Editor’s note: This work of fiction originally appeared in Issue 30 of the Current Affairs print edition.

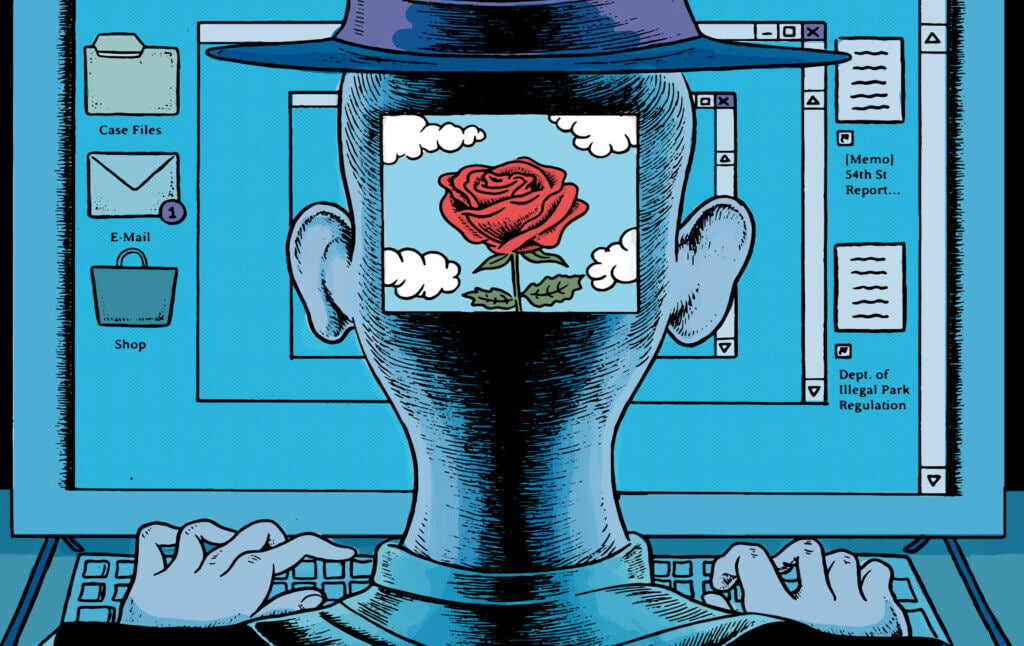

The 54th Street matter came to my attention by mistake. At the time, I had no inclination that it would lead to the ruination of my career; nor could I predict that this ruination would become, in turn, the triumph of my life. It began last July. I was sitting in my office at work, shopping online as usual, when a new email appeared in my inbox—but not just any email. This was a designation memo from the Bureau of Consumer Protection assigning a new case. For almost two years I had extensively assisted with cases—researching regulations, writing memos, and maintaining case files—but always as a junior employee; I had never been entrusted with a leading role. I was hungry for action, and so when I saw the new case arrive in my inbox, I determined to claim it for myself. No one was going to stop me.

And what a case it was! The memo detailed credible reports of an illegal installation on 54th Street between 30th and 31st Avenues. Apparently, there were flowers and plants all over the street and the sidewalk, obstructing pedestrians, parking and probably even traffic. All of it was completely unlicensed, and the relevant files showed no record of even a permit application! As I read the memo, I imagined the suffering of the industrious residents of 54th Street. These unlicensed plants could be carrying diseases! They could be invasive species! They could completely disrupt the aesthetic effect of the officially sanctioned foliage along the street, sowing discord and an explosion of speculative opinions, pitting resident against resident, turning the district against itself! This was exactly the type of intolerable situation I had signed up to fight against.

From an early age I knew my calling was to be a public servant. I have always loved the city and its profusion of life: cars everywhere roaring and honking, eagerly accelerating into the future; people rushing about on important business; vacant land developing into profitable stores and sleek new residences. How safe it felt to step into a new restaurant, past the happy green “A” in the window, knowing it had been inspected by a city official and achieved a superior score. Above all how invigorating it felt to leave all the concrete and noise behind in the city’s parks. Every tree and lawn and ramble was exactly where it should be, all according to plan. The city parks all got an “A” in my book. It was, therefore, completely natural that I wound up working to protect the integrity of the city’s parks at the Department of Illegal Park Removal.

I immediately forwarded the designation memo to my department head, a leading expert and pioneer in the field of illegal park removal, and requested to be put on the case. You can only imagine the restlessness I felt as I stared at my inbox awaiting his response. Fearing the worst, I prepared the appeal I would make by phone. “For two years I have studied and learned from you,” I would say. “I know the regulations by heart. I maintain the case files better than anyone. I’m ready. My success will be your legacy.” Yet no appeal was necessary, for the department head neither granted nor denied my request. Instead he pointed out a consequential detail that I, in my exuberant inexperience, had overlooked. “The case cannot be assigned to you,” he wrote, “because the case has not been designated to our department. The memo is addressed to the Department of Illegal Art Removal, not the Department of Illegal Park Removal, and therefore falls outside our jurisdiction. It was sent to our department by mistake. You should read more carefully in the future.”

“But clearly there is a more fundamental mistake here,” I thought, refusing to accept defeat. That’s the department’s unofficial motto—“refuse to accept defeat”—and we type it after our signature on every email. The email I sent in response is probably the greatest I will ever send. In it, I passionately pleaded not just my claim to the case, but the department’s claim, which had been usurped by this incorrect designation. “The installation on 54th Street is clearly an illegal park,” I argued, “not merely an illegal artwork, and the representatives of that department were completely ill-equipped to handle the botanical aspect of this removal, not to mention their inexperience enforcing the requisite regulations that pertain to this botanical aspect. And besides,” I added, “our department needs to protect itself from outside encroachment. Far be it from me to impugn the motives of a fellow civil servant, but it is inconceivable that the intake specialist at the Bureau of Consumer Protection could make such a basic jurisdictional error out of benign neglect. We must protect our turf.” I offered to pursue, through the appropriate bureau channels, correction of the jurisdictional error; I would fight to claim the case for our department.

“OK,” my department head replied. And so began what I now regard as the apotheosis of my short-lived bureaucratic career, a months-long campaign of strategic bombardment so indomitable, so overwhelming in the sheer quantity of written deployments, that Robert Moses himself, I imagined, was applauding from his grave. Several weeks after my initial email salvos, it was determined that a bona fide jurisdictional dispute existed between our departments, and the matter was docketed and scheduled for adjudication at the Office of Inter-Bureau Jurisdictional Dispute Resolution. Over the following months, I feverishly prepared the argument I would deliver at the hearing.

The core of my argument was obvious and straightforward: the aesthetic effect of any botanical installation is primarily derived from its materiality qua its botanicality, and therefore this aspect must predominate in any consideration as to whether the installation in question is primarily a park or primarily an artwork. This is particularly true where, as here, the botanical element is not merely an attendant feature of a larger non-botanical installation, but is the primary substance of the installation itself. These contentions are obviously unassailable, and only a fool would argue to the contrary. Yet I discerned in my case one glaring weakness, an argument I would be defenseless against if I did not carefully prepare a response.

The problem could be framed as a question: who made this installation, and why? If I could not answer this, and could not convince the adjudicator of this answer, my case was sure to collapse. For as we all know, whenever we do not know why something was made, we simply call it art, even if it is clearly an illegal park. I fretted over these issues for many sleepless nights. “The plants are merely performing their plantness as an incongruous juxtaposition with the concreteness of the street,” I imagined my unknown adversary arguing at the hearing. “Yes, the plants appear in the form of a park,” my adversary would continue, “but this appearance is itself a performance, a mimetic representation of the dialectical relationship between the park and the street. The installation is therefore clearly a work of art. In fact, it follows that the entire concept of an illegal park is, by definition, the concept of an illegal artwork. Therefore,” my adversary would conclude, “the Department of Illegal Park Removal should be closed, and its funding transferred to the Department of Illegal Art Removal.”

Who could gainsay such logic, fresh from the most advanced graduate schools of contemporary social theory? I began to realize that in my exuberance I had exposed my entire department, and with it my livelihood and my vocation, to annihilation. I desperately sought some plausible explanation for the installation’s provenance. But reason alone provided no answers. For in truth, I was mystified as to why anyone could possibly seek to install an illegal park in the street, particularly when there are perfectly good licensed parks nearby. I needed more information, and so I began an exhaustive program of online research, in which I cataloged every publicly known fact about the installation.

I determined the installation began sometime during the night of May 1st. The next day, May 2nd, the residents of 54th Street awoke to find their street radically changed. Overnight, someone, or some group of people, had removed all the cars parked on the street and replaced them with flatbed trailers, linked together so that the trailers formed an uninterrupted line on both sides of the street running the entire length of the block. Each trailer-bed held a giant rectangular planter full of soil several feet deep, from which grew a reckless profusion of illegal botanicality. There were plants of every known variety, and even plants whose names did not appear anywhere in the licensing manual—plants I would not name even if I could, out of moral principle. On each side of the street, the plants were reportedly arranged around a central dirt path that linked all the soil beds, so that an unsuspecting citizen could walk down the entire city block atop the illegal installation, using the dirt path instead of the concrete sidewalk.

Reports said neighborhood residents soon began using the path, completely unaware of the danger all around them. Even worse, it was reported that they found the path pleasant, and particularly enjoyed the little niches that appeared here and there where one could sit surrounded by flowers and chat with friends and neighbors. There was even a little fountain. And it was all free.

But that was only the beginning. Soon after the matter first came to my attention in July, it appeared that the people in the area had actually begun to voluntarily tend and maintain the plants—weeding, planting, trimming, and so on, so that the installation, which they called a garden, did not merely deteriorate with time, but actually grew. People passed more and more time there, and held meals and parties there, and invited people who walked down the path to join these meals and parties, even complete strangers! It was, indeed, a dire situation. The people were being led astray, ignorant of their peril, into the domain of illegality.

Then, sometime in mid-August, new reports emerged, reports contemporaneous to the events they described, indicating that people in the area had taken it upon themselves to block off the street completely, and were actively filling the street itself with soil, and planting more plants and trees in this soil, and they were connecting the two gardens on the parking lanes to make one continuous garden covering the entire block. They were even installing planter-boxes on the sides of the buildings. I read that in one apartment a jet began to shoot water out of an open window over the heads of the path-walkers into a fountain, thereby linking the garden with the adjoining buildings, and in fact inducing the buildings to become part of the illegal park.

How powerless I felt at that time, seeing this illegal park proliferate while my hearing date was still months away. It was too much. Jurisdiction be damned, I needed to obey the higher call of duty. I swore an oath to protect the citizens of our great city from illegal parks, and so I resolved that even if I could not yet remove the illegal park, I could at least warn the citizens of its dangers. What I could not yet achieve by force, I would accomplish through sweet persuasion.

I picked the date of my journey into the heart of darkness and made all the necessary preparations. I checked and rechecked my route, and planned a backup route in case of subway failure. I purchased new hiking boots and wore them all day at work for two weeks to break them in. I blended trail mix for nourishment. I prepared a stack of pamphlets containing the relevant city regulations for the enlightenment of the wayward citizens. On August 29th, I set out.

What I found defied all expectation.

Have you ever seen a beauty beyond words, one that evaporates all your preoccupations and anxieties, and you stand before it as if with a naked soul, transfixed? So I stood, upon turning the corner onto 54th Street, transfixed before a vision of city life I had never imagined possible, until a young couple promenading hand-in-hand along a nearby path turned to me with warm and gentle smiles, took me by the hand, and welcomed me to join them.

I cannot convey the convertive force of what I experienced that day, for my words are not a harmony of fragrant air, shining sunlight, green life, and joyous smiles—I cannot reach out of this page and enchant the room or subway car or café or park bench where you are reading. But, you can. Reader, if you seek but cannot find what I recount, you must imagine it for yourself, band with others, and make it in the world. I can say only what it inspired in me.

I felt a new spirit there, manifest flowering groves ringing with laughter and lively discussion, the shimmering fountains and colonnades of verdant young trees bursting into the sky, the vine-adorned facades of the enframing buildings, windows and doors flung open, wafting down the smell of delicious cooking – and everywhere people, radiating with beauty and vigor as they create a shared life together in the flourishing garden that surrounds them. With exuberant cheer, strangers and neighbors greet each other warmly. They meander beneath the shady colonnades, bask on stones warming in the sun, and picnic in secluded groves. They tend to young plants, coaxing forth green shoots and guiding each towards its rightful place in the harmonious whole. They delight in the play of birds. They gather bright stones and arrange them in pleasing patterns. They attend with light ears to the music of the fountains, add their own soft melodies, and dance with quick feet to songs of their own making. They discourse on the shapes of clouds and the meanings of dreams. They emerge from buildings carrying heaping platters of savory dishes, and feast together in abundant variety. And throughout all this, in each and every expiring breath they bequeath to the garden air, a breath they will never recover, the only breath they can take in that specific, unique, irrevocable moment in their short lives, they exalt with reverent pleasure the poetic artistry of their manifold shared creations. They invite all into their community who seek to join.

Later, I returned to the Department of Illegal Park Removal fairly bursting with momentous news. I went straight into the office of my department head and fumbled for words to describe what I had seen. In truth I failed, for I am no poet. He stared at me with a look of dawning contempt, then commanded me to silence and announced that the wonders of which I spoke cannot be real, and the only explanation is that I had succumbed to the intoxicating influence of art. “You should never have gone without permission,” he said, “particularly where the installation in question is potentially an illegal artwork, which you were clearly completely unprepared to encounter.” He concluded that the department would renounce its jurisdictional claim. I asked him once to go with me, to see the garden with his own eyes. He refused, and banned me from returning to the garden. I quit.

Now I pass my days in the garden. We tend it together, and tend to each other. When I first arrived, I did not know the name for what I saw, but now I know. Here, at last, I have found the reconciliation of humanity and nature, the discovery and joyous expression of our spirit in the harmonious cultivation of nature, and through this cultivation the rediscovery that we are, and always have been, of nature. A god lives here, a god we have made, a god that lives in us and our creation: the god of 54th Street.

One day, I fear, they will come to kill our god, and we will defend the garden. Yet even if they destroy the garden, they cannot destroy our god, for the spirit lives in us, and we shall plant new seeds everywhere.