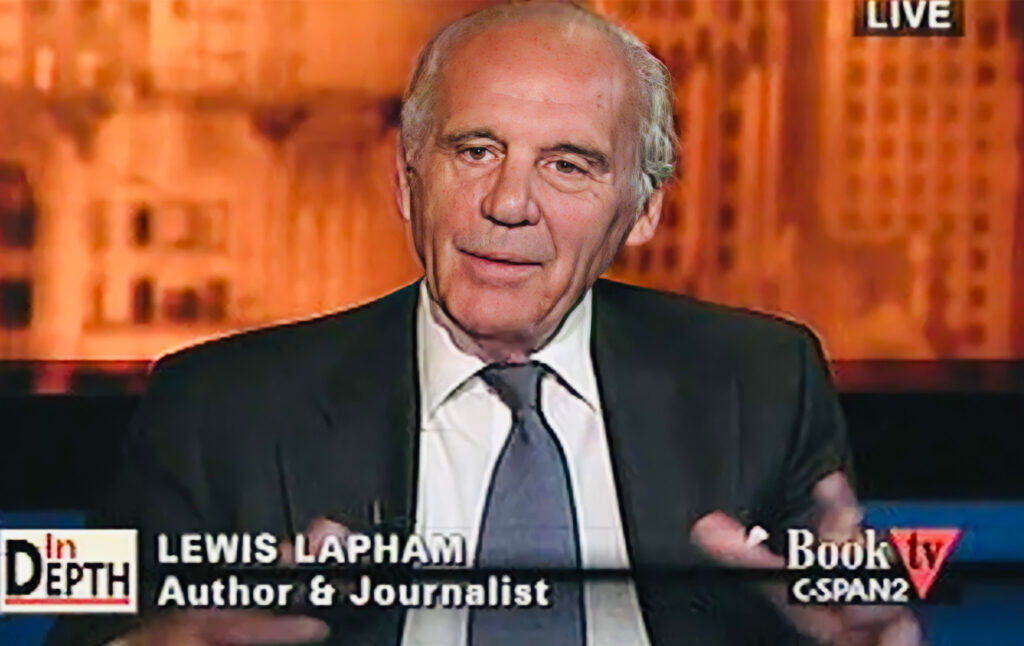

Legendary former Harper’s editor Lewis Lapham talks to Current Affairs about his decades chronicling the dysfunctional social mores of the American ruling class.

Writer and editor Lewis Lapham has spent years chronicling the world of the American elite, in books like Money and Class in America (recently reissued by OR Books), Lapham’s Rules of Influence, and Age of Folly, as well as in his fascinating and quirky documentary The American Ruling Class. Lapham served as the editor of Harper’s magazine for nearly thirty years, before founding the unique Lapham’s Quarterly. He recently joined Current Affairs editor in chief Nathan J. Robinson on an episode of the Current Affairs podcast to discuss the world of the American ruling class. The following transcript has been lightly edited for grammar and clarity.

Robinson

If people don’t know your background, much of your writing focuses on the inner lives of the American elite. You were born into that American elite. Your great-grandfather was a co-founder of Texaco; your grandfather was the mayor of San Francisco; you have moved through the upper crust of American society throughout your life. You went to Yale and Cambridge. And that’s what you’ve written about. Sociologists often lament that ethnography has focused too much on the lives of the poor without looking enough at the lives of the rich, who are a fascinating subject in and of themselves. I want to start with your early life, being born into this world of the American upper crust. Do you remember when you first began to see the social milieu that you were in as strange or unsettling, when you began to take on this kind of perspective of being someone who saw it from the outside, from a distance, seeing things as quite odd that other people saw as normal?

Lapham

Well, let me say that, as the son, grandson, and great-grandson in a family that owned oil and shipping companies, I was welcomed at birth into the hospitality tent of gift-wrapped humbug that shelters bourgeois privilege from the rain and raineth every day. Like Caesar’s Gaul, a humbug divided into three parts:

- Money ennobles rich people, and corrupts poor people.

- Money in sufficient quantity entitles its possessor to the reverence and respect owed to the statue of George Washington.

- Money is the sacred elephant, always in the room, never to be addressed or seen, but whose will is done on earth as it is in Heaven.

I mean, the message didn’t come engraved on a silver tray. It was to be inferred by the weight of the silver tray. Whether in polite company or home alone with the children, my parents never discussed money. Vulgar mention of the sacred was blasphemy. Money was best left unmolested and unknown—what Plato would have recognized as the noble falsehood that provides a society with its self-preserving myth. The children of the city must be told that the God who made all of them makes gold into some of them, who are therefore entitled to rule because they are the most valuable. Whether the intel is true or false doesn’t matter. What matters is the children of the city doing their duty to believe it, to know what their rulers would have them know, in order to maintain the health and well being of the body politic.

At the age of four in 1939, I had no reason to ask whether the intel had been fact-checked. The house was well supplied with silver trays, the picture windows afforded handsome views of the bay, the servants knew their place. I began asking questions at prep school and college, in Ivy League Connecticut in the 1950s, and then as a newspaper reporter and magazine writer, resident in Manhattan in the 60s and 70s. And I caught a frequent-enough sight of the elephant—on the golf course, on the beach, the Council on Foreign Relations, at fundraising dinners, on Park and Fifth Avenue—to mark its divinity as overrated and overpriced, a naked emperor clothed in the magnificence of my own stupidity and fear.

Robinson

You write a lot about the kind of falseness or self-delusion that exists among this class of people. You write about some of your observations of students at Yale in the 50s and how the wealthiest students deliberately wore rattier clothes intentionally or affected this air of carelessness. I had a similar kind of observation when I went to Yale Law School. It was very bizarre, the lack of discussion of what everyone knew to be true, the hiding of people’s motives. When you did the interviews with the Wall Street law firms, you were never supposed to hint that you wanted the job because it paid well. You had to be very, very careful to come up with these elaborate explanations…

Lapham

Yeah. Right.

Robinson

…of why you would want that kind of job that wouldn’t involve the money. “Oh, I just find the law a fascinating puzzle.” The same is true with the application essays to the law school. You could never say “I would like to come to Yale Law School because I would like to get a well-paying job that would set me up for life.” You had to profess your devotion to the public interest even though it was quite obvious that one of the primary reasons you would want to go to law school and why you would ever want to take one of those jobs would be that the job pays really well.

Lapham

Yeah. Right. In 1984, I think half of the undergraduates at Yale applied to either Morgan Stanley or JPMorgan Chase or a bank on Wall Street. But also, in 1988, in the Yale dormitories on the undergraduate campus—in the prides of place that had been reserved in the 60s for photographs of Dylan and Che—in 1988, the pride of place was a photograph of Donald Trump. Donald Trump was the absolute hero of the age in 1988. A picture on the cover of Playboy, a picture on the cover of Time, his bestselling book, The Art of the Deal, was the first book that was published by one of the big New York publishing houses.

Robinson

You know what the first sentence is in The Art of the Deal? “I don’t do it for the money.”

Lapham

Yeah. It’s the same pretense, right? I mean, that goes back to the beginning. America was not founded as a democracy. It was founded on a dream of riches. The forefathers who arrived—the Puritans who arrived in Massachusetts Bay in the 17th century—came in search of riches: spiritual, temporal, animal, mineral, and vegetable. Within a matter of a few years, they start arguing the question as to whether money is mortal or immortal. Wages of sin or proof of grace? Proof of the good Lord’s infinite wisdom or product of a sweetheart deal with a massacred Pequot Indian? I mean, the whole idea of what money is and what it means to Americans is really the whole of our history. That argument.

Robinson

Oftentimes, you emphasize this treatment of net worth as a synonym for virtue and people measuring each other by what they possess.

Lapham

Yeah.

Robinson

Also, as we’ve said, this kind of denial that anyone would be engaged in selfishness or pure acquisitiveness, even though it’s quite obvious. I mean, hypocrisy is the other theme of the book, this profession of noble virtue.

Lapham

Yes. Right. That goes back to Plato: “When wealth and the wealthy are valued in the city, virtue and good men are less valued. What is valued is practiced. What is not valued, is not practiced.” And virtue is not practiced. But we want to pretend that it is. What’s valued is wealth. And what we pretend to value is virtue. The more heavily we value wealth, the more ostentatiously we pretend to virtue. You know, the torn khaki pants, the scuffed shoes, the way our millionaires like to dress today, or the way that kids were dressing at Yale in the 50s. You know, it’s a pretense to virtue.

Robinson

When you write about education, there’s another passage where you’re talking about how you realized that there was not, in fact, an expectation of you to get a deep understanding of the humanities and philosophy, but there was an expectation that you would be able to name-drop the right philosophers and give the right talking points—all the signs of having an education rather than the substance of an education.

Lapham

Yeah. That’s right. That’s what it was about. Archibald MacLeish makes a remark in the 30s. He talks about that. He says that the busts of the great Greek philosophers stand around in shelves of university libraries, but we’re supposed to admire them as abstractions, not as living force. “Liberty,” says MacLeish, “we’ve made a thing to save and dug it around a dead man’s grave.” I mean, it’s not the exact quote, but it’s like that. In other words, the classics become naming opportunities.

Robinson

One of the other things that really comes across in Money and Class in America is this kind of deep inner sadness and emptiness that exists in the lives of the extremely wealthy. This is partially because, of course, the ceaseless desire for acquisition means that one can never have a satisfied life. You have one story about a guy who asked his father why the father never told him he loved him. The father said, “Well, I’ve dealt with you the same way I’ve dealt with the Justice Department and the IRS.” Another story struck me, that of the woman that you watched trying to get connected to Senator Edward Kennedy at a party. You saw in her this kind of stone cold—this sad ambition in her eyes. You talk a lot about this peculiar coldness. You say that the rich have the temperament of lizards. Their “indifference to other people’s joy or sorrow bears comparison to the indifference of the stars in the constellation of Orion.” It’s a deeply, deeply sad world emotionally.

Lapham

Well, yes. There’s a wonderful line by—I think it’s Schopenhauer—who says that money is human happiness in abstracto. People who cannot experience human happiness in concreto—in the concrete, in the specific, in the flesh—put their whole hearts on money. I mean, people at a certain level of wealth come to imagine that their money is their self, and, therefore, immortal. I mean, when Trump comes down the escalator in 2015, he essentially stakes his claim to the candidacy for the presidency on the fact that he’s really rich. And he says, money is power, and power is not self-sacrificing. Democracy is for losers. Because I am really rich, I can sit, say, and do whatever I want to say and do. Melville makes the same point in 1930. He says, “Americans, among ourselves, we are the first people in the history of the world to make selfishness [seem like] philanthropy.”

Robinson

Ray Dalio, manager of the hedge fund Bridgewater, said the degree to which you make money is a measure of the degree to which you’ve given society what it wants. Part of the core of the free market philosophy is actually that the making of money is a direct measure of your human virtue.

Lapham

Carnegie says the same thing in “The Gospel of Wealth.” But he also says that the amassing of wealth is idolatry. He also says that a man dies in disgrace unless he’s given away all of his wealth.

Robinson

Yeah, that part of it, the second half of “The Gospel of Wealth,” disappeared from the equation over time.

Lapham

Yeah. Right.

Robinson

You can’t have been terribly surprised when Trump became as successful as he did. I know that you have been comparing America to a vast hotel, long before the Trump presidency. And so seeing a hotel tycoon become the president of the United States almost seems like the logical conclusion of the trends. And I can see why you reissued Money and Class in America because, I have to say, it does not read like it was published in the 1980s, even though its references are to the 1980s. It did seem like the culmination of a trend that you watched unfold.

Lapham

Yes, and it is still with us. We still haven’t figured a way around making a god of money. I mean, until we cure ourselves of that delusion, we’re going to find it very hard to figure out a way to confront the problems of the 21st century. People write books about this all the time. America in decline. What happened to democracy? What do we do now? How do we save the climate? And so forth and so on. And the people that believe in the divinity of money, believe that they can buy the future, and not only McMansions and Southampton, but also world empire. People around Bush and Bush himself thought that empire could be bought. People pushing the Sanders agenda, for the Build Back Better bill, are thinking that social justice can be bought. But the future can’t be bought. It has to be made. It’s not a commodity. I mean, the socialist is just as fixated on money as the capitalist.

Robinson

That’s a fascinating thing to say. The fight over the legislation is over whether we’re going to have $3 billion or $1 billion. It’s all just talking about the amount rather than getting beneath the surface to consider what we are actually going to do to affect people’s lives. It’s still measured in currency.

Lapham

You ask, what are the qualifications for the American ruling class? My answer to that would be the same answer that Tocqueville gives that I mentioned in Lapham’s Rules of Influence, which is, if you want to get an interview for an “A” birth, or for a birth on the “A” deck of the American ship of state—by which I mean the executive positions, not only in the corporations but also in academia and the media and the think tanks—you have to take it on faith that you assign to money, the last, best, and final word on what is done or not done, on earth as it is in heaven. Tocqueville notices this in 1831—when he’s traveling around in Tennessee—that the Americans…he expected a turbulent, direct, forthright, argumentative people, and he was astonished to find how good they were at the art of civility, what he calls the “courtier spirit,” the bowing and scraping in nine directions, into the scent and wind of money. I mean, they’re like weather vanes or wind flags on sailing vessels. And he goes on to say that he never countered people so afraid of free expression, because they’re afraid of offending, of losing a scrap of advantage or a degree of self-importance. You see that all the time. I mean, I had a television show once in the 90s, about books. We’d have two or three authors discussing a book and argument was the idea. But none of the American authors would argue. I mean, in the green room, they were fierce. But as soon as the light goes on, it becomes a sort of ??

Robinson

I’m really glad you brought this up. There is more to the analysis that runs through your work than just money. You also talk about the elaborate social rules that have developed and that govern people’s interactions with us. I don’t want to give people the impression that your analysis is kind of like Marx or Milton Friedman, right? In fact, it’s quite different…

Lapham

No, no. I’m interested in the culture. Upton Sinclair talked about the pecuniary standards of culture that value a man’s excellence by the amount of other people’s happiness he can possess or destroy. I’m interested in that. I mean, I’m interested in what happens when you make your country the culture of business and business of culture. I mean, it’s an old argument. I mean, Edith Wharton makes the argument and so does Veblen. So, in part, does Tocqueville. How do we measure our happiness? I was reading a new book called The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow. I found it a marvelous book. They talk about the possibility of creating a complex society that is not based on money. And we’ve done it in the past. And they find an American Indian, Wyandotte, North Great Lakes, who knows this and who says this, makes a wonderful speech about money that could have come right out of the pages of my book. He’s an Indian who has been to Paris and is just appalled at how France arranges its whole society around money.

Robinson

I want to return to that point directly about the lack of confrontation. It’s a really interesting thing that I agree is an American quality. It’s another thing that I noticed in law school that I found eerie and strange, a kind of indirectness, a kind of unwillingness of people never to talk politics in law school. They never even talked about the law at law school. They only talked about their professors, their classes, their jobs. And I noticed this in graduate school, too. People never wanted to confront you directly; people don’t want to be impolite and don’t want to rock the boat. Lapham’s Rules of Influence book is a lot about the people you can criticize the people you can’t, how there is a delicacy with which you have to navigate the social world if you’re going to get ahead, the way that people flatter, the way that people suppress their real opinions, or real thoughts. The acceptable things to say and the unacceptable things to say.

Lapham

Yeah. During the 80s and 90s, I published eight or nine collections of essays. And I would occasionally make book tours. And I’d find myself in Denver or Seattle or Chicago. And I expected people to argue. I couldn’t believe it. I was saying things that were clearly against the rules. I expected a loud argument but got nothing. I was accepted as a kind of talk show guest or a visiting celebrity, and nobody wanted to engage. And you’re right. We still don’t engage in real arguments. We don’t engage about, why do countries go to war? Or, what is the objective of our system of education? Or, what do we mean by democracy? You’re right. The questions always come, you know, how much and if, or when, is the check in the mail?

Robinson

And you also talk about status, about these superficial markers—prizes, institutional affiliations. I deliberately mentioned in the introduction that you left Harper’s for a brief period in the 80s because there’s a story in Lapham’s Rules of Influence that I think is just hilarious. You’re invited to a fancy Council on Foreign Relations dinner, and you’ve lost your institutional affiliation. Suddenly, they’re horrified because they don’t know how you’re going to qualify to be at a fancy dinner.

Lapham

Yeah. You know, as if I ceased to exist. And that’s one of the differences. There’s nobody on earth that doesn’t believe in money, right? Americans are not unique in that, but what we are unique in is putting so much value into it. For example, the Washington swamp, right. The rotunda of lobbyist, politician, lawmaker to lobbyist, and back again and so on. Everybody wants to stay connected to some kind of institution. In England, people can afford to say what’s on their mind. And if they lose, okay, they can go back to the country. They have another identity that is not completely entwined in their institutional identity.

Robinson

One of the pieces of advice you offer in Lapham’s Rules of Influence is to make sure not to do a negative book review of any prominent authors. You really have to be careful not to fall out of favor. People will turn on you instantly. And you’ll be out of the proper circles.

Lapham

Yeah. Well, you see what’s happening. That book was written, I don’t remember how many years ago. But now with what we call cancel culture, it’s just gotten that much worse. People are afraid to say anything, because who knows what is going to be used against you? There’s a fine essay by Anne Applebaum in this month’s Atlantic which is called “The Last Puritan.” And she talks about the silence that’s imposed on people afraid to speak their minds. Afraid to, say, contradict the wisdom in office, whether it’s in a university or a bureaucracy or a corporation.

Robinson

I tend to be a little bit critical of some of the arguments like Applebaum’s. One of the reasons is, I think it collapses some of the distinctions between who you’re offending.

Lapham

Yeah. Okay.

Robinson

You have this anecdote about when Dan Rather was going to write critically about Richard Nixon, but then all of a sudden decided that he’d be better off inside the White House than out. So there’s silence because of corporations and the government, which is a little bit different to me than silence because it offends people who are interested in social justice…

Lapham

You’re right. I take your point. But I’m just talking about the audible silence.

Robinson

You must have seen, as a magazine editor, journalists deliberately pull their punches for career-based reasons or access-based reasons?

Lapham

Well, that’s the story of Rather, right? I remember I commissioned some kind of an essay. This was in the 70s. I was the managing editor commissioning an essay from a Time writer on some large trending topic, and he wrote it. In the last paragraph, he permitted him to say, “I think.” And when he saw it in the proof, he changed it to “millions of people think.” And I killed the article.

Robinson

This world of status-seeking and this need to constantly be focused on one’s career—how much does that, in publishing and journalism specifically, inhibit and keep us from having the kind of rich intellectual world of books and magazines that we might have if it were driven purely by intellectual concerns rather than commerce?

Lapham

Well, again, it’s what pays and what doesn’t pay. You don’t have to work for a newspaper very long to find out which stories make page one and what your editors want to hear. So there’s no room for that. There is informed and rich discussion in magazines of small circulation. But in large circulation, it’s not as common.

Robinson

Well, that’s why I’m very proud of Current Affairs, which has a small circulation.

Lapham

Yeah. I agree with you. I went to Cambridge. And E.M. Forster was still alive, and gave one lecture a year. And the first time, it was a regular ritual, that the date, time, and room of the lecture would be posted. And 150 people would show up. And Forster wouldn’t. It was posted a second time. And 50 people showed up. And Forster didn’t. The third time. Nine people showed up. Forster walked in, on time, and said, Good, now we can talk.

Robinson

I need to try that.

Lapham

Well, you’ll get the rich conversation. Yeah.

Robinson

Well, Lapham’s Rules of Influence, by the way, is extremely useful. When I was trying to sell a book, I was struck by the world of publishing and finding out just how much publishers buy. They don’t even really care what you put in the book. They care about whether the concept of the book matches what they sense will sell at that particular moment. And if you can convince them…I wrote a book on socialism, and the reason I was able to sell a book on socialism was because it was a moment. It was a market moment. But once I wrote the book, they barely looked at the manuscript. They were like, Oh, thanks for the manuscript. We’ll put it out. Yeah.

Lapham

Also, if you make a proposal, they look up your prior track record. How many hits do you have on…? I mean, they ask these kinds of questions before they offer you…

Robinson

Yeah. And they want to know how many social media followers you have. Do you have enough to..and if you say you have a lot…

Lapham

Well, that’s right. They want to find out whether you’re a marketable commodity.

Robinson

That’s exactly it.

Lapham

They don’t care about the ideas.

Robinson

It’s shameless. I resisted the urge to make my book an autobiography. But because autobiographies sell better than books about ideas, there’s this sense of, can you make this a story about you or about a different person? And what’s frustrating is that that is not done from the perspective of making the book better, but to give them an easier way to sell the book.

Lapham

I mean, that’s always the question. I mean, we are a plutocracy. That’s the question that gets asked. It’s the price of the thing, not the worth of the thing. That is the question that we ask. And we assign to money, the power of intellect and feeling and thought.

Robinson

Well, it’s always funny to me that Oscar Wilde said that a cynic was the person who knew the price of everything and the value of nothing. But actually, a modern economist quite literally believes that price is a genuine measure of value.

Lapham

Yes, we do. That’s how we value our baseball players and our movie stars and our handbags and our polo shirts. That’s the constant buying of self-esteem. Because to buy a polo shirt from Ralph Lauren, you could buy exactly the same polo shirt from an unknown sweatshop. But what you’re buying is the name and the privilege of wearing that name, which is therefore enhancing your own value.

Robinson

I don’t know if you’ve read about NFTs.

Lapham

No, I don’t know what that is.

Robinson

Well, this is the latest development, which is even further in that direction. You essentially buy a digital file. People spend millions of dollars and essentially they send you an image file and they say, this is yours. But the entire thing is about status. So people are spending millions of dollars on what is essentially nothing. It’s air. But it’s status.

Lapham

Yeah. I mean, that that’s the whole argument of Veblen, in The Theory of the Leisure Class.

Robinson

I do want to caution listeners. I said earlier that I follow Lapham’s Rules of Influence. But if they haven’t read Lapham’s Rules of Influence, they should know that they should not follow, under any circumstance, the rules. They are things like “practice your lies like you practice your golf swing.”

Lapham

Yeah. Right.

Robinson

You now edit your Quarterly. You pick a subject for each issue. And you mine the archives of history for fascinating lost texts and quotations and insights from the human intellect across times and cultures. It’s a really unique publication. In the course of your mining of the past, are there one or two things that you’ve come across that you feel really give a profound insight into the nature of this country that you’re glad you found and could share with the world?

Lapham

Well, I found a number of them. I look at the past as an immense storehouse of human consciousness. Over time and traveling across the frontiers of the millennia, men save what they find to be beautiful, useful, or true. So, these are navigational-like in the gulf of time. I think we have an enormous amount to learn from the past. I think the past is generative. It’s filled with wonders that we can use.

I’m reading The Dawn of Everything. The authors are an archaeologist and anthropologist. They’re ethnographers, and they’re seeing what they can learn from the history of the late Paleolithic and early Neolithic, and they are finding lost civilizations that achieved a great deal of…that were not only complicated and crowded and noisy civilizations but also allowed for the freedom of their citizens. They were leading lives without war, without Hobbes. That, to me, is enormously hopeful. I tell you what I find in doing the Quarterly. It’s exciting, because I’m always learning, and I’m astonished by the power of the human mind and imagination and the wealth of its expression. So if I’m learning to look at a painting by Goya for the first time or if I’m learning to read, for a third time, a novel by Melville or Balzac, I mean, it’s constantly opening doors and windows into what Will and Ariel Durant called “the celestial city of the past,” where sculptors still carve, musicians still sing. I mean, one of the things in giving up your whole mind and soul to money is that it shrivels your imagination, it brings it down to the abstraction of a price, instead of the richness of the thing itself.

That’s what’s remarkable about our current circumstances: the poverty of our imagination. We haven’t had a new political idea in 50 years. And the reason is that we talk about money, instead of about ideas, or feeling or emotion. Reading this book Dawn of Everything gives me reason to feel that men at one time had the imagination to create a future fit for human beings, instead of a future fit for machines, which is what we’ve got going now. I mean, the belief in money, like the belief in technology, in and of itself, is a revolution in the direction of the world made by and for machines. We have to figure out a way to make a future fit for human beings. And that is the problem that we’re confronting at the moment. And the more that we look for the answer in money, the less likely we are to find it.

Robinson

Well, I like what you’ve said. It’s not necessarily a hopeful, but also not a hopeless, note to end on. One of the reasons I think the loss of David Graeber is such a tragedy is that he was one of these real proud utopians who looked all around as an anthropologist and found all these possibilities for the human species. People might get the impression from picking up your books that you are a pessimist. So much of the books are about American democracy as theater, about hypocrisy, about selfishness, and about shallowness and flattery. But beneath that is a real belief in people and a real and deep love of what we are capable of, and of the cultural treasures that we’ve produced. The Ivy League schools, for example…my big disappointment is that you have the world’s most incredible libraries…you have everything here. And yet you’re talking about your jobs, your future job. You think, what a waste, what a colossal waste of human potential, and it comes out of a real real belief that we could be better than we are.

Lapham

There’s a book called Stover at Yale that was published in 1912 by a guy named Owen Johnson, and he says exactly what you just said. It’s weird. I mean, to read him, you would be talking to yourself, but it’s a wonderful thing. We’re doing another issue on education. And I have that passage in it from Stover at Yale. 1912. You know, it is a complete waste to spend all your time networking when you could be reading and talking. It’s true, I am hopeful. I’m not optimistic, but I’m hopeful.

Robinson

Well, thank you so much for joining me. This was a really delightful conversation that I had been looking forward to for a long time. The book Money and Class in America: Notes and Observations on Our Civil Religion was re-issued by OR Books with a new preface by the great Thomas Frank, who has been a guest on this program. And Verso also published Lewis Lapham’s Age of Folly.

Lapham

Thank you, Nathan. Thank you.