How The Titanic Haunts Us

We have good reason to remember the story of what happened to hubristic rich people, and the imprisoned poor, in an enormous opulent floating palace.

As a little boy growing up in Florida, I went through a “Titanic” phase. I don’t remember how I became obsessed with the disaster, but I remember spending long hours reading about it, thinking about it, and playing a computer game called Titanic: Adventure Out of Time in which you explored a realistic simulation of the ship, meeting various eccentric passengers and crew, and trying to solve a mystery before everybody drowned. I also convinced my parents to take me to Titanic: The Experience, a museum in Orlando that recreated bits of the ship and featured rescued artifacts ranging from a wooden deck chair to the jewelry and combs of first-class passengers. (Today, the museum offers a 3-hour “First Class Dinner Gala” where you can reenact the experience of having a four-course meal as it would have been eaten in 1912, alongside actors playing Titanic captain Edward Smith and “Unsinkable” Molly Brown. Its gift shop offers Titanic hip flasks, Titanic socks, Titanic cufflinks, authentic Titanic coal in a commemorative case, replicas of the first class salad plates, Titanic Christmas tree ornaments, Titanic paperweight with miniature iceberg, replicas of historical newspapers from the day, a children’s book called Travis The Time Traveler and the Terrifying Titanic, Titanic word search and coloring books, and a plush teddy bear wearing Captain Smith’s uniform.)

I look back on my Titanic period and think of it as a little weird, like a child getting into the Hiroshima bombing or the Tenerife airport disaster. But of course, there are plenty who share the fascination—a 2.5 hour YouTube video showing an animation of the Titanic sinking in real time has over 70,000,000 views. (“WHY THE HEEL [sic] AM I SO OBSESSED WITH THIS F****G SHIP” reads one comment.) The volume of books and articles available is staggering; today one can even read individual accounts of what happened in each of the Titanic’s 20 different lifeboats.

Immediately after the sinking in 1912, a Titanic pop culture industry sprang up. In the months afterward, people could not stop writing poems about the Titanic, to the point where the New York Times felt the need to warn “that to write about the Titanic a poem worth printing requires that the author should have something more than paper, pencil, and a strong feeling that the disaster was a terrible one.” Films about the event were being made within a month, songs like “My Sweetheart Went Down with the Ship” were released, and many cinemas were controversially showing fake footage purporting to be of the sinking (at least one riot resulted from the fraud).

Over the next hundred years, there would be novels, musical compositions, and movies including a 1943 Nazi propaganda film and the 1964 musical comedy The Unsinkable Molly Brown. The grandest recreation of them all, 1997’s 3.5 hour melodrama Titanic was, of course, an unprecedented box office success, being the first film to gross over a billion dollars and winning 11 Academy Awards. Today, Las Vegas has its own 25,000 square foot Titanic artifact and replica exhibit at the Luxor Hotel and Casino, at which visitors “receive a replica boarding pass, assume the role of a passenger and follow a chronological journey through life on Titanic.” It features salvaged relics including “luggage, china, pots and pans, floor tiles from the first-class smoking room, a window frame from the Verandah Café, an unopened bottle of champagne with a 1900 vintage, and more.” It also boasts “the largest piece of Titanic ever recovered—a 15-ton piece of the Ship’s hull, a full-scale re-creation of the Grand Staircase as well as an outer Promenade Deck, complete with the frigid temperatures felt on that fateful April night.”

Yet another Titanic tourist attraction, with locations in both Pigeon Forge and Branson, promises the chance to:

- Walk the $1 Million exact replica of Titanic’s Grand Staircase

- Touch an iceberg and feel 28-degree water

- Shovel “coal” in Titanic’s Boiler Room

- Learn how to send an SOS distress signal

- Experience the Sloping Decks of the ship’s stern as she descended

- Sit in an actual size lifeboat and hear true passenger stories

- Visit Tot-Titanic – an interactive area for young guests 8 and under

- Discover your passenger’s fate in the Titanic Memorial Room

The Tennessee Titanic recreated a chunk of the ship’s bow at a cost of over $20 million and offers itself for weddings, birthdays, and corporate events. (“Outside Is Just The Tip Of The Iceberg!” it boasts.) I can’t help but find it a little creepy to make an upbeat attraction out of a horrible human tragedy in which people watched their families die. But part of me also wants to touch that iceberg.

Perhaps the weirdest bit of Titanic nostalgia is the ongoing project to build a duplicate ship, “Titanic II,” so that people can have as close to the full Titanic experience as possible (without the part where everyone dies horribly in the icy north Atlantic, one presumes). Titanic II is a pet project of a demented Australian mining billionaire named Clive Palmer, who has previously attracted notice for trying to build his own “Jurassic Park” of animatronic dinosaurs and for accusing the CIA of collaborating with the Australian Green Party to try to destroy his coal ventures. (Definitely a guy whose Titanic replica I’d feel secure sailing on.) The “Titanic II” project, which has been called crass and insensitive (including by a group called the Titanic International Society), appears to have stalled for the moment, but I have no doubt that if Palmer is sufficiently deranged, he will be able to pull it off.

The lasting presence of the Titanic in what is called the “popular imagination” is not especially difficult to explain. It was the largest ship of its time, and (at least in first class) was a magnificent floating chateau. Promotional brochures boasted that once one left the deck and stepped inside, “we at once lose the feeling that we are on board a ship, and seem instead to be entering the hall of some great house on shore.” Even today, its iconic Grand Staircase still appears grand. The smoking rooms, libraries, cafes, and squash courts were lifted straight from a British country estate—which is why aristocrats of the day paid the equivalent of over $100,000 in today’s money to secure the finest staterooms.

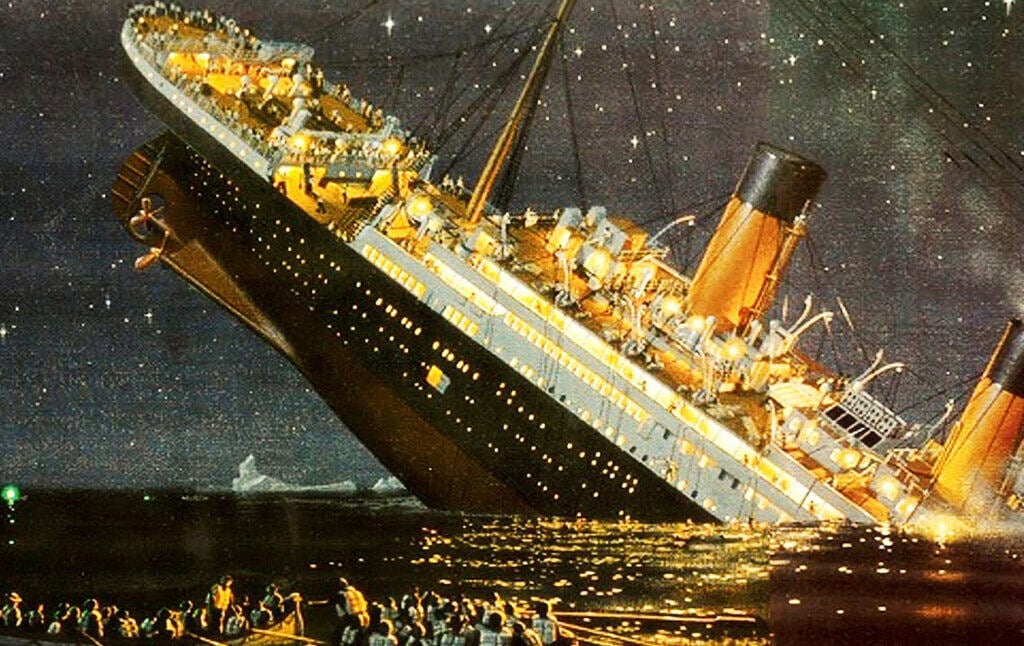

We can see why the images of the tragedy have staying power. All of this luxury and elegance seems so secure, so permanent. We are not used to seeing the most elaborate creations of the rich destroyed in an instant. There is something absurd in the juxtaposition of a finely-carved oak balustrade (and gold cherub statue) being violently consumed by the sea. The illusion that money can buy complete stability and control over nature is shattered. The millionaires in their smoking jackets, who seemed to have everything, rode their opulent pleasure palace to the sea floor.

The Chicago Daily Socialist, immediately after the tragedy, discussed the way it had forced the world “to consider the failure of a social system which does not first protect human life.” The Daily Socialist argued that the fact that rich and poor alike went down with the ship should show us that our social system serves no one and will destroy us in the end:

“Seated side by side, suffering from cold, sickness, horror and grief, sat the bride of a millionaire and the servant, the society queen and the migrant mother with her babe in her arms. Standing on the deck, waiting for the final plunge into the darkness, stood the millionaire idler, who, all his life, had collected the profits of the rush and hurry of labor. With him in that awful plunge went hundreds of workers, wringing their knotted hands in that last agony. Not all the millions of profits wrung from their labor and collected by the system for him would have the slightest power in saving either. Wealth plunged to the bottom of the sea, money, bonds, and securities, products of human skill and labor. Jewels to the value of millions glitter tonight deep in the Atlantic’s cold waters. But greater than wealth or the value of jewels are the lives of rich and poor, of the known and unknown human beings who were sacrificed on the Titanic in the fog of a black winter’s night to the god of the profit system in the mad fanaticism of speed.”

Of course, it wasn’t exactly a story of the robber barons realizing money can’t tame the wrath of Poseidon. Ruling class notables like John Jacob Astor and Benjamin Guggenheim might have perished, but the third-class passengers had it far worse. Three-quarters of the steerage class died, partly since grilled gates had been installed to keep the riffraff from accessing the upper decks, and the crew weren’t about to let them out when they would have competed for precious lifeboat space. The Marxist Daniel DeLeon said that the differences in the deaths of the poor and rich showed “the modern ocean steamship as the condensed picture of modern society.”

The grotesque differences between life on the upper and lower decks before and during the tragedy are vividly dramatized in the 1997 James Cameron film, which is remarkable for putting class differences at the center of its narrative. Cameron’s Titanic, telling the story of a fictitious romance between Rose the socialite from the first-class cabins and Jack the poor artist in steerage, may actually be the most Marxist film of the 90s. It is certainly one of the only major pop culture objects from the Clinton years to starkly portray the inhumanity of the class system. In fact, it’s almost too crude and cartoonish: the poor are cheerful, noble, and overflowing with culture, while the rich are mostly repulsive and out-of-touch. (Rose’s industrialist fiancé calls Jack “filth” and declares flatly that “We are royalty.”) But if you want a film that shows as bluntly as possible why wealth inequality is disgusting,Titanic, with its dancing proletarians and snooty bourgeois, could in parts have been scripted by the Industrial Workers of the World.

The class divide was real, of course. But one of the reasons the disaster has had such lasting cultural resonance is that it offers many other possible “lessons” as well. As the (excellent) Wikipedia article on the ship’s pop culture afterlife notes, the sinking was uncommonly like some kind of morality play:

“[The Titanic has been seen as] somewhere between a Greek and an Elizabethan tragedy; the theme of hubris, in the form of wealth and vaingloriousness, meeting an indifferent Fate in a final catastrophe is very much one that is drawn from classical Greek tragedies. The story also matches the template for Elizabethan tragedians with its episodes of heroism, comedy, irony, sentimentality and ultimately tragedy. In short, the fact that the story can so easily be seen as fitting an established dramatic template has made it hard not to interpret it that way… The disaster has been called ‘an event that in its tragic, clockwork-like certainty stopped time and became a haunting metaphor’—not just one metaphor but many… ‘conflicting metaphors, each vying to define the disaster’s broader social and political significance, to insist that here was the true meaning, the real lesson.’ … Some viewed it in religious terms as a metaphor for divine judgement over what they saw as the greed, pride and luxury on display in the ship. Others interpreted it as a display of Christian morality and self-sacrifice among those who stayed aboard so that women and children might escape. It could be seen in social terms as conveying messages about class or gender relations… Such a wide range of interpretations has ensured that the disaster has been the subject of popular debate and fascination for decades.”

The disaster was so ready-made for storytelling that it even lasted the length of a stage drama, about two hours from the encounter with the iceberg to the moment when it snapped in two and disappeared. (A ship that sinks in 15 minutes, like the SS Eastland in Chicago, does not afford those cinema-ready moments like the gentlemen donning their eveningwear and putting flowers in their buttonholes so they can go down in style.) It was that rare real-world event that didn’t need to be embellished for the screen. The best Titanic film, 1958’s A Night To Remember, sticks almost completely to historical fact: it simply depicts what happened, as it happened, no contrived love story necessary. The ship sinks, the evacuation is chaos, some people get off, some people do not. The result is riveting and chilling.

There is a certain “choose your own moral” to the Titanic story, then. There was even a distinctively Black take on the Titanic disaster, as Henry Louis Gates documents. Black newspapers saw the sinking as the logical consequence of hubris and overconfidence on the part of a white racist society, and tall tales developed about a legendary Black man named Shine who served as a stoker on the ship and swims safely to shore, having declined to save the millionaires despite being offered sex and jewelry. (The lyrics are fantastic.) After racing a shark to Harlem, he gets drunk in a bar as the white people ascend to Heaven. (It was widely believed at the time that there had been no Black passengers on the Titanic, but it has since been discovered that a Haitian engineer and his two daughters were in a second-class cabin.)

But even if everyone sees the story they want to see in the Titanic (the Christians saw good Christian morality at work, the rich saw noblesse oblige and dignity, the socialists saw the class system, African Americans saw white folly), certain lessons are undeniable. It did show unbelievable hubris and arrogance. Contrary to popular belief, the ship’s operator, the White Star Line, had never explicitly advertised the Titanic as “unsinkable”—public statements had always been qualified, like virtually unsinkable, or as close to unsinkable as modern engineering permits, i.e. not actually unsinkable. But it certainly hadn’t considered what ultimately happened to be within the realm of realistic possibility. Looking back, though, it’s somewhat incredible that the Titanic disaster was not foreseen. (It was, in fact, so easy to foresee that a decade earlier there had been a novel published about a ship called the Titan that, without carrying enough lifeboats for all passengers, hits an iceberg and sinks.)

The Titanic was not just “sinkable,” but extremely easy to sink—it “went down like the frailest shell,” as the Daily Socialist memorably put it. Remember what happened: Titanic essentially grazed an iceberg, but the impact opened up multiple holes along a 300-foot stretch of the starboard side of the hull. Six of the ship’s sixteen forward watertight compartments were quickly filled, which dragged the ship down and filled the rest of it. How could such a possibility have been overlooked? The Titanic was plowing along at full speed on a moonless night through a stretch of ocean known as “Iceberg Alley.” Messages from other ships warning of icebergs had been received all day—at one point, the Titanic’s wireless operator grew tired of them and replied “Shut up! Shut up!” in Morse code. (The respondent not only shut up, but went to bed, meaning that a ship that could have come to Titanic’s aid never received its distress signals.) When the sun rose on the survivors, one of the first things they noticed was that the area was absolutely full of icebergs (“There appeared what seemed to us, an enormous fleet of yachts, with their glistening sails all spread. As the sun grew brighter they seemed to sparkle with innumerable diamonds. They were icebergs.”) If it hadn’t hit the one it did, it could easily have scraped another.

How could anyone have thought this was reasonable, then? To go full steam ahead into “Iceberg Alley” in the middle of the night? Why did anyone think it was “unsinkable”? Had nobody considered the possibility of bumping into an iceberg in the pitch blackness of Iceberg Alley? And what was the theory behind keeping only a small number of lifeboats? Why was it just assumed nothing too terrible would ever happen? It all seems so insane in retrospect. The 1,500 people who died on the Titanic died for no good reason; there was plenty of time to evacuate the ship, but safety had evidently barely even crossed the minds of the shipping company executives, who were more concerned with features that would allow for promotional brochure copy like this:

“In the middle of the hall rises a gracefully curving staircase, its balustrade supported by light scrollwork of iron with occasional touches of bronze, in the form of flowers and foliage. Above all a great dome of iron and glass throws a flood of light down the stairway, and on the landing beneath it a great carved panel gives its note of richness to the otherwise plain and massive construction of the wall. The panel contains a clock, on either side of which is a female figure, the whole symbolizing Honour and Glory crowning Time. Looking over the balustrade, we see the stairs descending to many floors below, and on turning aside we find we may be spared the labour of mounting or descending by entering one of the smoothly-gliding elevators which bear us quickly to any other of the numerous floors of the ship we may wish to visit. The staircase is one of the principal features of the ship, and will be greatly admired as being, without doubt, the finest piece of workmanship of its kind afloat.”

Soon it was being admired as the finest piece of workmanship of its kind at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. The drama aside, what we can certainly see in the Titanic catastrophe is that it’s very easy for extremely skilled and talented people to also be utterly and completely delusional. The Titanic was an absolute engineering marvel, so much so that it still impresses us, even as cruise ships have grown much larger. It was the product of brilliant minds. But we can see that technical proficiency is useful only in the limited domains where it is applied, and if you spend all your time trying to answer the question “How do we give passengers the most astonishing luxury imaginable?” and none of your time answering the question “What happens if we encounter a piece of ice in the icy sea?” the result may be that a lot of people die painfully in a sumptuously-decorated smoking room.

The Titanic catastrophe actually makes me think of the folly of war, which involves a similar mix of engineering triumph and human tragedy. The development of nuclear weapons, which are amazing products of scientific insight designed to obliterate entire cities, shows that we can conquer incredibly daunting technical challenges while being totally unable to solve seemingly much simpler problems. That is, we can solve the problem of how to kill each other extremely efficiently, while being unable to solve the problem of how to keep ourselves from trying to figure out new ways to kill each other. In both the cases of war and the case of the Titanic, we find that human reason succeeds at the tasks it sets itself to solve, but that everything depends on which task we decide to solve. If we decide to solve the problem of how to make sure everyone on a ship can get off quickly, we will easily be able to do it. If we don’t do that, and solve the problem of how to make the world’s most impressive floating staircase, then that is what we will accomplish. If we decide to solve the problem of how to incinerate a city efficiently, we will certainly come up with an efficient method. But our time would be better spent trying to solve the problem of achieving permanent peace.

The good news, as I am sure you can see, is that this offers a somewhat hopeful prospect for humanity in a certain way. It suggests that our sustained effort can produce miracles, but that we need to be conscientious about what our efforts are put towards, account for bad incentives, and try to make sure we don’t have enormous stupid blind spots that will result in our downfall. This is not necessarily that difficult; as soon as the Titanic sank, safety measures that would have prevented the catastrophe were put in place. But one thing we absolutely depend on is independent critical judgment. It is easy for insanity to continue so long as nobody is questioning it. I am certain there were people within the White Star Line who wondered whether it was a good idea to send a ship into the middle of the frozen sea with more people than lifeboat space, but they were not loud enough in their objections. It is also easy to assume that confident authority figures must know what they are doing, and that if they seem to have overlooked something extremely obvious, it must be that they have good reasons. Captain Smith of the Titanic was highly experienced and respected (so was KLM’s captain Jacob Veldhuyzen van Zanten, who caused the Tenerife airport disaster). He looked like a reliable and sound-minded sea captain. And yet he was stupid: he not only whacked his ship right into one of the icebergs he had been repeatedly warned about, but he was incapable of organizing an orderly evacuation, meaning that a bunch of lifeboats were left half-empty and far more people drowned than needed to. The aesthetics of competence were all present, but actual competence is a process rather than a set of brass buttons and a white hat.

The Grand Staircase was itself part of the problem. It provided the illusion of stability, the classic “false sense of security.” From an engineering perspective, the Titanic was an incredibly fragile vessel that could easily be destroyed, but it is easy to lapse into subconsciously thinking something like: “Staircases so grand are found in stable and permanent places, it is unimaginable that such a staircase would be swallowed by the sea, thus this staircase will not be swallowed by the sea.” It is the same kind of thinking, incidentally, that led so many people to be surprised when Donald Trump won the 2016 presidential election. The actual facts showed that it was easy for Trump to win, and that the election was going to be close. But Trump winning was unthinkable. People like that do not become president, thus he could not become president.

We have to be careful, then, because over the last 100 years, we may have learned more about how to keep passengers on cruise ships safe (Step 1: sufficient numbers of lifeboats), but we are not necessarily much better at distinguishing the theater of logic and reasonableness from the real thing. The Titanic is indeed a valuable cautionary tale, and it is a shame that the disaster has been commodified and turned into a Vegas attraction and a bunch of souvenir kitsch (will 9/11 go the same way a century from now?). It is a sad and absurd event worth reflecting on, because it is a reminder not only that the class system is an abomination, but that rich elites can be utterly delusional about their own reasonableness, and that which seems most secure and permanent can actually be extremely vulnerable. We need to make sure our own highly unequal age of luxury and technology is not on its own doomed voyage. The eerie wreck 2.5 miles below the surface of the Atlantic, where plates are still stacked waiting for a meal that will never come, shows where those who overestimate their competence can end up.