Sidewalk Socialists and the Path to Power

A number of impressive socialist candidates are running in Somerville, MA—and their nitty-gritty approach to municipal power may have broader implications for the left project as a whole.

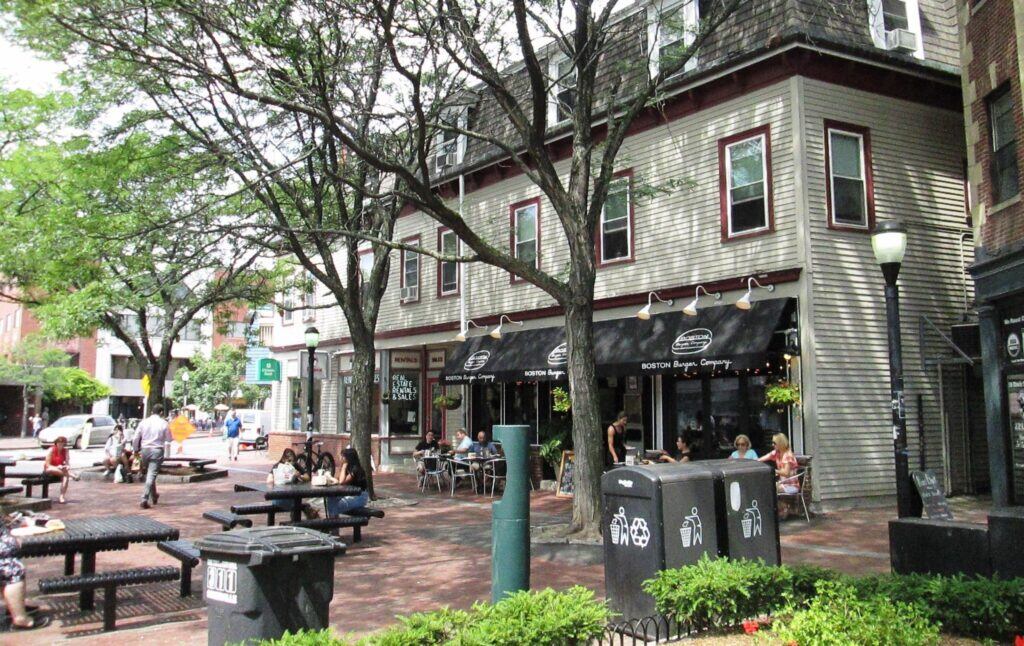

On a warm afternoon in late May, Charlotte Kelly spoke to a half-dozen volunteers ready to knock doors for her City Council of Somerville campaign. A densely-packed city of 80,000 nestled within Boston’s patchwork suburbia, bounded to the south by Cambridge (of Harvard and MIT) and to the north by Medford (of Tufts), Somerville has found itself host to an intense summer-long political battle for municipal government. With months to go before this relatively minor primary (in September), Kelly’s campaign already runs canvasses almost daily, and Tuesday isn’t even the busiest weekday, she told me.

When a short orientation wandered into a discussion of bike lanes, Kelly herself cut in: “This neighborhood in particular, Washington Street, got two bike lanes added, and Beacon Street has bike lanes added, and so some residents lost parking. For me, I talk about comprehensive road safety, for bikers, walkers, drivers, etc.” As Kelly continued, volunteers nodded. “And how we can’t build bike lanes in a piecemeal fashion, which means that a biker or a driver goes from one situation to another very quickly and they don’t know what’s going on. So talk about things like holistic changes to the road, making sure that we are building universal systems for biking and transit traffic.”

Kelly is one of seven candidates running for Somerville City Council who has been endorsed by the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). This slate of campaigns is bound not just by the idea of winning socialism in a general sense, but specific, concrete reforms to pave the way. To get there, the candidates demonstrate intricate knowledge of policy battles and embed themselves in community organizing, but it’s more than that, too: their proposals for the future drill down to the details. According to Spencer Brown, co-chair of Boston DSA, the election centers on three issues of daily life—affordable housing, climate change, and public safety—and in addressing those issues the DSA-endorsed candidates move seamlessly from broad-stroke abstractions to net zero stretch code and idling police cruisers. The slate in Somerville has the potential to translate the grand aim of socialism into the minutiae of city politics.

Besides the mayor, Somerville’s municipal government includes an 11-seat city council, with four at-large and seven district seats. Two of the incumbent district councilors are also endorsed DSA members: J. T. Scott in Ward 2 and Ben Ewen-Campen in Ward 3. Beyond the incumbents, the socialist slate features five candidates running in open races, including three for the four at-large seats—Charlotte Kelly, Eve Seitchik, and Willie Burnley Jr.—and two more for district seats—Tessa Bridge for Ward 5 and Becca Miller for Ward 7. According to a spreadsheet by Calla Walsh, data from the Massachusetts Office of Campaign and Political Finance shows that, as of the end of June, all seven DSA district candidates lead their races in fundraising (though Miller leads what may be the tightest district race by less than $2,000).

But it’s important to consider the slate collectively, Boston DSA co-chair Brown said. For some, the decision to run itself was collective and contingent on others’ running, but also prompted by the disappointments of the current Council’s governance. On paper, the Council looks like a fairly left-leaning legislative body. Besides the two socialist incumbents, a clear majority identify as “progressive.” Back in 2017, coming off of Bernie’s first run, Our Revolution secured a wave of victories in the city. But amid the uprising against police brutality sparked by the state murder of George Floyd, the Council failed to implement a full 10 percent cut to police spending, a decision some candidates cite as something a socialist-majority Council would have done differently.

When over a thousand people gathered in Boston to counter-protest a white supremacist “Straight Pride Parade” in August 2019, they were violently attacked by Boston-area police, including Somerville PD. Seitchik, one of the at-large candidates—and a data scientist by trade—was there with trans and queer protestors alongside straight and cis allies, and “saw people in Somerville police jackets tackle and arbitrarily arrest my friends… You know when I walk past the Somerville police officer[s], I see them tackling my trans comrades.” This encounter helped lead Seitchik to consider policy goals that can reimagine the role of the police entirely; as they continued: “There’s no reason … why we couldn’t have civilian traffic enforcement, why we couldn’t have civilian dispatcher or station officers, why we couldn’t have nonviolent mental health response.”

Besides policing, housing presents a particularly intractable problem in metro Boston because while city councils control many aspects of development, one larger fix—rent control—is currently banned state-wide. But instead of simply expressing support for rent control within the city, at-large candidate Willie Burnley Jr. proposes geographically wider coalitions: “I’m willing to fight for [rent control] in a different way, and not to rely on the structures that currently exist vis-à-vis the Statehouse but to actually bring that to the people. I’m willing as an organizer to go out of my way, beyond just the boundaries of Somerville, to build regional support … that is broad enough and has a strong enough coalition that can actually pass rent control.”

Seitchik makes a parallel argument: “One thing that’s cool as a socialist about being a city councilor is you have this platform where parts of society that aren’t always listening to our message—or don’t always get our message from the mainstream press—suddenly are getting our message, because [as a city councilor] you know you can say things and… papers will print them right.” In other words, despite the fact that Somerville alone can’t make some of the larger reforms, a majority of local elected officials forcefully pushing for that measure could help foster a larger public movement to finally remove the nearly 30-year ban on rent control.

This upcoming election in Somerville also may have wider implications, both in the Boston area and nationally. All over the country, not just in big coastal cities but in places like Florida and Texas, socialists are running for municipal office. But even in the largest DSA chapter in the country—New York City—DSA put up six candidates in the June primary, contesting only 12 percent of the City Council (and only winning two races). Meanwhile in Chicago and Seattle, socialists make up about 10 percent of their respective city councils. But in Somerville, 64 percent of seats are being contested. The prospect of winning an outright majority represents, in the words of Seitchik, “a generational opportunity, the first time since World War II, the first time in 80 years, to be able to have a majority socialist City Council.”

In fact, as DSA’s national account recently corrected, the city of Richmond, California already has a majority-socialist City Council—an indication that what’s happening in Somerville is not as anomalous or isolated as it might at first seem. In 2020, East Bay DSA (among other groups) endorsed a slate of three Richmond candidates who were then successfully elected, joining sitting DSA member-candidate Eduardo Martinez and constituting an outright majority of the seven-member body. As an approximately 100,000-person edge-city of a major metropolitan area (San Francisco), Richmond resembles Somerville in certain ways, and its recent history battling Chevron, passing a rent control ballot measure, and various other socialist-minded initiatives lays out a potential blueprint for Somerville’s near future if this DSA slate wins.

Unlike Richmond’s 2020 elections, where several DSA candidates previously served in municipal office, five of the seven 2021 Somerville candidates are running for the first time, and the entire council is up for election. But despite the city’s higher turnover and relatively untested candidates, a historic victory—at least according to the leadership of Boston DSA—is within reach. This possibility leads to a cluster of pressing questions: first, what does it look like to run seven socialist campaigns simultaneously in a city of only around 80,000? Then, how could this kind of power suddenly acquired at such a local level be successfully harnessed? What are the connections between filling potholes and ending capitalism?

Seitchik looks to the socialist-dominated municipalities of an earlier era, specifically the sewer socialists, who won a majority on the Milwaukee city government in 1910. As Dan Kaufman writes in the New York Times, these municipal socialists pursued a “blend of unwavering idealism and dogged gradualism”:

They installed hundreds of drinking fountains, prosecuted restaurateurs for serving tainted food, and compelled factory owners to put in heating systems and toilets. Most significantly, Seidel appointed an aggressive new health commissioner, whose department oversaw a reduction of more than 40 percent in the number of cases of the six leading contagious diseases, among them scarlet fever, whooping cough, and smallpox, within two years.

In a longer academic study of these early-20th-century Midwestern socialists, Douglas E. Booth concluded that socialist control, contrary to conservative talking points, led to improvements in the “efficiency and quality of municipal service delivery.” Socialist ideology itself inspired improvements in city functioning. For example, as Booth’s study highlights, Milwaukee began “operating its own asphalt repair plant and portable stone crusher,” a change “symbolic of the savings possible by carrying out production directly rather than purchasing materials from private vendors.”

Many of Milwaukee’s elected socialists were defeated in 1912, including then-mayor Emil Seidel. But socialist Daniel Hoan kept his seat as city attorney in 1912, and in 1916 was elected mayor, serving for decades until 1940. The last Milwaukee socialist to win the mayor’s office was Frank Zeidler, who was elected in 1948 and somehow managed to hold on to re-election two more times during the McCarthy era.

For Seitchik, the relative longevity of Milwaukee and other historical municipal socialists—even in the face of an extremely hostile, anti-left era—shows why the label matters. “Socialist” may have been a bad word during the Red Scare and the McCarthy era, but the sewer socialists had a reputation, supported by the success of their reforms, of being ideologically incorruptible. William Evjue, a Republican assemblyman in 1917, claimed that “[The sewer socialists] never were approached by the lobbyists, because the lobbyists knew it was not possible to influence these men.”

Seitchik says the same about the Somerville slate. “We’re people who are ideologically not careerists, are not here to build relationships with the wealthy and powerful,” they said. “We’re here to organize regular people.”

To describe Somerville’s slate, Seitchik proposes the term “sidewalk socialists.” The image calls to mind Kelly’s bike lane taking points, where policy quite literally impacts how people are moving through the world. And “sidewalk socialists” carries a specific connotation for this densely populated Northeastern suburb: snow. Not plowing sidewalks, Seitchik argues, creates a public health cost. Shoveling can be harmful to seniors, and unplowed areas restrict access not wide enough for wheelchairs. Seitchik proposes: “If we had municipal sidewalk plows, that would create good union jobs, but it would also make the city a more livable place for the people who live here.”

As a phrase, “sidewalk socialist” also has a historical meaning, but as something closer to an insult. The early Catholic socialist Thomas Hagerty used the term to describe those more focused on parliamentary fixes rather than full-on revolution. Seitchik agrees that “we can’t reform and legislate our way to socialism,” but sees the two methods as related, rather than mutually exclusive.

For Seitchik, the project of movement-building, municipal policy, and long-term socialist goals are all intertwined. “How else can we build a movement powerful enough to change the world unless we meet people where they’re at with the issues that affect their day to day lives.” If the goal, Seitchick believes, is “to show people the strength of socialist ideas in practice, the sidewalks are just the beginning.”

The road to seven viable candidates for eleven seats in a relatively small city involved a combination of years of intentional work by Boston DSA, plus a fortuitous set of circumstances. Running members of DSA as candidates meant that each one had already identified as a socialist before announcing their campaigns, though for each, coming into a socialist identity meant different things.

Willie Burnley Jr., a Black activist and former campaign staffer, said that he didn’t “come from a particularly political household.” His parents, he said, are “pretty apolitical and pretty mainstream Democrats. They care about politics maybe once every four years. They don’t have any particularly strong policy views on anything. And they were both born in the South… my dad was born in the 50s in the South, he comes from a pretty socially conservative viewpoint.” Burnley describes getting involved in mass movements, particularly Black Lives Matter, as helping him see “that capitalism just fundamentally was not going to provide me or the people I grew up with our basic needs.” Even so, “it took me a long time to get to” socialism.

“And it took me a long time to get to that point quite frankly, partially because I saw a lot of white socialists doing things that I thought were inappropriate at protests or appropriating conversations in ways that felt disingenuous to me, particularly around racial justice and in the wake of police murders,” Burnley said. “So I kind of struggled with it for a couple years but… then I made the switch. I had thought of myself as an anti-capitalist of some sort, but realized, no I’m just a socialist because socialism gives me a framework, by which I can at least argue that all these things should be basic human rights.”

In addition to each candidate’s personal conversion, Boston DSA recently transformed its political strategy. Spencer Brown, the aforementioned Boston DSA co-chair, explained that instead of simply endorsing campaigns that were already up-and-running, the chapter followed New York City DSA in developing their own candidates.

Specifically, Brown continued: “we want to be running the canvasses, we want to be really internally mobilizing our members, and making them feel like this is a Boston DSA event.” Brown envisions DSA “fulfilling a role that there isn’t really in the American electoral system, and especially post the kind of political machines of the past.” He identifies a broader shift in socialist thinking—from challenging machines to building them, an idea which was stated directly in a recent essay by Patrick Dalton of DSA’s Metro D.C. chapter. “The left,” writes Dalton, “needs to build our own political machines.” Both DSA members advocate for a shift from candidate-centered electoral work to an apparatus built on cross-endorsed slates. It’s the difference between an electoral strategy of individual insurgent candidacies versus what Dalton calls a “governing majority.”

From backyards to doorsteps, these sidewalk socialists are working towards winning elections, and in the course of the campaign presenting a vision of the future they could help build. On what that would take, Seitchik puts it simply: “Field wins left elections.” With still many weeks left until the primary, the DSA slate has not yet seen a fully coordinated response to their campaigns, but pushback is likely to materialize. When socialists win power, capital responds, from Amazon’s 2019 efforts to unseat Kshama Sawant in Seattle to Chevron’s $3.1 million poured into Richmond’s municipal elections. Boston DSA’s main, and perhaps only, advantage derives from the time and energy of its members. As Seitchik says: “We don’t have a mass media,” nor wealthy donors, “Ultimately, our strategy is to go out into our communities and talk to people about this vision.”

In some sense, the organizing produced by the election is the key goal of the entire project, even more so than the elections themselves. As much as they are running to implement specific policies, Seitchik argues, they are also running towards the “dream” of “an organized city where regular people participate in politics en masse.” An organizer-voter model would mean more accessible city meetings, and Seitchik suggests changes like “free childcare in meetings,” and “live translation into Spanish, Portuguese, and Haitian Creole.”

Besides specific policy measures that could make city governance more accessible, Kelly discusses the change from candidate-centric to movement-centric politics as a “narrative shift.” As Kelly says, the project represents “not just this individualistic mindset that politics often moves you towards, that you have this personality to get behind, and you’re really excited about this one person.” Instead, “it’s about the people that we’re trying to bring into the process.”

Ultimately, this can only happen through scheduling many dozens of volunteers to knock on thousands of doors throughout the coming summer, which, even considering the density of membership in the city, represents a significant amount of work. But Seitchik says that for members, having friends from DSA as the candidates themselves functions as a motivating force. Ideally, the process not only activates membership but brings in socialists-to-be. Because while the canvassers often don’t lead with their socialist credentials, they often end up spreading socialism by proxy. As Kelly says, when it comes to door-knocking, “not everybody is a socialist, and not everybody who is a socialist realizes they’re a socialist.”

If these candidates do succeed and win a majority, what could they achieve? Could the ideas cultivated in Somerville actually extend outside its boundaries? Or is Somerville just an exceptionally fertile place for socialism, with a high percentage of renters and an already-progressive local government, beyond which this energy and these policies can’t spread?

Certainly, Somerville is unique. As Burnley puts it, “We got four square miles. If there’s any place that has the gumption and, not structural ability, because we have a Statehouse that is tying one hand behind our back, but we have a community that’s small enough that we can actually talk to everybody, and we can actually get people on board to try to implement these big ideas on the local level.”

To demonstrate how policy can spread from town to town, several candidates cite policies that nearby cities have introduced, such as Lawrence’s free buses, the “Chelsea Eats” program, or Cambridge’s basic income. (The examples also show, Kelly points out, how “Somerville loves to talk about how progressive it is, and then our neighbors show us up on a lot of the things that impact people’s material conditions.”)

The ideas proposed by and fought for by Somerville City Council members could leave these four miles; as Burnley points out, certain ideas proposed by the two incumbent socialists on the Council, like recognizing polyamorous partnerships and banning prison labor, already have. In that same way, additional proposals, such as a free transit pass, could serve as inspiration to other communities, as Brown suggests. “If you get a city to create a program that can do that, if you just have the bravery to do that in one place,” he says, “that program can spread and you can create a whole new model of public goods for all people in Massachusetts city by city.”

Here in Somerville, the candidates are all running not only because they want to propose interesting ideas that could spread beyond the city’s borders, but primarily because, as Kelly puts it, they want to “wield real power.” They want to change the material conditions of their city and build an organized electorate. The extent to which a majority-socialist Council succeeds will be determined not only by the headline-catching proposals they implement, but also, in the spirit of the sewer socialists before them, by whether they fix the bike lanes and plow the sidewalks.