Medieval Dreams and Far Right Nightmares

The cultural obsession with the idea of the Middle Ages—rather than its historical reality—has led us all into perilous, right-wing realms.

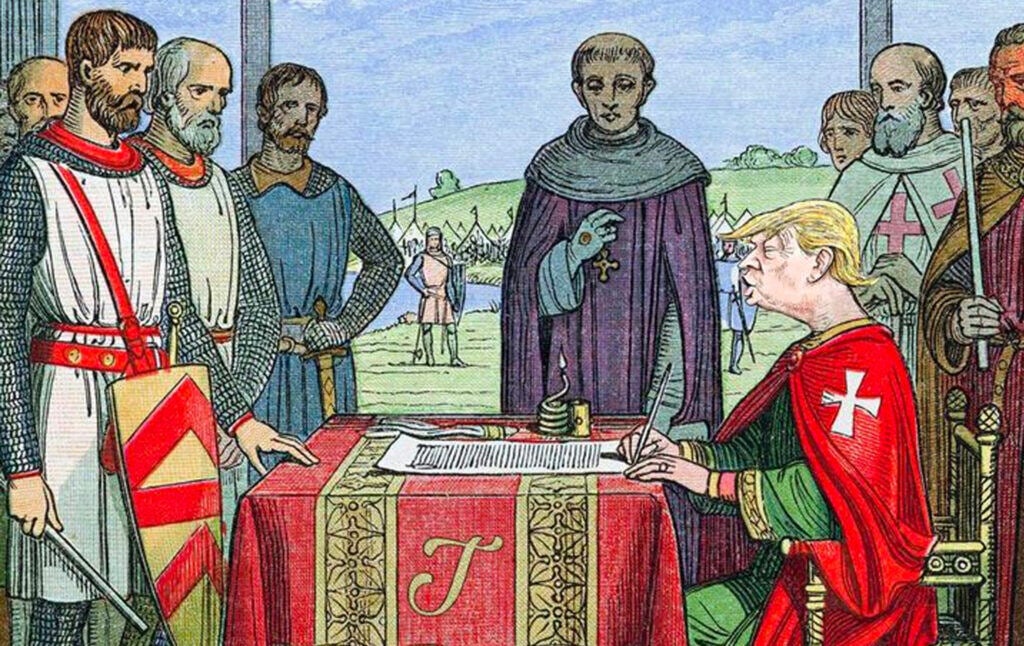

On April 16, 2021, the congresswoman, conspiracy theorist, and noted CrossFit enthusiast Marjorie Taylor Greene put out a memo outlining her plans for a new “America First Caucus.” This voting bloc was intended to pick up where former President Donald Trump had left off, fighting for the rights and privileges of white people who already have them. Within the seven absurd pages of this memo, there appears some positively medieval language: she calls the United States “a nation with a border, and a culture, strengthened by a common respect for uniquely Anglo-Saxon political traditions.” The term “Anglo-Saxon”—a dog-whistle that caught the attention of many on the left—has increasingly been condemned in Medieval Studies for being both anachronistic and profoundly problematic. Although the term itself was used sparingly in medieval England (appearing only three times in all surviving Old English literature), it was co-opted into early modern colonialist discourse to justify the superiority of the white race, and has a long history of use by far-right actors who glorify their own supposedly “Anglo-Saxon” past. As medieval scholar Mary Rambaran-Olm explained in a recent interview with Time: “It was always used for propaganda. It was always used for nationalist reasons.” Like so much of medieval history, art, and culture, the far right has taken the past, misunderstood it, and used it for their own purposes.

The modern obsession with the idea of the Middle Ages, or “medievalism,” has a long history in American culture that goes beyond drinking mead at a Renaissance Faire or smashing skulls in Skyrim. Medievalism refers to the afterlife of the Middle Ages, or how it’s been popularly reimagined by subsequent generations. (This is in contrast to Medieval Studies, which is the academic field studying the historical period known as the Middle Ages, as well as the later medievalisms it gave rise to.) Medievalism has a complex and often contradictory history that begins with 19th century romanticism and extends into the modern day. Regardless of whether the medieval is idealized as romantic and chivalric, or weaponized as a pejorative against “backward” cultures, public discourse around medieval imagery is disproportionately used to justify modern intolerance and violence. Most recently, the far right has rallied around the imagined brutality of the Middle Ages in order to legitimize their own ideologies, glamorizing “medieval” strongmen for fascistic purposes.

Over the past fifty years, researchers in the field of medieval history have analyzed an increasingly visible cultural obsession with the Middle Ages. Medieval scholar and novelist Umberto Eco described this phenomenon as far back as 1973 in his essay “Dreaming of the Middle Ages,” noting that medieval mania was especially well-suited to the United States: “a country able to produce Dianetics can do a lot with wash-and-wear sorcery and Holy Grail frappé.” This fascination has been fed by, and in turn contributed to, the prevalence of medieval-ish books, films, and role-playing games that pervade every library, bookstore, and streaming service. But recent events remind us that medievalism is hardly a harmless curiosity: for example, at the Charlottesville “Unite the Right Rally” in 2017, far-right rioters marched with medieval symbols from the Holy Roman Empire and Norse culture, chanting the crusader battle cry, Deus Vult (“God wills it”). Many medieval scholars reacted with horror and disbelief to this use of medieval imagery, even though scholars of color in the field had spent years attempting to call their attention to this kind of behavior in various contexts. Notably, medieval scholars of color such as Sierra Lomuto, Dorothy Kim, Cord Whitaker, and Mary Rambaran-Olm have examined the fascist and conservative use of the Middle Ages and medievalism. In their tracing of the history of medievalism, they draw us back to that breeding ground of modern intolerance: the 19th century.

PAST OBSESSIONS: SCOTT, KLAN, HITLER

Much of our obsession with the medieval past can be linked to Scottish novelist Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832). While Scott wrote historical romances in other periods, his most famous and (as we shall see) harmful creation was the medieval epic Ivanhoe, which weaves a narrative of chivalric knights fighting for love and honor in a heavily romanticized version of medieval England. Ivanhoe’s immense popularity helped fuel what scholars have called the “Medieval Revival,” an interest in medieval art and history that impacted elite culture in 19th century England by presenting a particular fantasy of medieval life. Some Victorian tryhards even attempted to revive the sport of jousting, and held a three-day tournament in 1839 to celebrate Queen Victoria’s coronation. The event was hindered by a tremendous rainstorm, and one can only imagine the rust and chafing that plagued many a would-be knight. Although the tournament was a “complete disaster,” historian Marcus Bull observed that it nevertheless demonstrates how Scott “made an enormous impact in raising the profile of the Middle Ages.”

To Scott’s readers, the Middle Ages were a simpler time when chivalrous, heroic men proved their worth in a violent and chaotic world by swinging sharp objects. Ivanhoe also imagines a medieval past that is explicitly racialized: as early as Chapter II, we encounter a Templar knight, Brian de Bois-Guilbert, commanding a battalion of dark-skinned slaves. This perfect blend of romanticism and racism would prove extremely popular in the United States—especially in the American South, where the image of the chivalric white knight played directly into the Southern gentry’s sense of racial and cultural superiority. Amy Kaufman and Paul Sturtevant’s book The Devil’s Historians describes how white Southern readers identified with the knightly figures in Scott’s novel, and viewed the Middle Ages as a period when noble lords justly held power over the lower classes. To the Southern aristocracy, the Middle Ages of Ivanhoe was a white utopia, and they embraced the supposed gallantry and brutality of this past in equal measure. As Kaufman and Sturtevant describe, “they whitewashed their enslavement of Africans as benevolent neomedieval lords” and even “challenged each other to duels, and jousted for entertainment.” This Southern “chivalry” drove Mark Twain to rail against Walter Scott in Life on the Mississippi, with all the passion and fury of a righteous Twitter cancellation: “He did measureless harm; more real and lasting harm, perhaps, than any other individual that ever wrote… Sir Walter had so large a hand in making Southern character, as it existed before the war, that he is in great measure responsible for the war.”

As Twain saw it, Scott had deepened the white Southern aristocracy’s obsession with class and rank through his glorification of an imagined medieval past. After the war, when Southern landowners clung to their notions of racial superiority in the face of newly-freed Black Americans, Southern medievalism was vital to the founding of the first “Knights of the Klu Klux Klan” in 1861. Portraying themselves as chivalric defenders of the white race, the organization adorned its highest members with explicitly medievalized titles like “dragon” and “wizard.” The Klan set the stage for how successive generations of American extremists would adopt and weaponize the trappings of medievalism.

The Klan was not alone in adopting knightly cosplay in service of their far-right ideologies: the Nazis also drew on the medieval past for inspiration. Hitler and Himmler obsessed over the Arthurian legends, the Knights Templar, and the Holy Grail. (Whether their Grail obsession also led to them tangling with a whipcracking American archaeologist and his inexplicably Scottish father must remain an open question). Himmler seems to have modeled his headquarters at Wewelsburg Castle in imitation of the Round Table. As scholars Fabian Link and Mark W. Hornburg note in an article, “Nazi ideologues also used medieval figures such as Henry I, Henry the Lion, and the Knights of the Teutonic Order to justify conquering territories in Eastern Europe.” The Third Reich used the imagery of medievalism to highlight the strength of the National Socialist movement, and portrayed the medieval period as a heroic past that demonstrated German might.

A particular fantasy of the medieval thus became entrenched in the far-right imagination as a time of racial and cultural purity that white European traditionalists could look back to with nostalgia. This fetishizing of the Middle Ages was, of course, a mere caricature of the actual human past, stripped of all complexity and nuance. Such thinking turns history into a blunt instrument, a weapon to be used against those who are Othered. The events of the early twenty-first century would see the Middle Ages weaponized yet again, in a slightly different way, this time as a xenophobic slur to hurl at America’s enemies.

9/11, THE WAR ON TERROR, AND MODERN MEDIEVAL COSPLAY

The destruction of the Twin Towers on September 11, 2001 opened up a Pandora’s Box of medievalism. Immediately following the attack, news outlets, particularly those with a conservative bent, began making references to the supposedly “medieval” qualities of the West’s enemies. On September 12, David Beers of Salon wrote that the United States was not as safe as it thought from enemies on the “still-medieval hinterlands.” Victor David Hanson of the National Review positioned the United States as in “an age-old fight against medieval foes who despise modernity, liberalism, and freedom.” Shortly afterwards, Joe Conason of the New York Observer remarked that these terrorists’ belief system was “medieval, opposed to progress in every sense.” One would be forgiven for thinking that terrorists had attacked the Twin Towers with a trebuchet.

The crusades, moreover, soon became the de facto metaphor for understanding the attack, compounding the growing Islamophobia that surged through a frightened American populace. Having denounced their enemies as “medieval foes” who despised American-style progress, thought leaders and politicians just as easily turned on a dime and began characterizing Americans as a “good” kind of medieval, the crusader knights who would bravely charge into battle against the Islamic world. That this paradigm made little actual sense obviously didn’t matter: the country seemed to be existentially threatened by a violent, unreasonable Other, encouraging a turn to an imagined past in order to fight it.

While George W. Bush’s infamous comment that “This crusade, this war on terrorism, is going to take a while,” is perhaps the best-remembered bit of 9/11 medievalism, this kind of thinking was profoundly embedded in conservative circles in a way that went well beyond Bush’s gaffes. In Neomedievalism, Neoconservatism, and the War on Terror, medieval scholar Bruce Holsinger explores how the Bush administration routinely called on medievalized and “neomedievalist” language in its effort to seize political power. “Neomedievalism” is a theory propagated in international relations, prophesying that world politics is heading towards a time when the nation-state will fail, and the population’s loyalty will transition to “supra-national” institutions that defy national boundaries, like the medieval church. Many conservative thinkers saw the Taliban and other Islamic extremists in this light, and likened them to “feudal lords.” Neoconservatives within the Bush administration, such as Donald Rumsfeld and Paul Wolfowitz, helped to spread this interpretation of the Middle East as a means of aggressively Othering the entire Islamic world as the enemy of the West. In turn, because these neoconservatives believed their enemies presented an existential threat to the nation-state—and indeed to the modern world itself—they behaved as though this gave them license to deal with them in similarly “medieval” ways, justifying a mad crusader-style grab for regional power and the use of torture against their adversaries.

This rhetoric outlasted the Bush years: throughout 2016, presidential candidate Donald Trump often likened violence in the Middle East to “medieval times.” (We must assume that he did not mean the restaurant.) Trump’s answer to this violence was to meet it head-on with equal aggression; to be just as “medieval.”

THE MODERN ALLURE OF MEDIEVALISM

This desire from the right to “go medieval” on their enemies increasingly catapulted medievalism into mainstream political discourse. Drawing on both older and more recent histories of fascist medievalisms, conservatives on the internet began imagining themselves (both “ironically” and not) as crusaders and other medieval strongmen. The same internet communities that fueled the rise of neo-conservatism and neo-fascism have offered a space for medieval mythmaking that escalates from crusader memes to real world violence. Much like the Klan, fascists and white supremacists happily adopt the trappings of Vikings, Templars, and other figures; it’s common to see any number of medieval appropriations at far-right rallies, mixed in with QAnon flags and Punisher t-shirts. The American Defense League’s “Hate on Display” website and an extensive Twitter thread by medieval scholar Mary Rambaran-Olm both catalog a staggering breadth of medieval imagery adopted by such groups. The use of these images and memes plays on what Andrew B.R. Elliott has termed “banal medievalism”: the creation of an idea of the medieval period through symbols and imagery that have little to do with the historical past.

The actual past, in all its complexity, is generally inconvenient for white supremacists. Genetic research shows that the Vikings were not blond-haired, blue-eyed supermen, but had a heterogenous genetic makeup which suggests cultural mingling and interchange. The European crusaders’ efforts to conquer and colonize the Middle East were all abject failures, thus making it not only immoral but idiotic to cite the crusades as evidence of “Western” superiority. The existence of actual research and evidence on these subjects, however, rarely carries weight in white supremacist circles: scholarly research is only interesting if it can be used or misused to support a pre-existing narrative about European superiority.

Fascism, of course, is particularly invested in myth, usually appealing to a legendary heroic past, rejecting the softness of modernity and aspiring to the strength of previous generations. The imagined brutality and violence of the Middle Ages is the perfect backdrop for fascist fictions. It helps that since the Early Modern period, the Middle Ages has often been portrayed as a regressive contrast to modernity, one that is simple at best and savage at worst.

And just as there was something attractive to 19th-century elites about the image of the chivalrous, virtuous knight who rightly held dominion over serfs and slaves, there is also something perversely compelling about what medieval scholar Christopher Bishop calls “dark medievalism.” This decidedly unromantic perspective on the medieval past caricatures it as a brutal historical fugue, filled only with callous, sadistic violence. Such an environment is a breeding ground for precisely the kind of strongmen that fascists worship, because they presume that only a real man could survive such a brutal world. Modern depictions of the medieval, such as Game of Thrones, play into these fantasies by emphasizing the “grittiness” of the period. Again, the fact that this is a fantasy makes no difference, as fascists often ignore or dismiss the intellectual inconsistencies in their own ideology. It is the supposed darkness of the “Dark Ages” that makes them so appealing to the modern far right.

One illustrative example of this phenomenon is the modern right’s frequent deployment of “Conan the Barbarian,” a character first created by Robert E. Howard in the 1930s. Conan the Cimmerian—a muscle-bound, sword-wielding barbarian—exists in the pseudo-medieval world of the Hyborian Age, situated between the mythic Fall of Atlantis and the founding of Rome, a kind of precursory “Dark Ages.” The black-haired and blue-eyed character himself hails from a tribe that the author frames as an ancestor to the Gaels. In the original stories, Conan adventures through various lands, “rescuing” damsels and battling vicious adversaries. His most enduring foes come from Stygia (supposedly Egypt), a land of seemingly unending quantities of snakes, plagues, curses, priests, narcotics, and sorcerers, who ritually sacrifice scantily-clad women. (Edward Said must be rolling in his grave from the sheer volume of Orientalizing tropes listed here.) Scholar Helen Young has noted that fantasy narratives suffer from “habits” that traditionally imagine the protagonist as a white paragon juxtaposed against villains who are not. Although this is surely not the only reason for Conan’s popularity writ large, users of extremist sites such as Stormfront have drawn plenty of inspiration from the racist aspects of Howard’s stories.

The allure of Howard’s work differs greatly from that of Scott, though they both draw from popular conceptions of a broadly Eurocentric medieval setting. While Ivanhoe celebrates the knight-errant struggling for king, country, and chivalry, the Conan stories dispense with such romanticisms to portray a dog-eat-dog world where might makes right. The various civilizations through which Conan travels tend to be characterized as weak, decadent, and unprepared to survive the violent and dangerous conflicts of their time. Indeed, Howard’s narrative moralizes Conan’s pure barbarity as superior to both the civilized (even if white) polities or the hybrid “mongrels” alike. The barbarian’s ability to overcome seemingly insurmountable foes in an era of violence and chaos perhaps appeals to the conversative values of rugged individualism and traditional gender roles.

Set against the backdrop of one man’s quests against hordes of recycled racialized enemies, the Conan narratives even draw upon notions of Manifest Destiny. From sea to shining sea, the barbarian conquers the lecherous Hyrkanians (Mongols), fraudulent Vendayans (Indians), sorcerous Stygians, bloodthirsty Picts, as well as the shifty Shemites and Black Cannibals of Darfar (these last two are among the most horrifyingly explicit racializations). Howard’s stories follow Conan from lowly thief, to mercenary, to frontiersman, and eventually king. Such social progressions are framed as justified and expected because of his ability to shape his environment by violently displacing those who “get in the way.” In doing so, the character often exudes an Ayn Rand-ian “Objectivism,” whereby the barbarian lives for himself, his own self-interest, and his particular morality, with only vague moments of honor to nuance him. Howard’s depiction of Conan embodies a kind of “Western Supremacy” that is accessible to white, able men, if only one has the wherewithal to forge it with steel, blood, and aggressive self-reliance.

MAGA culture has cast the now-former President in the role of Conan: one political cartoon produced on the right-wing blog “RedPillJew” imagines Trump with a Schwarzeneggerian physique, paying homage to the infamous lines from John Millius’ 1981 Conan the Barbarian film: “Crush your enemies. See them driven before you and hear the lamentations of their women.” Trump-Conan promises to actively undermine the first Black president and shame “Globalists” (a dog whistle for anti-Jewish conspiracy theories), while suggesting contempt for the “hysterical” nature of liberals. The cartoon reflects the weaponized dark medieval language deployed throughout the Trump administration. As the former president himself stated outside the White House on January 6th, “you’ll never take back your country with weakness. You have to show strength and you have to be strong.”

If the right-wing appropriation and obsession with the medieval ended with Conan memes and silly complaints about culture, then perhaps they could be considered peripheral. But they do not. The fascination with medieval European fantasy is present in online spaces that have proven to be breeding-grounds for real-life right-wing rallies, marches, and riots; it’s also present in spaces like the U.S. military, which holds much more immediate and tangible power throughout the world. Take the 2009 installation at Fort Hood of the statue known as the “Phantom Warrior,” the mascot for the III Army Corps.

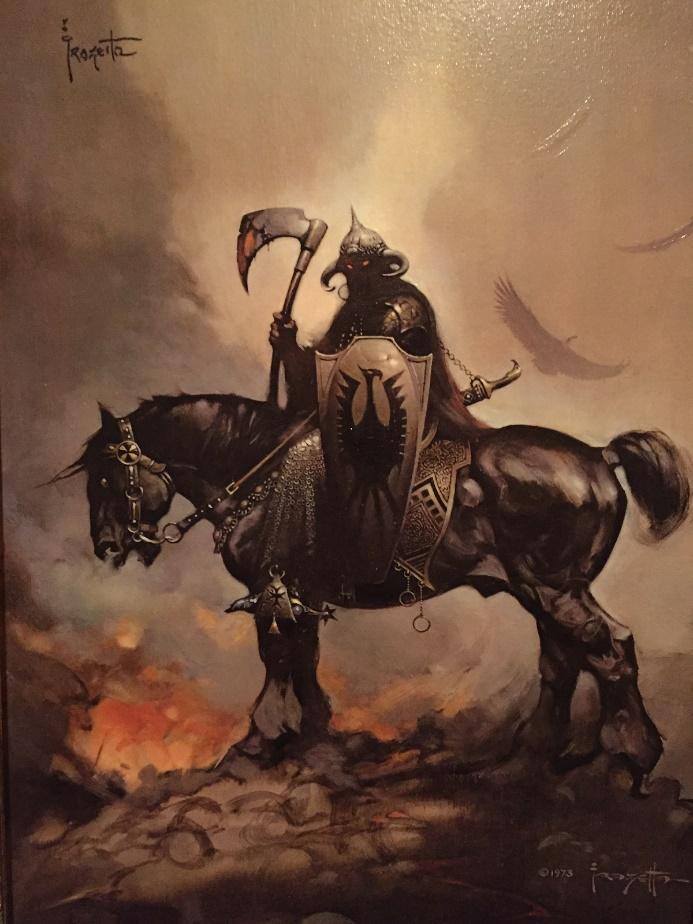

The “Phantom Warrior” is in fact an adaptation of a character from a 1973 painting by Frank Frazetta, the “Death Dealer,” showing a figure with a horned helmet, axe, and a shield bearing the Reichsadler, or German black eagle (which is replaced with the Corps’ caltrop insignia in the Foot Hood statue). Similar to Conan, the Death Dealer is coded as a white, “Viking,” Proto-European, hypermasculine barbarian, though he exists in a world even less nuanced than Howard’s character. The painting inspired the 1987 novel Prisoner of the Horned Helmet, where the character, here known as “Gath of Baal,” single-handedly defends a group of forest-dwelling white people from an army of yellow-skinned slavers and their Islamized allies. Gone now are the decadent white civilizations of the Hyborian Age: this world is shown as a simple dichotomy where “Eastern” incursions threaten a “Western” frontier.

So, what does it matter if a division of the United States military decided to adopt a bizarre icon of 1980s sword and sorcery? Iconography is important to the public: if it were not, then defenders of Confederate monuments wouldn’t bemoan the loss of their “history,” nor would Black Lives Matter protestors cheer at these monuments’ dismantlement. According to the Army’s own literature, the “Phantom Warrior” statue was meant to “reinforce and reinvigorate the image identity of the heavy maneuver force to its soldiers.” In no uncertain terms, the military recognizes that iconography informs values. But if the statue inspires military prowess, then it simultaneously references and idolizes a bizarre fantasy about medieval Europe.

The implications of this work of art and its placement are striking and troubling. This symbol of an important Army formation, situated at a base named for a Confederate general, fetishizes a white hero who slaughters racialized outsiders to defend the homeland. Given the growing problem of white nationalist groups in the U.S., and the disproportionate number of former military personnel at the Capitol riots—not to mention the problem of white supremacy in the police and military writ large—we should at least wonder at what values such visual programs engender. The truly terrifying part of the right-wing appropriation of the medieval is not when nutjobs decide to roleplay barbarians, but the realization that U.S. military propaganda enshrines such imaginings in the first place. A military genuinely concerned about the possibility of “domestic terrorism” would not, one assumes, glamorize anti-democratic strongmen like the Death Dealer. Like the Islamophobia that pervaded the Bush administration, seemingly incidental medievalism reveals a far more nefarious truth about the extent to which medieval imagery affects contemporary conservative politics.

MANAGING THE MEDIEVAL

The far right’s use of medieval history and medievalism should be troubling for everyone who seeks to live in a just, inclusive, well-functioning representational democracy. For more than a century now, conservative extremists and white supremacists have looked back upon an imagined version of the distant past to valorize their behavior. Building upon already politicized and identarian understandings of the Middle Ages, these groups cling desperately to a fractured vision of the past and reduce a millennium of complex history into a parody of itself. The far right seeks to claim the Middle Ages as its own, but a historical period is not a slogan or propaganda. It does not belong to the right, or the left, and certainly not to the white race. The Middle Ages do not belong to anyone. Yet because of its racist baggage, it must be managed by everyone.

In this respect, medieval scholars as a field have much to learn. As medieval scholar Sierra Lomuto has noted, there are no “innocent medievalists” whose scholarly interests have been suddenly and unexpectedly utilized by Nazis: the academic discipline of medieval studies has historically centered narrowly on a European (and particularly a Western European) geographic focus, used Eurocentric benchmarks for historical periodization, excluded non-European and non-Christian cultures as irrelevant or incidental to their narratives, and generally foregrounded European history in ways that contribute to white supremacist narratives and ideologies. Only over the past several years has Medieval Studies begun to wrestle with the long-unacknowledged racism within the field. Examples range from the revelation that prominent scholars are aligned with the alt-right propaganda machine (such as Professor Rachel Fulton Brown of the University of Chicago, later appointed by President Trump to his Cultural Property Advisory Committee), to the resistance to retiring the misnamed (and racist) sub-field of “Anglo-Saxon Studies.” Failing to address these issues with the discipline will only continue to make medieval scholars of color feel isolated and unwelcome, and lead to a less vibrant and interesting study of the past. It is also worth noting that the issues of nationalistic appropriation of the medieval past do not end with the “West” and have implications for the rise of fascist ideologies in other parts of the world. For example, the 2018 Hindi film Padmaavat depicts a medievalized Indian (Hindu) kingdom besieged by a particularly treacherous, dishonorable, and rapacious Islamic ruler. Evidently, both European and non-European countries can employ fantastical pasts to promote notions of cultural and religious homogeneity.

Understanding the way the past can be used to prop up a racist and fascistic ideology can better prepare us to combat it. If fascism attempts to simplify and smooth over the complexities and inconsistencies of history, then it is our responsibility to call attention to them. The Middle Ages was a harsh and often brutal time which informed modern constructions of race, yet it also saw a flourishing of art and culture that can still move us after hundreds of years, and innovations in science and technology that revolutionized the global discourse. Its complexity and richness—its beauties and horrors alike—should be accessible to all for interest and study, and not partitioned away for the fascist fetishizing of the far right. Examples of what this reclamation of the medieval past and imagery might look like include the current translation project seeking to render Beowulf into every language, authors like N.K. Jemisin helping to upend the general whiteness of the fantasy genre, and A24’s new film Gawain and the Green Knight starring Dev Patel in defiance of the rigid expectations of whiteness in Medieval Europe. Such projects, from both academia and popular media, help to demonstrate that popular medievalism does not have to reify racial stereotypes and bolster modern imperialist fantasies. Perhaps we will never stop dreaming of the Middle Ages, as Umberto Eco would say—but we should be able to tell which are the dreams and which are the nightmares.

For a full list of the sources used for this article, please see this Works Cited page.

_(20145706174)%20(1).jpg?width=352&name=Berea_College_20101122_FoodService_LK(23)_(20145706174)%20(1).jpg)