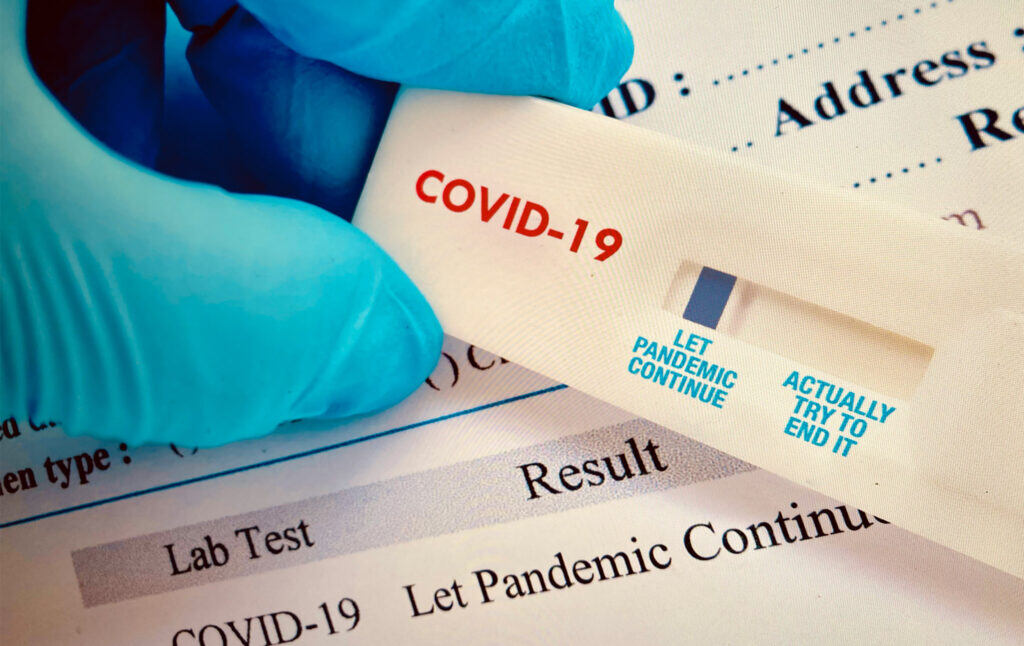

Continuing the Pandemic is a Choice

The United States has not seriously tried to end the pandemic. But failed institutions are not inevitable. The solution lies in human agency, solidarity, and political will.

As the pandemic drags on in its second year, we’re all wondering, When is this going to end? How is this going to end? Will things be like this forever?

As of early October, the U.S. daily death count is dropping but averaging close to 2,000 per day, a curve that looks similar to last spring—when death counts were considered shocking and the country was in the midst of a shutdown because it was considered too dangerous for people to be out in public. Yet we have many public health interventions to help stop the spread of the virus that we aren’t using effectively or at all. We aren’t acting like a country that is trying to end the pandemic.

In fact, our leaders keep making decisions that prolong this nightmare. Consider everything that could be done that isn’t being done. We still lack any federally coordinated comprehensive public health strategy to rapid test, monitor infections, contact trace, isolate/quarantine, provide masks and enforce masking, assist public places with HEPA filtration and ventilation, ensure vaccine equity, or mobilize a public health education campaign to educate people on the virus and mitigation measures, and to target, specifically, anti-vax, antiscience, and “health freedom” rhetoric, as well as to address genuine vaccine “hesitancy.” We have weak OSHA workplace COVID protections, ensuring that vulnerable workers in meatpacking, agriculture, and grocery stores remain at risk. FDA regulatory procedures have effectively prevented more widespread use of rapid testing. The reluctance to trample on “states’ rights” has permitted state leaders to actively work against common sense public health measures such as masking. Then there’s the global north’s vaccine apartheid, which ensures that poorer nations cannot effectively immunize their people, a situation that gives the virus even more chance to spread (and new variants to emerge).

Of course, if we were thinking seriously about putting all the options on the table, we’d think bigger. The need for Medicare For All, for instance, has never been more obvious: if healthcare is free at point of use, and people don’t have to navigate expensive and confusing private insurance systems, they will be better able to take care of their medical needs, and thus less vulnerable to deadly viruses. Decarceration—getting as many people out of jails, prisons, and detention centers as possible—reduces the enormous number of cases that occur because of transmission in these institutions. (And tragic stories like that of Nickolas Lee.) Guaranteeing people basic housing eliminates the spread that occurs among the homeless population. Guaranteeing paid sick leave means that people are less likely to come to work sick. (Instead of simply introducing universal paid sick leave like other developed countries, the United States introduced a confusing set of policies including mandatory paid sick leave applicable to certain employers through the end of 2020—a provision less than half of workers even knew about—along with a tax credit for certain small businesses that chose to provide sick leave. Biden’s American Rescue Plan of 2021 extended the paid sick leave provision but made it optional and only for certain businesses to claim a tax credit. Many workers still face a choice between coming to work infectious and losing their paycheck).

It is not terribly difficult to predict where we’re headed. If we keep doing what we have been doing, the pandemic will continue to drag on, risking new variants (viruses mutate, or change, and mutations create new variants), more people will suffer and die, more people will develop chronic conditions such as Long-COVID or other yet-to-be described complications (viruses, like other infectious agents, can cause all kinds of chronic health problems), and all the social problems that have been amplified by the pandemic will continue.

But it doesn’t need to be this way. The problem is not that cases cannot be significantly reduced, but that there isn’t the political will to entertain the real solutions. The pandemic is a policy choice.

Instead of looking seriously at all the options for getting cases down, the U.S. has been promoting a vaccine-centric strategy that shames and blames unvaccinated people for the continuation of the pandemic. Officials and the media have continued to declare that the “most effective” way to stop the virus is for people to get vaccinated. In late July, the New York Times wrote that the “only sure strategy for beating back the virus is getting more people vaccinated.” Despite the summer outbreaks among immunized people that led to the CDC’s mask policy update, vaccination continues to be the main focus of the discourse, with officials such as CDC Director Rochelle Walensky and President Biden saying we have a “pandemic of the unvaccinated.” (While it is true that the majority of severe illnesses and deaths from Delta are among the unvaccinated, the idea that an airborne virus affects only unvaccinated people is absurd.) Other officials have also blamed unvaccinated people for the rise of the Delta variant, a narrative promoted by some journalists while others merely focus on why so many people remain unvaccinated. (President Biden even partly blamed the unvaccinated for the “surprisingly weak jobs report.”) The White House’s latest pandemic plan mentions multiple strategies, yet puts vaccination at the top of the priority list and discusses masks and testing as useful because it will “take time” for vaccination to kick in, thus re-affirming the primacy of vaccination.

But we need to put vaccines into perspective. Vaccines have long been considered one of public health’s greatest achievements worldwide. Because of vaccines, every year people of all ages are spared serious illness, hospitalization, and death from infectious diseases ranging from viral diarrhea to hepatitis to the seasonal flu. Vaccination has eliminated polio in the U.S. (cases continue to occur in the global south) and smallpox. Indeed, COVID-19 vaccines helped U.S. COVID-19 case levels drop substantially prior to the rise of Delta and have saved countless people from severe illness or death (which, in turn, helps keep healthcare facilities from being overwhelmed by sick people).

Our current narrative around vaccination, however, fails to point out the challenges presented by vaccines. The protection offered by vaccines has been shown to wane over time, thus prompting the CDC to recommend boosters for certain groups of people. Boosters mean more vaccines must be produced, at further expense. Other variants of concern may continue to emerge, against which current vaccines (or natural immunity from having gotten COVID-19) may or may not be effective. We also do not know whether vaccination prevents Long-COVID in those who still get infected with the virus.

Vaccination can help reduce the spread of the virus, but only to a point. As epidemiologist and immunologist Michael Mina has explained, the current COVID-19 vaccines do not provide “sterilizing immunity.” In other words, they do not fully eliminate the virus when it enters the body, and thus do not entirely stop the spread of the virus from vaccinated people to other people. While the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, and less so the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, do significantly decrease the spread of the virus from vaccinated people, the idea that the vaccines would mostly stop the spread is false. The vaccines were designed to decrease the risk of severe disease and death, not to completely stop the spread of the virus.

Let me repeat that: the vaccines were evaluated to decrease the risk of severe disease and death, and were not initially evaluated or approved based on an ability to stop the spread of the virus (although it was assumed that the vaccines would do that). As Dr. Mina has said, “The only way you’re ever going to stop transmission is if you find people who are about to hit that really high viral load or are already in the middle of it and isolate those people, even for just three or four days until they pass peak infectiousness.”

Then there is the problem of public buy-in. We can be frustrated at the fact that in the U.S., the antiscience, anti-vax, and “health freedom” movements pose serious challenges to public health and vaccination delivery—these problems were already worsening in the years prior to the pandemic. But while pinning the pandemic on the unvaccinated may provide a convenient culprit for our situation, it does not end the pandemic. It also adopts a “personal responsibility” theory of a social problem, emphasizing the choices of individuals as the key factor, rather than “meeting people where they are.” Public health deals with the public as it exists, rather than the idealized public we might wish existed, and if vaccine refusal is common, to the extent it cannot be eliminated, it needs to be worked around. (Besides, some people resist vaccination for reasons that are understandable. A Black couple in Georgia who died of COVID-19 had declined to get vaccinated due to suspicions arising from the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiment. One Trump voter in Arkansas told the Financial Times that he wasn’t getting the vaccine because “If COVID was really serious, we’d have to pay for the vaccine. Everything else is expensive so why are they giving it out for free? It’s suspicious.” In the United States, the concept of “free healthcare” is so unfamiliar as to be highly suspect.)

Meeting people where they are means, among other things, educating them, so that if people are uninformed or misinformed, you can get them to a state of being well informed. This is what President Biden had to say about public health education around vaccination in a May 2021, speech:

“Talk to someone you trust like your physician or your pharmacist or people who have already been vaccinated. Talk to your faith leaders or others in your community that you trust. Look to those people to help answer your questions. […]You know, there’s a lot of misinformation out there. But there’s one fact I want every American to know: People who are not fully vaccinated can still die every day from COVID-19. Look at the folks in your community who have gotten vaccinated and are getting back to living their lives—their full lives. Look at the grandparents united with their grandchildren, the friends getting together again. This is your choice. It’s life and death.”

This plea may seem unobjectionable. But his framing of the problem needs scrutiny. First, not being vaccinated is not the only way to die in this pandemic. What about lack of health insurance, lack of quality medical care, or delayed care (for COVID or non-COVID conditions alike)? What about the people dying whose COVID infections could have been prevented with a simple rapid test or with masking or with use of air filtration and ventilation? The emphasis on “getting back to their lives,” of course, furthers the idea that vaccination obviates the need for other precautionary measures, and suggests that all we need to return to normal is for people to get vaccinated. The entire speech, in fact, only discusses vaccines, as if other public health tools simply don’t exist.

Biden also demonstrates a remarkably hands-off attitude towards public health education. He tells people it’s on them: go and talk to someone. The idea that average people can counter the effects of daily propaganda and conspiracy-theory-mongering by the media or whoever by simply talking to some vaccinated people betrays a fundamental lack of understanding of the serious problem we have around misinformation—and of the government’s responsibility to counter this misinformation with an aggressive public health campaign. Instead of thinking about what will actually change minds, it seems as if the intent here is mainly to shift responsibility. An all-too-common attitude is “if people don’t get vaccinated, the consequences are on them, and the government can’t be blamed.” But if people are ill-informed, that is a failure of the government institutions tasked with educating and informing them.

Biden individualizes the problem, emphasizing the importance of people making the right choices. But good public health policy does not consist of pleading with people to go and talk to other people who will educate them. An effective government gives people what they need, whether that’s masks and rapid tests, free universal healthcare, or paid sick leave.

Vaccines are powerful tools (the author, incidentally, is fully vaccinated), but relying solely on vaccination is clearly not the best approach. We have to ask what will actually work, with the public as it exists, and be willing to consider all answers, not just the answers that fit within a neoliberal framework. We are trying to end the pandemic, not trying to find a way to make sure that it’s people’s own fault if they die of COVID because as individuals they made the wrong choices.

Let’s say we did want to end the pandemic, or at least bring the number of infections down as low as possible. What would we do?

First, let’s think about how the virus spreads. Coronavirus is airborne, which means that tiny droplets called aerosols can infect people even farther than six feet away. Airborne spread happens easily in poorly ventilated spaces, where the concentration of the virus in the air can build up and be inhaled by other people in the space.

Vaccination should be thought of as a last line of defense, not a first. It is last because so many things have to happen before the vaccine has a chance to kick in. There have to be contagious people around you. You have to be around a contagious person long enough and in a particular space for the virus to spread from them to you (apparently not a difficult thing to do with Delta). You have to breathe in the virus aerosols (the most important route of spread) in sufficient quantity—maybe you are wearing a mask, maybe not. The virus has to take up in your body and begin to grow and make copies of itself. Your immune system, having been primed by the vaccine, then kicks in, mounting a defense that, hopefully, causes only a mild illness or none at all.

We need to think, then, about stopping the virus before it gets to the point where we’re counting on the vaccine (or our unvaccinated immune system). We also know that redundancy in preparation is good in life, generally speaking. It’s why you drive with a spare tire and a set of jumper cables in your car. It’s why we all have to prepare for climate-induced power and water outages by buying batteries or generators, spare water, and spare food. For something as dangerous as a pandemic virus, then, you want layers of protection, not just a single layer. This is sometimes called the Swiss cheese model, because it can be thought of like a stack of Swiss cheese slices, with each layer representing an intervention or precaution you might take to prevent catching the virus or getting sick. Each intervention has its own weakness (a hole), as no intervention is 100 percent effective. If you stack multiple interventions on top of each other, their holes are unlikely to line up, and you end up with a solid barrier of protection between you and the virus. However, with only one layer, you are left with a gaping metaphorical hole between you and the virus.

What are the other layers beyond vaccination? We do have tools at our disposal that take effect before a person even becomes infected with the virus. Masks are the most obvious. A mask blocks respiratory particles the moment you put it on. But mask policies vary wildly around the country. We should have implemented Bernie Sanders’ Masks for All legislation long ago (the legislation went nowhere) and implemented a federal mask mandate. (“Federalism,” the resistance to any kind of nationwide policy, often makes little sense in normal times, much less during a nationwide pandemic, especially when people can travel more or less freely between states. The situations that call for a strong federal government, rather than 50 states acting on their own, are those that implicate the entire country.)

Then there’s rapid testing. A rapid antigen test can tell you whether you are contagious with COVID-19 in as little as 15 minutes’ time. These tests are as simple to use—and utilize the same technology—as home pregnancy tests. Frequent use of rapid testing is better, for public health purposes, than PCR (which, in the U.S., has taken anywhere from hours to days to longer to return a result, and can turn up positive even before or after a person is contagious). Studies by U.S. colleges have shown success with rapid testing programs. Studies of rapid testing in public transit and in other countries have shown success as well. As a February 19, 2021, article in The Lancet notes, “In the midst of a raging plague, it is inequitable and unethical not to deploy high quality rapid tests alongside existing public health interventions.” In December 2020, over 50 experts wrote an open letter encouraging the federal government to use the Defense Production Act to ramp up test production. The cost of testing is minuscule compared to the cost wrought by the ongoing pandemic. Yet the Biden administration only just announced that it would commit substantial funding to increasing rapid testing availability, and at the moment few tests remain on the market, even fewer are in stock, and the prices are prohibitive for frequent use. Last year’s compelling case for Daily Quick Tests explains how easily testing can be carried out. What we really need is a Testing for All plan, similar to Sanders’ Masks for All, to make free, universal testing available to all and to give special assistance to unvaccinated people and those who are otherwise marginalized (institutionalized people, the unhoused, disabled or medically fragile people) and who are at higher risk of COVID-19. Aggressive testing means shorter isolation times since testing can pinpoint when people are contagious.

If you want to stop the spread of a virus that is carried via aerosols, it’s also important to think about air filtration and ventilation. A HEPA filter can remove virus particles from the air. Ventilation, which means bringing in fresh air, can also help dilute virus particles in the air, making the air safer to breathe. We need to take a serious look at building filtration and ventilation. I’m not saying this is a quick thing, but we’re not even trying at this point—inexcusable, as this pandemic drags on. (Here is an informative thread by epidemiologist Eric Feigl-Ding about air filtration, and here is an informative article about how to make indoor air healthier to breathe.)

Beyond that, the U.S. needs to get serious about guaranteeing people adequate basic healthcare, so that they do not have preventable health problems. Every illness that goes untreated because people cannot afford treatment is not only an unnecessary harm, but also needlessly makes people more vulnerable to COVID (and in future pandemics). We have a simple and effective way to ensure that a lack of money isn’t making our population sicker. Medicare For All (M4A) would give comprehensive medical care (including vision, dental, hearing, and mental healthcare) to everyone living in the U.S. and end all the premiums, copays, deductibles, coinsurances, and surprise bills that make getting healthcare a nightmare. M4A would end the ridiculous scam that is the Affordable Care Act marketplace exchange as well as the unjust for-profit commercial health insurance system we have now. Ultimately, the United States faces a simple question: is it going to do what is necessary to keep its population in good health, or is it going to let people die needlessly? We know what the answer has been so far.

What are the different “endgames” for the pandemic? In a March 2020 piece in the Atlantic, Ed Yong predicted three scenarios for “How the Pandemic Will End.” The possibilities were: all countries bring the virus under control in a coordinated manner (unlikely, he wrote); the virus “burns” though the world population and eventually fizzles out due to “herd immunity”; or we play a “protracted game of whack-a-mole” with the virus, putting out flare-ups while waiting for a vaccine to be developed. Yong recently wrote that, unfortunately, for the U.S., the virus is “here to stay,” meaning it will become endemic. The hope is that eventually (once enough people have been exposed to the virus through vaccination or infection), the virus will become more like a common cold virus, or maybe occur seasonally similar to the flu; however, this remains to be seen. (It should be noted that the flu typically kills tens of thousands of Americans each year, so the flu is not benign like a common cold.)

Some countries or regions that have aggressively responded to outbreaks have been able achieve very low levels of virus. The degree to which a given country has managed to control the virus clearly depends on the choices that countries (and global superpowers) make around public health mitigation measures and vaccination, as well as the presence of variants.

Now we have a changing narrative around what is considered possible, as Yong writes in his recent piece. What was considered possible, and desirable, was herd immunity through vaccination. Even in the early days of the pandemic, according to a May 3, 2021, New York Times article, “when vaccines for the coronavirus were still just a glimmer on the horizon, the term ‘herd immunity’ came to signify the endgame: the point when enough Americans would be protected from the virus so we could be rid of the pathogen and reclaim our lives.”

“Herd immunity” is a concept, a theoretical framework for explaining how vaccination (or natural infection) works to decrease the spread of disease. But it wasn’t inevitable. And there are three factors that make herd immunity through vaccination increasingly unattainable. The first is stalled progress on vaccination levels. The second is the emergence of the Delta variant, which spreads more easily than the original strain of the virus, thus requiring a higher herd immunity threshold (previously estimated to be around 60–70 percent, now estimated to be around 80–90 percent). The third is the fact that vaccination does not halt spread of the virus—at least not anywhere near to the degree that the CDC thought it would (thus prompting the CDC to reverse its May 2021 mask rollback guidance for vaccinated people).

This brings us to another important consideration: the Delta variant. In his recent, previously cited, article, Yong declared, “Delta has Changed the Pandemic Endgame.” But this kind of declaration is heavy-handed and dangerously misleading. There are factors about Delta that make it harder to deal with, now that it’s here. But this is not the primary issue. We cannot confuse the unfortunate facts around Delta’s spread with the facts of our policy decisions that led to the rise of Delta.

Just as herd immunity was not inevitable, the emergence of Delta was not inevitable. Delta rose to prominence in the global south (India), where relatively few people had been immunized. Then it spread to the UK, U.S., and all over. Around the same time Delta was causing a rising wave in the UK in the summer, the CDC rolled back its masking guidelines, told vaccinated people not to get tested, and delayed recognition of Delta as a ‘variant of concern’ until mid-June, a month after the WHO declared Delta a concern.

No, Delta was not inevitable. Delta was a choice. To quote Yasmin Nair in “Stop Blaming the Unvaccinated”:

“None of this is unexpected and could have been easily averted if Biden had instituted a nationwide mask mandate and made sure that at least 75 percent of the country was vaccinated before telling people they could take off their masks. Instead, after caving in to a typically American desire to be delusional and selfish about ‘normalcy,’ here we are with the frightening prospect of sliding back to square one. Biden, who has still to take action on anything like healthcare for all now calls this a ‘pandemic of the unvaccinated.’”

The point here isn’t whether the 75 percent threshold is exactly right, or that masking is the only thing we should have been doing, but that Biden and the CDC acted prematurely in rolling back masking this past summer. Our policies, from the beginning, set us up to fail at eradicating the virus. This was a choice in the extreme. On the other end of the spectrum, “zero-COVID” countries such as New Zealand, Australia, China, Singapore, and Taiwan opted to use more aggressive measures including closing their borders and locking down their populations. Countries that pursued COVID “elimination… had lower per capita death rates, shorter and less strict lockdowns, and faster economic recoveries than the mitigation camp,” though recent news indicates that these countries are now partly “learning to live with the virus.” Norway and Denmark, two countries that “beat” the virus, are lifting restrictions. The path the United States has taken has clearly not been inevitable.

Our vaccine-centric policy set us up for a vision of an endgame that was severely constricted. But we need to move on. If individuals have “choices,” so do nations. Even if the virus is likely to become endemic, or remain circulating in the population (remember, there will always be new people who are relatively naïve to the virus coming into the population, including newborns, visitors from isolated communities, people who have recently become immunocompromised, and so forth), it does not mean we have no responsibility or reason to use all the public health tools at our disposal now to reduce infections to the lowest number possible starting today. We should aim for zero new infections and to respond aggressively to outbreaks when and where they occur. The point is not, we must get to zero cases or we have failed, but to behave as if we wanted to get there. The other nations are only lifting restrictions because they have been doing them for over a year. We don’t get to give up on strategies that we haven’t tried.

The media has now declared defeat. In the same recent Times article, the title read: “Reaching ‘herd immunity’ is Unlikely in the U.S., Experts Now Believe.” (You can find the same headlines all over the internet.) Yong admits that herd immunity is “mathematically impossible” with our current vaccines.

But those who have resigned themselves to the endless continuation of the pandemic are among those least likely to be victims of it. If we care about the lives of the vulnerable, marginalized, and sick, then the question is not “will the pandemic end?” but “what must be done to end the pandemic?” Remember that the responses and rhetoric of those in power to the pandemic are symptoms of a society and polity governed by neoliberal ideas of individuality and personal responsibility in the free market. Serious efforts to end the pandemic are not made because demagogues spread misinformation and lies, there is bipartisan indifference to the suffering of ordinary people, reactionaries fight aggressively against basic public health interventions like masking, and the ruling class is doing just fine in all of this, continuing to make massive profits.

We do not need to accept the status quo as inevitable. The policy choices that have prolonged the pandemic are an assault on basic freedom; people cannot live their lives freely when under the threat of a dangerous virus. We should all still desire an outcome that reduces the spread of the virus as much as possible, rather than reconciling ourselves to it. We should want this because it will reduce human suffering and death, in both the short term and the long term, and as human beings it’s our responsibility to care for one another. When asked whether we should “still aim for zero [cases]”, Dr. Feigl-Ding said in a recent interview with World Socialist Web Site:

“I would phrase it this way. I don’t think we should wave the white flag saying, ‘Oh, we are at endemic levels. Let’s give up. You have to learn to live with the virus.’ The learn to live with the virus mantra is last year’s natural infection herd immunity. And now it is learning to live with the virus. And I don’t think we should go there right now. I don’t think we should go there at all, especially when kids are not vaccinated yet. We should aim for zero; we should aim for as low as humanly possible, like add on every mitigation we can practically do to get cases low, to avoid hospitalizations and deaths, and avoid Long COVID and Long COVID in children. I think that is just so critical.” (emphasis mine)

Dr. Feigl-Ding goes on to point out that it is morally unacceptable for us as a society to allow, say, childhood deaths from cancer or gun violence, or nervous system damage due to childhood lead poisoning. So why would we accept COVID deaths and long-term health effects for children? But it shouldn’t be just children we worry about. Nobody of any age deserves to suffer from the harms of COVID, and we should not accept this state of affairs for any person in society.

Doing more to stop the virus’s spread would make all our lives better. The less virus that circulates among the public, the safer public places will be. We need a massive public health campaign to educate the populace. This would take advantage of the already-massive advertising capabilities we have at our disposal—Internet, TV, websites, billboards, radio, podcasts, magazines, etc. If, as a capitalist society, we can manufacture demand for commodities, and we can force people to watch on YouTube, for example, an ad for car insurance or some new tech gadget they don’t need, we can certainly put up ads about coronavirus—around masking, testing, vaccination, filtration, and so forth. Because institutional trust is so low, we’d need to have trusted local leaders (religious and civic leaders, elected officials, other community leaders and organizers) play a role in making and delivering these messages. Right now, where is the messaging strategy?

Beyond that, we need a commitment from the U.S.—and the wider global north—to end the pandemic, to get infections down to the lowest levels possible, and to maintain flexible public health strategies that can be deployed when and where they are needed. Public health education, masking, and rapid testing may be less sexy—and less profitable for Big Pharma—than expensive new pharmaceutical products (vaccines). But low-tech, simple solutions are the backbone of the public health toolkit for stopping new coronavirus infections. This is about substance, not style (or profit).

Here’s another way to think about it: we have cheap, fast, and easy-to-use public health tools that, alongside vaccination, can help us stop the spread of the virus, helping us end the pandemic so that it doesn’t linger indefinitely. Instead, what we have prioritized are expensive, fragile, and unevenly and unfairly distributed pharmaceutical products that significant portions of the U.S. population (and world) haven’t taken. I often think of something prison abolitionist Angela Davis has said about her experience growing up under segregation and racial violence. “My mother always said to us: ‘This is not the way things are supposed to be, this is not the way the world is supposed to be.’”

Well, the way things are with the pandemic is not the way they are supposed to be. It’s not normal. We shouldn’t accept it.

Understanding the way our leaders have mishandled the pandemic can be depressing. It can also be empowering. We know that the solution is not to hunker down, hate one’s unvaccinated neighbor or family member, and carry on. The solution is to organize, find solidarity with others, and believe in a world in which education and public health can empower people to make better decisions and give us the tools we need to protect ourselves. We need to believe in a world in which ordinary people can push those in power to do what needs to be done to end this pandemic. We need to believe in an ending different from the one that those in power want us to see—which is just more of the same: more sickness, more suffering, more death.

If we haven’t been trying to end the pandemic, now would be a great time to start.

Note: Brief update March 11, 2022. A new variant, Omicron, has emerged since this piece was published, and the CDC has recently issued a “community level” set of guidelines that essentially rolls back masking in much of the country despite the fact that at least a thousand people have been dying each day of the virus and cases of Long-COVID continue to rise. The main argument of this piece remains highly relevant: we have the tools and knowledge to reduce cases but we continue to refuse to do so.