What Is The Value of “Intellectual Diversity”?

Multiple points of view are valuable in many domains, but consensus is often critical.

In 1997, one of the oddest sites on the internet appeared: TimeCube. Created by the supposed “wisest man on earth,” Otis Eugene “Gene” Ray, it posited a “theory of everything” that claimed to have debunked all world religions and sciences. A representative excerpt from TimeCube:

Until you can tear and burn the marshmallow to escape the EVIL ONE, it will be impossible for your educated brilliant brain to know that 4 different corner harmonic 24 hour Days rotate simultaneously within a single 4 quadrant rotation of a squared equator and cubed Earth. The Solar system, the Universe, the Earth and all humans are composed of + 0 – antipodes, and equal to nothing if added as a ONE or Entity. All Creation occurs between Opposites. Academic ONEism destroys +0- brain. If you would acknowledge simple existing math proof that 4 harmonic corner days rotate simultaneously around squared equator and cubed Earth, proving 4 Days, Not 1Day,1Self,1Earth or 1God that exists only as anti-side. This page you see – cannot exist without its anti-side existence, as +0- antipodes. Add +0- as One = nothing.

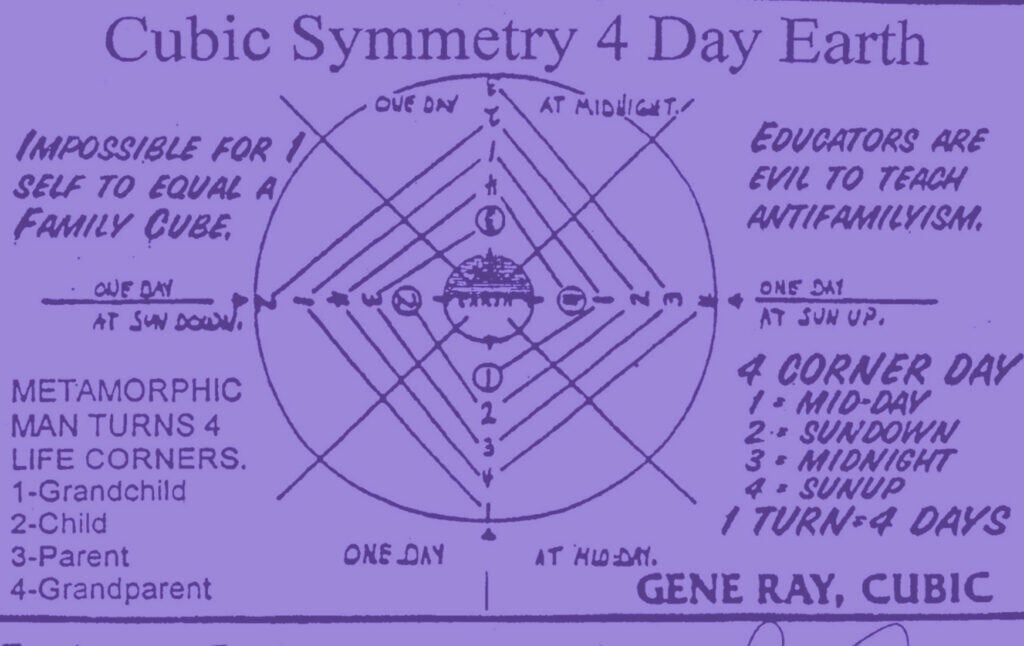

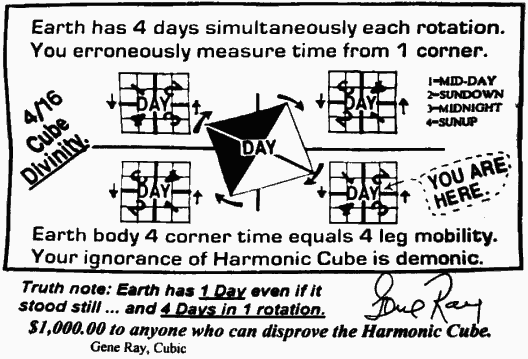

Don’t worry if you can’t understand, it takes some time to grasp the wisdom of TimeCube. This chart might clear things up:

Now, personally, I like that TimeCube exists, because harmless eccentrics make life on earth more interesting. But Gene Ray having a web page is different from Gene Ray having, say, a tenured position in the CalTech physics department. Giving him tenure at CalTech would certainly make the faculty more intellectually diverse. Probably it would make faculty meetings more interesting. But the fact that an opinion is different doesn’t make it inherently intellectually valuable. (Gene Ray did once get to give a lecture at MIT, because students thought it would be amusing.)

On some subjects, academics have achieved consensus. If you reject the Second Law of Thermodynamics, you’re probably not going to make it as a physicist. If you think the Holocaust never occurred, you are (hopefully) not going to have a place in a university history department. Yet one alternate way we could describe this is to say that by demanding academics conform to the consensus, universities are enforcing uniformity of opinion and refusing to tolerate dissent. But we could say that of any attempt to apply a standard of intellectual rigor. The existence of “standards” could be taken as a refusal to tolerate differences of opinion, an authoritarian insistence that some knowledge is “correct” and other perspectives should be ignored. (I should have used this as an excuse when I failed math quizzes in middle school.)

Conservatives sometimes complain that academia does not have sufficient “intellectual diversity,” by which they tend to mean that university professors are overwhelmingly liberal. State legislators have even introduced “intellectual diversity acts” that would require colleges to bring more conservative speakers to campus so that “both sides” of an issue can be heard. Florida Republicans have passed a measure that “would require public colleges and universities to survey students, faculty and staff about their beliefs and viewpoints” to test whether campuses are sufficiently intellectually diverse. George Mason University’s Institute for Humane Studies says that “if liberal arts colleges are becoming less and less intellectually diverse, that presents a serious problem.”

But does it? When “intellectual diversity” is described in the abstract, it seems like something desirable. Usually it is framed as “believing students should hear many points of view.” But as the examples of the TimeCube and Holocaust denial should tell us, it’s hard to actually have these conversations in the abstract. Should students be taught multiple points of view on whether phlogistons are real? They don’t tend to hear multiple points of view on that question, because one point of view is substantially more grounded in real-world evidence than the other. And it’s all right that the history department doesn’t let half of all World War II lectures be conducted by Nazi sympathizers for the sake of “balance.” Balance isn’t necessary or desirable on questions where an outmoded theory has been disproved by hard evidence, and “hearing both sides” on literally every question can lead to a kind of radical relativism where academics abandon their task of finding, preserving, and teaching the truth.

It’s understandable why those on the right think the universities are not sufficiently “intellectually diverse.” If you are a conservative, and you look at academia, you will see a place where your beliefs are largely rejected. There are a couple of ways you could interpret this: (1) you could think that as people become more educated, and study the world more, they shed conservative beliefs, because conservative beliefs are outdated, being less well-founded in reason and contemporary evidence (2) you could think that universities are brainwashing factories that reproduce a leftist ideology and need to be stormed and taken over. Obviously, (1) is unacceptable to the right, because it would involve admitting that right-wing beliefs are more difficult to hold onto when you learn about the world, so conservatives tend to go with (2) and present the university system as an indoctrination factory that forcibly excludes perfectly sensible and rational right-wing beliefs from being heard.

To this end, the right believes it is justified in trying to adjust the balance between right-wing ideas and left-wing ideas in the academy, even if this means using outside money or legislation to do it. Conservative groups have, according to the New York Times, “funded new professorships in topics like ‘the history of capitalism’ and poured money into speaker series and academic programs that propagate libertarian policy ideas.” (I am all for teaching the history of capitalism but I suspect there is a bit more Rand than Marx on the syllabus.) In Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right, investigative journalist Jane Mayer documents the alarmingly widespread effort by right-wing groups to establish professorships that push free-market ideology, including at public universities. But they insist that this is just an effort to ensure that Diverse Perspectives are represented, and that “propaganda” of left-wing college professors is countered.

Rejecting the “intellectual diversity” concept can sound elitist or exclusionary. But many conservative ideas have struggled in the academy in part because they do not always pass important tests of intellectual rigor. For example, when the Third World Quarterly pulled a paper defending colonialism, it was portrayed by the right as a politically correct refusal to hear alternative points of view. In fact, the paper was as shoddy as something written by a Holocaust denier. It was poor scholarship. The stuff that gets churned out of right-wing think tanks is often pseudoscientific rubbish. Conservatives often seek to portray this as censorship or a failure to hear them out, because they do not see themselves as pseudointellectuals, but if an argument in favor of colonialism is as factually shoddy as a Holocaust denier’s pamphlet, then it is justified on the grounds of scholarly rigor to retract it from a journal. The call for academia to be more open to “diverse political perspectives” sounds compelling, but we should understand that it may involve treating “things that are false” as a “perspective.” This is the very kind of radical epistemological relativism that conservatives so frequently decry, the belief that because there are multiple views on a topic, all views should be treated as equally legitimate for the sake of diversity. All of a sudden, conservatives have gone postmodern. Their beliefs should be taken seriously because they are beliefs, without having to be subjected to any objective test of accuracy.

Now, I do think there’s a serious problem when people undergo a university education and don’t hear conservative arguments or understand how they work. I actually think studying Holocaust denial literature can be an important part of studying history, because it is important to see how fabricators function. I think Ayn Rand’s works should be assigned. I took a sociology class that assigned passages of The Bell Curve so that the professor could show how the statistical distortions and faulty extrapolations occurred, and this was very valuable. I don’t think it’s necessary or healthy to pretend the conservative point of view doesn’t exist. Nor do I believe in censoring alternate views; it is always possible that an unusual or heterodox view, particularly in the sciences, may someday become the new consensus. I am, as a general rule, a believer in the principle that student groups should be able to invite any speakers they like to campus. And I also think that scholarship that distorts the truth in order to push left ideas is a betrayal of the core principles of academic inquiry. Everyone’s work needs to be subjected to scrutiny and no consensus should survive merely because it is the consensus. I have read some real dreck during my time in universities.

But this does not mean that academia should itself be drawn from “intellectually diverse” perspectives solely for the sake of contrarianism. The solution to the existence of some biased dreck is not more diverse biased dreck. As an abstract matter, there is no automatic value to having multiple points of view on a subject. A medical school comprised half of those who do believe in the germ theory of disease and those who do not is technically more diverse, but it is also likely to kill more people. It can be valuable to have lots of points of view, but it depends on what the subject is and what the views are. Back to our friend the phlogiston: many scientific theories run their course, and lead to better theories. It may be necessary to teach phlogistons as part of the history of science, but phlogistons are not a useful point of view to teach alongside generally accepted particle physics. Particle physics itself will also flow and change, and new theories may at first be regarded with skepticism. But again, that does not mean universities should teach TimeCube in a serious manner. Consensus helps us weed out quackery.

Of course, an academic discipline where everyone held the exact same beliefs would be intellectually barren. (There are no such disciplines.) And there are plenty of areas of gray where debate flourish. But not every area is a gray area, and part of the point of scholarship is to try to create a category of thought that is more careful and thorough than random opinion. It doesn’t always work, and it only does work when challenges to consensus opinion are accepted, but this is different from saying that the challenges should be put on the same level because they are challenges rather than because they have shown themselves to be valid.

We should study the arguments made by slaveholders to defend slavery, but we do not want professors who romanticize the Old South with easily disprovable myths and lies. I happen to think climate scientists should spend more time publicly refuting the arguments of climate change deniers, and reviewing their books, but that does not mean that I think climate change deniers should make up a greater fraction of university faculty. Here at Current Affairs, I encourage writers to engage with right-wing views, by reading conservative books, quoting them, and refuting them, but I do not publish right-wing writers, because I believe the things we publish ought to have intellectual merit. We should reject the notion of “intellectual diversity,” to the extent that this means “granting equal legitimacy to two political perspectives without regard for whether one is intellectually sound,” but we should also reject the idea that we can simply shun and ignore ignorant opinions. It’s important to study why people hold onto beliefs that are outdated or unfounded. It’s also important to recognize when people are pushing those outdated or unfounded beliefs not because they believe in “intellectual diversity,” but because they are attempting to push an agenda.

Conservatives like to portray the left as a sinister cabal of idealogues trying to replace the truth with their feelings through ideological indoctrination. In fact, that is a much better descriptor of the right’s attempt to control university education, to undercut the authority of teachers and professors and to teach the version of history that Republican state legislators prefer rather than the version historians themselves reach consensus on.

The concept of “intellectual diversity” is a clever one, in that it poses as something benign, when in fact it is a quite radical call to re-engineer the academy to include views that serious scholars overwhelmingly reject. Instead of intellectual diversity, we just need intellectual seriousness: it is perfectly fine not to have many right-wing professors, if there are clear refutations and responses to the right-wing positions in question that can justify the demographic gap. If right-wing ideas are exposed as discredited and flimsy, then they have no place in the academy. But to make that case, we have to do the work of discrediting them. They cannot be legitimized because they are widely held, but nor can we reject them simply because we dislike them.